Antibody-Mediated Striatal Encephalitis and Aseptic Meningitis in A Child with Neuropsychiatric Lupus: A Case Report

CASE REPORT

Hong Kong J Radiol 2023 Sep;26(3):198-201 | Epub 31 Aug 2023

Antibody-Mediated Striatal Encephalitis and Aseptic Meningitis in A Child with Neuropsychiatric Lupus: A Case Report

SM Yu1, TY Yuen1, KC Chan1, KM Yam2, WP Sze2, ACH Ho2

1 Department of Imaging and Interventional Radiology, Prince of Wales Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

2 Department of Paediatrics, Prince of Wales Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

Correspondence: Dr Dr SM Yu, Department of Imaging and Interventional Radiology, Prince of Wales Hospital, Hong Kong SAR,

China. Email: fayeyupwr@gmail.com

Submitted: 10 Feb 2022; Accepted: 15 Jul 2022.

Contributors: SMY designed the study. All authors acquired and analysed the data. SMY, KMY, WPS and ACHH drafted the manuscript. SMY

and ACHH critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study,

approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Funding/Support: This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data Availability: All data generated or analysed during the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: The patient was treated in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Verbal consent for publication was obtained from the

patient’s parents.

INTRODUCTION

Neuropsychiatric systemic lupus erythematosus

(NPSLE) refers to the neurological and psychiatric

symptoms that are thought to be related to systemic

lupus erythematosus (SLE). NPSLE can be devastating,

responsible for high rates of morbidity and mortality.

It can occur any time in SLE. A recent large cohort

study showed that NPSLE affects up to 25% of patients

with juvenile-onset SLE.[1] The aetiology is thought

to be multifactorial but vasculopathy, autoantibody

production, and cytokine-induced neurotoxicity play a

major role in the pathogenesis.[2]

Our clinical report highlights two infrequent subtypes

of NPSLE–striatal encephalitis and aseptic meningitis,

with substantial clinical and radiological response to

immunosuppressants. The radiological features and

treatment response of striatal encephalitis in our case are

strikingly similar to those of the subset of anti–N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor (anti-NMDAR) autoimmune

encephalitis involving the striatum.

CASE REPORT

An 11-year-old girl with known SLE presented to our

hospital with a 1-week history of difficulty in passing

urine, followed by acute-onset urinary retention. She was

also suspected to have depersonalisation-derealisation

syndrome for the last 1 year. She experienced progressive

worsening with avolition, apathetic, mental slowness,

and insomnia 4 weeks prior to this acute presentation.

