Management and Prognosis of Breast Intraductal Papilloma Diagnosed by Core Needle Biopsy: Comparing Vacuum-assisted Excision, Surgical Excision, and Surveillance

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Hong Kong J Radiol 2025 Mar;28(1):e14-22 | Epub 17 March 2025

Management and Prognosis of Breast Intraductal Papilloma Diagnosed by Core Needle Biopsy: Comparing Vacuum-assisted

Excision, Surgical Excision, and Surveillance

HL Chan1, KH Wong1, KF Tam1, HHL Chau2

1 Department of Radiology, North District Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

2 Department of Imaging and Interventional Radiology, Prince of Wales Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

Correspondence: Dr HL Chan, Department of Radiology, North District Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China. Email: hollischanrad@gmail.com

Submitted: 20 June 2023; Accepted: 8 November 2023.

Contributors: All authors designed the study. HLC and KHW acquired the data. All authors analysed the data. HLC and KHW drafted the

manuscript. KFT and HHLC critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors had full access to the data,

contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Funding/Support: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data Availability: All data generated or analysed during the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: This research was approved by the Joint Chinese University of Hong Kong–New Territories East Cluster Clinical Research Ethics Committee, Hong Kong (Ref No.: 2023.169). The requirement for patient consent was waived by the Committee due to the retrospective nature of the research.

Abstract

Introduction

Intraductal papilloma (IDP) is a common breast lesion that is often excised, but the treatment of

choice for IDP without atypia diagnosed on core needle biopsy (CNB) remains controversial due to its low risk of

malignancy. Besides surgery, vacuum-assisted excision (VAE) has emerged as a less invasive alternative. This study

aimed to compare the management and prognosis of IDP without atypia diagnosed by CNB across surgical excision,

VAE and surveillance, and to identify risk factors predicting papilloma malignant transformation.

Methods

This single-centre retrospective review included 107 consecutive samples diagnosed with IDP without

atypia with ultrasound-guided CNB from 2016 to 2020. The patients underwent surgical excision, ultrasound-guided

VAE or surveillance. The malignant transformation and recurrence rates were evaluated, and potential risk factors

for malignant transformation were analysed.

Results

The overall malignant transformation rate was 3.7%. The malignant transformation rates were 10.3% in

the surgical excision group and 2.1% in the VAE group. No IDP recurrence was identified in either group. For the

group that underwent surveillance, none of the lesions showed significant size increase during follow-up. Lesions

≤1 cm and nonpalpable lesions showed low malignant transformation rates of 1.3% and 1.2%, respectively. Risk

factors for malignant transformation included larger size (p = 0.002), palpability (p = 0.016), multiple lesions (p = 0.045), and a positive family history of breast cancer (p = 0.035).

Conclusion

Imaging surveillance may be an alternative management option for IDP in low-risk groups given its

low malignant transformation rate. VAE is a safe and effective choice. Surgery may be considered for larger sized

lesions with risk factors.

Key Words: Biopsy, large-core needle; Papilloma, intraductal; Radiology information systems

中文摘要

芯針活檢診斷乳腺導管內乳頭狀瘤的治療和預後:比較真空輔助切除、手術切除和非外科監測

陳凱玲、黃健開、譚國輝、周海倫

引言

導管內乳頭狀瘤是一種常見的乳腺病變,通常外科切除,但由於其惡性風險較低,對於經芯針活檢診斷無異型增生導管內乳頭狀瘤的治療選擇仍存在爭議。除了手術之外,真空輔助切除成為創傷較小的替代方案。本研究旨在比較芯針活檢診斷的無異型增生導管內乳頭狀瘤的手術切除、真空輔助切除和非外科監測的治療和預後,並找出預測乳頭狀瘤惡變的風險因素。

方法

本單中心回顧性研究納入了2016至2020年間經超音波引導下的芯針活檢診斷為無異型增生導管內乳頭狀瘤的107例連續樣本。患者接受了手術切除、超音波引導下的真空輔助切除或非外科監測。我們評估了惡變和復發率,並分析了惡變的潛在風險因素。

結果

整體惡變率為3.7%。手術切除組的惡變率為10.3%,而真空輔助切除組的惡變率為2.1%。兩組均未發現導管內乳頭狀瘤復發。接受非外科監測組在隨訪期間沒有病變顯示出明顯大小增加。≤1 cm 的病灶和不可觸及病灶的惡變率低,分別為1.3%和1.2%。惡變的風險因素包括體積較大(p = 0.002)、可觸及(p = 0.016)、多發性病灶(p = 0.045)和乳癌陽性家族史(p = 0.035)。

結論

鑑於影像監測的惡變率低,因此它可以是治療低風險群導管內乳頭狀瘤的替代方案。真空輔助切除是安全有效的選擇。具有惡變風險因素的較大病變可以考慮外科手術。

INTRODUCTION

Intraductal papillomas (IDPs) of the breast are common

benign lesions that arise from the epithelium lining the

lactiferous ducts. They can be found incidentally during

mammography, ultrasonography (US), or magnetic

resonance imaging, or present with symptoms such as

nipple discharge, palpable masses, or asymptomatic.

