Pancreatic Cystic Lymphangioma Complicated by Haemorrhagic Infarction: A Case Report

CASE REPORT

Hong Kong J Radiol 2025 Mar;28(1):e50-54 | Epub 18 March 2025

Pancreatic Cystic Lymphangioma Complicated by Haemorrhagic Infarction: A Case Report

Patricia Jarmin Lopez Pua1, Florence Los Baños1, Honey Lee Tan2, Victor Tatco2

1 Institute of Radiology, St Luke’s Medical Center, Quezon City, The Philippines

2 Institute of Surgery, St Luke’s Medical Center, Quezon City, The Philippines

Correspondence: Dr PJL Pua, Institute of Radiology, St Luke’s Medical Center, Quezon City, The Philippines. Email: patriciajarmin.pua@gmail.com

Submitted: 16 August 2023; Accepted: 9 February 2024.

Contributors: All authors designed the study, acquired the data, analysed the data, drafted the manuscript, and critically revised the manuscript

for important intellectual content. All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and

take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Funding/Support: This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data Availability: All data generated or analysed during the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: The study was approved by the St Luke’s Institutional Ethics Review Committee, the Philippines (Ref No.: SL-23172). Informed consent for the study and publication was obtained from the patient.

INTRODUCTION

Pancreatic cystic lymphangioma or lymphatic

malformation in the pancreas is an extremely rare entity

resulting from lymphatic flow obstruction. It comprises

<1% of all types of lymphatic malformations and about

0.2% of all cystic lesions of the pancreas.[1] Fewer than

100 cases have been reported in the literature.[2] Currently,

there are no guidelines for diagnosis and management.

Preoperative evaluation and management depend on

clinical presentation. Computed tomography (CT),

magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and ultrasonography

have been widely used for initial assessment but

histopathology remains the standard for diagnostic

confirmation.[3]

We report the case of a patient who presented to the

emergency department with severe right-sided abdominal

pain. Imaging studies revealed a large complex cystic

mass with unclear origin. The patient underwent

surgery that revealed pancreatic cystic lymphangioma

complicated by haemorrhagic infarction.

CASE PRESENTATION

A 43-year-old female presented to the emergency department of our institution in March 2022 with

sudden-onset severe right upper abdominal pain. Bedside

ultrasound in the emergency room revealed a large cystic

abdominal mass. There was no associated jaundice,

vomiting, weight loss or altered bowel movement and

no history of abdominal surgeries. Physical examination

revealed a slightly globular abdomen with epigastric

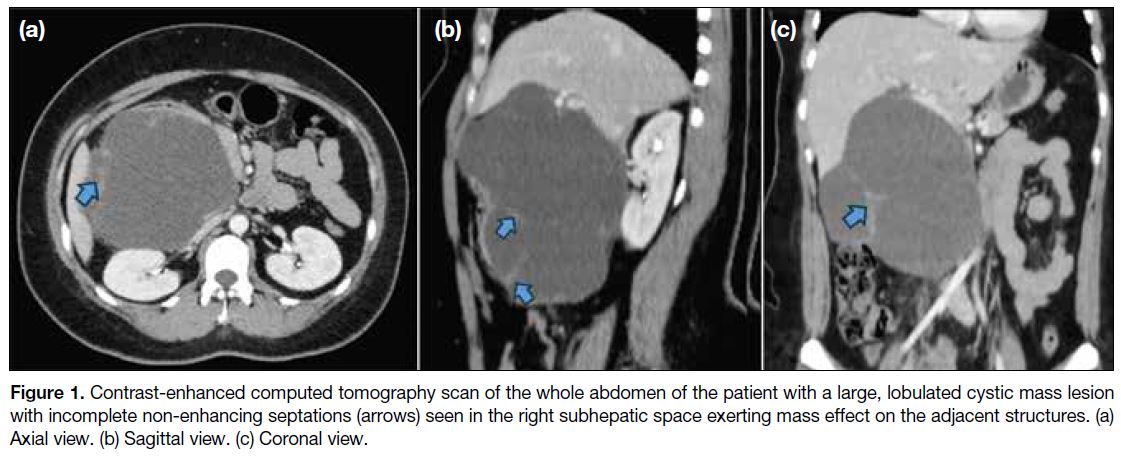

tenderness. Contrast-enhanced CT scan of the abdomen

(Figure 1) showed a lobulated cystic mass with thick

and incomplete minimally enhancing septations

measuring about 10.6 × 13.6 × 17 cm3 (anteroposterior × transverse × craniocaudal). Minimal surrounding fat

