Ileo-Uterine Fistula Following Endometrial Aspiration with Imaging Investigations and Hysteroscopic Correlation: A Case Report

CASE REPORT

Hong Kong J Radiol 2023 Sep;26(3):e14-8 | Epub 23 Aug 2023

Ileo-Uterine Fistula Following Endometrial Aspiration with Imaging Investigations and Hysteroscopic Correlation: A Case Report

BYK Wong1, Carina Kwa2, KM Choi2, TKK Lai3

1 Department of Radiology and Nuclear Medicine, Tuen Mun Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

2 Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Tseung Kwan O Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

3 Department of Radiology, Tseung Kwan O Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

Correspondence: Dr BYK Wong, Department of Radiology and Nuclear Medicine, Tuen Mun Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China. Email: wyk300@ha.org.hk

Submitted: 7 Apr 2022; Accepted: 5 Aug 2022.

Contributors: All authors designed the study. BYKW and CK acquired and analysed the data, drafted the manuscript, and critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Funding/Support: This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data Availability: All data generated or analysed during the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: The patient was treated in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and has provided informed consent for all procedures.

INTRODUCTION

Ileo-uterine fistula is a very rare condition sporadically

reported in the literature. Its occurrence following

endometrial sampling, which is a relatively minimally

invasive procedure, has not been reported. We present

a case of ileo-uterine fistula following endometrial

aspiration and describe its imaging features with

hysteroscopic correlation.

CASE REPORT

A 73-year-old female presented with a 2-week history

of post-menopausal brownish vaginal spotting. Physical

examination was unremarkable except for an atrophic

cervix. Transabdominal and transvaginal ultrasound

revealed a small, retroverted uterus. Endometrial

sampling with Pipelle identified chronic endometritis

and pyometra. Ultrasound examination was repeated

because of persistent foul-smelling vaginal discharge.

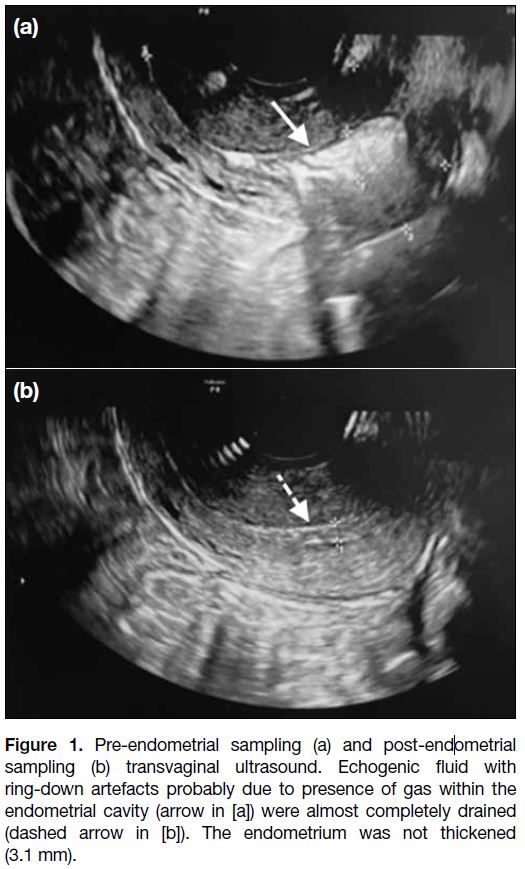

There was echogenic fluid with gaseous bubbles causing ring-down artefacts within the endometrial cavity. It was

drained by endometrial sampling and found to be pus

(Figure 1).

Figure 1. Pre-endometrial sampling (a) and post-endometrial

sampling (b) transvaginal ultrasound. Echogenic fluid with

ring-down artefacts probably due to presence of gas within the

endometrial cavity (arrow in [a]) were almost completely drained

(dashed arrow in [b]). The endometrium was not thickened

(3.1 mm).

Histology of the endometrial biopsy revealed

neutrophilic infiltrate, bacterial clumps, food particles,

intestinal epithelial fragments, and villi. There was no

evidence of malignancy. Diagnosis of pyometra was

made and perforation of uterus and/or intestinal-uterine

fistula were suspected.

