Sporadic Pulmonary Arteriovenous Malformation with a History of Stroke/Cerebrovascular Ischaemia Successfully Treated with Coil Embolisation: Two Case Reports

CASE REPORT

Hong Kong J Radiol 2023 Dec;26(4):e24-8 | Epub 7 Nov 2023

Sporadic Pulmonary Arteriovenous Malformation with a History of Stroke/Cerebrovascular Ischaemia Successfully Treated with Coil Embolisation: Two Case Reports

KO Cheung, CY Cheung, SW Sim, PSF Lee

Department of Radiology, North District Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

Correspondence: Dr KO Cheung, Department of Radiology, North District Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China. Email: cko398@ha.org.hk

Submitted: 5 Mar 2022; Accepted: 6 Nov 2022.

Contributors: All authors designed the study. KOC and SWS acquired and analysed the data. KOC drafted the manuscript. All authors critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Funding/Support: This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data Availability: All data generated or analysed during the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: This study was conducted in accordance with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from the patients for the purpose of the study.

CASE PRESENTATIONS

Case 1

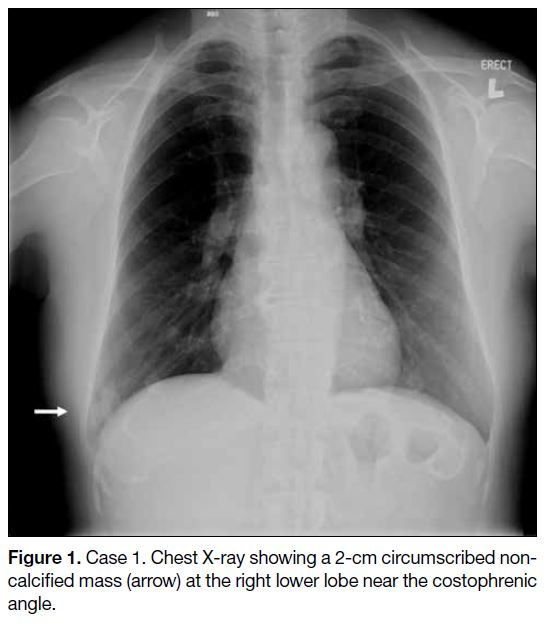

A 64-year-old female, who had been a chronic smoker

for 47 years smoking one to five cigarettes per day, had

a history of ischaemic stroke at the age of 39. In 2019,

she was referred to the medical outpatient clinic of our

institution due to a 2-month history of cough, and a chest

X-ray revealed an incidental finding of a 2-cm opacity

at the right lower zone (Figure 1). Subsequent contrast

computed tomography (CT) of the thorax revealed a

2-cm avid arterial-enhancing lesion at the right lower

lobe near the costophrenic angle, corresponding to a

previous chest radiograph–detected lesion. With the

presence of a single hypertrophic tortuous pulmonary

artery supply and single hypertrophic early draining

pulmonary vein (Figure 2), a diagnosis of pulmonary

arteriovenous malformation (PAVM) was made.

Figure 1. Case 1. Chest X-ray showing a 2-cm circumscribed noncalcified mass (arrow) at the right lower lobe near the costophrenic angle.