stranding densities were seen. The mass was located in

the right subhepatic space, close to the duodenum and

pancreatic head, exerting a mass effect on the liver and

gallbladder, superiorly, and on the right kidney, renal

vessels and inferior vena cava, posteriorly. Marked

luminal narrowing of the inferior vena cava was evident.

There were no enlarged abdominopelvic lymph nodes.

Differential diagnoses were mesenteric cyst, duplication

cyst and cystic neoplasm of the pancreas.

Figure 1. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan of the whole abdomen of the patient with a large, lobulated cystic mass lesion

with incomplete non-enhancing septations (arrows) seen in the right subhepatic space exerting mass effect on the adjacent structures. (a)

Axial view. (b) Sagittal view. (c) Coronal view.

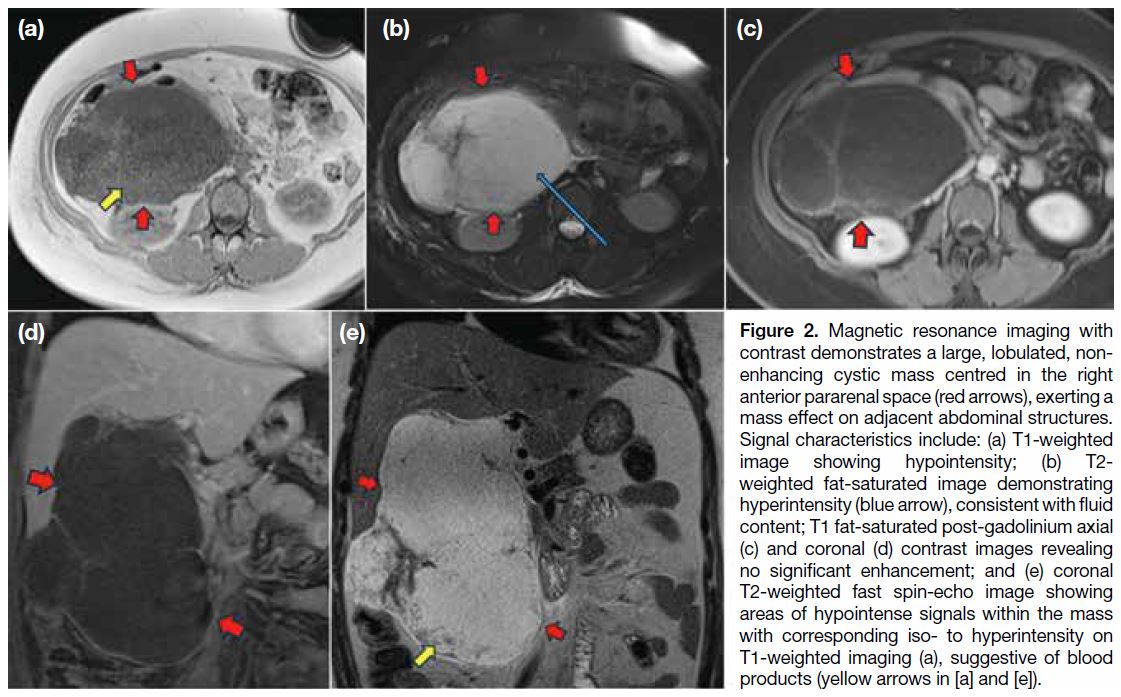

Subsequent magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography

with contrast (Figure 2) of the patient showed a predominantly T2 hyperintense lobulated mass lesion

measuring 10.5 × 14 × 17 cm3 (anteroposterior × transverse × craniocaudal) in the right anterior

pararenal space, extending superiorly to the subhepatic

region. It impinged on the inferior surface of the liver

and displaced the right mesocolic region inferiorly.