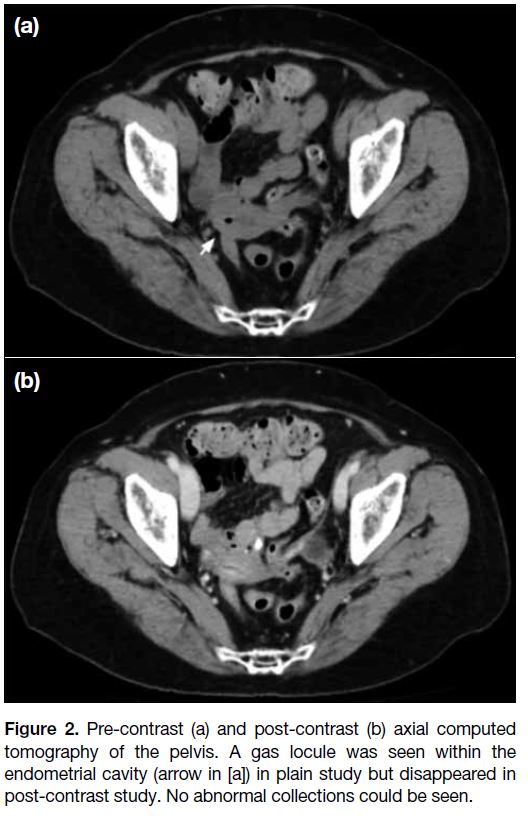

Urgent contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT)

of the pelvis revealed an atrophic uterus. Some normal-looking

small bowel loops abutted the uterus. A tiny gas

locule was noted within the endometrial cavity on pre-contrast

study (Figure 2a) but was absent on post-contrast

study (Figure 2b). No definite enterouterine fistula was

found. There was no intra-abdominal collection, active

contrast extravasation or pneumoperitoneum.

Figure 2. Pre-contrast (a) and post-contrast (b) axial computed

tomography of the pelvis. A gas locule was seen within the

endometrial cavity (arrow in [a]) in plain study but disappeared in

post-contrast study. No abnormal collections could be seen.

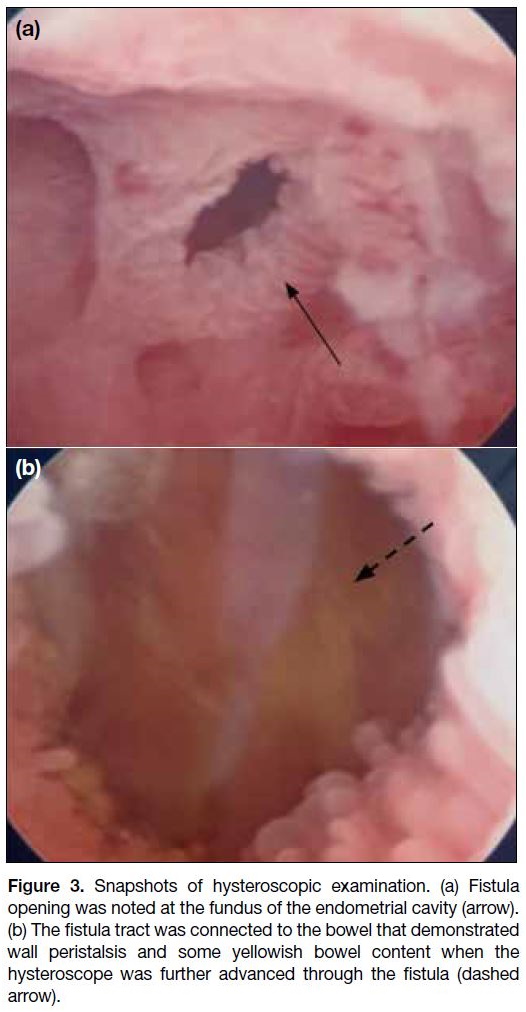

Diagnostic hysteroscopy revealed irregular and

oedematous endometrium with a 5-mm fistula opening

at the uterine fundus (Figure 3a). The hysteroscope was

able to pass through the fistula tract and enter the bowel

with bowel wall peristalsis and some yellowish bowel

content seen (Figure 3b). This confirmed the diagnosis

of enterouterine fistula, likely connecting the uterus and

the small bowel.

Figure 3. Snapshots of hysteroscopic examination. (a) Fistula

opening was noted at the fundus of the endometrial cavity (arrow).

