Tenosynovial Giant Cell Tumour of the Temporomandibular Joint with Initial Suspicion of Nodal Metastases: A Case Report

CASE REPORT

Hong Kong J Radiol 2024 Dec;27(4):e237-41 | Epub 18 November 2024

Tenosynovial Giant Cell Tumour of the Temporomandibular Joint with Initial Suspicion of Nodal Metastases: A Case Report

LY Lam1, WL Wong1, KWS Ko1, ZCS Tsang2, KM Chu1

1 Department of Radiology and Imaging, Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

2 Department of Pathology, Kwong Wah Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

Correspondence: Dr LY Lam, Department of Radiology and Imaging, Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China. Email: lly858@ha.org.hk

Submitted: 19 September 2023; Accepted: 10 January 2024.

Contributors: LYL and WLW designed the study. All authors acquired and analysed the data. LYL and WLW drafted the manuscript. All

authors critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study,

approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Funding/Support: This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data Availability: All data generated or analysed during the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: The study was approved by the Kowloon Central Cluster and Kowloon East Cluster Research Ethics Committee of Hospital Authority, Hong Kong (Ref No.: KC/KE-28-0056/ER-1). The requirement for patient consent was waived by the Committee due to loss to

follow-up of the patient and the use of de-identified information of the patient in the study.

CASE PRESENTATION

A 26-year-old female with good past health presented

with 1-month history of progressive swelling at the left

preauricular region. Physical examination revealed a

4-cm mass over the left preauricular region, not fixed to

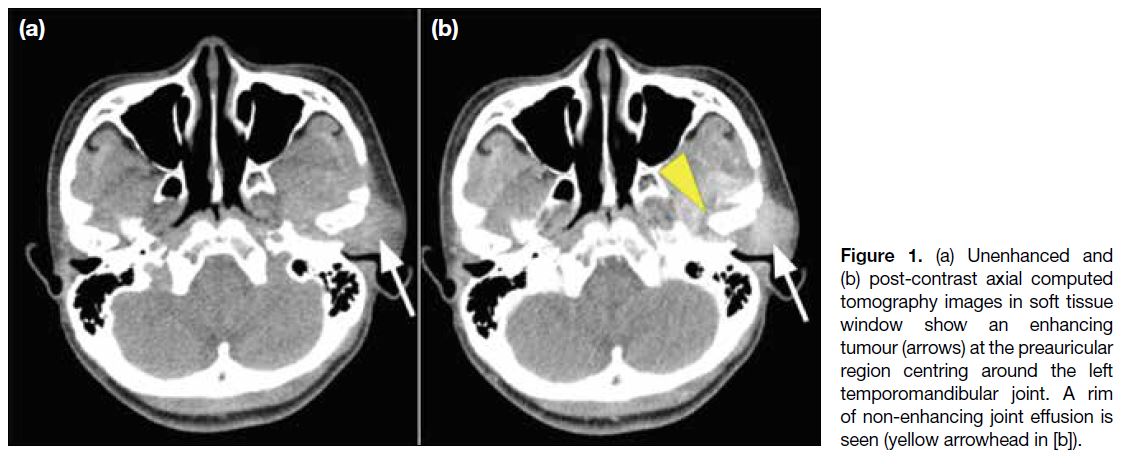

the underlying structures. Computed tomography (CT)

demonstrated a 5-cm hyperdense and heterogeneously

enhancing soft tissue mass at the left preauricular region

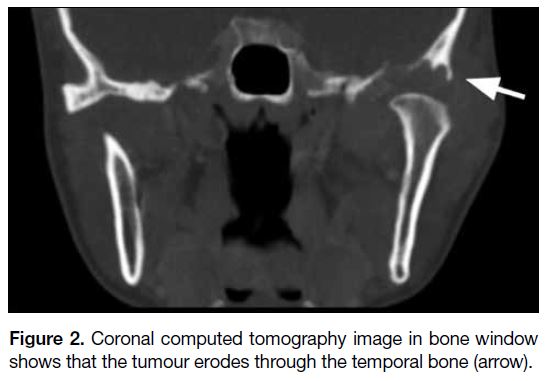

(Figure 1). There was bony erosion of the left mandibular

head and articular tubercle of the temporal bone with

extension to the base of the middle cranial fossa (Figure 2). No parenchymal invasion of the left temporal lobe

was observed. Differential diagnoses included an

aggressive parotid tumour with bony extension or an

aggressive bone condition arising from the temporal

bone such as osteomyelitis or metastasis or primary bone

tumours such as aneurysmal bone cyst.

