Ruptured Cervical Radiculomedullary Artery Mycotic Aneurysm Presenting with Intracranial and Spinal Subarachnoid Haemorrhage: A Case Report

CASE REPORT

Hong Kong J Radiol 2023 Dec;26(4):266-70 | Epub 20 Nov 2023

Ruptured Cervical Radiculomedullary Artery Mycotic Aneurysm Presenting with Intracranial and Spinal Subarachnoid Haemorrhage: A Case Report

SH Liu1, NL Chan2, NR Mahboobani1, TL Poon2, WL Poon1

1 Department of Radiology and Imaging, Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

2 Department of Neurosurgery, Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

Correspondence: Dr SH Liu, Department of Radiology and Imaging, Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China. Email: lsh264@ha.org.hk

Submitted: 23 Feb 2022; Accepted: 11 Aug 2022.

Contributors: SHL, NRM and WLP designed the study. All authors acquired and analysed the data. SHL and NLC drafted the manuscript. NRM, TLP and WLP critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Funding/Support: This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data Availability: All data generated or analysed during the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: The patient was treated in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and provided verbal consent for publication.

BACKGROUND

A 64-year-old Chinese man with no significant past

medical history presented to the Accident and Emergency

Department of our institution in December 2021 with a

1-day history of headache and vomiting. He reported no

head injury, seizure or loss of consciousness. Physical

examination revealed no focal neurological deficit.

