Effect of Elective Inguinal Irradiation in Low Rectal Cancer with Anal Canal Invasion

ORIGINAL ARTICLE CME

Hong Kong J Radiol 2023 Sep;26(3):174-84 | Epub 7 Sep 2023

Effect of Elective Inguinal Irradiation in Low Rectal Cancer with Anal Canal Invasion

HS Wong, WYL Choi, KT Yuen

Department of Oncology, Princess Margaret Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

Correspondence: Dr HS Wong, Department of Oncology, Princess Margaret Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China. Email: whs871@ha.org.hk

Submitted: 26 Oct 2022; Accepted: 12 Dec 2022.

Contributors: HSW designed the study, acquired and analysed the data, and drafted the manuscript. WYLC and KTY critically revised the

manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for

publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Funding/Support: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data Availability: All data generated or analysed during the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: This research was approved by the Kowloon West Cluster Research Ethics Committee of Hospital Authority, Hong Kong [Ref

No.: KW/EX-22-035 (171-04)]. A waiver of patient consent was obtained from the Committee due to the retrospective nature of the study.

Declaration: This manuscript was posted on Research Square as a registered online preprint (https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-1914914/v1).

Abstract

Introduction

We investigated whether omitting elective inguinal irradiation during neoadjuvant or adjuvant

radiation/chemoradiation therapy is feasible for patients with low rectal cancer with anal canal invasion (ACI) and

nonpalpable inguinal lymph nodes (ILNs) at presentation.

Methods

Ninety low rectal cancer patients with ACI who underwent neoadjuvant or adjuvant radiation/chemoradiation therapy with or without elective inguinal radiotherapy (RT) between 2011 and 2021 were recruited.

None had palpable ILN. The failure pattern, ILN recurrence rate, survival data, and prognostic factors were analysed.

Results

Among 81 patients omitting elective inguinal RT, the 3-year ILN failure rate was 4.9%. Meanwhile, there

was no inguinal failure with elective RT. One case of isolated ILN failure was successfully salvaged by surgery. In

multivariate Cox regression analysis, positive pathological lymph node(s) after neoadjuvant treatment predicted a

worse locoregional recurrence-free survival (odds ratio [OR] = 9.066; p ≤ 0.001), distant metastasis recurrence-free

survival (OR = 6.426; p = 0.002), and overall survival (OR = 11.750; p ≤ 0.001). Chemotherapy concurrent with RT

was associated with better locoregional recurrence-free survival (OR = 33.338; p = 0.001) and overall survival (OR

= 13.917; p = 0.006). Grade ≥3 acute and chronic toxicities occurred in 33.3% and 19.8%, respectively, of patients

with elective inguinal irradiation, compared with 11.1% and 7.4%, respectively, in patients who did not receive it.

Conclusion

Omission of elective inguinal irradiation resulted in a low inguinal failure rate and similar survival

outcomes for low rectal cancer patients with ACI. Additionally, it might spare patients from unnecessary acute and chronic RT toxicities.

Key Words: Chemoradiotherapy; Chemoradiotherapy, adjuvant; Neoadjuvant therapy; Rectal neoplasms

中文摘要

伴肛門侵犯的低位直腸癌患者進行預防性腹股溝照射的影響

王曉生、蔡源霖、袁錦堂

引言

我們探討為臨床上出現肛門侵犯及觸摸不到腹股溝淋巴結的低位直腸癌患者進行前輔助放療或輔助放療/放化療時不接受預防性腹股溝照射是否可行。

方法

本研究招募了90名出現肛門侵犯的低位直腸癌患者,他們在2011至2021年間曾進行前輔助放療或輔助放療/放化療,部分有接受預防性腹股溝放療,部分則沒有。全部患者均沒有觸摸到的腹股溝淋巴結。本研究分析了失敗模式、腹股溝淋巴結復發率、存活數據及預後因素。

結果

在81名沒有接受預防性腹股溝放療的患者中,三年腹股溝淋巴結失敗率為4.9%。同時,預防性放療並沒有腹股溝失敗的情況。一例個別的腹股溝淋巴結失敗成功通過手術挽救。多變量Cox迴歸分析顯示,前輔助放療後的陽性病理性淋巴結預測較差的局部無復發存活(勝算比 = 9.066;p ≤ 0.001)、無遠端轉移復發存活(勝算比 = 6.426;p = 0.002)及整體存活(勝算比 = 11.750;p ≤ 0.001)。放療期間同時進行化療與較佳的局部無復發存活(勝算比 = 33.338;p = 0.001)及整體存活(勝算比 = 13.917;p = 0.006)相關。在接受預防性腹股溝照射的患者中,分別有33.3%及19.8%出現≥3級急性及慢性毒性;沒有接受該照射的患者出現上述兩種毒性的比例則分別為11.1%及7.4%。

結論

沒有接受預防性腹股溝照射的伴肛門侵犯的低位直腸癌患者,其腹股溝失敗率低,與有接受該照射的患者相比,存活結果相近,而且可能避免出現不必要的急性及慢性放療毒性。

INTRODUCTION

Neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy (CRT) reduces the risk

of a positive circumferential margin and local recurrence

in patients with low rectal cancer.[1] Prospective

randomised trials have demonstrated significantly lower

locoregional recurrence rates with adjuvant CRT when

compared with observation or either modality alone in

stage II/III rectal cancer.[2]