Figure 1. (a) Unenhanced and

(b) post-contrast axial computed tomography images in soft tissue window show an enhancing tumour (arrows) at the preauricular region centring around the left temporomandibular joint. A rim of non-enhancing joint effusion is seen (yellow arrowhead in [b]).

Figure 2. Coronal computed tomography image in bone window shows that the tumour erodes through the temporal bone (arrow).

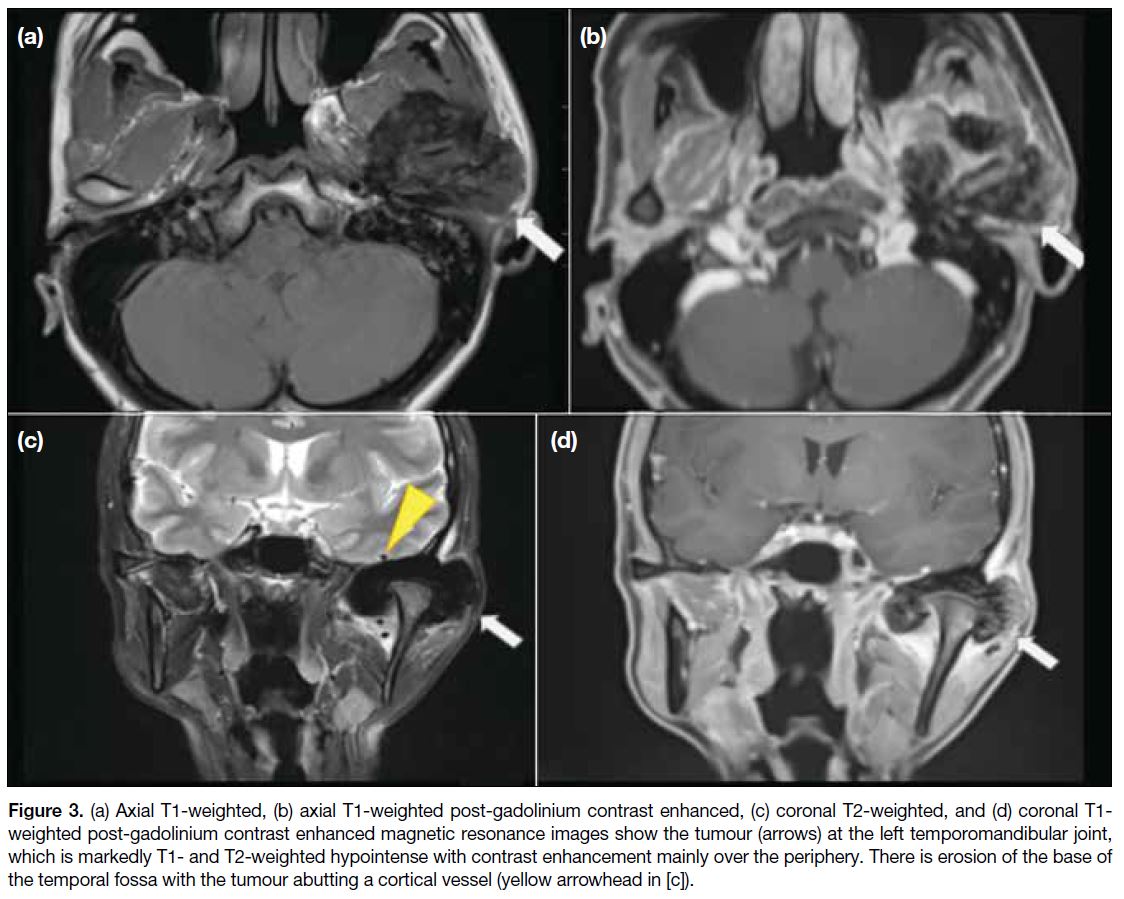

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed an

expansile and lobulated mass with T1- and T2-weighted

hypointense signals and moderate contrast enhancement centring at the left temporomandibular joint (TMJ)

[Figure 3] and indenting the left middle cranial fossa dura

superiorly. There was involvement of the left mandibular

condyle and superficial lobe of the left parotid gland.

