Conversion Surgery in Advanced Unresectable Gastric Cancer After Induction Fluorouracil Plus Leucovorin, Oxaliplatin, and Docetaxel

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Hong Kong J Radiol 2025;28:Epub 5 March 2025

Conversion Surgery in Advanced Unresectable Gastric Cancer After Induction Fluorouracil Plus Leucovorin, Oxaliplatin, and Docetaxel

R Liu1, HLY Hou1, RPY Tse1, KK Yuen1, DLW Kwong2, WL Chan2

1 Department of Clinical Oncology, Queen Mary Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

2 Department of Clinical Oncology, Li Ka Shing Faculty of Medicine, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

Correspondence: Dr R Liu, Department of Clinical Oncology, Queen Mary Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China. Email: lr638@ha.org.hk

Submitted: 15 August 2024; Accepted: 27 November 2024. This version may differ from the final version when published in an issue.

Contributors: RL and WLC designed the study. RL acquired the data. RL and HLYH analysed the data. RL drafted the manuscript. All authors critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of Interest: As an editor of the journal, DLWK was not involved in the peer review process. Other authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Funding/Support: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data Availability: All data generated or analysed during the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: This research was approved by the Institutional Review Board of The University of Hong Kong/Hospital Authority Hong Kong West Cluster, Hong Kong (Ref No.: UW24-514). The requirement for patient consent was waived by the Committee due to the retrospective nature of the research.

Abstract

Introduction

Palliative chemotherapy is the standard treatment for unresectable locally advanced gastric cancer (GC) with poor prognosis. We evaluated the safety and efficacy of a multimodality approach with induction fluorouracil plus leucovorin, oxaliplatin, and docetaxel (FLOT) followed by attempted conversion surgery with additional FLOT at a tertiary hospital in Hong Kong.

Methods

Medical records of advanced GC patients treated with induction FLOT and attempted conversion surgery between 2017 and 2023 were reviewed. Patients suitable for surgery after chemotherapy underwent resection, followed by adjuvant FLOT for another four cycles. Safety, treatment outcomes and predictive factors for survival were analysed.

Results

Thirty-one patients (25 males, median age = 63 years) were included. The median follow-up time was 22.0 months. Disease control rate after induction FLOT was 87.1% (n = 27). Conversion surgery was performed in 23 patients (74.2%), with 20 achieving R0 resection. Patients with conversion surgery had longer median overall survival (OS) and event-free survival than those who could not undergo surgery. Multivariable analysis identified no conversion surgery, higher neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio, serum albumin level <35 g/L, body mass index <23 kg/m2, and clinical nodal stage N3 disease with a worse OS. No treatment-related deaths occurred. The incidence of grade ≥3 toxicities was 51.6%, with neutropenia (29.0%) and febrile neutropenia (12.9%) being most common.

Conclusion

Induction FLOT achieved high conversion rates and R0 resections, offering a favourable survival benefit and acceptable safety in unresectable GC. Prospective trials incorporating biomarker-driven therapy may further improve pathological complete response rates and survival.

Key Words: Adenocarcinoma; Induction chemotherapy; Stomach neoplasms

中文摘要

晚期不可切除胃癌在接受誘導氟尿嘧啶、亞葉酸鈣、奧沙利鉑及多西他賽治療後的轉化手術

廖文傑、侯力予、謝佩楹、袁國強、鄺麗雲、陳穎樂

引言

緩和性化療是預後差的不可切除局部晚期胃癌的標準治療。患者在接受誘導氟尿嘧啶、亞葉酸鈣、奧沙利鉑及多西他賽(FLOT)治療後嘗試進行轉化手術再配合FLOT是一個多模態治療方式,我們評估這治療方式在香港某所三級醫院的安全性及效用。

方法

我們對在2017至2023年間接受誘導FLOT及嘗試轉化手術治療的晚期胃癌患者的醫療紀錄進行回顧性研究。適合在化療後進行手術的患者接受切除,然後進行另外四個療程的輔助FLOT治療。我們分析了安全性、治療結果及存活的預測因素。

結果

本研究包括31名患者(25名男性,年齡中位數 = 63歲)。隨訪時間中位數為22.0個月。在接受誘導FLOT治療後的疾病控制率為87.1%(n = 27)。共有23名患者(74.2%)接受了轉化手術,當中20名達至完全切除(R0)。與不能接受手術的患者相比,接受了轉化手術的患者的整體存活時間及無事件存活時間均較長。多變量分析識別出沒有接受轉化手術、嗜中性白血球與淋巴球比例(NLR)較高、血清白蛋白水平<35 g/L、體重指標(BMI)<23 kg/m2及臨床第N3期胃癌的整體存活較差。本研究沒有發生與治療相關的死亡事件。毒性≥3的發生率為51.6%,當中以嗜中性白血球減少症(29.0%)及嗜中性白血球減少症合併發熱(12.9%)最為常見。

結論

誘導FLOT治療達至高轉化率及完全切除,為不可切除胃癌患者提供了有利的存活獲益及可接受的安全性。結合生物標記驅動治療的前瞻性試驗可進一步改善病理完全緩解率及存活。

INTRODUCTION

Gastric cancer (GC) is the sixth most common cancer

and the sixth leading cause of cancer deaths in Hong

Kong.[1] Worldwide, it is the fourth most common leading

cause of cancer deaths (7.7%).[2] While surgical resection

is the treatment of choice for operable GC, many patients

eventually relapse. Thus, combined modality treatment is

recommended for resectable GC classified as stage ≥IB

disease under the TNM (Tumour, Node and Metastasis)

system.[3] [4] Unresectable locally advanced/metastatic GC

has a poor prognosis with a median overall survival

(OS) of about 4 to 6 months with supportive care alone.[5]

With the use of various combination chemotherapeutic

regimens containing platinum, fluoropyrimidine, taxane,

irinotecan, and/or trastuzumab, the median survival time

improves to approximately 11 to 15 months.[5] [6] [7] [8] [9] [10] Recently,

the addition of immunotherapy to chemotherapy has

also been shown to improve survival in the first-line

advanced/metastatic setting, especially for those with

high expression of programmed death ligand 1.[11] [12]

Currently, the standard of care is palliative in nature, and newer multidisciplinary therapeutic approaches to

improve survival and offer a chance of cure for advanced

GC are being evaluated.