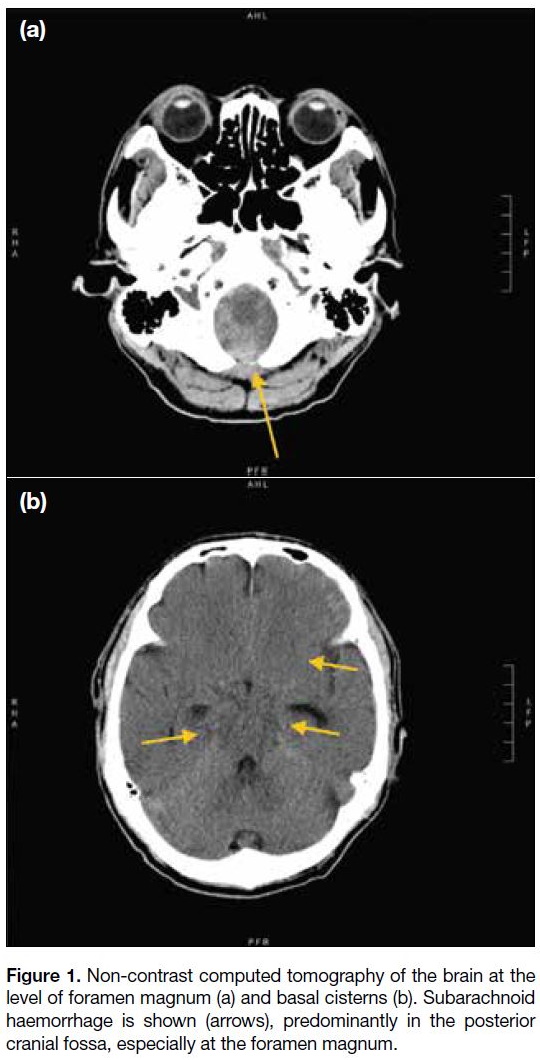

Non-contrast computed tomography (CT) of the brain

showed subarachnoid haemorrhage predominantly in

the posterior cranial fossa, extending to the spinal canal

at the C3 vertebral level, and to a lesser extent in the

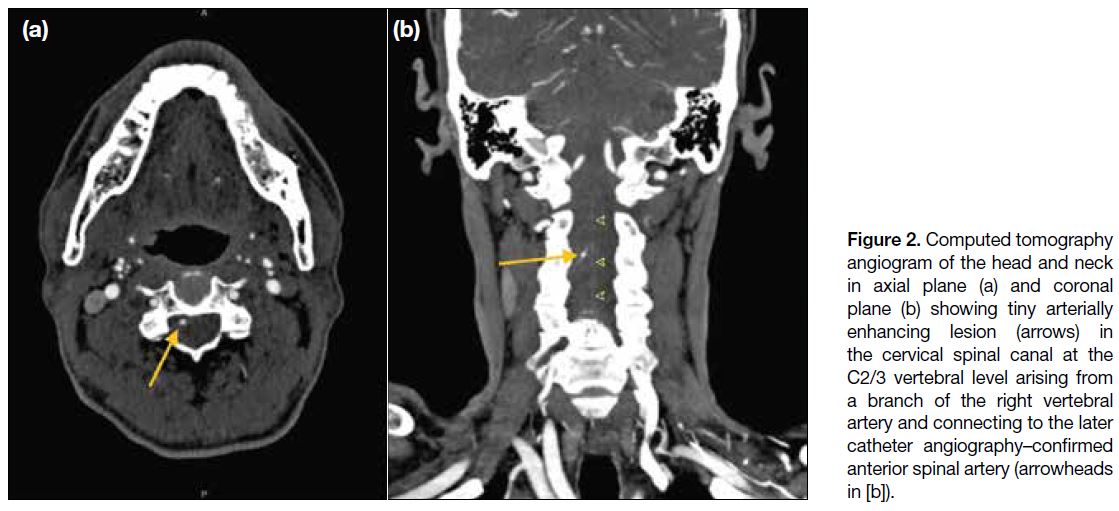

basal cisterns and at the inferior frontal regions (Figure 1). CT angiogram of the head and neck arteries revealed

a 2-mm arterial-enhancing lesion in the cervical spine

canal at the C2/3 vertebral level (Figure 2). It appeared

to arise from a branch of the right vertebral artery and

was connected to a prominent midline vasculature along

the anterior surface of the spinal cord. No intracranial

vascular lesion was identified.

Figure 1. Non-contrast computed tomography of the brain at the

level of foramen magnum (a) and basal cisterns (b). Subarachnoid

haemorrhage is shown (arrows), predominantly in the posterior

cranial fossa, especially at the foramen magnum.

Figure 2. Computed tomography

angiogram of the head and neck in axial plane (a) and coronal plane (b) showing tiny arterially enhancing lesion (arrows) in the cervical spinal canal at the C2/3 vertebral level arising from a branch of the right vertebral artery and connecting to the later catheter angiography–confirmed anterior spinal artery (arrowheads in [b]).