IDPs can be classified as solitary or multiple, and with

or without atypia. IDPs without atypia are benign lesions

with a low risk of developing into breast cancer.[1] [2] [3]

However, IDPs with atypia have a higher risk of

malignant transformation. Consensus exists regarding the

need for surgical excision of IDP with atypia diagnosed

on core needle biopsy (CNB), owing to a pooled

malignant transformation rate of up to 36.9%.[4] However,

despite numerous published studies, the management of

IDP without atypia diagnosed by CNB is still a matter

of debate.[5] Surgical excision has been the standard

approach for many years, with the goal of establishing

a definitive diagnosis, excluding coexisting malignancy,

and preventing progression to cancer. It is the most

commonly used management strategy, but it has some

drawbacks, such as the need for general anaesthesia,

potential complications, and possible deformity. In recent

years, vacuum-assisted excision (VAE) has emerged as an alternative to surgical excision, as it is less invasive,

more convenient, and associated with lower morbidity.[6]

Follow-up breast imaging has also been proposed as

an alternative to excisional management in selected

patients, with the advantage of avoiding the risks and

complications associated with surgery.[7]

Studies have reported the malignant transformation

rate and the recurrence rate after surgical excision or

VAE of IDP without atypia.[1] [7] However, there is still

no consensus on the best management strategy for this

lesion, and some studies have suggested that follow-up

breast imaging may be a safe and effective management

strategy in selected patients.[3] [4] [7] The aim of this study was

to estimate the feasibility of VAE or surveillance for the

management of IDP without atypia compared to surgical

excision, with regard to malignant transformation rate

and the recurrence rate. The potential risk factors for

malignant transformation were also analysed.

METHODS

We conducted a retrospective analysis of 173 consecutive

biopsy specimens of IDP without atypia obtained with

CNB under US guidance at our centre between 1 January

2016 and 31 December 2020. We excluded patients with ipsilateral breast cancer who underwent total mastectomy

and patients lost to follow-up. For multiple IDPs

diagnosed on CNB in the same patient, only the largest

IDP was included in the study and the rest were excluded.

The management strategy for each patient was

determined in multidisciplinary team meetings with

breast radiologists, breast surgeons, and pathologists.

The management options included surgical excision,

VAE, and surveillance by follow-up breast US. During

the multidisciplinary meetings, pathologists meticulously

reviewed the tissue slices for any atypical features and

the adequacy of core samples for diagnostic confidence.

Radiologists analysed the ultrasound images to establish

concordance between radiological and pathological

findings, making sure no possible malignancy was

present. Additionally, the feasibility of surgery or

VAE was assessed based on factors such as lesion size,

location (peripheral or central) and depth from the skin.

Multidisciplinary team members also identified potential

risk factors associated with malignant transformation,

including patient demographics, family history of

breast cancer, larger lesion size, and related symptoms.

Most importantly, patientsʼ willingness to proceed to

lesion removal or preference of imaging surveillance

was addressed. Ultimately, the decision to pursue

imaging surveillance, surgery or VAE was guided by a

multidisciplinary evaluation of risks and benefits, and

most importantly respecting the patient’s wishes.

For patients in the surgical excision group, the surgical

excision was performed by the surgical team, and the

information was extracted from the surgical record. For

patients in the imaging surveillance group, the size and

location of each lesion were recorded at the time of initial

diagnosis and latest follow-up.

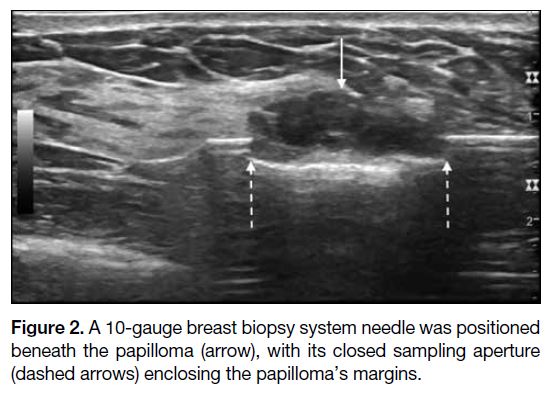

For patients in the VAE group, the procedure was

performed by radiologists in our department. The

technique of US-guided VAE is illustrated in Figures 1, 2 and 3. The targeted lesion, which was previously proven