The clinical target volume (CTV) during radiation/chemoradiation therapy must cover areas with potential

metastatic risk while avoiding organs at risk to avoid

radiation-related complications. In low rectal cancer

with anal canal invasion (ACI), tumour can spread to

inguinal lymph nodes (ILNs) through the perirectal

and pudendal lymphatics, as well as the lymphatics

draining the infradentate and perianal skin. An advanced

rectal primary tumour can cause proximal lymphatic

obstruction and retrograde lymph node metastasis.[3]

The European Society for Medical Oncology Clinical

Practice Guidelines proposed in 2010 recommends prophylactic irradiation of medial ILNs if the rectal

tumour extends below the dentate line.[4] Radiation

of ILNs in cases where tumour extends into the anal

sphincter has been advocated by the 2016 international

consensus guidelines on CTV delineation.[5] According

to the 2020 American Society for Radiation Oncology

Clinical Practice Guidelines, ILNs and external iliac

nodes should be conditionally included in the CTV for

patients with rectal malignancies with ACI.[6] However,

the contouring atlas of the Radiation Therapy Oncology

Group has no consensus on the subject.[7]

In three retrospective trials,[8] [9] [10] the ILN failure rates in

rectal cancer patients with ACI who received neoadjuvant

or adjuvant radiation/chemoradiation therapy without

elective inguinal irradiation were not high enough (3-year

failure rate: 3.7%[8]; 5-year actuarial rate: 3.5%-4%[9] [10]) to

justify inguinal irradiation as a standard procedure.

The treatment policy at our institution for low rectal

cancer with ACI and clinically negative ILN at presentation has been based on the practice of the

attending oncologists. We looked at the feasibility of

omitting elective inguinal irradiation for patients with

low rectal cancer with ACI and clinically negative ILN.

METHODS

Data Collection

From 2011 to 2021, the clinical data of 110 patients with

low rectal cancer with ACI who received neoadjuvant

or adjuvant radiation/chemoradiation therapy in our

tertiary oncology centre were collected from the

institutional database and retrospectively reviewed. The

inclusion criteria were: (1) histologically confirmed

locally advanced rectal adenocarcinoma without distant

metastasis (based on the Eighth Edition of the American

Joint Committee on Cancer Staging Manual); (2)

tumours with ACI, defined as the tumour’s lower edge

being within 3 cm of the anal verge (or being located at

or below the dentate line) on digital rectal examination,

colonoscopy or magnetic resonance imaging; and (3)

an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance

status score of 0 to 2.

The exclusion criteria were: (1) inguinal metastasis

on presentation by clinical and imaging studies;

(2) occurrence of distant failure before surgery; (3)

ineligibility for radical surgery as determined by clinical

and imaging studies; (4) local excision; (5) incomplete

radiation/chemoradiation therapy; (6) in the setting

of recurrence indicated for radiation/chemoradiation

therapy; and (7) second malignancies within 5 years.

Missing data were dealt with by listwise deletion.

Patients lost to follow-up were censored and their life

expectancy was counted till the last follow-up date.

Pretreatment Workup

Pretreatment workup for clinical staging included digital

rectal examination, complete blood count, liver and

renal function tests, serum carcinoembryonic antigen,

colonoscopy, chest radiography, computed tomography

(CT) of the thorax, abdomen and pelvis with or without

transrectal ultrasonography, and pelvic magnetic

resonance imaging. Fluorine-18 fluorodeoxyglucose

positron emission tomography/CT (PET/CT) was

performed at the physician’s discretion and patient

accessibility.

Chemoradiotherapy Treatment

The patients received either long-course or short-course

radiotherapy (RT). Long-course RT was administered to the entire pelvis at a dose of 45 Gy in 25 daily fractions,

followed by a 5.4-Gy boost in three daily fractions over

5.5 weeks. Short-course RT was delivered to the whole

pelvis at a dose of 25 Gy in 5 daily fractions over 1

week. All patients underwent CT simulation for three-dimensional

conformal planning, with a comfortably

full bladder and an empty rectum. In patients declining

elective inguinal irradiation, a three-field treatment

plan was adopted using a posterior-anterior field and

lateral opposing beams. With patients electing inguinal

irradiation, a pair of anterior-posterior opposing fields

was used. The prescription dose was set at the 100%

isodose line. The initial radiation field encompassed the

gross tumour volume (GTV) (preoperative radiation/chemoradiation therapy) or tumour bed (postoperative

CRT), and the regional lymphatics including the

mesorectal, internal iliac, presacral, and distal common

iliac lymphatics plus or minus ILN. The superior

boundary was the L5-S1 junction; the inferior border

was set 3 cm caudal to the GTV or tumour bed and the

anterior border was placed 3 cm anterior to the sacral

promontory, while the posterior border was placed 1 cm

posterior to the sacrum. The GTV or tumour bed were

included in the boost field, with 3-cm margins in all

directions.