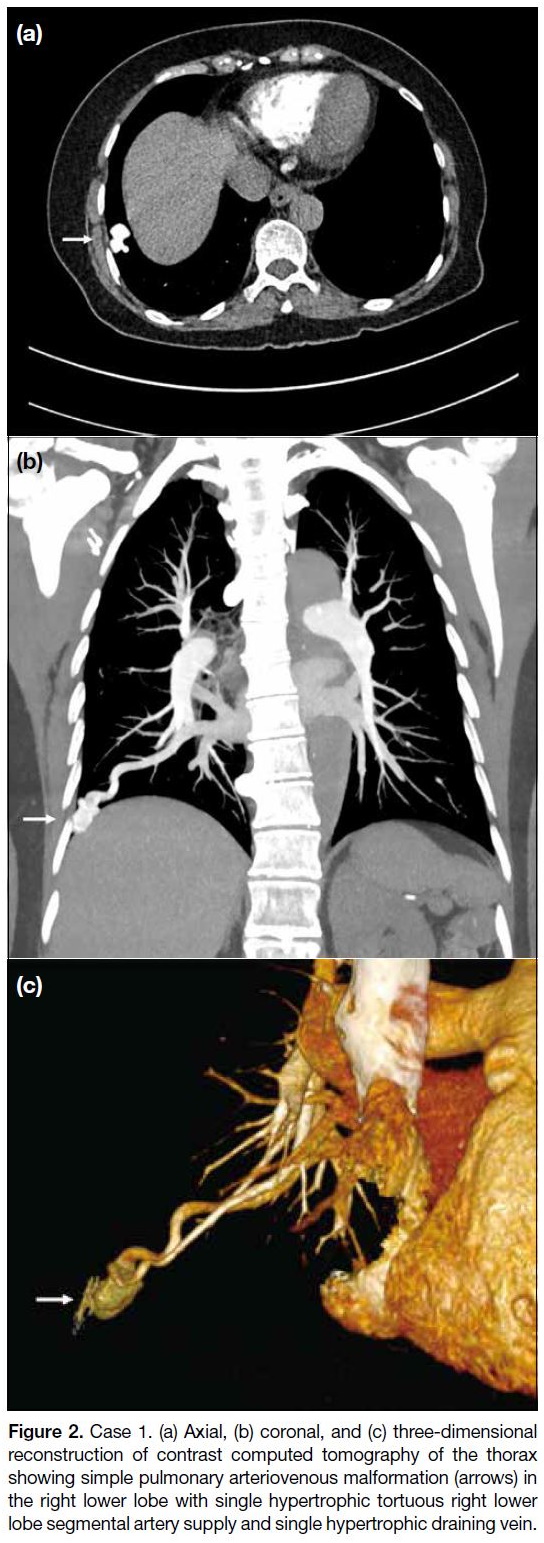

Figure 2. Case 1. (a) Axial, (b) coronal, and (c) three-dimensional

reconstruction of contrast computed tomography of the thorax

showing simple pulmonary arteriovenous malformation (arrows) in

the right lower lobe with single hypertrophic tortuous right lower

lobe segmental artery supply and single hypertrophic draining vein.