The role of surgery in advanced GC is a controversial

topic. Advanced GC is a heterogeneous disease with

varying extents of local invasion, varying locations and

extent of lymph node metastases, and diverse metastatic

patterns. The REGATTA randomised phase three trial

(Reductive Gastrectomy for Advanced Tumour in Three

Asian Countries)[13] failed to show a survival advantage

with gastrectomy followed by chemotherapy versus

chemotherapy alone in advanced GC. This could partly

be explained by the decreased tolerance to chemotherapy

after gastrectomy, which was similarly shown in the

perioperative setting in the MAGIC trial.[14] Conversion

surgery, in which patients with unresectable tumours

are given neoadjuvant chemotherapy in an attempt to

downstage the disease and achieve an R0 resection,

is an appealing approach in advanced GC.[15] Besides

downstaging the tumour itself, the rationale behind giving neoadjuvant chemotherapy is to eradicate occult

metastatic disease and to take advantage of the improved

tolerance of chemotherapy compared to the postoperative

setting. Most data on conversion therapy are from

single-arm phase two studies and retrospective cohort

studies.[16] [17] [18] [19] [20] [21] [22] [23] [24] Various neoadjuvant chemotherapy regimens

including docetaxel, capecitabine/S-1, and cisplatin/oxaliplatin, have been used as conversion therapy in

treating advanced GCs.[16] [17] [18] [19] [20] [21] [22] [23] [24] The median survival time

of patients following R0 resection is up to 41 to 57

months,[16] [18] [19] [23] dramatically better than that achieved

by palliative systemic treatment alone. Perioperative

chemotherapy regimens such as S-1 plus cisplatin, and

fluorouracil plus leucovorin, oxaliplatin, and docetaxel

(FLOT) have also been used in conversion therapy and

demonstrated favourable outcomes, especially in those

with limited metastatic advanced GC.[25] [26]

The multidisciplinary approach of using induction FLOT

for four cycles followed by attempted conversion surgery

for advanced GC has been used in our centre since 2017.

Our centre prefers to use FLOT due to our experience

with it in the perioperative setting for resectable GC.

Perioperative FLOT in resectable GC has been shown to

have a high pathological response rate with a reasonable

toxicity profile[27] [28] and is the preferred regimen in this

setting as recommended by the National Comprehensive

Cancer Network[4] and the European Society for Medical

Oncology.[3] This retrospective study evaluated the safety

and efficacy of incorporating FLOT and conversion

surgery in advanced GC.

METHODS

Patients

The cases of 31 consecutive patients with clinically

unresectable, locoregionally advanced GC (cT2-4bN0-3M0) treated with induction FLOT with the goal of

conversion surgery at Queen Mary Hospital, Hong

Kong between January 2017 and December 2023

were reviewed. All patients had undergone baseline

upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, were diagnosed with

histologically confirmed gastric or gastroesophageal

junction adenocarcinoma, and had received staging

18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography–computed tomography (18F-FDG PET/CT) whole-body

scans. Disease was staged according to the 7th and 8th

TNM staging system developed by the American Joint

Committee on Cancer.[29] [30] [31] Preoperative exploratory

laparoscopy to rule out peritoneal metastases was

not mandatory. All cases were deemed clinically

unresectable with locoregionally advanced disease after discussion in multidisciplinary meetings comprising

of surgeons, oncologists, and radiologists. Hitherto

‘unresectable’ features included invasion into adjacent

organs (clinical tumour stage T4b [stage cT4b] disease),

locoregionally advanced/bulky non–stage cT4b disease,

or extensive involvement of regional lymph nodes.

These groups of patients were targeted as they would

otherwise receive palliative systemic treatment. Patients

with grossly definite metastases (i.e., visible on 18F-FDG

PET/CT or histologically confirmed at surgery) or

distant metastases to visceral organs other than lymph

nodes were not included, as our centre would treat these

patients with multimodality treatment consisting of

intraperitoneal chemotherapy or systemic therapy with

palliative intent.

Treatment Overview

All patients received induction chemotherapy using

FLOT according to the protocol used in the FLOT4 trial.[28]

Each cycle of FLOT consisted of intravenous docetaxel

50 mg/m2, oxaliplatin 85 mg/m2, and leucovorin

200 mg/m2, followed by a 24-hour continuous infusion

of fluorouracil 2600 mg/m2 on day 1. This regimen

was given every 2 weeks for four cycles. The dose

was adjusted if patient had intolerable side-effects.

Prophylactic use of granulocyte colony-stimulating

factor (G-CSF) was used as needed.

Evaluation of Response

Clinical response was assessed after four cycles of

FLOT with upper gastrointestinal endoscopy and

18F-FDG PET/CT scan. Response measurement was

classified according to RECIST (Response Evaluation

Criteria in Solid Tumors) version 1.1.[32] All cases were

re-evaluated in multidisciplinary meetings. If the tumour

responded well and curative resection was judged

to be possible, conversion surgery was scheduled.

Patients with tumours that responded unsatisfactorily

and were unlikely amenable to curative resection were

administered palliative second-line treatments.