IDP without atypia on CNB, would first be identified on

preliminary US. Infusion to the skin with 1 to 5 mL of 2%

lignocaine and the perilesional region with 5 to 10 mL

1:200 000 adrenaline was used as local anaesthesia. The

probe was introduced through a small skin incision and

the IDP was positioned within the margins of the closed

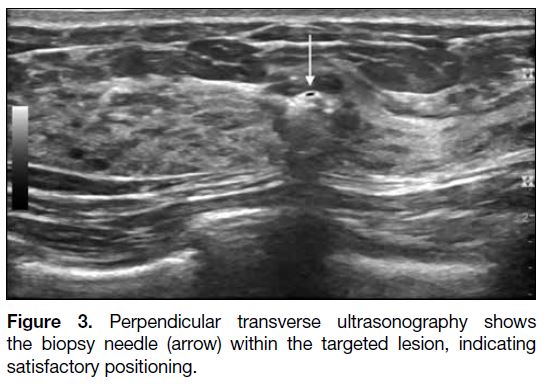

sampling aperture (Figure 2) and satisfactory positioning

was confirmed on imaging in a plane perpendicular to

the first image (Figure 3). In our institute, we used a

10-gauge EnCor Enspire Breast Biopsy System needle

(SenoRx, Aliso Viejo [CA], United States). Samples

were taken with adjustment (rotation and repositioning)

of the needle, if necessary, until the papilloma was

indiscernible on US.

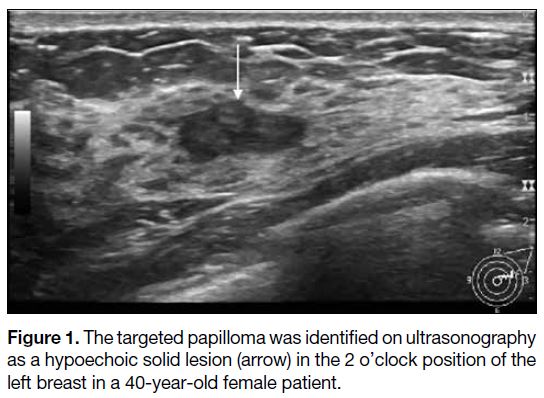

Figure 1. The targeted papilloma was identified on ultrasonography

as a hypoechoic solid lesion (arrow) in the 2 o’clock position of the

left breast in a 40-year-old female patient.

Figure 2. A 10-gauge breast biopsy system needle was positioned

beneath the papilloma (arrow), with its closed sampling aperture

(dashed arrows) enclosing the papilloma’s margins.

Figure 3. Perpendicular transverse ultrasonography shows

the biopsy needle (arrow) within the targeted lesion, indicating

satisfactory positioning.

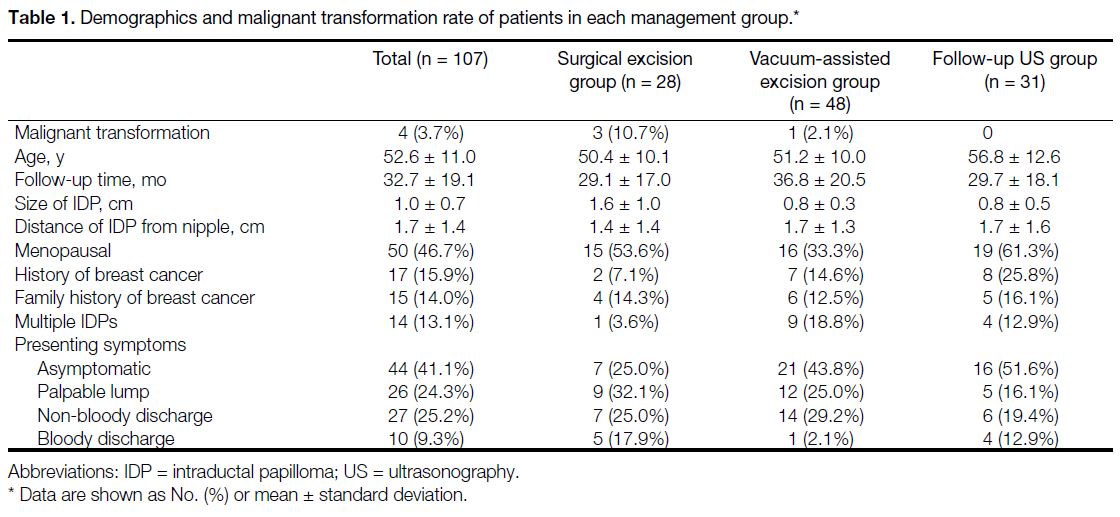

Patients’ demographics and clinical data, radiological

data, histopathological diagnosis, malignant

transformation rates, and recurrence rates were recorded (Table 1). These data were extracted from the electronic

health record and the radiology information system.

Table 1. Demographics and malignant transformation rate of patients in each management group.