Chemotherapy was administered concurrently with

long-course RT using bolus 5-fluorouracil (FU)

[500 mg/m2 intravenous bolus; Days 1-3 and Days

29-31].[11] As there has been evidence for better treatment

outcomes with continuous oral capecitabine,[12] [13]

continuous oral capecitabine (825 mg/m2 twice per

day) was used as a concomitant chemotherapeutic agent

since April 2021. If patients were deemed unsuitable for

chemotherapy, long-course RT alone was an alternative.

Either abdominal-perineal resection or low anterior

resection with complete mesorectal excision was

performed. Typically, the interval between preoperative

CRT and surgery was 8 weeks, and that between surgery

and postoperative CRT was 10 weeks. Four months

of adjuvant chemotherapy was administered using six

cycles of capecitabine and oxaliplatin, eight cycles of

modified leucovorin/fluorouracil/oxaliplatin, or six

cycles of capecitabine depending on patients’ tolerance.

Study Endpoints

The 3-year inguinal failure rate, locoregional recurrence-free survival (LRFS), distant metastasis recurrence-free

survival (DMRFS), overall survival (OS), and failure

pattern were analysed. LRFS, DMRFS, and OS risk

factors were also investigated. LRFS was measured from the start of treatment to locoregional relapse, death from

any causes, or last follow-up. DMRFS was measured

from the start of treatment to distant relapse, death from

any causes, or last follow-up. OS was calculated from

the date of the first treatment to the date of death or the

last follow-up.

Follow-up

The patients were evaluated for symptoms, physical

examination findings, and blood tests including

carcinoembryonic antigen in outpatient clinics on a

regular basis. A thorax, abdomen, and pelvic CT or

PET/CT would be arranged if there was clinical suspicion

of disease recurrence. Colonoscopies were performed 1

year after surgery and every 3 years thereafter.

Statistical Analysis

The 3-year LRFS, DMRFS, and OS rates were presented

using the Kaplan-Meier method. Fisher’s exact tests

were used to explore the difference between categorical

variables, while Mann–Whitney U tests were used to

explore the difference between continuous variables.

Clinicopathologic variables were entered into a Cox

proportional hazard regression multivariable regression

model and analysed for effects on LRFS, DMRFS and

OS. All analyses were performed using SPSS (Windows

version 21.0; IBM Corp, Armonk [NY], United States). A

p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Research Reporting Guidelines

The STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of

Observational Studies in Epidemiology) checklist for

observational cohort studies was implemented in the

preparation of the manuscript.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

This study enrolled 90 eligible individuals from a

larger primary cohort of 110 patients. The full course of

radiation/chemoradiation therapy was completed by all

patients. The study excluded five patients who refused

or were ineligible for surgery, six patients who had local

excision only, one patient with upfront distant metastasis,

four patients who developed distant metastasis after

neoadjuvant radiation/chemoradiation, two patients

with upfront inguinal metastasis, and two patients with

recurrent rectal cancer.

The median duration of follow-up was 45 months (range,

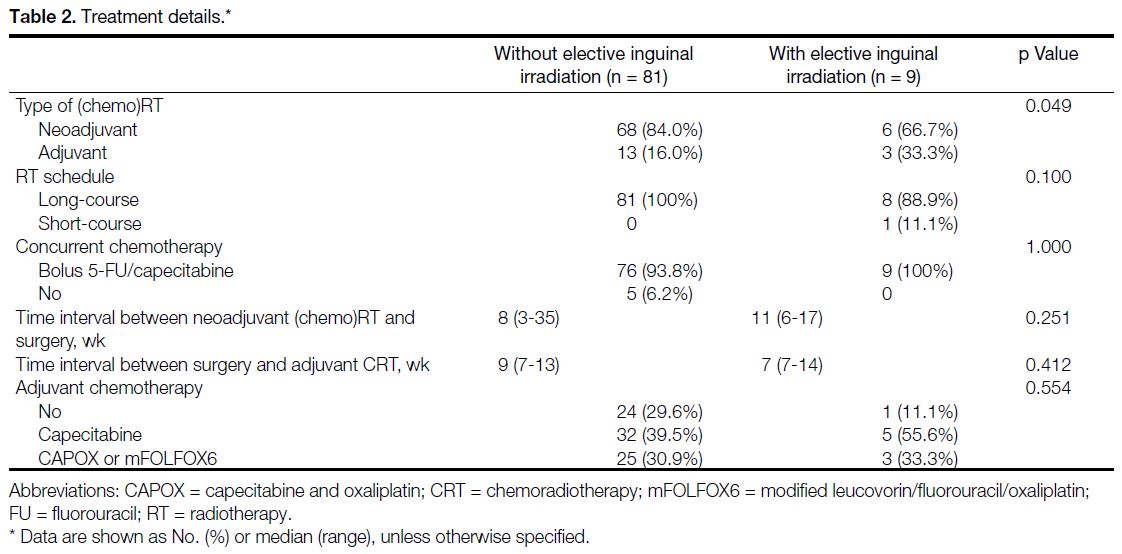

2-118). Tables 1 and 2 list the clinical data, pathological data, and treatment characteristics of the patients.

Table 1. Baseline clinical and pathological characteristics of patients with and without elective inguinal irradiation.

Table 2. Treatment details.