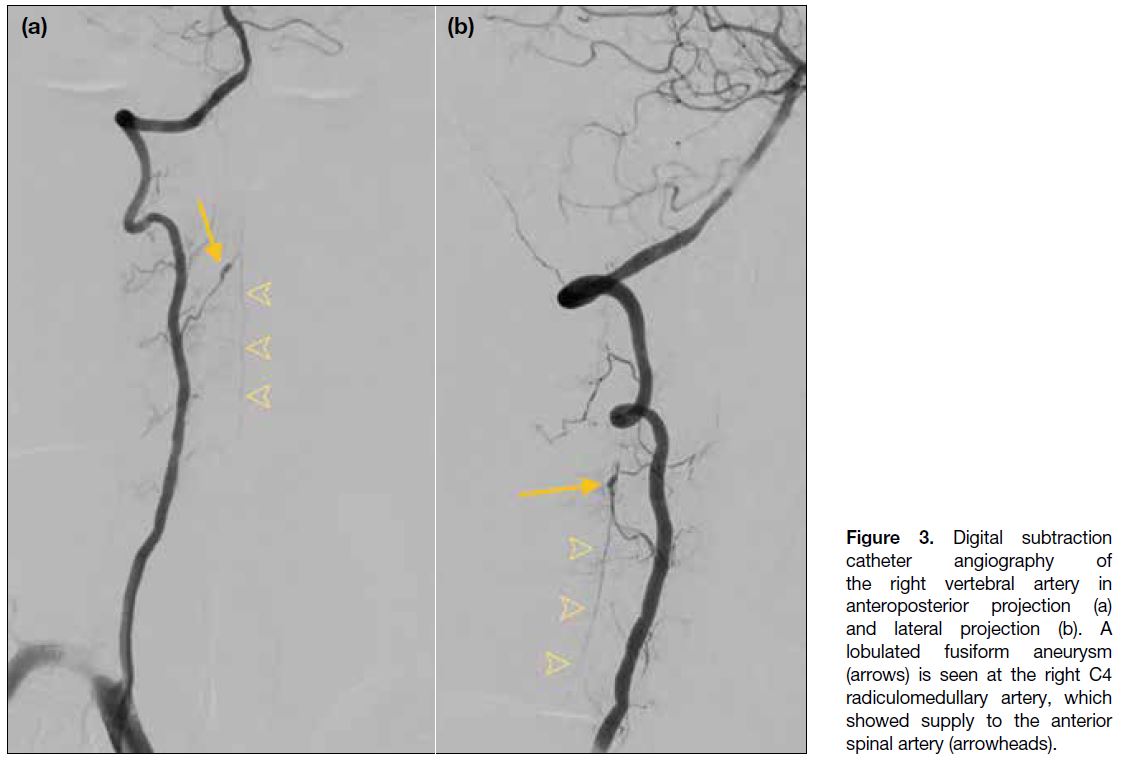

Diagnostic cerebral and cervical spine catheter

angiography was performed 3 days after admission. On right vertebral artery angiogram, there was a lobulated

fusiform aneurysm at the right C4 radiculomedullary

artery measuring 7.2 mm in length and 2.5 mm in

diameter (Figure 3). This radiculomedullary artery is

the dominant supply to the anterior spinal artery in the

cervical region and corresponds to the findings on CT

angiogram. There was no evidence of arteriovenous

shunting. Subsequent magnetic resonance imaging of

the spine revealed a contrast-enhancing lesion within

the cervical spine canal (Figure 4), corresponding to the

CT- and angiography-detected aneurysm. There was

no evidence of spinal arteriovenous shunting, vascular

malformation or tumours.

Figure 3. Digital subtraction

catheter angiography of

the right vertebral artery in

anteroposterior projection (a)

and lateral projection (b). A

lobulated fusiform aneurysm

(arrows) is seen at the right C4

radiculomedullary artery, which

showed supply to the anterior

spinal artery (arrowheads).

Figure 4. (a) Time-resolved

magnetic resonance imaging

angiography and (b) post-gadolinium

T1-weighted magnetic

resonance imaging with fat

saturation of the cervical spine.

The radiculomedullary aneurysm

(arrows) is demonstrated as an

enhancing lesion in the spinal

canal.

The patient developed fever after admission. Initial

blood tests showed normal white blood cell count but

neutrophilia. Repeated blood tests revealed leucopenia

with persistent neutrophilia, thrombocytopenia and

elevated C-reactive protein level. Blood culture

yielded Klebsiella pneumoniae species. The patient

was prescribed antibiotics. Echocardiogram showed

no evidence of myocardial infarction, endocarditis or valvular vegetation. He remained stable with no

new neurological signs or symptoms. Laboratory tests

showed subsequent normalisation of white blood cell

counts, platelet count and C-reactive protein level.

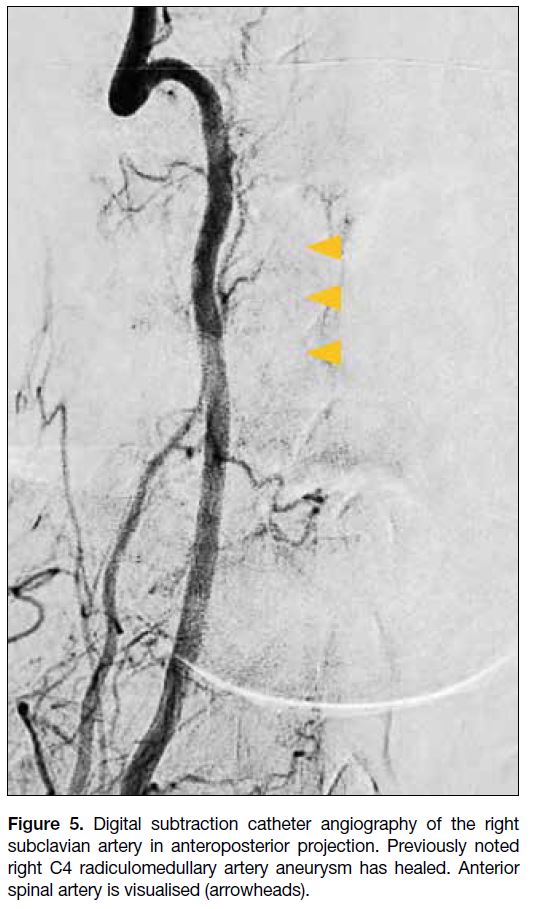

Follow-up diagnostic catheter angiography of the right

vertebral artery was performed 3 weeks after the first

catheter angiography. There was no opacification of

the aneurysm, suggesting that it is healed. The right C4

radiculomedullary artery remained patent, with supply to

the anterior spinal artery visualised (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Digital subtraction catheter angiography of the right