Some T1-weighted iso- to hyperintense signals with

corresponding T2-weighted hypointense signals were also seen, suggestive of blood products. There was

no diffusion restriction abnormality nor significant

enhancement. Compression of the adjacent duodenum,

pancreatic head/uncinate process, inferior vena cava,

right kidney and renal vessels was evident. The

pancreatic duct was not dilated. The main portal vein,

common hepatic artery and common bile ducts were

partially encased but did not appear infiltrated by the mass. There were no enlarged lymph nodes. Mild

abdominopelvic ascites was present.

Figure 2. Magnetic resonance imaging with

contrast demonstrates a large, lobulated, non-enhancing

cystic mass centred in the right

anterior pararenal space (red arrows), exerting a

mass effect on adjacent abdominal structures.

Signal characteristics include: (a) T1-weighted

image showing hypointensity; (b) T2-weighted fat-saturated image demonstrating

hyperintensity (blue arrow), consistent with fluid

content; T1 fat-saturated post-gadolinium axial

(c) and coronal (d) contrast images revealing

no significant enhancement; and (e) coronal

T2-weighted fast spin-echo image showing

areas of hypointense signals within the mass

with corresponding iso- to hyperintensity on

T1-weighted imaging (a), suggestive of blood

products (yellow arrows in [a] and [e]).

Laboratory examinations showed elevated level of

carbohydrate antigen 19-9 at 269.40 U/mL (normal

value = 0.00-37.00). Carcinoembryonic antigen level

was normal at 1.12 ng/mL (normal value < 2.5).

Initial considerations were retroperitoneal lymphatic

malformation or mucinous cystic neoplasm of the

pancreas.

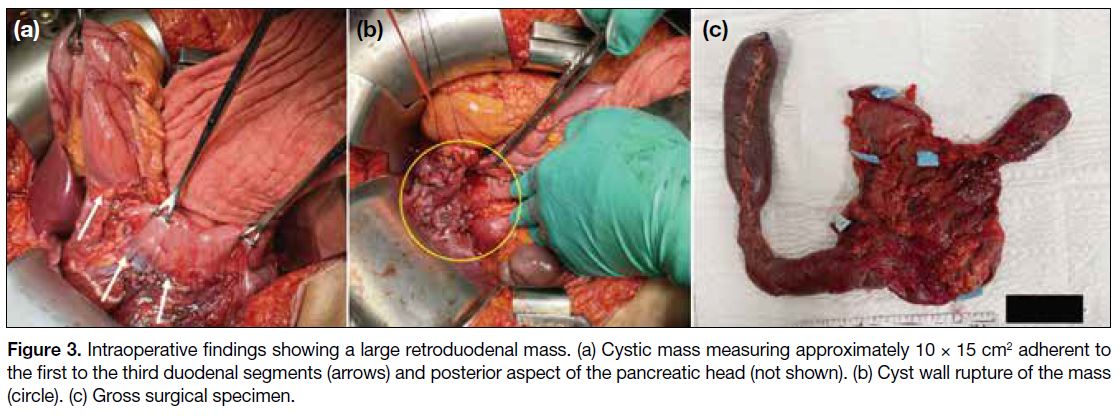

The patient underwent exploratory laparotomy (Figure 3)

that revealed a cystic mass adherent to the first to the third

duodenal segments and posterior aspect of the pancreatic head. It measured about 10 × 15 cm2 (width × length) and

displaced the portal vein and superior mesenteric vein

anteromedially, the duodenum, pancreatic head, vena

cava, and the right kidney posteriorly. The cystic mass

insinuated in between the portal vein and common bile

duct.

Figure 3. Intraoperative findings showing a large retroduodenal mass. (a) Cystic mass measuring approximately 10 × 15 cm2 adherent to

the first to the third duodenal segments (arrows) and posterior aspect of the pancreatic head (not shown). (b) Cyst wall rupture of the mass

(circle). (c) Gross surgical specimen.