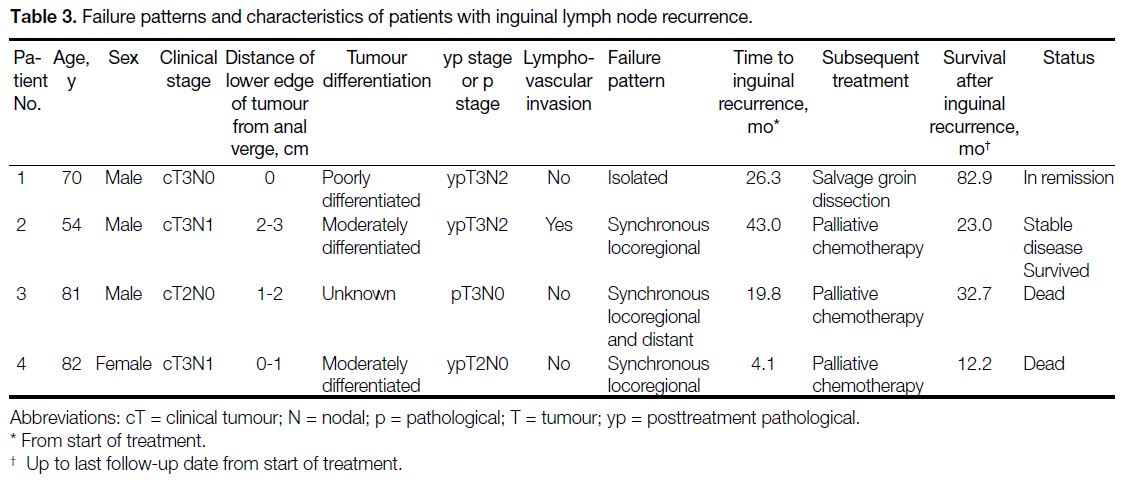

Failure Rates and Patterns

Patients who did not receive elective inguinal radiation

(n = 81) had a 3-year ILN failure rate of 4.9% (n = 4).

Patients who received elective inguinal radiation (n = 9) did not experience any inguinal failure. Of the four

patients with ILN failure, only one of them had isolated

ILN failure, while the other three had synchronous

locoregional recurrence and/or distant failure. In other

words, omitting inguinal irradiation resulted in only

one case (1.2%) of isolated inguinal nodal failure.

Salvage surgery was successfully performed for this

patient, who achieved disease remission and survived.

Palliative chemotherapy was administered to patients

with synchronous locoregional recurrence and/or distant

failure, two of whom died due to disease progression.

Failure patterns and characteristics of patients with ILN

recurrence are listed in Table 3.

Table 3. Failure patterns and characteristics of patients with inguinal lymph node recurrence.

Survival Outcomes and Prognostic Factors

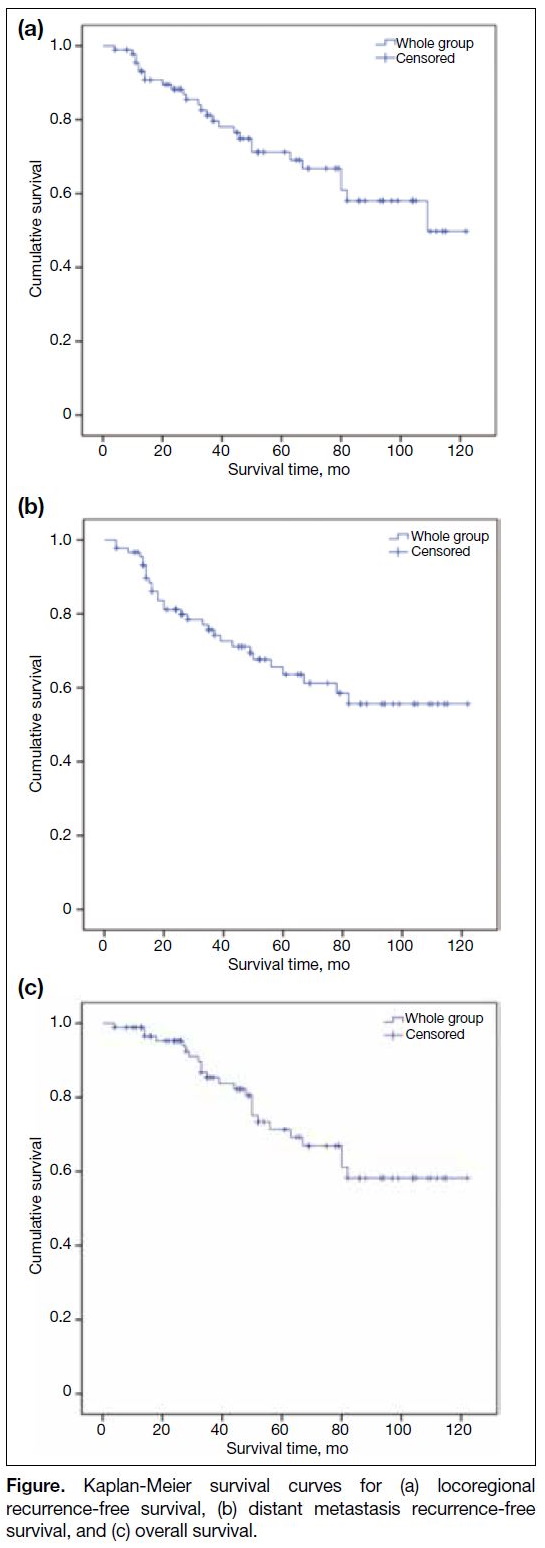

The Figure illustrates the Kaplan-Meier curves, depicting 3-year LRFS, DMRFS, and OS of 81.1%, 77.0%, and 86.8%, respectively.