Conversion Surgery and Follow-up

All patients included were alive within 10 weeks from the

day of last administration of FLOT. Conversion surgery

was performed within 10 weeks from the day of last

FLOT. If surgical exploration did not reveal unresectable

features, R0 resection was attempted. Depending on

the location and size of the gastric or gastroesophageal

junction tumour, curative resection involved distal or

total gastrectomy plus or minus oesophagectomy, along

with D2 lymph node dissection. After surgery, another four cycles of adjuvant FLOT were administered to those

with R0 resection. For patients with R1 or R2 resections,

subsequent treatments were chosen at the discretion of

oncologists.

For patients who underwent conversion surgery and

completed adjuvant FLOT, the follow-up schedule

consisted of clinical visits at least once every 3 months

during the first 2 years, followed by at least once every 6

months. CT or 18F-FDG PET/CT was performed at least

once every 6 months for the first 3 years.

Outcome Measures and Statistical Analyses

Relevant clinical and pathological parameters were

recorded from clinical notes and the Clinical Management

System of the Hospital Authority. These data included

age, sex, body mass index (BMI), co-morbidities,

baseline blood tests, tumour characteristics, clinical

response, pathological response using the Modified Ryan

score,[33] and any adverse events from chemotherapy.

All statistical analyses were conducted using R version

4.3.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing).

Treatment outcomes included OS, defined as the period

from the time of starting induction FLOT to the date of

death or the last follow-up time; and event-free survival

(EFS), defined as the period from the time of starting

induction FLOT to the date of disease progression,

relapse, death or the last follow-up time. Safety was

evaluated according to the National Cancer Institute’s

CTCAE (Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse

Events) version 5.0.[34] OS and EFS of the groups

with and without conversion surgery were analysed

using the Kaplan-Meier method. The differences in

survival time were investigated by the log-rank test.

Simple and multivariable Cox proportional hazards

regression analyses were performed to identify clinical

and pathological variables in relation to survival. Each

clinical and pathological variable was assessed

individually using simple Cox regression and Kaplan-Meier curves with log-rank tests. Significant clinical

and pathological variables with p value ≤ 0.1 in

simple analysis were incorporated into a multivariable

regression model. Multivariable Cox regression model

was used to evaluate the independent effect of each factor

while adjusting for other variables. Hazard ratios were

presented with 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs). A

two-sided p value < 0.05 was considered as statistically

significant.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

During the study period, 31 patients (25 males and

6 females) with recently diagnosed locoregionally

advanced and clinically unresectable GC received

FLOT. The median age was 63 years (range, 34-80).

All patients had an Eastern Cooperative Oncology

Group performance status score of ≤2, with majority

(93.5%) scoring 1. Fourteen patients (45.2%) had

baseline anaemia requiring blood transfusion and seven

patients (22.6%) required either feeding tube insertion or

gastrojejunostomy for dysphagia. In total, two patients

(6.5%) had stage cT3 disease, 16 (51.6%) had stage

cT4a disease and 12 (38.7%) had stage cT4b disease.

Eight patients (25.8%) had clinical nodal stage N1 (stage

cN1) disease, 14 (45.2%) had stage cN2 disease and six

(19.4%) had stage cN3 disease. As stated above, reasons

for unresectability included invasion into adjacent organs

(stage T4b disease) in 12 patients (38.7%) [pancreas,

n = 6; liver, n = 3; colon, n = 3; heart, n = 1; spleen, n = 1],

locoregionally advanced/bulky non–stage cT4b disease

in 15 patients (48.4%), and extensive regional lymph

node involvement in 13 patients (41.9%). Seven patients

(22.6%) had two unresectable features and one (3.2%)

had three unresectable features. Table 1 summarises

the baseline characteristics of this study cohort. The

median follow-up time was 22.0 months (range, 5.8-

80.7). During the follow-up period, 19 (61.3%) of the 31

patients died.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of patients who had induction fluorouracil plus leucovorin, oxaliplatin, and docetaxel (n = 31).

Clinical and Pathological Response and

Adverse Events

All patients except one (96.8%) completed the intended

four cycles of induction FLOT, with one patient

developing grade 3 encephalopathy and only received

three cycles. The disease control rate after induction

FLOT was 87.1% (n = 27), of which 23 patients (85.2%)

had a complete response (CR) or partial response (PR)

and four patients (14.8%) had stable disease (SD) on

imaging. Conversion surgery was performed in 23

patients (74.2%), with 20 underwent R0 resections, two

underwent R1 resections (microscopic distal duodenal

margin), and one underwent R2 resection (macroscopic

lymph nodes encasing major arteries). Total gastrectomy

was performed in seven patients (22.6%), distal

gastrectomy in nine (29.0%), and oesophagogastrectomy

in seven patients (22.6%). The median time between

end of chemotherapy and surgery was 5.4 weeks

(interquartile range, 3.8-6.8). Patients not undergoing conversion surgery included eight (25.8%) with stable

disease with unresolved unresectable features (n = 5)

and progressive disease (n = 3). Of these eight patients,

one underwent a palliative gastrojejunostomy and one a

palliative oesophagogastrectomy.

The pathological response rate was 60.9%, of which

two patients (8.7%) had pathological complete response

(pCR) or near complete response. All patients with

pathological response had radiological PR. Amongst

those with poor pathological response, seven had

radiological PR, one had radiological SD, and one had

radiological progressive disease.