Surgical rupture of the cyst drained approximately 1 L of dark serosanguineous fluid. Pancreaticoduodenectomy

was then performed. Histopathology revealed a

pancreatic cystic lymphangioma with haemorrhagic

infarction (Figure 4). There was no evidence of dysplasia

or malignancy. The patient’s postoperative course was

unremarkable.

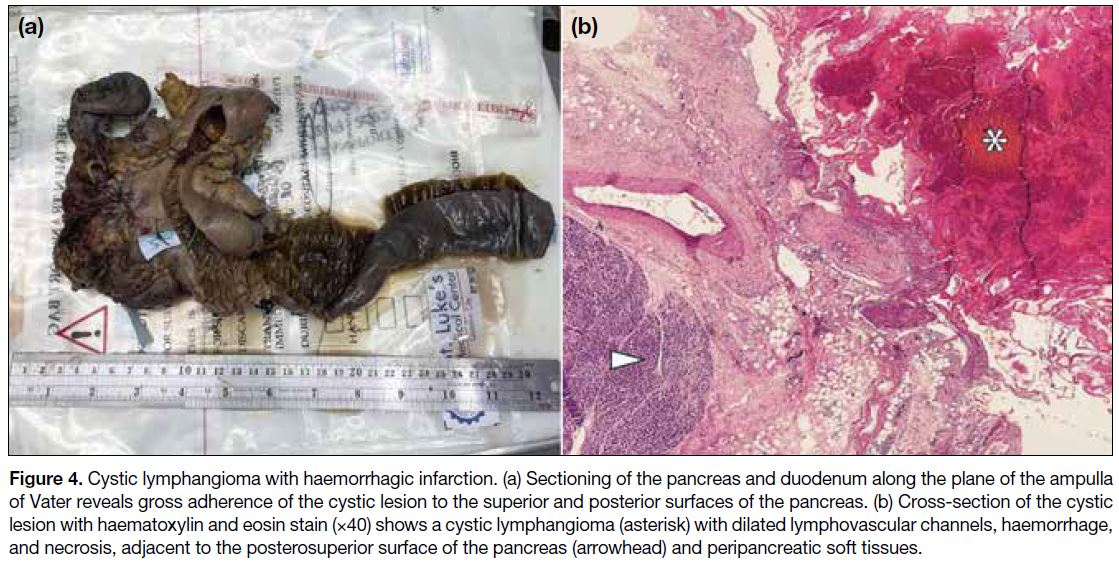

Figure 4. Cystic lymphangioma with haemorrhagic infarction. (a) Sectioning of the pancreas and duodenum along the plane of the ampulla

of Vater reveals gross adherence of the cystic lesion to the superior and posterior surfaces of the pancreas. (b) Cross-section of the cystic

lesion with haematoxylin and eosin stain (×40) shows a cystic lymphangioma (asterisk) with dilated lymphovascular channels, haemorrhage,

and necrosis, adjacent to the posterosuperior surface of the pancreas (arrowhead) and peripancreatic soft tissues.

DISCUSSION

Lymphangiomas are benign lymphatic malformations in

the pancreas as a result of blockage of lymphatic outflow.

Most cases are asymptomatic and an incidental finding

on imaging. Nonetheless, the patient may present with

symptoms secondary to mass effect such as abdominal

pain, discomfort, and a palpable abdominal mass.[3] [4] There

is a female preponderance with mean age at presentation

of 28.9 years.[5] Laboratory tests including tumour markers

are usually normal.[5] In our case, there were signs and

symptoms of acute abdomen and an elevated level of

carbohydrate antigen 19-9, characteristics that may be

atypical for pancreatic lymphangioma.

Radiological imaging has a role in preoperative

assessment of pancreatic lymphangiomas. These lesions

may mimic other pancreatic cystic masses including

mucinous cystic neoplasm, pseudocysts and cystic

neuroendocrine tumours, making preoperative diagnosis

difficult.[6] [7] On CT and MRI, pancreatic lymphangiomas

appear as encapsulated homogeneous cystic masses,

as in our patient. These lesions may show enhancing

septations and occasionally contain phleboliths.[7] The

presence of T1 hyperintense signals within cystic masses

indicates lipid, highly proteinaceous, or haemorrhagic

content.[8] In our case, it is interesting to note that the

suggestive blood products present within the mass may

have been congruent with the haemorrhagic infarction

seen intraoperatively. To the best of our knowledge,

there have been no prior reported cases of haemorrhagic

lymphangiomas arising in the pancreas.