On ultrasound, IDPs typically present as solid or

complex cystic and solid masses. It is also possible to

identify the lesion within a dilated duct in some cases,

as demonstrated in Figure 1. The size of the IDP was

measured as the longest dimension on ultrasound, and

the location of the lesion was measured as the distance

from the nipple (in cm). The malignant transformation

rate was defined as the percentage of patients who were

diagnosed with malignancy on surgical excision or VAE

after the initial diagnosis of IDP without atypia. The

recurrence rate was defined as the percentage of patients

who were found to have evidence of recurrence (i.e., the

rate of returning to previous histological grade) of the

lesion on follow-up imaging after surgical excision or

VAE. A patient was considered to have multiple IDPs

if there was a previous history of IDP, or if multiple

biopsies had been performed at different sites within 60

days diagnosing IDPs.

A previous personal history of breast cancer included a

history of invasive disease or ductal carcinoma in situ.

The follow-up period was defined as the time from the

initial diagnosis to the last imaging study.

Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using commercial

software SPSS (Windows version 26.0; IBM Corp,

Armonk [NY], United States). Categorical variables

were expressed as frequencies and percentages, and continuous variables were expressed as means ±

standard deviations (SDs). The Pearson Chi squared test

or Fisher’s exact test was used to compare the categorical

variables, and the independent t test or Mann-Whitney

U test was used to compare the continuous variables

between groups. A p value of < 0.05 was considered

significant.

RESULTS

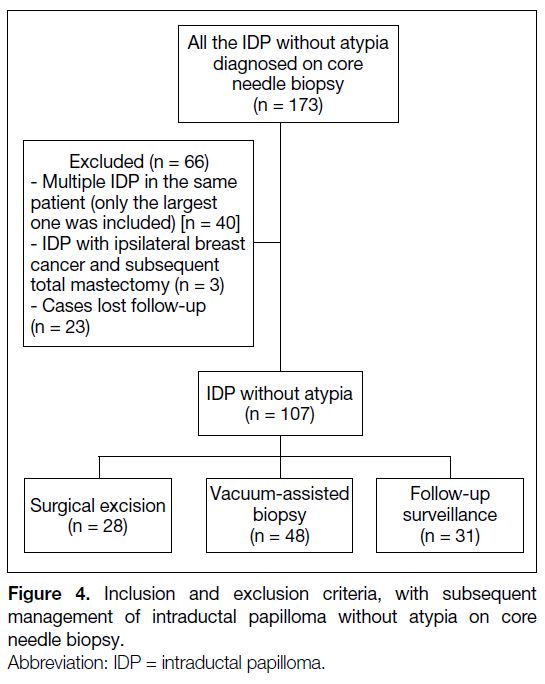

The 173 consecutive samples with pathological

diagnosis of IDP without atypia in 2016 to 2020 were

reviewed. After excluding lesions except the largest one

in one patient with multiple IDPs (n = 40), patients with

ipsilateral breast cancer with total mastectomy (n = 3)

and patients who were lost to follow-up (n = 23), we

included 107 patients for subsequent analysis (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Inclusion and exclusion criteria, with subsequent

management of intraductal papilloma without atypia on core

needle biopsy.

Malignant Transformation Rate

The demographics and malignant transformation rates

of the patients are shown in Table 1. The mean age of

the study population was 52.6 years (SD = 11.0, range = 29-75) and the mean follow-up time was 32.7 months

(SD = 19.1, range = 3-77). All patients were female.

Of the 107 patients in the study, four (3.7%) were

diagnosed with malignancy after excision, for a

malignant transformation rate in the surgical excision

group of 10.7% and 2.1% in the VAE group. There was

no recurrence identified in either group. For the group

that underwent follow-up breast imaging, none of the

lesions showed increase in size during a mean follow-up

of 29.7 months (SD = 18.1, range = 5-63).

The mean size of the lesions in the surgical excision

group was larger (1.6 cm) compared to the VAE group

(0.8 cm) and the breast imaging follow-up group

(0.8 cm). The distance of the lesion from the nipple was

similar in all three groups (1.4 cm in the surgical excision

group, 1.7 cm in the VAE group, and 1.7 cm in the breast

imaging follow-up group) [Table 1].