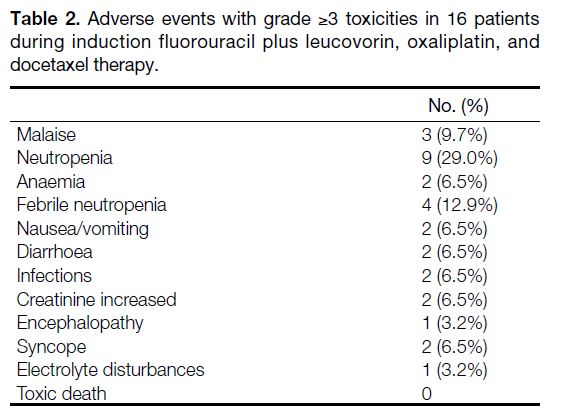

During preoperative FLOT, 20 patients (64.5%) received

prophylactic G-CSF support. The incidence of grade 3 or

4 toxicities during FLOT was 51.6%. Neutropenia (n = 9,

29.0%) and febrile neutropenia (n = 4, 12.9%) were the

most common; nine of these occurred in those without

prophylactic G-CSF. Non-haematologic adverse events

of grade ≥3 toxicities were not common in this cohort,

with malaise being the most common (9.7%). Treatment

was generally well tolerated, and no treatment-related deaths occurred. Table 2 shows adverse events with

grade ≥3 toxicities on FLOT.

Table 2. Adverse events with grade ≥3 toxicities in 16 patients during induction fluorouracil plus leucovorin, oxaliplatin, and docetaxel therapy.

Post Surgery

Postoperative complications were infrequent and

occurred in four patients (17.4%). They included

pneumonia, arrythmia, surgical emphysema, and

surgical site infections. No patients died within 30 days

after surgery.

Among 20 patients who underwent successful R0

conversion surgery, 19 (95.0%) started postoperative FLOT, with only one (5.3%) not completing the

intended four cycles due to malaise. One patient (5.0%)

in the R0 resection group did not start postoperative

FLOT and received TS-1 and cisplatin instead because

of the appearance of new perigastric lymph nodes while

on preoperative FLOT, though conversion surgery

was still deemed feasible. One of two patients with

R1 resection had a postoperative course of TS-1 and

chemoradiotherapy with TS-1 to the operative bed, while

the other one continued on FLOT. The patient with R2

resection continued on TS-1 alone.

Of the eight patients who did not undergo conversion

surgery, seven continued on chemotherapy (two receiving

FLOT, and one each receiving irinotecan/ramucirumab,

paclitaxel/ramucirumab, cisplatin/capecitabine/trastuzumab, TS-1/cisplatin, and capecitabine/oxaliplatin/pembrolizumab). The other patient received

palliative radiation therapy and best supportive care.

Survival

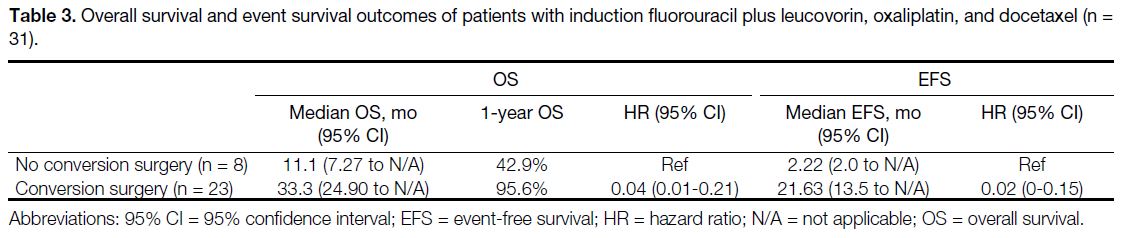

For the entire cohort of 31 patients, the median OS was

26.3 months (95% CI = 18.4 to not applicable) and median

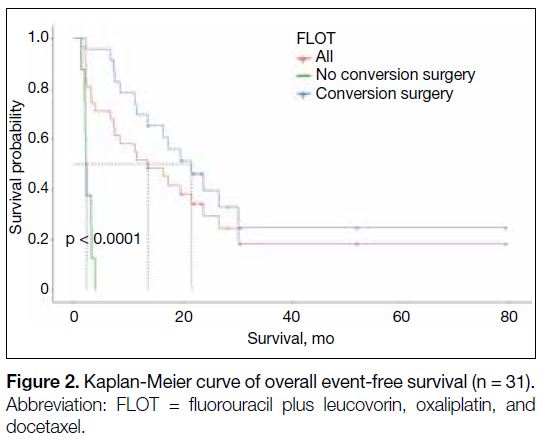

EFS was 13.5 months (95% CI = 7.3-26.7). Patients

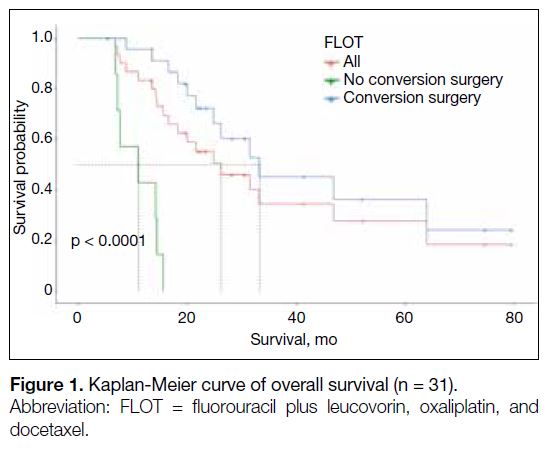

undergoing conversion surgery had a longer median OS

(median OS = 33.3 months vs. 11.1 months) [Table 3 and Figure 1] and EFS (median EFS = 21.63 months vs.