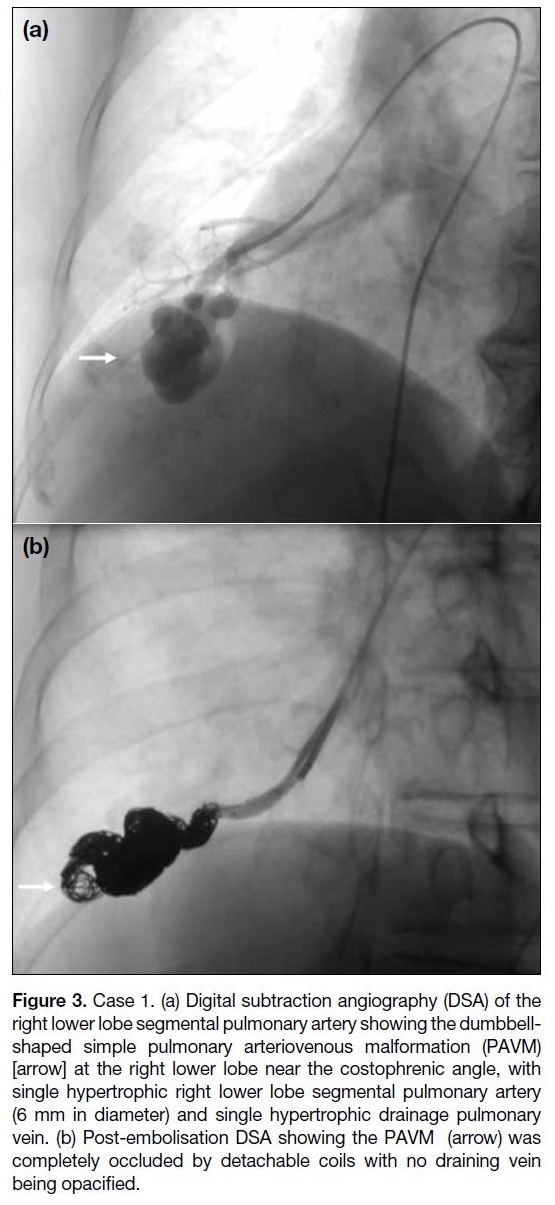

The patient was treated with coil embolisation to the

PAVM in the right lower lobe, performed via a right antegrade common femoral vein approach. The right

lower lobe pulmonary artery was cannulated with

a 5-Fr multipurpose angiographic (MPA) catheter

(Cordis Corporation, Miami Lakes [FL], US). Digital

subtraction angiography (DSA) showed a dumbbell-shaped

simple PAVM with single hypertrophic right

lower lobe segmental pulmonary artery (6 mm in

diameter) and single hypertrophic draining right lower lobe pulmonary

vein (Figure 3a). The PAVM was selectively cannulated

with a 3-Fr Rebar Reinforced Microcatheter (Micro

Therapeutics Inc, Irvine [CA], US) through the 5-Fr

MPA catheter, and coil embolisation was performed

with 28 detachable coils (EV3 Concerto detachable

coils; Micro Therapeutics Inc, Irvine [CA], US). Post-embolisation

DSA revealed complete occlusion of the

PAVM (Figure 3b). No complication was encountered

and the patient was discharged home on the day of the

procedure. Nonetheless she defaulted her follow-up 2

months after embolisation.

Figure 3. Case 1. (a) Digital subtraction angiography (DSA) of the

right lower lobe segmental pulmonary artery showing the dumbbell-shaped

simple pulmonary arteriovenous malformation (PAVM)

[arrow] at the right lower lobe near the costophrenic angle, with

single hypertrophic right lower lobe segmental pulmonary artery

(6 mm in diameter) and single hypertrophic drainage pulmonary

vein. (b) Post-embolisation DSA showing the PAVM (arrow) was

completely occluded by detachable coils with no draining vein

being opacified.

Case 2

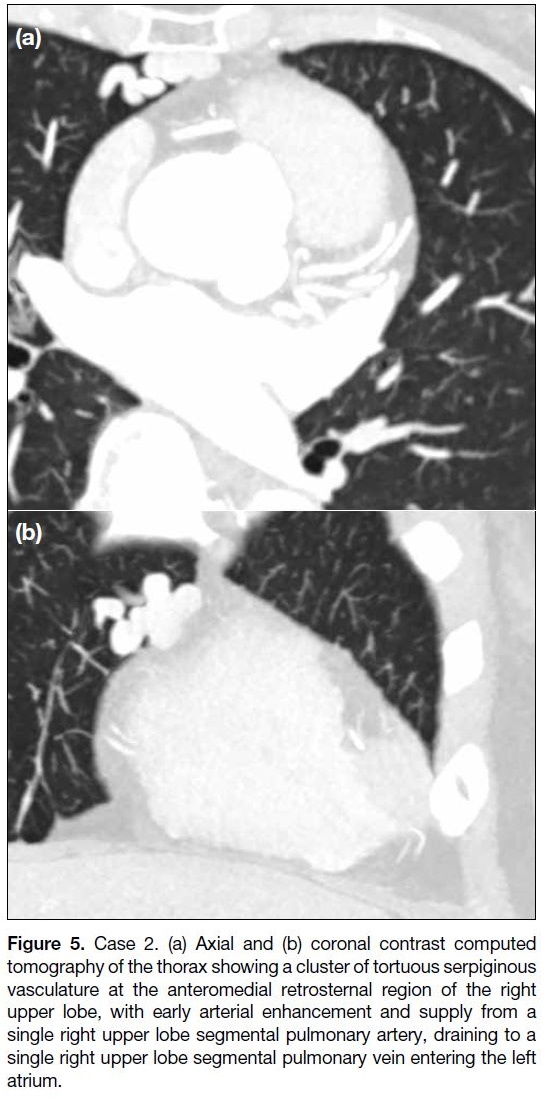

A 73-year-old female with controlled hypertension

was referred to the medical outpatient clinic of our

institution in 2019 for non-exertional chest pain. She

had a history of transient ischaemic attack at the age

of 64. Chest radiograph was unremarkable (Figure 4).