Several nodules showing similar signal characteristics to

the index lesion were seen within the left parotid gland.

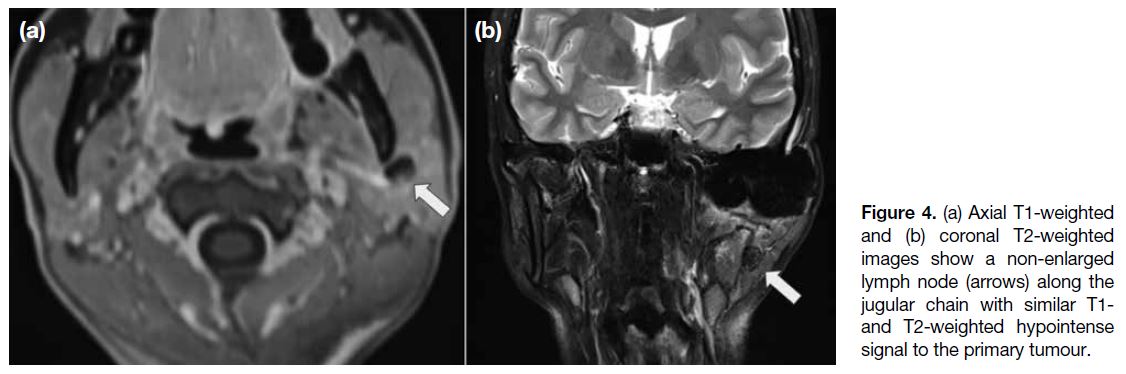

A few lymph nodes were seen along the left jugular

chain (Figure 4), with similar signal characteristics.

These were suspicious of nodal metastases. Biopsy of

the mass revealed mononuclear cells with osteoclast-type

giant cells, presence of hemosiderin pigment and

expression of clusterin and D2-40 via immunostaining.

Features were compatible with diffuse-type tenosynovial

giant cell tumour (TGCT).

Figure 3. (a) Axial T1-weighted, (b) axial T1-weighted post-gadolinium contrast enhanced, (c) coronal T2-weighted, and (d) coronal T1-weighted post-gadolinium contrast enhanced magnetic resonance images show the tumour (arrows) at the left temporomandibular joint, which is markedly T1- and T2-weighted hypointense with contrast enhancement mainly over the periphery. There is erosion of the base of the temporal fossa with the tumour abutting a cortical vessel (yellow arrowhead in [c]).

Figure 4. (a) Axial T1-weighted

and (b) coronal T2-weighted images show a non-enlarged lymph node (arrows) along the jugular chain with similar T1-and T2-weighted hypointense signal to the primary tumour.