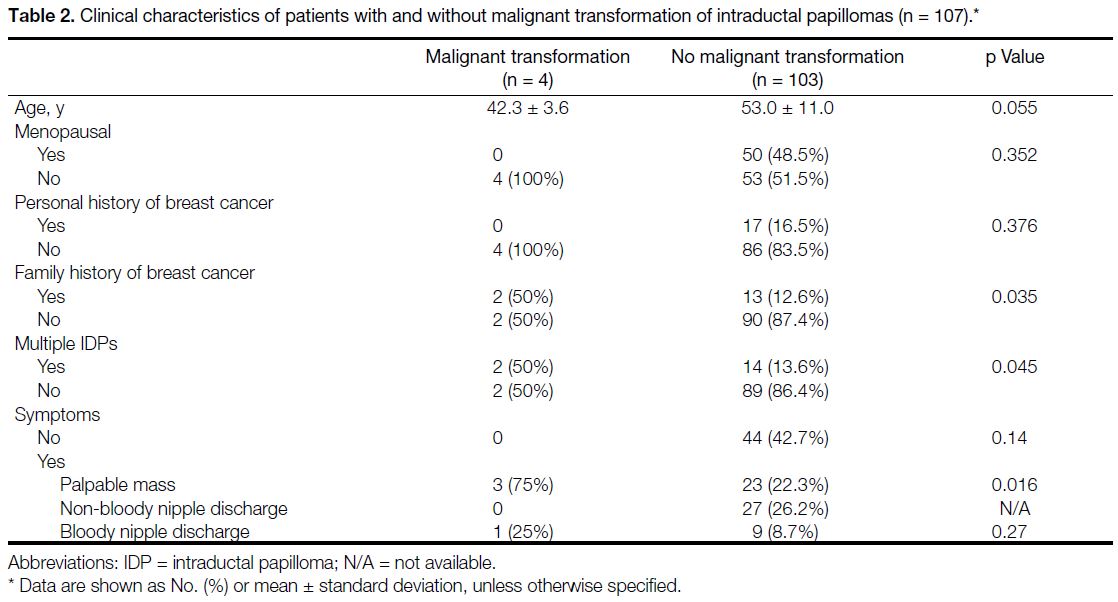

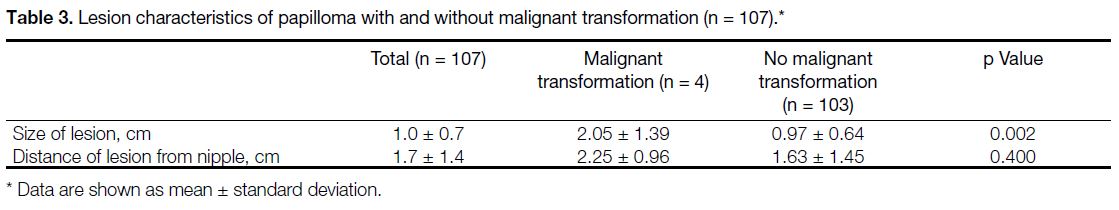

The clinical and lesion characteristics were analysed to

explore the potential association with histopathological

malignant transformation. The results of the marginal

analysis revealed that family history of breast cancer

(p = 0.035), presenting symptom of palpable mass

(p = 0.016), multiple IDPs (p = 0.045), and lesion

size (p = 0.002) were significantly associated with

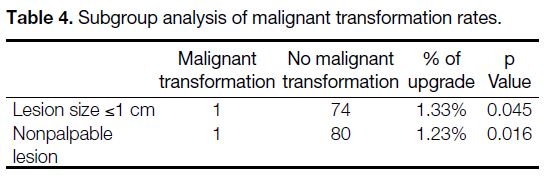

malignant transformation (Tables 2 and 3). Lesions

≤1 cm and nonpalpable lesions showed low upgrade

rates (i.e., malignant transformation rates) of 1.33% and

1.23%, respectively (Table 4). Although the presenting

symptom of bloody nipple discharge was more frequent

in the malignant transformation group, it did not reach

statistical significance (Table 2). Similarly, lesions that

were located farther from the nipple were also found to

be more frequent in the malignant transformation group,

but this did not reach statistical significance either (p = 0.400). There were no significant differences in patients’ age (p = 0.055), menopausal status (p = 0.352),

or personal history of breast cancer (p = 0.376) among

the malignant transformation group versus the non-malignant

transformation group (Table 2).

Table 2. Clinical characteristics of patients with and without malignant transformation of intraductal papillomas (n = 107).

Table 3. Lesion characteristics of papilloma with and without malignant transformation (n = 107).

Table 4. Subgroup analysis of malignant transformation rates.

Of the four cases that underwent malignant

transformation, one was invasive ductal carcinoma and

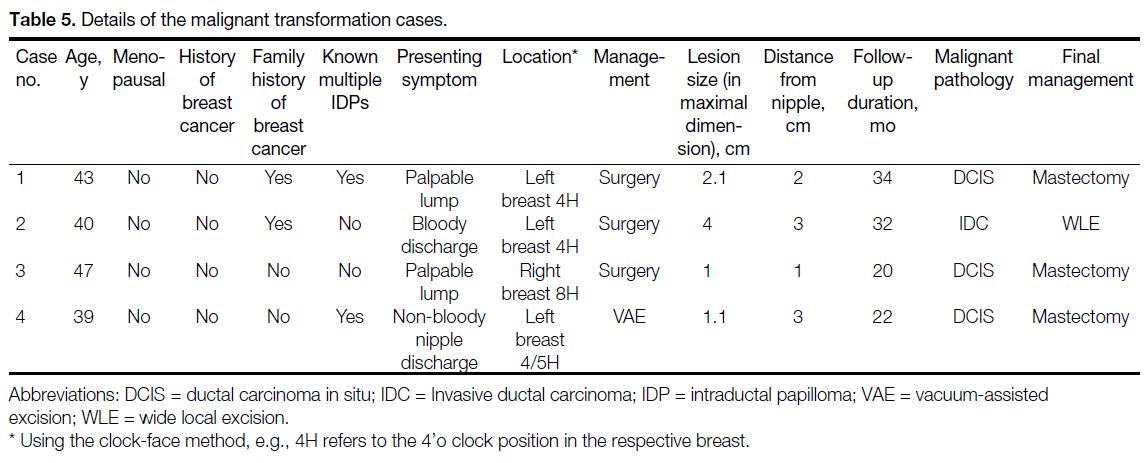

the remaining three were ductal carcinoma in situ. Table 5 summarises the clinical and radiological details of these cases.