CT coronary angiogram incidentally revealed a cluster

of tortuous serpiginous vasculature at the anteromedial

retrosternal region of the right upper lobe, suspicious

of PAVM. Contrast CT of the thorax subsequently

confirmed this diagnosis (Figure 5).

Figure 4. Case 2. Chest radiograph was unremarkable. No focal

lung mass lesion was seen.

Figure 5. Case 2. (a) Axial and (b) coronal contrast computed

tomography of the thorax showing a cluster of tortuous serpiginous

vasculature at the anteromedial retrosternal region of the right

upper lobe, with early arterial enhancement and supply from a

single right upper lobe segmental pulmonary artery, draining to a

single right upper lobe segmental pulmonary vein entering the left

atrium.

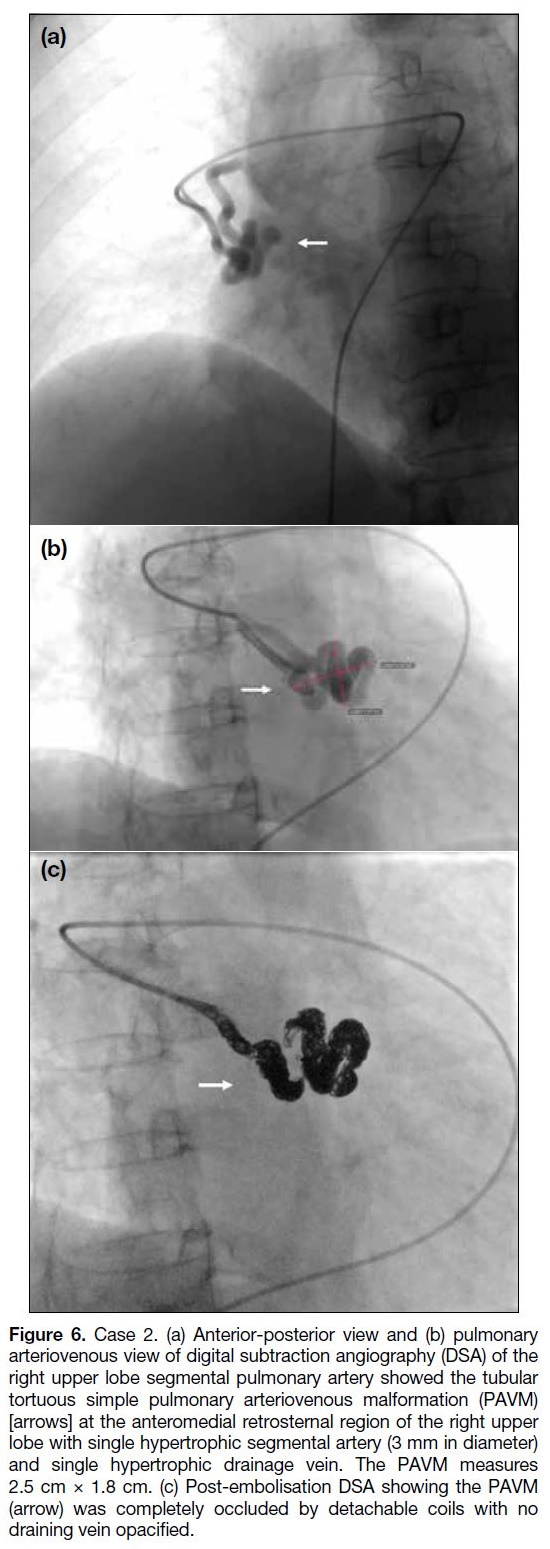

The patient underwent coil embolisation to the PAVM in

the right upper lobe via a right antegrade common femoral

vein approach. The right upper lobe pulmonary artery

was cannulated with a 5-Fr MPA catheter. DSA showed

a 2.5 cm × 1.8 cm simple PAVM at the anteromedial

retrosternal region of the right upper lobe (Figure 6a and b). The PAVM was selectively cannulated with a 3-Fr