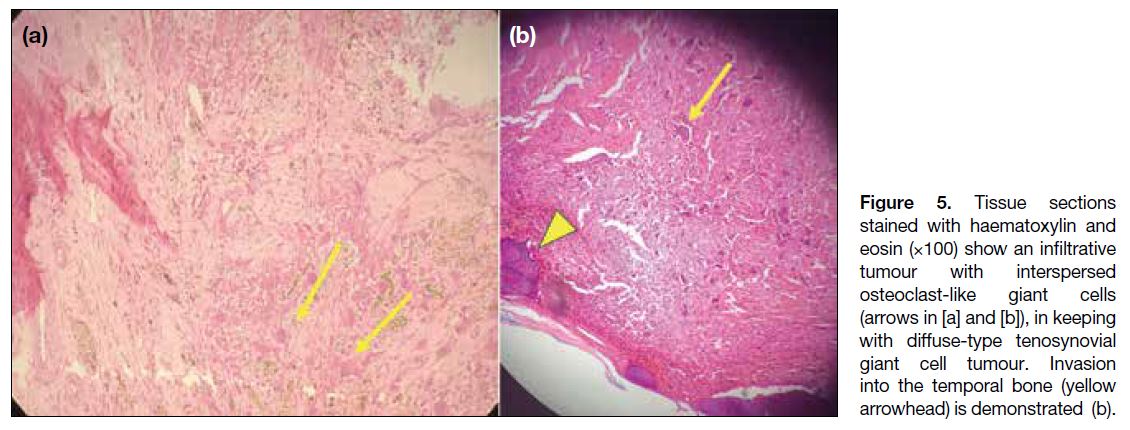

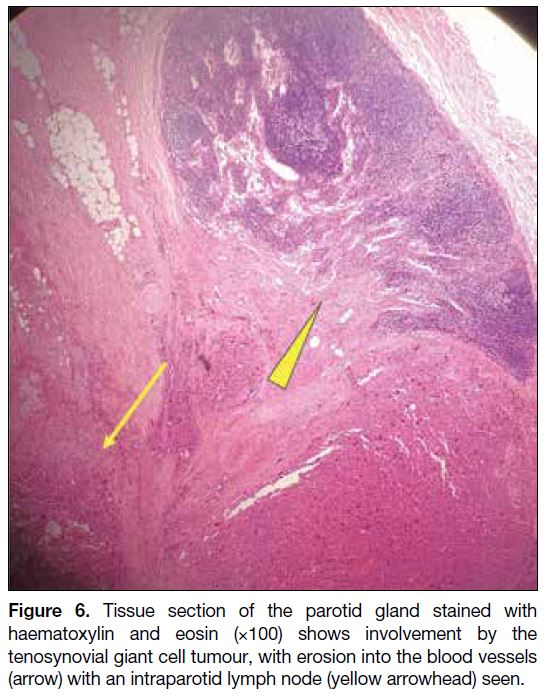

Wide local excision and cervical lymph node dissection

were performed. Final pathology of the specimen

confirmed local involvement including the mandibular

fossa of the temporal bone (Figure 5), mandibular

condyle, zygoma, left parotid gland (Figure 6), and dura

at the left temporal fossa. No malignant cells were seen. Cervical lymph nodes from the jugular chain showed

hemosiderin laden macrophages without giant cells or

malignant cells.

Figure 5. Tissue sections

stained with haematoxylin and eosin (×100) show an infiltrative tumour with interspersed osteoclast-like giant cells (arrows in [a] and [b]), in keeping with diffuse-type tenosynovial giant cell tumour. Invasion into the temporal bone (yellow arrowhead) is demonstrated (b).

Figure 6. Tissue section of the parotid gland stained with haematoxylin and eosin (×100) shows involvement by the tenosynovial giant cell tumour, with erosion into the blood vessels

(arrow) with an intraparotid lymph node (yellow arrowhead) seen.

In view of the positive surgical margins, the patient

underwent postoperative adjuvant radiotherapy of 40 Gy

in 20 fractions. There have been no signs of recurrence

on clinical and imaging follow-up by MRI 6 months

post-operation.

DISCUSSION

TGCT encompasses a group of neoplasms arising

from the synovial membranes of the joints, bursae, or

tendons. Previously diffuse TGCTs were well known

as pigmented villonodular synovitis. This term is no

longer recommended by the World Health Organization3

as the suffix -itis may wrongly imply an inflammatory

condition.

Most TGCTs are benign. Malignant TGCT is exceedingly

rare, with only 50 reported cases worldwide, typically

affecting the lower extremities and most affected adults

aged 50 to 60 years.[1]

The aetiology of TGCTs is largely unknown. Some

studies attribute the process to repeated intra-articular

haemorrhage following trauma, whereas some proposed

that it is due to disturbed lipid metabolism.[2] The patient

in our case had good past health with no history of facial

trauma.