Table 5. Details of the malignant transformation cases.

Safety and Efficacy of Vacuum-assisted

Excision

During each VAE procedure, the lesion was removed

with real-time US guidance until it became completely

undetectable on US. The number of cores taken

depended on the size of the lesion and the position of the

VAE needle. The number of cores collected had a mean

of 8.43 per procedure (SD = 2.35).

Common complications of VAE include haematomas,

pain, and ecchymosis.[8] These are usually self-limiting

and do not require further medical attention and

management.[9] Any that may have developed after the

patient has left our department were not documented in

the radiological procedure report.

The procedure duration of VAE was documented

based on the time log on US capture images which

indicated the amount of time the radiologist spent for

the procedure, from the first captured US image to the

final image. The mean procedure time was 18 minutes

(SD = 6.44). Note that the documented procedure time did

not include post-procedure wound care, wound dressing,

or manual compression (routine postprocedural manual

compression of 10 minutes to ensure haemostasis).

DISCUSSION

Breast IDP without atypia can be difficult to diagnose

accurately; it is impossible to predict its malignant

transformation potential using radiological imaging

alone.[1] [10] [11] CNB is often used to obtain the diagnosis,

but there is controversy whether surgical excision is

necessary. In our study, we found that the malignant

transformation rate was 3.7% in the total study population,

consistent with published literature malignancy ranges

from 0 to 29%.[1] [2] [3] [12] [13] [14] [15] [16] [17]

Surgical excision has traditionally been the standard

management strategy for breast IDP,[18] [19] but VAE has

gained popularity in recent years due to its minimally invasive nature.[6] In our study, we found that there was

no recurrence of papillomas in patients undergoing

VAE with a mean follow-up period of 36.8 months

(SD = 20.5) and those undergoing surgical excision with

a mean follow-up period of 29.1 months (SD = 17.0)

[Table 1], suggesting that both strategies are effective in

preventing recurrence.

VAE is a more minimally invasive approach compared

with surgical excision. It has a shorter procedure time,

requiring only local anaesthesia, and results in minimal

scarring and a lower possibility of breast deformity.

Complication rates are very low and are self-limited.[20] Therefore, VAE is particularly suitable for low-risk

lesions and patients with cosmesis concern.

However, there are several drawbacks of VAE. First,

VAE removes the lesion in a ‘piecemeal’ fashion, which

precludes pathologists from assessing the margins of the

excision.[21] Also, the completeness of excision relies on

the sonographic appearance of the lesion. IDP can grow

into small branches of the ducts. There is difficulty in

differentiating adherent debris from IDP, especially

in peripheral ducts.[10] [22] Therefore, there is a potential

increased risk of residual lesional tissue.[23] Lastly, there

is a size limit for VAE, as larger sized lesions are

more technically difficult to excise, with a high risk of

haemorrhage and incomplete excision. Surgical excision

is preferred for lesions >2.5 cm.[24]

Our study also found that breast imaging follow-up

alone may be a reasonable management strategy for

selected patients with IDP without atypia. Breast IDPs

without atypia had a low malignant transformation rate of 3.7% in our study. However, the overall malignant

transformation rate in our study remained higher

than the 2% threshold in category 3 of the American

College of Radiology Breast Imaging Reporting and

Data System (BI-RADS).[25] This may make radiologists

reluctant to assign IDPs without atypia for follow-up

surveillance only. Nonetheless, for IDPs of sizes ≤1 cm

and nonpalpable lesions, the percentage of upgrade

to malignancy were 1.3% and 1.2% respectively,

justified to be classified as BI-RADS category 3 lesions.

Additionally, in our study, none of the patients in the

surveillance group experienced a significant increase

in lesion size or malignant transformation during a

mean follow-up of 29.7 months. This is also consistent

with reported literature.[26] [27] Therefore, we propose that

lesions with lower risk (≤1 cm or nonpalpable) and/or

without any risk factors (i.e., positive family history

of breast cancer and/or multiple IDPs) are justified to

undergo follow-up imaging surveillance in accord with

BI-RADS.

Research has been carried out to identify the possible

risk factors for malignant transformation. In our study,

we identified several associated factors in line with

previous studies, including lesion size,[26] [27] [28] [29] palpability,[26] [30]

multiplicity,[28] and a family history of breast cancer.[28]

Previous studies have suggested that older age correlates

with higher potential for malignant transformation.[14] [31] [32]

However, in our study, we could not demonstrate such

correlation.