subclavian artery in anteroposterior projection. Previously noted

right C4 radiculomedullary artery aneurysm has healed. Anterior

spinal artery is visualised (arrowheads).

With the available clinical history, laboratory test results, and spontaneous occlusion of the aneurysm during antibiotic therapy, the most likely diagnosis for this

patient was ruptured mycotic aneurysm at the right C4

radiculomedullary artery. The patient remained stable

with neither altered consciousness nor focal neurological

deficit. He completed a 6-week course of antibiotics

as per the microbiologist’s recommendation and was

discharged uneventfully.

DISCUSSION

Spinal artery aneurysm is a rare cause of spinal or

intracranial subarachnoid haemorrhage. Diagnosis

of spinal artery aneurysms can be challenging and is

sometimes delayed due to the rarity of the condition.

These aneurysms have different morphological features

to those of intracranial origin. They are usually fusiform,

without a defined neck, and often not related to arterial

branching sites.[1] In addition, they are usually associated

with underlying vascular lesions such as arteriovenous

malformation[2] or fistula.[3] There are also reported cases

of association with tumours (e.g., haemangioblastoma),[4]

aortic coarctation2 and Moyamoya disease.[5] Other

causes include underlying vasculopathy such as

Behçet’s disease,[6] Sjögren’s syndrome,[7] systemic

lupus erythematosus,[8] and pseudoxanthoma elasticum.[9]

Mycotic aneurysms, as an alternative consideration, are

rarely reported.[1] [10]

There is no standardised treatment for ruptured

radiculomedullary artery aneurysm due to its rare

occurrence and varying aetiology.[11] [12] Management

should be tailored to each patient and take account of

the size of haematoma, size of aneurysm, neurological

symptoms, and feasibility and risk of intervention.

Vascular anatomy should be thoroughly evaluated prior

to endovascular intervention or surgery. Cross-sectional

imaging such as computed tomography or magnetic

resonance angiography and catheter angiography can

be adopted to delineate the morphology and size of the

aneurysm, size of the relevant arteries, and pattern of

vascular supply to the relevant segment of the spinal

cord.

Dabus et al[13] reported a case of spontaneous thrombosis of a posterior radiculomedullary artery dissecting aneurysm

with its parent artery in their case series, of which the

patient showed no neurological deterioration on follow-up.

This may have been due to the presence of good

anastomoses of the radiculopial and radiculomedullary

arteries. This emphasises the importance of angiographic

evaluation of the arterial supply to the spinal cord. If the culprit artery shows a dominant supply to the relevant

segment of cord, thrombosis or inadvertent injury

during intervention may jeopardise the spinal cord blood

supply. This has to be taken into account when deciding the suitable treatment strategy for each patient.

Endovascular intervention for small fusiform aneurysm

without surgical neck at a very small size vessel can be technically challenging and carries the potential risk of

arterial thrombosis causing spinal ischaemia. In the case

of large aneurysm or large haematoma with considerable

mass effect, surgery such as clipping or resection may

be a better option to reduce compression on the adjacent

spinal cord and/or nerve roots.

Cases of resolution or thrombosis of spinal artery

aneurysms have been reported,[1] [6] [7] [13] [14] [15] either with a

conservative approach or with medical treatment when

an underlying cause is determined. In cases with small

haematoma, minimal or mild neurological symptoms,

and technically challenging and high-risk intervention, a

conservative approach or medical treatment to target the

underlying cause are reasonable options.

In our patient, apart from headache and vomiting,

there was no focal neurological deficit. Aetiology

was presumed to be a mycotic aneurysm. There was

potentially high surgical risk including postoperative

neurological deterioration. Medical treatment with

antibiotic therapy was adopted.