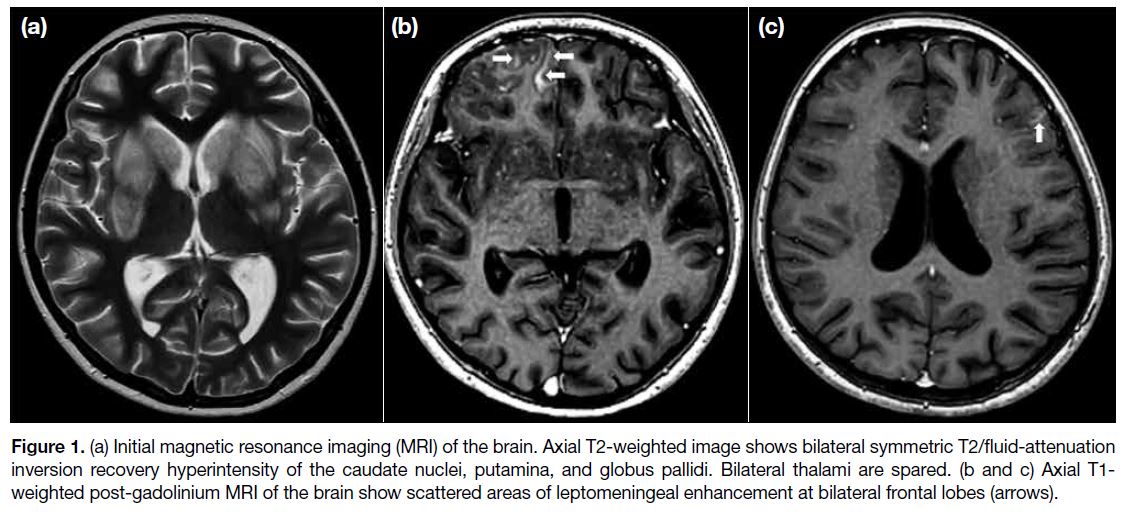

Urgent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) brain

examination demonstrated bilateral symmetrical T2/fluid-attenuated

inversion recovery (FLAIR) hyperintensity of

the caudate nuclei, putamina, and globus pallidus without

contrast enhancement or restricted diffusion. Bilateral

thalami were spared (Figure 1a). Following intravenous

gadolinium injection, scattered areas of leptomeningeal

enhancement were present at bilateral frontal lobes and

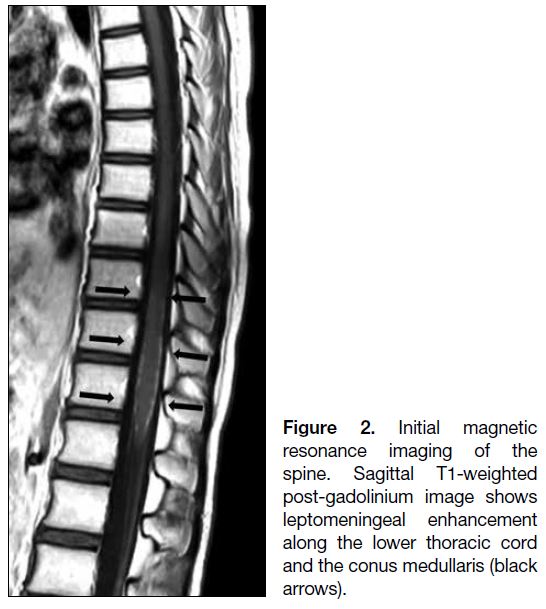

the right cerebellar hemisphere (Figure 1b and 1c). MRI

of the spine demonstrated leptomeningeal enhancement

along the lower thoracic cord and the conus medullaris

(Figure 2).

Figure 1. (a) Initial magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain. Axial T2-weighted image shows bilateral symmetric T2/fluid-attenuation

inversion recovery hyperintensity of the caudate nuclei, putamina, and globus pallidi. Bilateral thalami are spared. (b and c) Axial T1-weighted post-gadolinium MRI of the brain show scattered areas of leptomeningeal enhancement at bilateral frontal lobes (arrows).

Figure 2. Initial magnetic

resonance imaging of the spine. Sagittal T1-weighted post-gadolinium image shows leptomeningeal enhancement along the lower thoracic cord and the conus medullaris (black arrows).

The patient underwent extensive workup and was

positive for antinuclear antibodies, anti–double-stranded

DNA, anti-ribonucleoprotein, anti-extractable nuclear

antigen antibodies including anti-Ro, anti-La and

anti-Sm, as well as anti-ribosomal P antibodies; anti-NMDAR antibody was negative. Cerebrospinal fluid analysis revealed mildly elevated protein and normal leucocyte count. Cerebrospinal fluid gram stain, culture

and virology were negative.

The patient was empirically treated with intravenous

acyclovir, oral oseltamivir, and intravenous ciprofloxacin

at the time of presentation for 2 days without any clinical

improvement. Based on the clinical and characteristic

MRI features, a working diagnosis was made of

NPSLE with antibody-mediated striatal encephalitis

and aseptic meningitis. Antiviral and antibiotic

treatments were discontinued and immunosuppressive

treatment commenced. The patient received 5 days of

pulse intravenous methylprednisolone and intravenous

cyclophosphamide, followed by oral prednisolone and

mycophenolate mofetil.

Follow-up MRI of the brain was performed 3 days later

to guide clinical management. There was complete

resolution of the leptomeningeal enhancement but

persistent striatal T2/FLAIR hyperintensity. With

treatment, the clinical status of the patient gradually

improved. Foley was weaned off successfully. Her

mental state and sleep quality improved.