microcatheter through the 5-Fr MPA catheter, and coil

embolisation was performed with 21 detachable coils

(EV3 Concerto detachable coils).

Figure 6. Case 2. (a) Anterior-posterior view and (b) pulmonary

arteriovenous view of digital subtraction angiography (DSA) of the

right upper lobe segmental pulmonary artery showed the tubular

tortuous simple pulmonary arteriovenous malformation (PAVM)

[arrows] at the anteromedial retrosternal region of the right upper

lobe with single hypertrophic segmental artery (3 mm in diameter)

and single hypertrophic drainage vein. The PAVM measures

2.5 cm × 1.8 cm. (c) Post-embolisation DSA showing the PAVM

(arrow) was completely occluded by detachable coils with no

draining vein opacified.

Post-embolisation DSA showed complete occlusion of

the PAVM (Figure 6c). No complication was encountered

and the patient was discharged home the next day. At

2-month follow-up, she remained asymptomatic and

had no exertional shortness of breath, ankle oedema or

haemoptysis. Follow-up radiological imaging was still

pending.

DISCUSSION

PAVM is a rare disease. It is a high-flow low-resistance

fistulous communication between the pulmonary artery

and pulmonary vein without interposition of a capillary

bed. Limited prevalence data suggest that PAVM

may affect up to 1 in 2600 individuals.[1] [2] The majority

(80%-90%) of PAVMs are congenital with concomitant

hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT), while the rest are sporadic. Sporadic PAVM is rarely reported

in the literature. According to Albitar et al,[3] sporadic

PAVMs occur more commonly in females, are most

often simple and single, have lower lobe predominance, and are associated with a high rate of neurological

complications. For our two patients, they had no

recurrent spontaneous epistaxis, mucosal telangiectasia

or family history of HHT, but with only visceral AVM.

Therefore, they had fewer than two of four Curaçao

diagnostic criteria, making HHT unlikely. They were

thus considered sporadic PAVM.

A PAVM can be asymptomatic or present with right-to-

left shunt symptoms, including dyspnoea, cyanosis,

haemoptysis and polycythaemia. The classic triad of dyspnoea on exertion, cyanosis, and clubbing should

alert the clinician to the possibility of a PAVM. Untreated

PAVMs can cause complications such as stroke, brain

abscess, rupture causing haemoptysis or haemothorax.

Both our patients had a history of stroke/cerebrovascular

ischaemia.

The preferred treatment for most patients with PAVM

is transcatheter embolisation. This has largely replaced

surgery because of its minimal invasiveness and short

recovery time. Surgical resection is reserved for PAVMs

not amenable to embolisation.

Treatment of PAVM can help prevent cerebral

complications such as transient ischaemic attack, stroke

or brain abscess; it can also help prevent pulmonary

complications such as lung haemorrhage, or decline in

exercise tolerance. A general rule may be to treat PAVMs

with feeding arteries >3 mm although more dedicated

centres will offer intervention when the feeding artery

exceeds 2 mm.[4] Nevertheless intervention is obviously

indicated when patients are symptomatic or when the

PAVM is enlarging.

A Grollman catheter is a right-angled pigtail catheter

with the curve on the reverse side of the angle. This

shape is most ideal to navigate through the heart or

to perform pulmonary angiogram. A reverse curve

catheter such as the Omni Flush catheter can also be

used to navigate through the right heart, but subsequent

exchange to an appropriate catheter for intervention is

needed. A steerable guiding sheath is another option. As

these catheters were not available at our centre, a 5-Fr

MPA catheter was used and we were able to successfully

navigate through the heart.