Figure. Kaplan-Meier survival curves for (a) locoregional recurrence-free survival, (b) distant metastasis recurrence-free survival, and (c) overall survival.

In multivariable Cox regression analysis, positive

pathological lymph node after neoadjuvant treatment

predicted worse LRFS (odds ratio [OR] = 9.066, 95%

confidence interval [CI] = 3.291-24.972; p < 0.001),

DMRFS (OR = 6.426, 95% CI = 1.944-21.244; p = 0.002) and OS (OR = 11.750, 95% CI = 3.583-38.526; p < 0.001). Positive tumour resection margin correlated

with worse LRFS (OR = 27.296, 95% CI = 5.592-133.241; p < 0.001) and OS (OR = 49.982, 95% CI = 4.561-547.759; p = 0.001). Chemotherapy concurrent

with RT was associated with better LRFS (OR = 33.338,

95% CI = 4.525-245.633; p = 0.001) and OS (OR = 13.917, 95% CI = 2.095-92.437; p = 0.006). Meanwhile,

elective inguinal RT was not associated with statistical

differences in LRFS, DMRFS or OS. Details of simple

and multivariable analyses are shown in Table 4.

Table 4. Simple and multivariable Cox regression models for locoregional recurrence-free survival (LRFS), distant metastasis recurrence-free survival (DMRFS), and overall survival (OS).

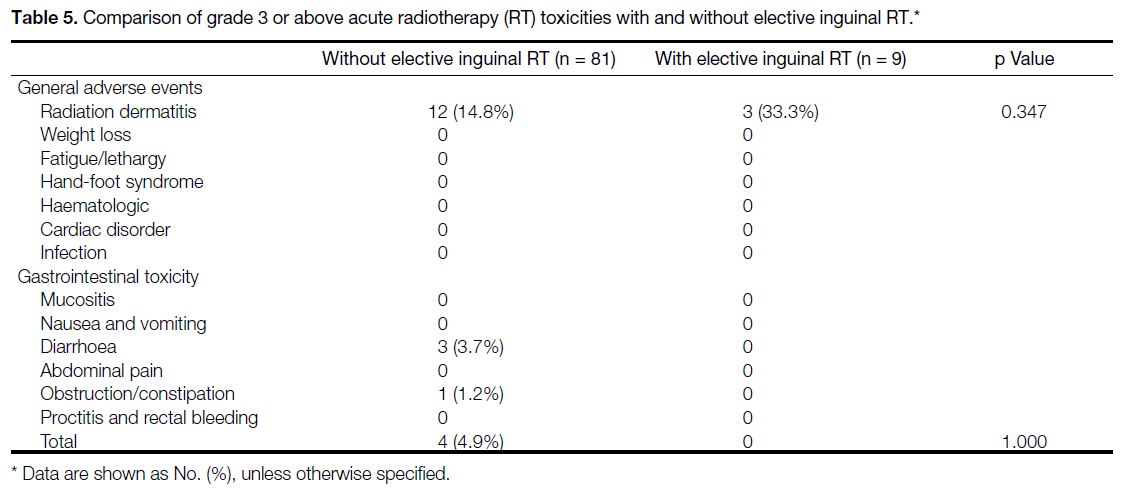

Treatment Toxicities

Grade ≥3 acute toxicity occurred in 16 out of 81 of

patients (19.8%) who did not receive inguinal radiation

and 3 out of 9 patients (33.3%) who underwent inguinal

RT. Inguinal irradiation caused 3 out of 9 patients (33.3%)

to develop grade ≥3 perineal dermatitis, compared to 12

out of 81 patients (14.8%) who did not have inguinal

irradiation. The above difference, however, did not reach

statistical significance. Table 5 shows the acute toxicities

profile (Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse

Events Grade ≥3).

Table 5. Comparison of grade 3 or above acute radiotherapy (RT) toxicities with and without elective inguinal RT.

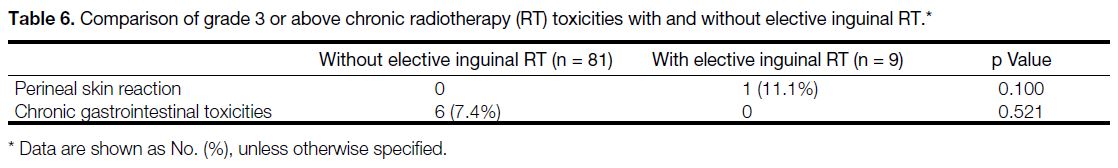

In terms of chronic toxicity, 1 out of 9 patients (11.1%)

who had elective inguinal irradiation developed a

protracted gap wound after excision of a perineal

recurrence, while there were no recorded chronic perineal

skin toxicities in patients who did not receive inguinal

irradiation. Among the 81 patients who did not receive

elective inguinal irradiation, five (6.2%) experienced

intestinal obstruction and one (1.2%) developed

rectovaginal fistula. No chronic gastrointestinal toxicities

have been reported in patients with elective inguinal

irradiation, though the abovementioned differences were not statistically significant. Table 6 shows the chronic

toxicities profile (the Radiation Therapy Oncology

Group and the European Organisation for Research and

Treatment of Cancer Grade ≥3).