CONCLUSION

Radiologists should remain alert for spinal artery mycotic

aneurysm as a rare cause of subarachnoid haemorrhage.

Treatment varies with the size, location and morphology

of the aneurysm, vascular anatomy of the spinal

arteries, presenting symptoms, and risk of intervention

including potential neurological deterioration. Decision

for intervention should be based on the balance of risks and benefits. In patients with mild symptoms and

high surgical risk, medical treatment with antibiotics

is a reasonable treatment choice. Follow-up imaging

including catheter angiography should be considered to

monitor progress and guide further management.

REFERENCES

1. Berlis A, Scheufler KM, Schmahl C, Rauer S, Götz F, Schumacher M. Solitary spinal artery aneurysms as a rare source of spinal subarachnoid hemorrhage: potential etiology and treatment

strategy. ANJR Am J Neuroradiol. 2005;26:405-10.

2. Rengachary SS, Duke DA, Tsai FY, Kragel PJ. Spinal arterial aneurysm: case report. Neurosurgery. 1993;33:125-9; discussion 129-30. Crossref

3. Malek AM, Halbach VV, Phatouros CC, Higashida RT, Dowd CF, Wachhorst S, et al. Spinal dural arteriovenous fistula with an associated feeding artery aneurysm: case report. Neurosurgery. 1999;44:877-80. Crossref

4. Berlis A, Schumacher M, Spreer J, Neumann HP, van Velthoven V. Subarachnoid haemorrhage due to cervical spinal cord

haemangioblastomas in a patient with von Hippel-Lindau disease.

Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2003;145:1009-13. Crossref

5. Walz DM, Woldenberg RF, Setton A. Pseudoaneurysm of the anterior spinal artery in a patient with Moyamoya: an unusual cause of subarachnoid hemorrhage. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol.

2006;27:1576-8.

6. Bahar S, Coban O, Gürvit IH, Akman-Demir G, Gökyiğit A. Spontaneous dissection of the extracranial vertebral artery with spinal subarachnoid haemorrhage in a patient with Behçet’s disease.

Neuroradiology. 1993;35:352-4. Crossref

7. Klingler JH, Gläsker S, Shah MJ, Van Velthoven V. Rupture of a spinal artery aneurysm attributable to exacerbated Sjögren syndrome: case report. Neurosurgery. 2009;64:E1010-1; discussion E1011. Crossref

8. Fody EP, Netsky MG, Mrak RE. Subarachnoid spinal hemorrhage in a case of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arch Neurol.

1980;37:173-4. Crossref

9. Kito K, Kobayashi N, Mori N, Kohno H. Ruptured aneurysm of the anterior spinal artery associated with pseudoxanthoma elasticum. Case report. J Neurosurg. 1983;58:126-8. Crossref

10. Nakamura H, Kim P, Kanaya H, Kurokawa R, Murata H, Matsuda H. Spinal subarachnoid hemorrhage caused by a mycotic aneurysm of the radiculomedullary artery: a case report and review of literature. NMC Case Rep J. 2015;2:49-52. Crossref

11. Crobeddu E, Pilloni G, Zenga F, Cossandi C, Garbossa D, Lanotte M. Dissecting aneurysm of the L1 radiculomedullary artery associated with subarachnoid hemorrhage: a case report. J Neurol Surg A Cent Eur Neurosurg. 2022;83:99-103. Crossref

12. van Es AC, Brouwer PA, Willems PW. Management considerations

in ruptured isolated radiculopial artery aneurysms. A report of two

cases and literature review. Interv Neuroradiol. 2013;19:60-6. Crossref

13. Dabus G, Tosello RT, Pereira BJ, Linfante I, Piske RL. Dissecting

spinal aneurysms: conservative management as a therapeutic

option. J Neurointerv Surg. 2018;10:451-4. Crossref

14. Yang TK. A ruptured aneurysm in the branch of the anterior spinal

artery. J Cerebrovasc Endovasc Neurosurg. 2013;15:26-9. Crossref

15. Longatti P, Sgubin D, Di Paola F. Bleeding spinal artery aneurysms.

J Neurosurg Spine. 2008;8:574-8. Crossref