Limitations

Our study has several limitations. First, it was a

retrospective study conducted at a single institution, which may limit the generalisability of our findings. Second, as

a retrospective study, the assignment of patients to each

management group was based on multiple factors rather

than randomisation, which resulted in selection bias and

therefore may be the reason for the different malignant

transformation rates in the three groups. Third, the sample

size was relatively small, which limits the statistical

power of our study. Meanwhile, the types of core biopsy

needle and the number of passes were not documented,

which may have affected the diagnostic accuracy of

CNB. Also, the follow-up period was relatively short,

and longer follow-up may be necessary to fully evaluate

the efficacy of each treatment approach. Lastly, as a

retrospective study, there was no established protocol

specified for IDP imaging follow-up. The follow-up

radiological examination appointment was assigned as

per clinical request. This would be a very important topic

for future study.

CONCLUSION

Our study confirmed low malignant transformation

and recurrence rates of IDP without atypia. Follow-up

imaging surveillance for low-risk lesions may be a

promising alternative management. We also suggest the

feasibility of using VAE instead of surgical excision

when clinically indicated, as a less invasive yet safe and

effective method of choice. Patients who undergo follow-up

with breast imaging should be closely monitored

for changes in the lesion size and should be advised to

undergo biopsy or excision if there is any suspicion of

malignancy. Surgery may be considered for larger or

palpable lesions, as well as for patients with multiple

IDPs or a positive family history of breast cancer, due

to their association with an increased risk of malignant transformation. Further studies with larger sample sizes

and longer follow-up periods are needed to validate our

findings.

REFERENCES

1. Pareja F, Corben AD, Brennan SB, Murray MP, Bowser ZL,

Jakate K, et al. Breast intraductal papillomas without atypia in

radiologic-pathologic concordant core-needle biopsies: rate of

upgrade to carcinoma at excision. Cancer. 2016;122:2819-27. Crossref

2. Maxwell AJ, Mataka G, Pearson JM. Benign papilloma diagnosed

on image-guided 14-G core biopsy of the breast: effect of lesion

type on likelihood of malignancy at excision. Clin Radiol.

2013;68:383-7. Crossref

3. Nayak A, Carkaci S, Gilcrease MZ, Liu P, Middleton LP,

Bassett RL Jr, et al. Benign papillomas without atypia diagnosed

on core needle biopsy: experience from a single institution and

proposed criteria for excision. Clin Breast Cancer. 2013;13:439-49. Crossref

4. Wen X, Cheng W. Nonmalignant breast papillary lesions at core-needle

biopsy: a meta-analysis of underestimation and influencing

factors. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20:94-101. Crossref

5. Dillon MF, McDermott EW, Hill AD, O’Doherty A, O’Higgins N,

Quinn CM. Predictive value of breast lesions of “uncertain

malignant potential” and “suspicious for malignancy” determined

by needle core biopsy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14:704-11. Crossref

6. Wang ZL, Liu G, Huang Y, Wan WB, Li JL. Percutaneous

excisional biopsy of clinically benign breast lesions with vacuumassisted

system: comparison of three devices. Eur J Radiol.

2012;81:725-30. Crossref

7. Moynihan A, Quinn EM, Smith CS, Stokes M, Kell M, Barry JM,

et al. Benign breast papilloma: is surgical excision necessary?

Breast J. 2020;26:705-10. Crossref

8. Yoo HS, Kang WS, Pyo JS, Yoon J. Efficacy and safety of

vacuum-assisted excision for benign breast mass lesion: a metaanalysis.

Medicina (Kaunas). 2021;57:1260. Crossref

9. Wang WJ, Wang Q, Cai QP, Zhang JQ. Ultrasonographically

guided vacuum-assisted excision for multiple breast masses:

non-randomized comparison with conventional open excision. J

Surg Oncol. 2009;100:675-80. Crossref

10. Lam WW, Chu WC, Tang AP, Tse G, Ma TK. Role of radiologic

features in the management of papillary lesions of the breast. AJR

Am J Roentgenol. 2006;186:1322-7. Crossref

11. Shouhed D, Amersi FF, Spurrier R, Dang C, Astvatsaturyan K,

Bose S, et al. Intraductal papillary lesions of the breast: clinical

and pathological correlation. Am Surg. 2012;78:1161-5. Crossref

12. Ko D, Kang E, Park SY, Kim SM, Jang M, Yun BL, et al. The

management strategy of benign solitary intraductal papilloma on

breast core biopsy. Clin Breast Cancer. 2017;17:367-72. Crossref

13. Holley SO, Appleton CM, Farria DM, Reichert VC, Warrick J,

Allred DC, et al. Pathologic outcomes of nonmalignant papillary

breast lesions diagnosed at imaging-guided core needle biopsy.