On histopathology, lymphangiomas appear as multilocular cysts representing dilated lymphatic

channels containing serous, serosanguineous, or chylous

fluid. The cyst walls are lined with endothelial cells

and are composed of varying degrees of collagenous

connective tissue and smooth muscle.[7]

Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration

may help establish a definitive preoperative diagnosis

and enable conservative management of asymptomatic

patients.[9] Future studies are encouraged to establish

guidelines for management of pancreatic lymphatic

malformations.[9]

The treatment of choice of pancreatic lymphangiomas is

complete surgical resection accompanied by a low chance

of recurrence. Overall prognosis is excellent. Surgery

is often required for symptom control or diagnosis.[10]

An imaging study on follow-up is an alternative for asymptomatic patients.

CONCLUSION

Although rare, pancreatic lymphangiomas should

be included in the differential diagnoses of complex

pancreatic cystic lesions, especially in asymptomatic

women. Preoperative diagnosis with diagnostic imaging

is usually inconclusive but may determine the extent

of the mass and its relationship to adjacent structures.

A combination of imaging studies and analysis on

endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration can

provide a definitive preoperative diagnosis.

Since lymphangiomas are considered benign,

a conservative approach may be reasonable in

asymptomatic patients and stable lesions once tissue

diagnosis is confirmed. Nonetheless these lesions may be

locally invasive. Radiological imaging, particularly CT

and MRI, may play a role in determining complications

such as obstruction, rupture, or infection that warrant

surgical intervention. Guidelines for appropriate

selection of conservative approach versus surgical

intervention should be established.

REFERENCES

1. Carvalho D, Costa M, Russo P, Simas L, Baptista T, Ramos G.

Cystic pancreatic lymphangioma—diagnostic role of endoscopic

ultrasound. GE Port J Gastroenterol. 2016;23:254-8. Crossref

2. Karajgikar J, Deshmukh S. Pancreatic lymphangioma: a case report

and literature review. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2019;43:242-4. Crossref

3. Viscosi F, Fleres F, Mazzeo C, Vulcano I, Cucinotta E. Cystic

lymphangioma of the pancreas: a hard diagnostic challenge between

pancreatic cystic lesions—review of recent literature. Gland Surg.

2018;7:487-92. Crossref

4. Chen D, Feng X, Lv Z, Xu X, Ding C, Wu J. Cystic lymphangioma

of pancreas: a rare case report and review of the literature. Medicine

(Baltimore). 2018;97:e11238. Crossref

5. Leung TK, Lee CM, Shen LK, Chen YY. Differential diagnosis of

cystic lymphangioma of the pancreas based on imaging features. J

Formos Med Assoc. 2006;105:512-7. Crossref

6. Anbardar MH, Soleimani N, Aminzadeh Vahedi A, Malek-Hosseini

SA. Large cystic lymphangioma of pancreas mimicking mucinous

neoplasm: case report with a review of histological differential

diagnosis. Int Med Case Rep J. 2019;12:297-301. Crossref

7. Manning MA, Srivastava A, Paal EE, Gould CF, Mortele KJ.

Nonepithelial neoplasms of the pancreas: radiologic-pathologic

correlation, part 1—benign tumors: from the radiologic pathology

archives. Radiographics. 2016;36:123-41. Crossref

8. Stoupis C, Ros PR, Williams JL. Hemorrhagic lymphangioma

mimicking hemoperitoneum: MR imaging diagnosis. J Magn Reson

Imaging. 1993;3:541-2. Crossref

9. Chen Q, Wang Y, Wang J, Hou W, Zou B, Cheng B. Diagnosis

of pancreatic cystic lymphangioma in an 11-year-old boy with

endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration: a case report.

Int J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis. 2016;6:114-20. Crossref

10. Cherk M, Nikfarjam M, Christophi C. Retroperitoneal

lymphangioma. Asian J Surg. 2006;29:51-4. Crossref