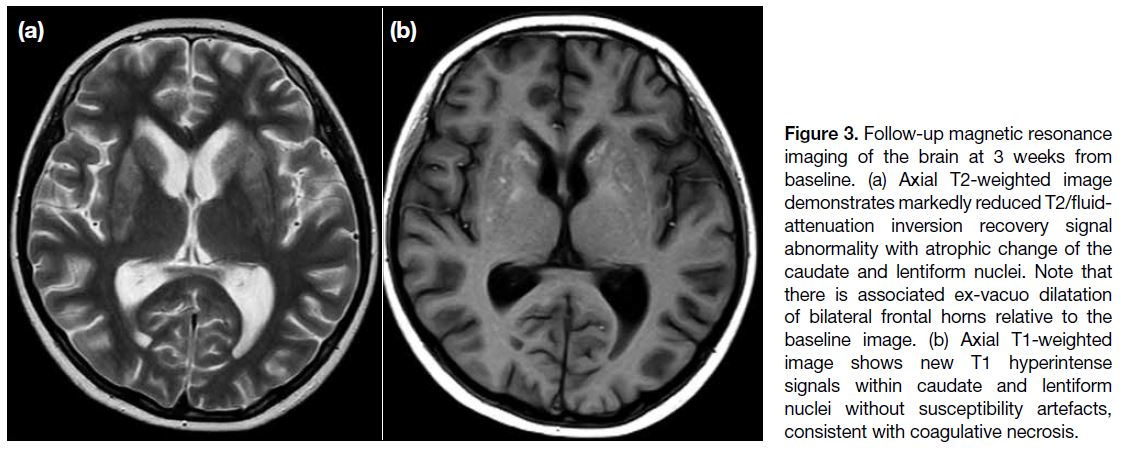

Another follow-up MRI of the brain 3 weeks from

baseline demonstrated reduction in the extent of

T2/FLAIR signal abnormality but interval development

of caudate and lentiform nuclei atrophy (Figure 3a).

There was also novel T1 hyperintensity within the

caudate and lentiform nuclei without associated susceptibility artefacts, consistent with coagulative necrosis (Figure 3b).

Figure 3. Follow-up magnetic resonance imaging of the brain at 3 weeks from baseline. (a) Axial T2-weighted image demonstrates markedly reduced T2/fluid-attenuation inversion recovery signal abnormality with atrophic change of the caudate and lentiform nuclei. Note that there is associated ex-vacuo dilatation of bilateral frontal horns relative to the baseline image. (b) Axial T1-weighted image shows new T1 hyperintense signals within caudate and lentiform nuclei without susceptibility artefacts, consistent with coagulative necrosis.

DISCUSSION

NPSLE describes a wide spectrum of peripheral and

central nervous system manifestations. The widely

quoted classification of NPSLE, made by an American

College of Rheumatology expert committee in 1999,

comprised 12 central and seven peripheral nervous system

manifestations.[3] Case definitions including diagnostic

criteria, exclusions, and methods of ascertainment were

developed for each specific neuropsychiatric syndrome.[3]

Among these, headache, mood disorders, cognitive

dysfunction, seizures, movement disorders, and

cerebrovascular disease are the most common NPSLE

manifestations.[1] [4] [5]

Neuroimaging plays a vital role in the diagnosis of

NPSLE and MRI is the preferred imaging modality for

assessment of neurological manifestations although a

negative scan does not exclude the presence of active

NPSLE. A wide range of radiological abnormalities has

been described but are often non-specific. In a single-centre

retrospective study by Al-Obaidi et al,[5] the major

MRI findings in juvenile-onset NPSLE were focal T2-weighted white matter hyperintensities (33%), brain

atrophy (18.5%), cortical grey matter lesions (3%),

and basilar artery territory infarction (3%), although a

majority of patients (59%) showed no MRI abnormalities

despite clinically active NPSLE. Striatal encephalitis

and aseptic meningitis have rarely been described as

characteristic manifestations of neuropsychiatric lupus,[6] [7] [8]

although they were coexistent in our patient.

Antibody-mediated striatal encephalitis is a rare

but characteristic manifestation of NPSLE.[6] [7] The

radiological features and clinical course of lupus-related

antibody-mediated striatal encephalitis closely

resemble those of anti-NMDAR striatal encephalitis. It

is suggested that peripheral anti–double-stranded DNA

antibodies, a specific serum autoantibody in SLE, may

enter the central nervous system to cross-react with

NMDAR antigens[6] [7] and mediate a non-thrombotic

and non-vasculitic pathology with features of neuronal

excitotoxicity.[6] Other autoantibodies thought to cause

NPSLE include anti-neuronal, anti-NMDAR2, anti-ribosomal

P, and anti-endothelial antibodies.[9]

The radiological pattern of bilateral symmetrical T2

hyperintensity involving lentiform and caudate nuclei

typically suggests systemic or metabolic causes. The

characteristic sparing of bilateral thalami and lack of

restricted diffusion and contrast enhancement provide

important clues for excluding multiple conditions

in the differential list including hypoglycaemia,

hypoxic ischaemic encephalopathy, extrapontine

myelinolysis, arterial occlusion, venous thrombosis, and

Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease. Other differentials including

organophosphate or methanol poisoning can be excluded

by clinical presentation and toxicology.