In DSA, we measure the diameter of arteriovenous

malformation to determine coil or plug size. An

undersized device should be avoided due to the risk of

distal migration. We may oversize the coil or plug by

20% to 50% relative to the feeding vessel.

The choice of embolic agents includes detachable

metallic coils, Amplatzer plug occluding device and

microvascular plug (MVP). Detachable metallic coils

enable more precise control. Coils should not be placed

directly into a PAVM because of the risk of paradoxical

coil embolisation. Instead, the tip of the coil should be

placed in a small side branch proximal to the target.

This allows it to prolapse into the feeding vessel. For

an Amplatzer plug occluding device, an appropriately sized sheath is placed into the feeding vessel and the

device is introduced via the sheath to the feeding vessel

proximal to the target. After confirming the position with

angiography, the device can be deployed by retracting

the sheath. For MVP, the MVP-5 system is advanced

into the feeding artery and the MVP plug is unsheathed

to occlude the target vessel. The position is confirmed by

selective angiogram with contrast injected via the rotator

haemostatic valve, followed by deployment of the MVP

using the detachment system.

Our patients were treated with detachable metallic coils. Heparin was given during the procedure to minimise the

risk of periprocedural paradoxical emboli, estimated at 1%.[4]

Complications of embolisation of PAVM are classified

as immediate, early or late. Immediate complications

include vascular injury and cardiac arrhythmia, but these

are rare. Air embolism is becoming rarer, probably due to

advances in technique and equipment. Precaution is also

taken to double-flush all catheters to avoid air bubbles and

clots. To avoid the complication of catheter entrapment

in a heart valve, extra care should be exercised when

withdrawing the catheter along the guidewire passing via

the heart valve post-embolisation. Pleurisy is considered

the most common early complication, occurring in up to

13% to 31% of patients.[5] It is usually self-limiting. Other

rarer early complications include pulmonary infarcts

and migration of embolic material. Late complications

include recanalisation and growth of new feeding arteries

due to collateralisation.[6] For both patients, they had no

post-embolisation complication detected.

After treatment of PAVMs, patients require long-term

follow-up imaging, preferably with a baseline scan 3 to

6 months after treatment to check if there is successful

sac involution. Follow-up imaging every 3 to 5 years

is necessary to capture any late collateralisation or recanalisation.[4]

CONCLUSION

Sporadic PAVM is rare and unlike congenital PAVM,

it is not associated with HHT. With embolisation being

minimally invasive and enabling faster recovery, it has

replaced surgery as the first-line treatment. We present

two cases of sporadic PAVM in middle-aged women with

a history of cerebrovascular accident. Both patients had

a single pulmonary artery supply and single pulmonary

vein drainage, and they were treated successfully with

coil embolisation without immediate complications.

REFERENCES

1. Shovlin CL, Condliffe R, Donaldson JW, Kiely DG, Wort SJ; British Thoracic Society. British Thoracic Society Clinical Statement on Pulmonary Arteriovenous Malformations. Thorax. 2017;72:1154-63. Crossref

2. Nakayama M, Nawa T, Chonan T, Endo K, Morikawa S, Bando M, et al. Prevalence of pulmonary arteriovenous malformations as estimated by low-dose thoracic CT screening. Intern Med. 2012;51:1677-81. Crossref

3. Albitar HA, Segraves JM, Almodallal Y, Pinto CA, De Moraes AG, Iyer VN. Pulmonary arteriovenous malformations in non-hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia patients: an 18-year retrospective study. Lung. 2020;198:679-86. Crossref

4. Trerotola SO, Pyeritz RE. PAVM embolization: an update. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2010;195:837-45. Crossref

5. Gossage JR, Kanj G. Pulmonary arteriovenous malformations. A state of the art review. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;158:643-61. Crossref

6. Hsu CC, Kwan GN, Evans-Barns H, van Driel ML. Embolisation for pulmonary arteriovenous malformation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;1:CD008017. Crossref