TGCTs are classified according to their location

(intra-articular vs. extra-articular) and growth pattern

(localised vs. diffuse). There is no sex predilection for

intra-articular disease, while there is a slight female

predilection for extra-articular disease.[3] The clinical

presentation and affected joints differ between localised

and diffuse subtypes. Localised TGCTs involve part of

the synovium and are commonly found in the fingers.3

Patients typically present in their 3rd to 5th decade with a

female predilection. The second most common location

is the hand and wrist regions. They often present as

painless and slow growing masses.[4] Diffuse TGCTs are

less common with an annual incidence of 4 per million

population. These are monoarticular diseases affecting

large joints, typically the knees and hips, accounting

for 66% to 80% and 4% to 16% of cases, respectively.[1]

Other joints such as the ankles, shoulders, and elbows

are affected in descending order of frequency.[1] [3] Patients

are commonly in their early middle age. Patients with

diffuse TGCTs present with painful joint swelling with

reduced range of movement. Haemarthrosis is commonly encountered. This is a locally aggressive lesion that tends

to have local recurrence following complete excision,

with a reported recurrence rate of 35%.[1] [3]

TGCT of the TMJ is rare and is typically the diffuse

form. The first case of TGCT involving the TMJ was

reported in 1973.[5] To date, around 100 cases have been reported worldwide.[6] The most common presentation

is of a preauricular mass. Some cases may present with

limited range of movement at the TMJ. Because of

their close proximity to the parotid gland, they are often

mistaken for parotid lesions.[7]

Microscopically, TGCTs have a variable appearance,

consisting of variable proportions of multinucleated giant cells, foamy macrophages, haemosiderin, and stromal collagenisation.

Radiographs of diffuse intra-articular TGCTs commonly

demonstrate joint effusion, soft tissue swelling and

extrinsic pressure erosion of bone, usually involving

both sides of a joint. Radiographs may appear normal in

21% of cases.[3]

On CT and MRI, other than erosion and joint effusion,

extensive synovial thickening with villous or nodular

projections extending into the joint can be seen. These

synovial thickening and masses are hyperdense on CT

due to their high iron content. On MRI, they appear

hypointense on T1- and T2-weighted sequences due to

hemosiderin deposition.[1] [7] These were well illustrated

in our case. Blooming artefacts are pathognomonic

for TGCTs. These tumours show predominantly high

signals in short-tau inversion recovery sequence.[7]

Contrast enhancement is observed due to their significant

vascularity.[3]

Sonographic findings are less specific for the diffuse

intra-articular subtype of TGCTs and include complex

heterogeneous echogenic masses along the thickened

hypoechoic synovium and joint effusion.[3] Doppler

imaging commonly reveals increased blood flow.

TGCTs show hypermetabolism on fluorine-18

fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography with

an average standard uptake value of 5.9.[3] This may be a

potential pitfall for a misdiagnosis of malignant tumour.

In our case, the CT and MRI demonstrated significant involvement of both sides of the TMJ by the TGCTs,

with more erosive effect on the mandibular fossa side

than that of the mandibular condyle. This leads to the

false impression that the disease is bony in origin.

The characteristic magnetic resonance features of

hemosiderin deposition were helpful in making the

correct diagnosis.

Both malignant TGCTs and TGCTs of the TMJ are very

rare conditions; only a few cases of malignant TGCTs

of the TMJs have been reported in the literature.[6] By

imaging alone, it is difficult to differentiate benign

from malignant TGCTs. Features such as rapid growth,

aggressive bone destruction, and evidence of distant

metastases should raise suspicion of a malignant nature.[5]

Common metastatic sites of malignant TGCTs are the

regional lymph nodes, lungs, and spine.

In our case, multiple lymph nodes with similar

hypointense signals to the index lesion were found, raising

an initial suspicion of nodal metastases. Nonetheless the

pathology of the index tumour and lymph nodes showed

no malignant cells.