In an appropriate clinical setting, such as in our patient,

the presence of bilateral symmetrical T2 hyperintense

signal changes within the caudate and putamen without

evidence of restricted diffusion or contrast enhancement

was strongly suggestive of autoimmune encephalitis

of the striatum.[7] Intrinsic T1 hyperintensity within the striatum, also evident in our patient, may indicate a poor prognosis. This has been proposed to be related

to the development of coagulative necrosis secondary

to prolonged antibody-mediated inflammation and

excitatory glutamate neurotoxicity.[7]

Aseptic meningitis is another manifestation of NPSLE.

It is possibly mediated by a combination of mechanisms

such as anti-neuronal antibodies, antiphospholipid

antibodies, immune complex–mediated vasculitis, and

cytokines. Due to the non-specific radiological findings,

more common causes of leptomeningeal enhancement,

including infection and malignancy, must be excluded

before establishing the diagnosis.[4] Compared with

pyogenic meningitis, cerebrospinal fluid leucocytes

and proteins are usually lower in cases of lupus-related

aseptic meningitis.

In children with SLE, neuropsychiatric manifestation

is frequently associated with high overall SLE activity.

Aggressive treatment, including systemic corticosteroid

and immunosuppressants, is often required to control

the autoimmune process and avoid further damage.[4]

Close collaboration between the radiologist, paediatric

rheumatologist and neurologist is crucial to reach a

prompt diagnosis and maximise clinical outcomes in

these patients with NPSLE.

CONCLUSION

We present a patient with NPSLE presenting as

striatal encephalitis and aseptic meningitis who

demonstrated a good clinical and radiological response

to immunosuppressive therapy. The clinical course

and imaging features of antibody-mediated striated encephalitis in our patient closely resemble those of a

striatal variant of anti-NMDAR encephalitis.

Neuroimaging plays an important role in diagnosis,

monitoring treatment response and prognostication

by identifying complications such as brain atrophy or

intrinsic basal ganglionic T1 hyperintensity. Prompt

diagnosis and early treatment facilitates optimisation of

clinical outcomes.

REFERENCES

1. Giani T, Smith EM, Al-Abadi E, Armon K, Bailey K, Ciurtin C,

et al. Neuropsychiatric involvement in juvenile-onset systemic

lupus erythematosus: data from the UK juvenile-onset systemic

lupus erythematosus cohort study. Lupus. 2021;30:1955-65. Crossref

2. Hanly JG. Neuropsychiatric lupus. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2001;3:205-12. Crossref

3. The American College of Rheumatology nomenclature and case definitions for neuropsychiatric lupus syndromes [editorial]. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42:599-608. Crossref

4. Kivity S, Agmon-Levin N, Zandman-Goddard G, Chapman J, Shoenfeld Y. Neuropsychiatric lupus: a mosaic of clinical

presentations. BMC Med. 2015;13:43. Crossref

5. Al-Obaidi M, Saunders D, Brown S, Ramsden L, Martin N, Moraitis E, et al. Evaluation of magnetic resonance imaging

abnormalities in juvenile onset neuropsychiatric systemic lupus

erythematosus. Clin Rheumatol. 2016;35:2449-56. Crossref

6. DeGiorgio LA, Konstantinov KN, Lee SC, Hardin JA, Volpe BT,

Diamond B. A subset of lupus anti-DNA antibodies cross-reacts

with the NR2 glutamate receptor in systemic lupus erythematosus.

Nat Med. 2001;7:1189-93. Crossref

7. Kelley BP, Corrigan JJ, Patel SC, Griffith BD. Neuropsychiatric lupus with antibody-mediated striatal encephalitis. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2018;39:2263-69. Crossref

8. Canoso JJ, Cohen AS. Aseptic meningitis in systemic lupus erythematosus. Report of three cases. Arthritis Rheum. 1975;18:369-74. Crossref

9. Govoni M, Hanly JG. The management of neuropsychiatric lupus in the 21st century: still so many unmet needs? Rheumatology (Oxford). 2020;59(Suppl5):v52-62. Crossref