(b) The fistula tract was connected to the bowel that demonstrated

wall peristalsis and some yellowish bowel content when the

hysteroscope was further advanced through the fistula (dashed

arrow).

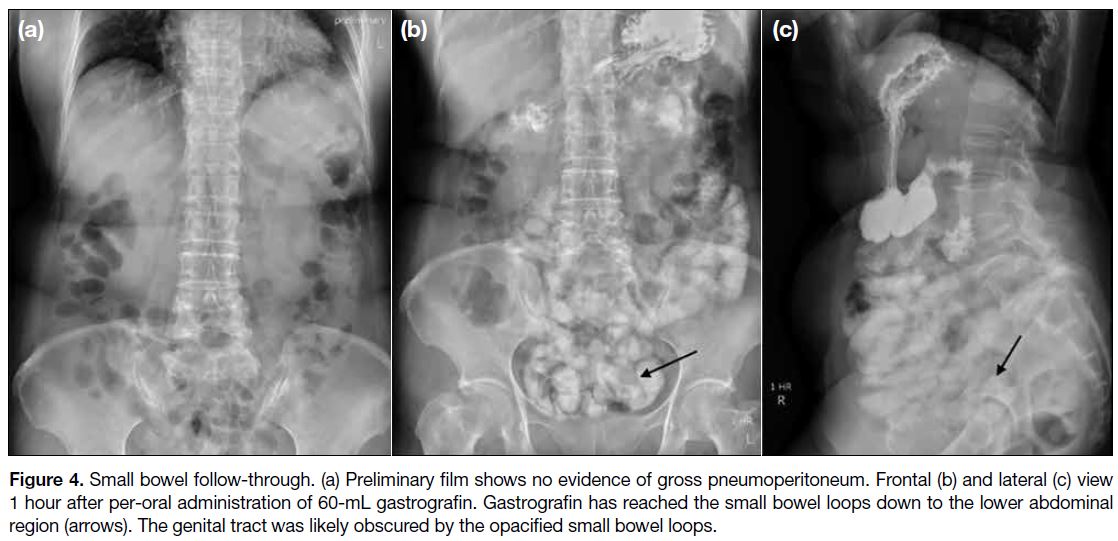

A small bowel follow-through was then arranged. The

preliminary film showed no gross pneumoperitoneum

(Figure 4a). Gastrografin reached the small bowel at

the lower abdomen on spot images taken 1 hour after

per-oral administration of gastrografin. The genital tract

was likely obscured by the opacified small bowel on

both frontal and lateral views (Figure 4b and c). The

patient complained of clear vaginal discharge 15 minutes

after the spot images, raising the clinical suspicion of

contrast material entering the genital tract via the fistula.

Figure 4. Small bowel follow-through. (a) Preliminary film shows no evidence of gross pneumoperitoneum. Frontal (b) and lateral (c) view

1 hour after per-oral administration of 60-mL gastrografin. Gastrografin has reached the small bowel loops down to the lower abdominal

region (arrows). The genital tract was likely obscured by the opacified small bowel loops.