Radiology. 2012;265:379-84. Crossref

14. Youk JH, Kim EK, Kwak JY, Son EJ, Park BW, Kim SI. Benign

papilloma without atypia diagnosed at US-guided 14-gauge core-needle

biopsy: clinical and US features predictive of upgrade to

malignancy. Radiology. 2011;258:81-8. Crossref

15. Tseng HS, Chen YL, Chen ST, Wu YC, Kuo SJ, Chen LS, et al.

The management of papillary lesion of the breast by core needle

biopsy. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2009;35:21-4. Crossref

16. Sohn YM, Park SH. Comparison of sonographically guided core

needle biopsy and excision in breast papillomas: clinical and

sonographic features predictive of malignancy. J Ultrasound Med. 2013;32:303-11. Crossref

17. Lee SJ, Wahab RA, Sobel LD, Zhang B, Brown AL, Lewis K, et al.

Analysis of 612 benign papillomas diagnosed at core biopsy: rate

of upgrade to malignancy, factors associated with upgrade, and a

proposal for selective surgical excision. AJR Am J Roentgenol.

2021;217:1299-311. Crossref

18. Chang JM, Moon WK, Cho N, Han W, Noh DY, Park IA, et al.

Management of ultrasonographically detected benign papillomas

of the breast at core needle biopsy. AJR Am J Roentgenol.

2011;196:723-9. Crossref

19. Puglisi F, Zuiani C, Bazzocchi M, Valent F, Aprile G, Pertoldi B,

et al. Role of mammography, ultrasound and large core biopsy in

the diagnostic evaluation of papillary breast lesions. Oncology.

2003;65:311-5. Crossref

20. Ko KH, Jung HK, Youk JH, Lee KP. Potential application of

ultrasound-guided vacuum-assisted excision (US-VAE) for wellselected

intraductal papillomas of the breast: single-institutional

experiences. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19:908-13. Crossref

21. Brzuszkiewicz K, Hodorowicz-Zaniewska D, Miękisz J,

Matyja A. Comparison of two minimally invasive biopsy

techniques—Breast Lesion Excision System and vacuum-assisted

biopsy—for diagnosing and treating breast lesions. Arch Med

Sci. 2022;18:1453-9. Crossref

22. Rissanen T, Reinikainen H, Apaja-Sarkkinen M. Breast

sonography in localizing the cause of nipple discharge:

comparison with galactography in 52 patients. J Ultrasound Med.

2007;26:1031-9. Crossref

23. Ueng SH, Mezzetti T, Tavassoli FA. Papillary neoplasms of the

breast: a review. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133:893-907. Crossref

24. Rageth CJ, O’Flynn EA, Pinker K, Kubik-Huch RA, Mundinger A,

Decker T, et al. Second International Consensus Conference on

lesions of uncertain malignant potential in the breast (B3 lesions).

Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2019;174:279-96. Crossref

25. Eberl MM, Fox CH, Edge SB, Carter CA, Mahoney MC. BI-RADS classification for management of abnormal mammograms.

J Am Board Fam Med. 2006;19:161-4. Crossref

26. Kuehner G, Darbinian J, Habel L, Axelsson K, Butler S, Chang S,

et al. Benign papillary breast mass lesions: favorable outcomes

with surgical excision or imaging surveillance. Ann Surg Oncol.

2019;26:1695-703. Crossref

27. Wyss P, Varga Z, Rössle M, Rageth CJ. Papillary lesions of the

breast: outcomes of 156 patients managed without excisional

biopsy. Breast J. 2014;20:394-401. Crossref

28. Liberman L, Tornos C, Huzjan R, Bartella L, Morris EA,

Dershaw DD. Is surgical excision warranted after benign,

concordant diagnosis of papilloma at percutaneous breast biopsy?

AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006;186:1328-34. Crossref

29. MacColl C, Salehi A, Parpia S, Hodgson N, Ramonas M,

Williams P. Benign breast papillary lesions diagnosed on core

biopsy: upgrade rate and risk factors associated with malignancy

on surgical excision. Virchows Arch. 2019;475:701-7. Crossref

30. Jung SY, Kang HS, Kwon Y, Min SY, Kim EA, Ko KL, et al.

Risk factors for malignancy in benign papillomas of the breast

on core needle biopsy. World J Surg. 2010;34:261-5. Crossref

31. Rizzo M, Linebarger J, Lowe MC, Pan L, Gabram SG, Vasquez

L, et al. Management of papillary breast lesions diagnosed on

core-needle biopsy: clinical pathologic and radiologic analysis of

276 cases with surgical follow-up. J Am Coll Surg. 2012;214:280-7. Crossref

32. Glenn ME, Throckmorton AD, Thomison JB 3rd, Bienkowski RS.

Papillomas of the breast 15 mm or smaller: 4-year experience in

a community-based dedicated breast imaging clinic. Ann Surg

Oncol. 2015;22:1133-9. Crossref