2.22 months) [Table 3 and Figure 2] than those who did not. The 1-year survival proportion was also higher in

patients with conversion surgery versus those without

(95.6% vs. 42.9%) [Table 3 and Figure 1]. Multivariable

analysis showed that low BMI, higher neutrophil-to-lymphocyte

ratio (NLR), low serum albumin level, stage

cN3 disease, and those without conversion surgery were

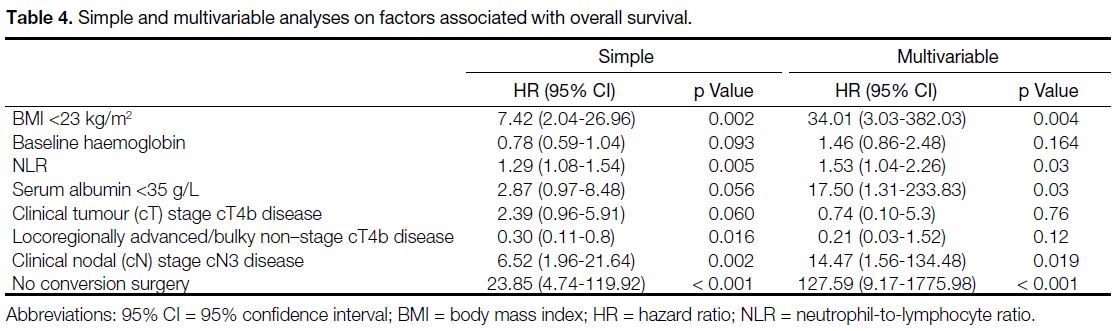

associated with worse OS (Table 4).

Table 3. Overall survival and event survival outcomes of patients with induction fluorouracil plus leucovorin, oxaliplatin, and docetaxel (n = 31).

Figure 1. Kaplan-Meier curve of overall survival (n = 31).

Figure 2. Kaplan-Meier curve of overall event-free survival (n = 31).

Table 4. Simple and multivariable analyses on factors associated with overall survival.

Pattern of Recurrence

Among 20 patients who underwent R0 conversion

surgery, 12 developed recurrences. Peritoneum was

the most common site of first relapse (n = 7), followed

by distant lymph nodes (n = 6) and liver (n = 3). Eight

patients went on to have active palliative systemic

treatment while four had palliative radiotherapy and best

supportive care.

DISCUSSION

This retrospective study demonstrated the high efficacy

of induction FLOT and subsequent conversion surgery

in unresectable advanced GC, offering a chance of cure

with long-term survival benefit with acceptable safety in

a hitherto palliative scenario.

Induction FLOT led to a high response rate with disease

control rate of 87.1% (85.2% CR/PR and 14.8% SD).

No patient died within 10 weeks of last induction

FLOT, and it achieved a high conversion rate of 74.2%.

Among the 23 patients who underwent conversion

surgery, 87.0% (n = 20) achieved R0 resection. These

appeared to be slightly better figures compared with the

AIO-FLOT3 trial (Arbeitsgemeinschaft Internistische

Onkologie-fluorouracil, leucovorin, oxaliplatin, and

docetaxel) done in Germany,[26] which reported a response

rate of 43% to 60% in patients not upfront resectable, and

a 60% conversion rate and 80.6% R0 resection in arm B

(patients with limited metastases). It is understandable

because our study focused on patients with relatively

less advanced stages compared to the AIO-FLOT3 trial

while the AIO-FLOT3 trial recruited stage IV patients

with more distant metastases.[26] Nevertheless, these are

encouraging results as it confirms that a majority of

patients may be able to have conversion surgery done

with upfront unresectable advanced GC, especially for

those with less bulky disease and metastatic burden. The

high R0 resection rate in our study is important because

R0 resection offers the best chance of cure in GC and

is a prognostic factor for survival for patients after

preoperative chemotherapy.[25] [35] [36] Patients with non-R0

tumour resection have a poor prognosis and non-R0

resection should be avoided in advanced GC.[37] [38]

Our study showed that induction FLOT was well

tolerated. All patients except one completed four cycles

of induction FLOT. For those with R0 conversion surgery

and planned postoperative FLOT, 95.0% completed

four cycles. The high postoperative chemotherapy

compliance rate is an important finding in this study as

previous trials have reported low compliance with other

postoperative chemotherapy regimens due to toxicity

after gastrectomy.[14] [39] [40] The REGATTA trial[13] did not

show a survival advantage with gastrectomy followed by

chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone in advanced

GC, underscoring the importance and better tolerability

of induction chemotherapy. The incidence of grade 3 or

4 toxicities during FLOT was comparable to those in the

perioperative setting in resectable GCs.[28]

The FLOT4 trial[28] established perioperative FLOT as

standard of care in locally advanced resectable GC.

However, the role of perioperative chemotherapy in

unresectable advanced GC such as the ones reviewed

in this study is uncertain. Conversion therapy for GC is

a multimodality strategy garnering attention in recent

years.[15] However, definition of conversion therapy varies

widely, and studies have included different induction

chemotherapy regimens, surgical resection types, and

local and metastatic status. A systemic review and meta-analysis[41]

found that induction chemotherapy followed

by conversion surgery led to survival advantage when

compared with chemotherapy alone for advanced

GC. However, it also concluded that most patients in

the surgery group had only one non-curative clinical

factors versus more in the non-surgery group.[41] Those

in the surgery group were more often chemotherapy

responders and most patients underwent R0 resection.[41]

The CONVO-GC-1 study (International Retrospective

Cohort Study of Conversion Therapy for Stage IV

Gastric Cancer 1)[16] suggested that conversion therapy

is a promising approach even for those with stage IV

disease involving multiple sites and organs, given that

they have a response to chemotherapy and R0 resection

can be achieved. Likewise, the AIO-FLOT3 trial[26]

demonstrated improved survival in patients with limited

metastatic disease.

This study achieved quite a remarkable OS for those

patients undergoing conversion surgery after induction

FLOT. With this multimodality approach, patients

with conversion surgery had tripled the median OS of

33.3 months compared to 11.1 months in those without

conversion surgery. The hazard ratios of 0.04 in OS

and 0.02 in EFS are remarkable. A total of 95.6% of

patients undergoing conversion surgery survived the

1-year mark, more than double that of those who did

not undergo conversion surgery (42.9%). Patients who

did not undergo conversion surgery essentially had

survival time similar to that quoted in the literature for

advanced GC (11-15 months).[5] [6] [7] [8] [9] [10] The longer survival

for those who underwent conversion surgery may not

be fully attributable to the surgery itself. It can also

be a reflection of biological behaviour of the tumour:

patients with chemotherapy-sensitive tumours have

better survival than those with relatively chemotherapyresistant

tumours.