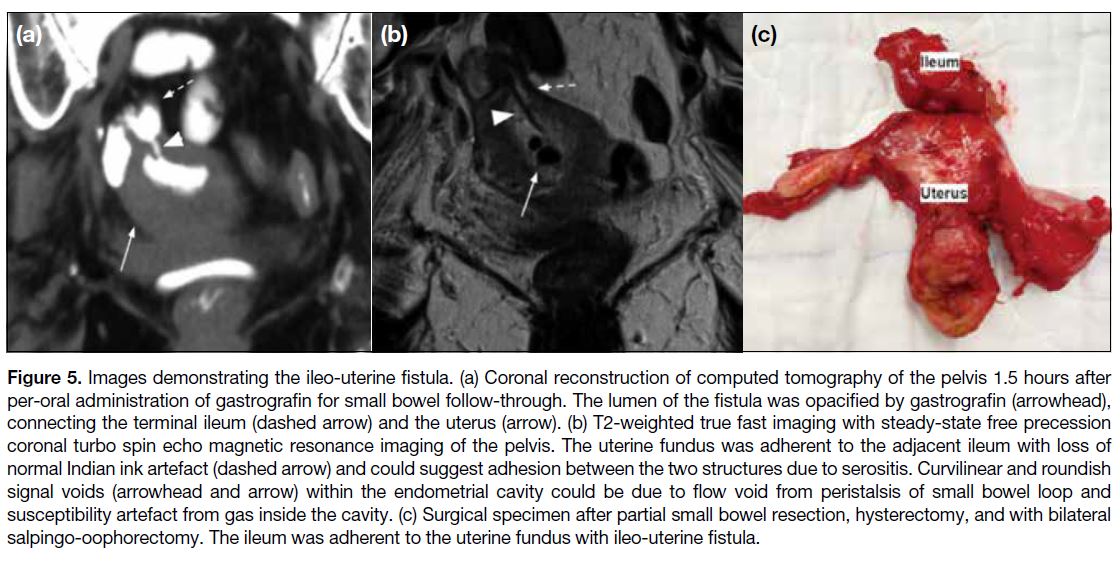

A supplementary plain CT of the pelvis identified a

contrast-opacified fistula tract between the terminal

ileum and the uterine fundus (Figure 5a).

Figure 5. Images demonstrating the ileo-uterine fistula. (a) Coronal reconstruction of computed tomography of the pelvis 1.5 hours after

per-oral administration of gastrografin for small bowel follow-through. The lumen of the fistula was opacified by gastrografin (arrowhead),

connecting the terminal ileum (dashed arrow) and the uterus (arrow). (b) T2-weighted true fast imaging with steady-state free precession

coronal turbo spin echo magnetic resonance imaging of the pelvis. The uterine fundus was adherent to the adjacent ileum with loss of

normal Indian ink artefact (dashed arrow) and could suggest adhesion between the two structures due to serositis. Curvilinear and roundish

signal voids (arrowhead and arrow) within the endometrial cavity could be due to flow void from peristalsis of small bowel loop and

susceptibility artefact from gas inside the cavity. (c) Surgical specimen after partial small bowel resection, hysterectomy, and with bilateral

salpingo-oophorectomy. The ileum was adherent to the uterine fundus with ileo-uterine fistula.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the pelvis

with axial, sagittal, and coronal pre- and post-contrast

sequences including T1-weighted turbo spin echo and

T2-weighted true fast imaging with steady-state free

precession (trueFISP) imaging were performed. The

ileo-uterine fistula tract was not seen in most of the

sequences, except in the coronal T2-weighted trueFISP

image. The uterine fundus was adherent to the adjacent

ileum with loss of normal Indian ink artefact. The open

fistula tract contained T2-weighted hyperintense fluid

and a curvilinear hypointense signal, possibly due to

flow void. Roundish signal voids in the endometrial

cavity could be due to the gas locule inside the cavity

(Figure 5b). There were no contrast-enhanced septic foci

detected.

Total abdominal hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophor-ectomy, and a partial small bowel resection of 5

cm of the distal ileum containing the fistula with end-to-end

anastomosis were performed. The surgical specimen

again clearly demonstrated the ileo-uterine fistula

connecting the ileum and the uterine fundus (Figure 5c).

Microscopic examination of the surgical specimen

showed herniation of small bowel mucosa into the

myometrium at the fistula opening and evidence of

endometritis. No endometrial hyperplasia or malignancy

was evident. The patient made an uneventful post-operative

recovery.

DISCUSSION

Ileo-uterine fistula usually presents with non-specific

symptoms such as abdominal pain and vaginal

discharge.[1] [2] [3] [4] Endometrial biopsy yielding abnormal

bowel tissue and food particles raises a suspicion of

enterouterine fistula.[5] Transvaginal ultrasonography may

reveal an intrauterine collection but rarely a fistula tract.

Diagnostic hysteroscopy can directly visualise a uterine

fistula opening.

Small enterouterine fistulas can be managed

conservatively by antibiotics and endometrial aspiration

but persistent symptoms warrant definitive surgery.[1] [3]

Further imaging investigations are important for pre-operative

planning.[1] [3] [6]

CT enables rapid assessment to exclude

pneumoperitoneum and gross pelvic abscess. It can

detect gas within the endometrial cavity, an indication

of enterouterine fistula.[7] [8] In this case, the gas within

the endometrial cavity was seen only transiently on

pre-contrast study. We hypothesise that this was due to

movement of gas to and from the fistula tract by bowel

peristalsis. This is supported by the bowel peristalsis

seen on hysteroscopy and the jet of flow void in coronal

T2-weighted trueFISP images. Gas due to recent

instrumentation would be expected to be consistently

seen in both pre- and post-contrast studies.