A few cases of metastatic spread of benign TGCTs

have been described.[8] The presentation of metastases

occurred in longer time spans after the initial diagnosis,

from years to decades. In our case, the discovery of

suspicious lymph nodes was within 1 month of the

initial symptoms. The histological findings of the lymph

nodes did not meet the criteria for metastases from

TGCTs described in the case report by Malik et al.[9]

These rendered the possibility of true nodal metastases

less likely. The histological findings of haemosiderin

laden macrophages and the imaging findings of the

lymph nodes can be due to lymphatic drainage of

degraded blood products from the haemorrhagic tumour,

which has been reported in chronic cases of tumoural

haemorrhage.[10] Our findings suggest that imaging alone

is not definitive for the diagnosis of nodal metastases

and pathology remains the gold standard. Nevertheless

clinicians should be vigilant for metastasis in patients

with known diffuse TGCTs who present with palpable

lymph nodes since benign TGCTs can metastasise and

recur after definitive treatment.[8]

The mainstay of treatment for TGCTs is surgical excision

with wide margin. Aggressive cases with a high chance

of recurrence will benefit from postoperative radiation

therapy.[11] In view of the positive surgical margins in the surgical specimen, postoperative radiation and long-term

follow-up will be beneficial to our patient to reduce the

chance of recurrence and metastases.

CONCLUSION

We report a case of TGCT of the TMJ. Such tumours

should be considered in the differential diagnoses of

preauricular aggressive swellings. Clinicians should

consider nodal metastasis in patients with diffuse TGCTs

who present with palpable lymph nodes.

REFERENCES

1. De Saint Aubain Somerhausen N, van de Rijn M; The WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board. Tenosynovial giant cell tumour. WHO Classification of Tumours Soft Tissue and Bone

Tumours, 5th ed. Lyon: IARC Press; 2020: 133-6.

2. Bemporad JA, Chaloupka JC, Putman CM, Roth TC, Tarro J, Mitra S, et al. Pigmented villonodular synovitis of the

temporomandibular joint: diagnostic imaging and endovascular

therapeutic embolization of a rare head and neck tumor. AJNR

Am J Neuroradiol. 1999;20:159-62.

3. Murphey MD, Rhee JH, Lewis RB, Fanburg-Smith JC, Flemming DJ, Walker EA. Pigmented villonodular synovitis:

radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2008;28:1493-518. Crossref

4. Peh WC, Shek TW, Ip WY. Growing wrist mass. Ann Rheum Dis. 2001;60:550-3. Crossref

5. Yoon HJ, Cho YA, Lee JI, Hong SP, Hong SD. Malignant

pigmented villonodular synovitis of the temporomandibular joint

with lung metastasis: a case report and review of the literature. Oral

Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2011;111:e30-6. Crossref

6. Verspoor FG, Mastboom MJ, Weijs WL, Koetsveld AC, Schreuder HW, Flucke U. Treatments of tenosynovial giant cell

tumours of the temperomandibular joint: a report of three cases and

a review of literature. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2018;47:1288-94. Crossref

7. Le WJ, Li MH, Yu Q, Shi HM. Pigmented villonodular synovitis of

the temporomandibular joint: CT imaging findings. Clin Imaging.

2014;38:6-10. Crossref

8. Chen EL, de Castro CM 4th, Hendzel KD, Iwaz S, Kim MA, Valeshabad AK, et al. Histologically benign metastasizing

tenosynovial giant cell tumor mimicking metastatic malignancy: a

case report and review of literature. Radiol Case Rep. 2019;14:934-40. Crossref

9. Malik K, Raja A, Shirley S. Isolated regional nodal metastasis in giant cell tumor of the bone: case report and review of literature. South Asian J Cancer. 2020;9:58. Crossref

10. Elmore SA. Histopathology of the lymph nodes. Toxicol Pathol. 2006;34:425-54. Crossref

11. Baniel C, Yoo CH, Jiang A, von Eyben R, Mohler DG, Ganjoo K,

et al. Long-term outcomes of diffuse or recurrent tenosynovial

giant cell tumor treated with postoperative external beam radiation

therapy. Pract Radiat Oncol. 2023;13:e301-7. Crossref