Table 6. Comparison of grade 3 or above chronic radiotherapy (RT) toxicities with and without elective inguinal RT.

DISCUSSION

For rectal cancer, determining optimal radiation

targets based on their location and mode of spread is

a challenge. Despite the theoretical risk that tumour

cells in low rectal cancer with ACI could spread to the

ILN region, there has been no consensus on whether to include the inguinal nodal region in CTV for this patient subgroup. More clinical evidence is needed to optimise the CTV for these patients in order to reduce irradiation

of normal tissue.

The low ILN failure rate (4.9%) in our study, which

mirrored the findings of other retrospective studies,[8] [9] [10]

showed that most patients with low rectal cancer

with ACI would not benefit from elective inguinal

irradiation during neoadjuvant or adjuvant (chemo)RT. Some experts, however, still recommend elective

ILN irradiation based on acceptable morbidities.[14] In

our study, the acute toxicity associated with inguinal

irradiation cannot be neglected. There were more

acute grade 3 perineal dermatitis among patients who

received elective inguinal irradiation (33.3% vs. 14.8%),

though none required a treatment break. Meanwhile,

the reported chronic complications of elective inguinal

irradiation appeared relatively minor in our study. Only

1 out of 9 patients (11.1%) who had elective inguinal

irradiation developed a protracted gap wound after

perineal recurrence.

Measures were developed to identify patients who were

at a higher risk of developing inguinal nodal metastasis.

Firstly, Song et al[8] created a nomogram to predict the

probability of ILN failures according to tumour location,

histological grade, and presence of perineural invasion.

It can be used as a guide to select patients for elective

inguinal irradiation at high risk of ILN failure, but the

presence of perineural invasion may not be known until

postoperatively. Shiratori et al[15] have also noted that

dentate line involvement and ILNs > 8 mm may predict

the development of inguinal nodal metastasis. PET/CT

has been suggested to detect abnormal inguinal uptake

for inguinal nodal region irradiation. Although up to

17% of patients with distal rectal cancer, especially

those ultra-low tumours, had inguinal nodes showing

fluorodeoxyglucose uptake on PET/CT, the false

positivity rate was high, as nearly half of these nodes no

longer demonstrated uptake after CRT despite the fact

that the inguinal region is not included in the radiation

field. Moreover, none of these patients in that study

developed inguinal recurrence after 22 months of follow-up.[16] A review of sentinel nodes in anal cancer revealed

that 44% of all node metastases located in lymph nodes

measured <5 mm in diameter.[17] The spatial resolution of

PET/CT is limited to a few millimetres, suggesting it may

not have sufficient sensitivity and specificity to select

outpatients for inguinal irradiation.[18] The sentinel node

technique was also studied in rectal cancer with ACI.

A small prospective study of 15 patients showed no

recurrence in the groin for patients whose sentinel

lymph nodes were determined to be negative for

metastatic adenocarcinoma.[19] However, a systematic

review indicated that the sentinel lymph node procedure

showed only a fair sensitivity rate of 82% (95% CI = 60%-93%), regardless of tumour stage, localisation

or pathological technique.[20] Due to the relatively low

sensitivity, technically demanding procedures, risk of

surgical morbidity, and doubtful impact on subsequent

clinical management, this is not currently a standard practice for

low rectal cancer with ACI.

Only one patient (25%) developed isolated ILN

metastases among all the four patients with inguinal

recurrence. Salvage treatment for isolated ILN recurrence

can provide long-term ILN control in our study. As a

result, prophylactic treatment of the inguinal region

may not be necessary. The other three patients (75%)

who experienced inguinal recurrence had synchronous

locoregional and/or distant recurrences. One may

question whether early detection and treatment of occult

inguinal nodal metastases can help prevent subsequent

distant metastases. Damin et al[18] observed that despite

inguinal dissection, 75% of sentinel ILN–positive cases

developed hepatic or pulmonary metastases within 6

months of the surgery. Thus, localised treatment of the

inguinal region may not affect the final clinical outcome,

which is determined mainly by the occurrence of

metastasis to distant organs.[19] In this context, a sentinel

lymph node metastasis could represent a potential marker

for systemic dissemination of the disease.[19]

From our results, patients who had positive pathological

lymph node(s) following neoadjuvant therapy and/or a

positive resection margin had an inferior rate of 3-year

LRFS and OS, implying that more aggressive neoadjuvant

treatment is needed to shrink the tumour before surgery,

such as the addition of an induction or consolidation

chemotherapy regimen. Several recently published large-scale

randomised controlled trials consistently showed

that total neoadjuvant treatment can improve disease-free

survival, pathological complete remission rate, and

the risk of disease-related treatment failure in patients

with high-risk rectal cancer.[20] [21] [22] [23] Among them, the phase 3 STELLAR trial was the first trial to demonstrate OS

benefit, which found that short-course RT followed by

perioperative chemotherapy resulted in better 3-year OS

rates than CRT followed by postoperative chemotherapy,

with 86.5% vs. 75.1% (OR = 0.67, 95% CI = 0.46-0.97; p = 0.033).[23] Furthermore, in our study, as compared to

radiation alone, concomitant chemotherapy was linked

with a superior LRFS and OS. A Cochrane review found

that preoperative CRT improved local control (OR = 0.56, 95% CI = 0.42-0.75; p < 0.0001) in resectable stage