Several studies, mainly conducted in Japan, had reported

a wide range of median OS from 13 to 48 months with

induction chemotherapy followed by conversion surgery approach.[16] [19] [20] [24] [25] [26] Most of these studies were done on

stage IV advanced GC.[16] [20] [24] [25] [26] Factors associated with

longer survival times included negative para-aortic

lymph nodes,[20] R0 resection,[20] [24] [25] positive peritoneal cytology as the only non-curative factor,[25] downstaging,

pathological response,[24] and those with only

retroperitoneal lymph node metastases.[26] Our study

found that low BMI (<23 kg/m2), higher NLR, low serum

albumin level (<35 g/L), stage cN3 disease, and those

without conversion surgery were associated with worse

OS (Table 4). Most of these factors can be identified

at baseline and help with clinical decision making.

Hypoalbuminaemia was similarly found to be predictive

of worse outcomes in a retrospective study looking at

patients receiving CROSS (neoadjuvant carboplatin and

paclitaxel with radiotherapy) or FLOT in advanced GC.[42]

In the same study, low BMI was not associated with

survival.[42] Another study showed that BMI is predictive

of survival outcomes in gastroesophageal cancers.[43] This

inconsistent finding of BMI as a prognostic factor is

likely due to the fact that it may not be a perfect marker

for nutrition or that nutrition plays only a small role

in affecting survival. NLR is a known blood marker

representative of systemic inflammation response, which

influences tumour progression.[44] It has been shown to be

a prognostic marker in predicting tumour progression

for resectable GC.[45] Similarly, our study confirms higher

NLR was associated with worse OS.

One unique aspect of our study is that it focused

mostly on unresectable advanced GC with advanced

local tumour and nodal staging, with almost 40% stage

cT4b disease, and almost half with locoregionally

bulky non–stage cT4b or extensive regional lymph

node metastases. On the other hand, a lot of the studies

quoted previously in conversion therapy investigated

stage IV advanced GC as a whole, consisting of a lot

more patients with distant metastases.[1] [16] [17] [20] [21] [23] [24] [25] [26] The

absence of laparoscopic staging might have resulted

in inclusion of more upstaged patients with potentially

positive peritoneal cytology or small peritoneal implants,

which confer a worse prognosis. Given this limitation,

the median OS achieved in our study was still admirable.

In recent years, efforts to improve outcomes of resectable

GCs investigated the addition of immune checkpoint

inhibitor to perioperative FLOT. Data from both the

KEYNOTE-585[46] and MATTHERHORN trials[47]

demonstrated an increase in pCRs of about 10% with the

addition of pembrolizumab and durvalumab, respectively.

Our pCR rate of 8.7% is consistent with the FLOT-only arm of these two studies.[46] [47] Our study showed that poor

pathological response had a trend of worse survival.

Whether pCR translates to longer survival in advanced

GC remains controversial as compared to other tumour

types (e.g., triple-negative breast cancer or lung cancer)

where pCR is a surrogate for survival. The addition of

pembrolizumab showed favourable outcomes in EFS but

no difference in OS so far.[48] The MATTERHORN trial[47]

is still awaiting long-term results.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, it is a single-centre retrospective analysis and there was no control

group for comparison. Second, the sample size is small.

Third, quality-of-life of the patients and cost-effectiveness

were not measured. Taken all together, induction FLOT

followed by conversion surgery should be strongly

considered if patient has limited burden of baseline

incurable factors which responded to chemotherapy and

R0 resection is anticipated, as this offers a favourable

survival benefit for patients with advanced GC.

CONCLUSION

Our study showed that induction FLOT achieved

high conversion rates and R0 resections, providing

a favourable survival benefit with acceptable safety

in unresectable GC. Future research is warranted to

explore whether adding immune checkpoint inhibitors,

especially for patients with high programmed death

ligand 1 expression, or other more effective biomarkerdriven

therapy can further improve the conversion rate,

pCR rate, and survival.

REFERENCES

1. Centre for Health Protection, Department of Health, Hong Kong

SAR Government. Stomach cancer. 2024 Jan 12. Available from:

https://www.chp.gov.hk/en/healthtopics/content/25/55.html. Accessed 22 May 2024.

2. Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I,

Jemal A, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN

estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in

185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71:209-49. Crossref

3. Lordick F, Carneiro F, Cascinu S, Fleitas T, Haustermans K, Piessen G, et al. Gastric cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2022;33:1005-20. Crossref

4. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Guidelines for

Gastric Cancer Version 2.2024. Available from: https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/guidelines-detail?category=1&id=1434. Accessed 29 Jul 2024.

5. Wagner AD, Syn NL, Moehler M, Grothe W, Yong WP, Tai BC, et al. Chemotherapy for advanced gastric cancer. Cochrane

Database Syst Rev. 2017;8:CD004064. Crossref

6. Enzinger PC, Burtness BA, Niedzwiecki D, Ye X, Douglas K, Ilson DH, et al. CALGB 80403 (Alliance)/E1206: a randomized phase II study of three chemotherapy regimens plus cetuximab in

metastatic esophageal and gastroesophageal junction cancers. J

Clin Oncol. 2016;34:2736-42. Crossref

7. Koizumi W, Narahara H, Hara T, Takagane A, Akiya T, Takagi M, et al. S-1 plus cisplatin versus S-1 alone for first-line treatment of advanced gastric cancer (SPIRITS trial): a phase III trial. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9:215-21. Crossref

8. Bang YJ, Van Cutsem E, Feyereislova A, Chung HC, Shen L,

Sawaki A, et al. Trastuzumab in combination with chemotherapy

versus chemotherapy alone for treatment of HER2-positive

advanced gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction cancer (ToGA):

a phase 3, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet.