Fluoroscopy is the traditional imaging modality for

evaluating a pelvic fistula.[1] [2] [6] [9] Opacification of an ileo-uterine fistula tract can be achieved by small bowel follow-through

or hysterosalpingogram.[4] Hysterosalpingogram

has a higher chance of fistula opacification due to direct

manual injection of contrast into the uterine cavity but is

more invasive than small bowel follow-through. Contrast

opacification of the fistula tract in small bowel follow-through

suggests that bowel peristalsis alone builds up

sufficient pressure to open the fistula. This may predict a

likely need for surgical management due to a low chance

of spontaneous fistula closure. A complementary CT of

the pelvis right after fluoroscopy can better delineate

the three-dimensional anatomy of the contrast-opacified

fistula tract.[9]

MRI has the highest soft tissue contrast to delineate

a fistula tract. Rapid MRI sequences are essential to

minimise image degradation by bowel peristalsis.[6] [9]

We recommend T2-weighted trueFISP sequence to

look for hyperintense fluid and hypointense gas content

within the fistula. In addition, we propose that loss of normal Indian ink artefact at the fat-fluid interface in this

sequence can help detect the loss of fat plane between

the uterus and the bowel. The fistula tract was seen

only in one sequence since it opened only intermittently

under bowel peristalsis. Therefore, MRI images can be

obtained along the plane of the fistula with dynamic

study for better detection.[4]

Uterine perforation is an uncommon but known risk of

endometrial sampling with a reported incidence of 1 to 2

in 1,000 population.[10] Our patient had several risk factors

for uterine perforation including a small retroverted

uterus and chronic endometritis. The small bowel is

a freely mobile intraperitoneal structure and rarely

punctured during endometrial sampling. We hypothesise that the small bowel was relatively fixed to the uterus

due to serositis, evidenced by the loss of normal Indian

ink artefact between these structures in the coronal T2-weighted trueFISP MRI. The inflammation caused by

the presence of ileo-uterine fistula after endometrial

aspiration further led to a secondary pyometra.

In summary, ileo-uterine fistula is an extremely rare

complication following endometrial aspiration and can

cause great morbidity. A high index of clinical suspicion

should be maintained and appropriate investigations

should be carried out to guide early management.

REFERENCES

1. Hyde BJ, Byrnes JN, Occhino JA, Sheedy SP, VanBuren WM. MRI review of female pelvic fistulizing disease. J Magn Reson

Imaging. 2018;48:1172-84. Crossref

2. Fadel HE. Ileo-uterine fistula as a complication of myomectomy.

Case report. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1977;84:312-3. Crossref

3. Hawkes SZ. Enterouterine fistula; with a review of the literature and report of an unusual case. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1946;52:150-3. Crossref

4. McFarlane ME, Plummer JM, Remy T, Christie L, Laws D, Richards H, et al. Jejunouterine fistula: a case report. Gynecol Surg. 2008;5:173-5. Crossref

5. Delara R, Cornella J, Young-Fadok T, Wasson M. Colouterine fistula presenting as postmenopausal endometritis. J Minim

Invasive Gynecol. 2020;27:1234-6. Crossref

6. Moon SG, Kim SH, Lee HJ, Moon MH, Myung JS. Pelvic fistulas complicating pelvic surgery or diseases: spectrum of imaging

findings. Korean J Radiol. 2001;2:97-104. Crossref

7. Behrouzi-Lak T, Aghamohammadi V, Afshari N, Kashefi S. Salpingo enteric fistula: a case report. Int Med Case Rep J.

2020;13:221-4. Crossref

8. Dewdney SB, Mani NB, Zuckerman DA, Thaker PH. Uteroenteric fistula after uterine artery embolization. Obstet Gynecol.

2011;118:434-6. Crossref

9. Pickhardt PJ, Bhalla S, Balfe DM. Acquired gastrointestinal fistulas: classification, etiologies, and imaging evaluation. Radiology. 2002;224:9-23. Crossref

10. Cooper JM, Erickson ML. Endometrial sampling techniques in the diagnosis of abnormal uterine bleeding. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2000;27:235-44. Crossref