III rectal cancer but did not increase OS (OR = 1.01, 95%

CI = 0.85-1.20; p = 0.88).[24] The STELLAR OS benefit

may be attributable to different patient selection criteria

as our included patient population was restricted to low

rectal cancer with ACI. This high-risk group may derive

more benefit from concurrent chemotherapy. Additional

studies are encouraged to validate the OS benefit of

preoperative CRT against RT alone in resectable low

rectal cancer with ACI.

Song et al[8] also investigated the impact of excluding

irradiation of ILNs during neoadjuvant (chemo)RT in

low rectal cancer with ACI. Their 3-year ILN failure

rate was 3.7%. Our 3-year RFS rate (76.6% vs. 77.7%)

is comparable to their disease-free survival rate, but our

3-year OS rate (86.8% vs. 91.9%) outcome appeared

slightly inferior. Reasons for our relatively inferior OS

may be multifactorial. Our research population had an

older median age (67 years vs. 57 years). Our study also

covered a small number of patients with worse Eastern

Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (a score

of 2) [6.7%], whereas their study only included individuals

with a score of 0 to 1. Almost all of our patients (93.3%)

received bolus 5-FU as concurrent chemotherapy, with the

exception of one patient who received oral capecitabine,

compared to 78.1% of capecitabine patients in their

study.[8] Patients receiving prolonged 5-FU infusion had a

significantly longer time to relapse and improved survival

compared with bolus 5-FU.[11] Two randomised controlled

trials have shown that patients with rectal cancer who

received neoadjuvant or adjuvant capecitabine CRT

had non-inferior disease-free and OS when compared to

continuous 5-FU.[12] [13] Therefore, concurrent chemotherapy

with oral capecitabine should produce better outcomes

compared with bolus 5-FU. In addition, induction (7.0%)

and consolidation chemotherapy (30.8%) were used in

their research, which might further improve treatment

outcomes.[8]

Limitations

Our study had several limitations. First, it was a

retrospective study based on data from a single centre,

and this may add selection and information bias. Second,

our small sample size reduced the power of the study.

Despite a trend towards lower acute and chronic skin toxicity rates without inguinal RT, it did not reach

statistical significance. In light of the small number of

patients with inguinal RT and the retrospective nature

of the study, these results should be interpreted with

caution. Moreover, the elective inguinal RT group’s

small sample size may make it difficult to statistically

compare survival rates with those who did not receive

inguinal RT. Third, some baseline characteristics (i.e.,

baseline carcinoembryonic antigen level, clinical tumour

staging, and proportion of patients receiving neoadjuvant

vs. adjuvant radiation/chemoradiation therapy between

patients with or without elective inguinal irradiation)

were imbalanced, and this might create bias to the

interpretation of results. Lastly, as there was no uniform

follow-up imaging in our study population, survival

outcomes may have been overstated.

CONCLUSION

Omission of elective inguinal irradiation resulted in a

low inguinal failure rate and similar survival outcomes

for low rectal cancer patients with ACI. This study

demonstrated that the majority of inguinal recurrences

also had synchronous locoregional recurrence and/or distant failure, while isolated inguinal recurrences

were uncommon and could be salvaged by inguinal

dissection. These findings added to the body of evidence

supporting the omission of elective ILN irradiation

for this patient subgroup. Better-designed randomised

studies are warranted to define the role of elective

inguinal irradiation and to elucidate the best strategy for

treatment escalation.

REFERENCES

1. Li Y, Wang J, Ma X, Tan L, Yan Y, Xue C, et al. A review of neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy for locally advanced rectal cancer. Int J Biol Sci. 2016;12:1022-31. Crossref

2. Kachnic LA. Adjuvant chemoradiation for localized rectal cancer: current trends and future directions. Gastrointest Cancer Res. 2007;1(4 Suppl 2):S64-72.

3. Lee IK. The Lymphatic Spread of the Rectal Cancer. In: Kim NK, Sugihara K, Liang JT, editors. Surgical Treatment of Colorectal Cancer: Asian Perspectives on Optimization and Standardization.

Singapore: Springer; 2018. p 47-53. Crossref

4. Glynne-Jones R, Wyrwicz L, Tiret E, Brown G, Rödel C, Cervantes A, et al. Rectal cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2017;28(suppl_4):iv22-40. Crossref

5. Valentini V, Gambacorta MA, Barbaro B, Chiloiro G, Coco C, Das P, et al. International consensus guidelines on clinical target volume delineation in rectal cancer. Radiother Oncol.