2010;376:687-97. Crossref

9. Park H, Jin RU, Wang-Gillam A, Suresh R, Rigden C, Amin M, et al. FOLFIRINOX for the treatment of advanced gastroesophageal cancers: a phase 2 nonrandomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2020;6:1231-40. Crossref

10. Van Cutsem E, Boni C, Tabernero J, Massuti B, Middleton G,

Dane F, et al. Docetaxel plus oxaliplatin with or without fluorouracil

or capecitabine in metastatic or locally recurrent gastric cancer: a

randomized phase II study. Ann Oncol. 2015;26:149-56. Crossref

11. Janjigian YY, Ajani JA, Moehler M, Shen L, Garrido M, Gallardo C,

et al. First-line nivolumab plus chemotherapy for advanced gastric,

gastroesophageal junction, and esophageal adenocarcinoma: 3-year

follow-up of the phase III CheckMate 649 trial. J Clin Oncol.

2024;42:2012-20. Crossref

12. Rha SY, Oh DY, Yañez P, Bai Y, Ryu MH, Lee J, et al.

Pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy versus placebo plus

chemotherapy for HER2-negative advanced gastric cancer

(KEYNOTE-859): a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, phase

3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2023;24:1181-95. Crossref

13. Fujitani K, Yang HK, Mizusawa J, Kim YW, Terashima M,

Han SU, et al. Gastrectomy plus chemotherapy versus chemotherapy

alone for advanced gastric cancer with a single non-curable factor

(REGATTA): a phase 3, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol.

2016;17:309-18. Crossref

14. Cunningham D, Allum WH, Stenning SP, Thompson JN, Van de

Velde CJ, Nicolson M, et al. Perioperative chemotherapy versus

surgery alone for resectable gastroesophageal cancer. N Engl J

Med. 2006;355:11-20. Crossref

15. Yoshida K, Yamaguchi K, Okumura N, Tanahashi T, Kodera Y. Is

conversion therapy possible in stage IV gastric cancer: the proposal

of new biological categories of classification. Gastric Cancer.

2016;19:329-38. Crossref

16. Yoshida K, Yasufuku I, Terashima M, Young Rha S, Moon Bae J,

Li G, et al. International retrospective cohort study of conversion

therapy for stage IV gastric cancer 1 (CONVO-GC-1). Ann

Gastroenterol Surg. 2021;6:227-40. Crossref

17. Kano Y, Ichikawa H, Hanyu T, Muneoka Y, Ishikawa T,

Ishikawa T, et al. Conversion surgery for stage IV gastric cancer:

a multicenter retrospective study. BMC Surg. 2022;22:428. Crossref

18. Sym SJ, Chang HM, Ryu MH, Lee JL, Kim TW, Yook JH, et al.

Neoadjuvant docetaxel, capecitabine and cisplatin (DXP) in patients

with unresectable locally advanced or metastatic gastric cancer.

Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:1024-32. Crossref

19. Inoue K, Nakane Y, Kogire M, Fujitani K, Kimura Y, Imamura H,

et al. Phase II trial of preoperative S-1 plus cisplatin followed by

surgery for initially unresectable locally advanced gastric cancer.

Eur J Surg Oncol. 2012;38:143-9. Crossref

20. Saito M, Kiyozaki H, Takata O, Suzuki K, Rikiyama T. Treatment

of stage IV gastric cancer with induction chemotherapy using S-1

and cisplatin followed by curative resection in selected patients.

World J Surg Oncol. 2014;12:406. Crossref

21. Kinoshita J, Fushida S, Tsukada T, Oyama K, Okamoto K,

Makino I, et al. Efficacy of conversion gastrectomy following

docetaxel, cisplatin, and S-1 therapy in potentially resectable stage

IV gastric cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2015;41:1354-60. Crossref

22. Mitsui Y, Sato Y, Miyamoto H, Fujino Y, Takaoka T, Miyoshi J,

et al. Trastuzumab in combination with docetaxel/cisplatin/S-1

(DCS) for patients with HER2-positive metastatic gastric cancer:

feasibility and preliminary efficacy. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol.

2015;76:375-82. Crossref

23. Yamaguchi K, Yoshida K, Tanahashi T, Takahashi T, Matsuhashi N,

Tanaka Y, et al. The long-term survival of stage IV gastric cancer

patients with conversion therapy. Gastric Cancer. 2018;21:315-23. Crossref

24. Sato Y, Ohnuma H, Nobuoka T, Hirakawa M, Sagawa T,

Fujikawa K, et al. Conversion therapy for inoperable advanced

gastric cancer patients by docetaxel, cisplatin, and S-1 (DCS)

chemotherapy: a multi-institutional retrospective study. Gastric

Cancer. 2017;20:517-26. Crossref

25. Satoh S, Okabe H, Teramukai S, Hasegawa S, Ozaki N, Ueda S, et al.

Phase II trial of combined treatment consisting of preoperative S-1

plus cisplatin followed by gastrectomy and postoperative S-1 for

stage IV gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2012;15:61-9. Crossref

26. Al-Batran SE, Homann N, Pauligk C, Illerhaus G, Martens UM,

Stoehlmacher J, et al. Effect of neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed

by surgical resection on survival in patients with limited metastatic

gastric or gastroesophageal junction cancer: the AIO-FLOT3 trial.

JAMA Oncol. 2017;3:1237-44. Crossref

27. Al-Batran SE, Hofheinz RD, Pauligk C, Kopp HG, Haag GM,

Luley KB, et al. Histopathological regression after neoadjuvant

docetaxel, oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and leucovorin versus

epirubicin, cisplatin, and fluorouracil or capecitabine in patients with

resectable gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction adenocarcinoma

(FLOT4-AIO): results from the phase 2 part of a multicentre, open-label,

randomised phase 2/3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17:1697-708. Crossref

28. Al-Batran SE, Homann N, Pauligk C, Goetze TO, Meiler J,

Kasper S, et al. Perioperative chemotherapy with fluorouracil

plus leucovorin, oxaliplatin, and docetaxel versus fluorouracil or

capecitabine plus cisplatin and epirubicin for locally advanced,

resectable gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction adenocarcinoma

(FLOT4): a randomised, phase 2/3 trial. Lancet. 2019;393:1948-57. Crossref

29. Washington K. 7th edition of the AJCC cancer staging manual:

stomach. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:3077-9. Crossref

30. Rice TW, Blackstone EH, Rusch VW. 7th edition of the AJCC

Cancer Staging Manual: esophagus and esophagogastric junction.

Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:1721-4. Crossref

31. Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC, editors. AJCC Cancer Staging

Manual (7th edition). Available from: https://www.facs.org/media/j30havyf/ajcc_7thed_cancer_staging_manual.pdf. Accessed 19 Feb 2025.

32. Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, Schwartz LH, Sargent D,

Ford R, et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid

tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer.

2009;45:228-47. Crossref

33. Ryan R, Gibbons D, Hyland JM, Treanor D, White A,

Mulcahy HE, et al. Pathological response following long-course

neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy for locally advanced rectal cancer.

Histopathology. 2005;47:141-6. Crossref

34. Department of Health and Human Services, United States

Government. Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events

(CTCAE) Version 5.0. 2017. Available from: https://ctep.cancer.gov/protocoldevelopment/electronic_applications/docs/ctcae_v5_quick_reference_5x7.pdf. Accessed 14 Feb 2025.

35. Biondi A, Persiani R, Cananzi F, Zoccali M, Vigorita V, Tufo A,

et al. R0 resection in the treatment of gastric cancer: room for

improvement. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:3358-70. Crossref

36. Brenner B, Shah MA, Karpeh MS, Gonen M, Brennan MF,

Coit DG, et al. A phase II trial of neoadjuvant cisplatin-fluorouracil

followed by postoperative intraperitoneal floxuridine-leucovorin

in patients with locally advanced gastric cancer. Ann Oncol.

2006;17:1404-11. Crossref

37. Kunisaki C, Akiyama H, Nomura M, Matsuda G, Otsuka Y, Ono HA,

et al. Surgical outcomes in patients with T4 gastric carcinoma. J

Am Coll Surg. 2006;202:223-30. Crossref

38. Schmidt B, Look-Hong N, Maduekwe UN, Chang K, Hong TS,

Kwak EL, et al. Noncurative gastrectomy for gastric adenocarcinoma

should only be performed in highly selected patients. Ann Surg

Oncol. 2013;20:3512-8. Crossref

39. Macdonald JS, Bendetti J, Smalley S, Haller DG, Hundahl S,

Jessup J, et al. Chemoradiation of resected gastric cancer: a 10-year

follow-up of the phase III trial INT0116 (SWOG 9008). J Clin

Oncol. 2009;27(15_supp):4515. Crossref

40. Ychou M, Boige V, Pignon JP, Conroy T, Bouché O, Lebreton G,

et al. Perioperative chemotherapy compared with surgery alone

for resectable gastroesophageal adenocarcinoma: an FNCLCC and

FFCD multicenter phase III trial. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:1715-21. Crossref

41. Du R, Hu P, Liu Q, Zhang J. Conversion surgery for unresectable

advanced gastric cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis.

Cancer Invest. 2019;37:16-28. Crossref

42. McNamee N, Nindra U, Shahnam A, Yoon R, Asghari R, Ng W,

et al. Haematological and nutritional prognostic biomarkers

for patients receiving CROSS or FLOT. J Gastrointest Oncol.

2023;14:494-503. Crossref

43. Deans DA, Wigmore SJ, de Beaux AC, Paterson-Brown S,

Garden OJ, Fearon KC. Clinical prognostic scoring system to

aid decision-making in gastro-oesophageal cancer. Br J Surg.

2007;94:1501-8. Crossref

44. Diakos CI, Charles KA, McMillan DC, Clarke SJ. Cancer-related inflammation and treatment effectiveness. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:e493-503. Crossref

45. Arigami T, Uenosono Y, Matsushita D, Yanagita S, Uchikado Y,

Kita Y, et al. Combined fibrinogen concentration and neutrophil-lymphocyte

ratio as a prognostic marker of gastric cancer. Oncol

Lett. 2016;11:1537-44. Crossref

46. Shitara K, Rha SY, Wyrwicz LS, Oshima T, Karaseva N, Osipov M,

et al. Neoadjuvant and adjuvant pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy

in locally advanced gastric or gastro-oesophageal cancer

(KEYNOTE-585): an interim analysis of the multicentre, double-blind,

randomised phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2024;25:212-24. Crossref

47. Janjigian YY, Al-Batran SE, Wainberg ZA, Van Cutsem E,

Molena D, Muro K, et al. LBA73 Pathological complete

response (pCR) to durvalumab plus 5-fluorouracil, leucovorin,

oxaliplatin and docetaxel (FLOT) in resectable gastric and

gastroesophageal junction cancer (GC/GEJC): interim results of

the global, phase III MATTERHORN study [abstract]. Ann Oncol.

2023;34(suppl_2):S1315-6. Crossref

48. Al-Batran SE, Shitara K, Folprecht G, Moehler MH, Goekkurt E,

Ben-Aharon I, et al. Pembrolizumab plus FLOT vs FLOT as

neoadjuvant and adjuvant therapy in locally advanced gastric and

gastroesophageal junction cancer: interim analysis of the phase

3 KEYNOTE-585 study [abstract]. J Clin Oncol. 2024;42(3_suppl):247. Crossref