2016;120:195-201. Crossref

6. Wo JY, Anker CJ, Ashman JB, Bhadkamkar NA, Bradfield L, Chang DT, et al. Radiation therapy for rectal cancer: executive

summary of an ASTRO Clinical Practice Guideline. Pract Radiat

Oncol. 2021;11:13-25. Crossref

7. Myerson RJ, Garofalo MC, El Naqa I, Abrams RA, Apte A, Bosch WR, et al. Elective clinical target volumes for conformal

therapy in anorectal cancer: a Radiation Therapy Oncology Group

consensus panel contouring atlas. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys.

2009;74:824-30. Crossref

8. Song M, Li S, Zhang Y, Geng J, Wang H, Zhu X, et al. Is elective inguinal or external iliac irradiation during neoadjuvant (chemo) radiotherapy necessary for locally advanced lower rectal cancer with anal sphincter invasion? Pract Radiat Oncol. 2022;12:125-34. Crossref

9. Taylor N, Crane C, Skibber J, Feig B, Ellis L, Vauthey JN, et al. Elective groin irradiation is not indicated for patients with adenocarcinoma of the rectum extending to the anal canal. Int J

Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2001;51:741-7. Crossref

10. Yeo SG, Lim HW, Kim DY, Kim TH, Kim SY, Baek JY, et al. Is elective inguinal radiotherapy necessary for locally advanced rectal adenocarcinoma invading anal canal? Radiat Oncol. 2014;9:296. Crossref

11. O’Connell MJ, Martenson JA, Wieand HS, Krook JE, Macdonald JS, Haller DG, et al. Improving adjuvant therapy for rectal cancer by combining protracted-infusion fluorouracil with radiation therapy after curative surgery. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:502-7. Crossref

12. Allegra CJ, Yothers G, O’Connell MJ, Beart RW, Wozniak TF, Pitot HC, et al. Neoadjuvant 5-FU or capecitabine plus radiation with or without oxaliplatin in rectal cancer patients: a phase III

randomized clinical trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;107:djv248. Crossref

13. Hofheinz RD, Wenz F, Post S, Matzdorff A, Laechelt S, Hartmann JT, et al. Chemoradiotherapy with capecitabine versus

fluorouracil for locally advanced rectal cancer: a randomised,

multicentre, non-inferiority, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol.

2012;13:579-88. Crossref

14. Lee WR, McCollough WM, Mendenhall WM, Marcus RB Jr, Parsons JT, Million RR. Elective inguinal lymph node irradiation for pelvic carcinomas. The University of Florida experience.

Cancer. 1993;72:2058-65. Crossref

15. Shiratori H, Nozawa H, Kawai K, Hata K, Tanaka T, Kaneko M, et al. Risk factors and therapeutic significance of inguinal lymph node metastasis in advanced lower rectal cancer. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2020;35:655-64. Crossref

16. Perez RO, Habr-Gama A, São Julião GP, Proscurshim I, Ono CR,

Lynn P, et al. Clinical relevance of positron emission tomography/computed tomography–positive inguinal nodes in rectal cancer after

neoadjuvant chemoradiation. Colorectal Dis. 2013;15:674-82. Crossref

17. Damin DC, Rosito MA, Schwartsmann G. Sentinel lymph node in carcinoma of the anal canal: a review. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2006;32:247-52. Crossref

18. Damin DC, Tolfo GC, Rosito MA, Spiro BL, Kliemann LM. Sentinel lymph node in patients with rectal cancer invading the

anal canal. Tech Coloproctol. 2010;14:133-9. Crossref

19. van der Pas MH, Meijer S, Hoekstra OS, Riphagen II, de Vet HC, Knol DL, et al. Sentinel-lymph-node procedure in colon and rectal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol.

2011;12:540-50. Crossref

20. Bahadoer RR, Dijkstra EA, van Etten B, Marijnen CA, Putter H,

Kranenbarg EM, et al. Short-course radiotherapy followed by

chemotherapy before total mesorectal excision (TME) versus

preoperative chemoradiotherapy, TME, and optional adjuvant

chemotherapy in locally advanced rectal cancer (RAPIDO): a

randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22:29-42. Crossref

21. Bujko K, Wyrwicz L, Rutkowski A, Malinowska M, Pietrzak L, Kryński J, et al. Long-course oxaliplatin-based preoperative chemoradiation versus 5 × 5 Gy and consolidation chemotherapy

for cT4 or fixed cT3 rectal cancer: results of a randomized phase

III study. Ann Oncol. 2016;27:834-42. Crossref

22. Conroy T, Bosset JF, Etienne PL, Rio E, François É, Mesgouez-Nebout N, et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy with FOLFIRINOX

and preoperative chemoradiotherapy for patients with locally

advanced rectal cancer (UNICANCER-PRODIGE 23): a

multicentre, randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol.

2021;22:702-15. Crossref

23. Jin J, Tang Y, Hu C, Jiang LM, Jiang J, Li N, et al. Multicenter, randomized, phase III trial of short-term radiotherapy plus chemotherapy versus long-term chemoradiotherapy in locally

advanced rectal cancer (STELLAR). J Clin Oncol. 2022;40:1681-92. Crossref

24. McCarthy K, Pearson K, Fulton R, Hewitt J. Pre-operative chemoradiation for non-metastatic locally advanced rectal cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;12:CD008368. Crossref