Magnetic Resonance Imaging–Guided Cryotherapy for Precision Tumour Ablation

ORIGINAL ARTICLE CME

Hong Kong J Radiol 2023 Sep;26(3):168-73 | Epub 2 Aug 2023

Magnetic Resonance Imaging–Guided Cryotherapy for Precision Tumour Ablation

JB Chiang, WL Poon, PCH Kwok, HS Fung

Department of Radiology and Imaging, Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

Correspondence: Dr JB Chiang, Department of Radiology and Imaging, Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China. Email: jbchian@gmail.com

Submitted: 10 Jun 2020; Accepted: 26 Aug 2020.

Contributors: JBC designed the study, acquired the data, analysed the data, and drafted the manuscript. All authors critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Funding/Support: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data Availability: All data generated or analysed during the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: This research was approved by the Kowloon Central/Kowloon East Cluster Research Ethics Committee of Hospital Authority, Hong Kong (Ref No.: KC/KE-20-0045/ER-4). Informed consent for treatment and procedures of this retrospective study was waived by the Committee.

Abstract

Introduction

Percutaneous ablation has played an increasingly prominent role in both palliative and curative treatment of solid tumours, allowing minimally invasive tumour destruction and pain control. Percutaneous ablation is frequently performed under ultrasound or computed tomography guidance, both of which are imperfect in delineating the ablation zone. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) guidance provides superior soft tissue contrast, real-time radiation-free imaging, and accurate visualisation of the ablation zone. This study aimed to describe the technique, assess its safety and benefits.

Methods

We retrospectively reviewed the clinical management of patients who had undergone MRI-guided ablation from 1 May 2019 to 31 January 2020 and collected patient data including tumour characteristics, procedure details, and follow-up imaging results.

Results

A total of 14 cases were analysed (10 renal cell carcinomas, 1 hepatocellular carcinoma, 1 adrenal metastasis, 1 external iliac lymph node metastasis, and 1 chest wall fibromatosis). All cases were technically successful with ice ball coverage of the tumour in line with operative intent. Three minor adverse events (two cases of frostbite and one perinephric haematoma) occurred. One patient declined follow-up imaging. Eleven patients showed no residual or recurrence; the patient with chest wall fibromatosis showed shrinkage of the lesion.

Conclusion

MRI guidance is safe and allows accurate tumour visualisation, real-time needle puncture for cryoprobe and hydrodissection needle insertion, and precise delineation of the ablation zone in many procedures.

Key Words: Ablation techniques; Carcinoma, renal cell; Cryosurgery; Magnetic resonance imaging, cine; Magnetic resonance imaging, interventional

中文摘要

磁共振引導精確腫瘤消融冷凍療法

蔣碧茜、潘偉麟、郭昶熹、馮漢盛

簡介

經皮消融可實現微創腫瘤消除和控制疼痛,在實體腫瘤的姑息性和根治性治療中正發揮愈趨重要的作用。經皮消融通常在超聲或電腦斷層引導下進行,兩者在劃定消融區方面都有局限性。磁共振引導具有明確優勢,它的軟組織對比度好,可實時無輻射成像,並可準確描繪消融區。本研究旨在描述該技術,評估其安全性和效益。

方法

我們對在2019年5月1日至2020年1月31日期間接受磁共振引導消融的患者臨床管理進行回顧性分析,並收集患者資料,包括腫瘤特徵、手術細節和隨訪影像檢查結果。

結果

本研究共分析了14例(腎細胞癌10例,肝細胞癌1例,腎上腺轉移1例,髂外淋巴結轉移1例及胸壁纖維瘤病1例)。所有病例均技術成功,冰球覆蓋腫瘤符合手術計劃。共發生3宗輕微副反應事件(2例凍傷及1例腎周血腫)。一名患者拒絕影像學隨訪。11例患者無殘留腫瘤或復發。胸壁纖維瘤病患者表現病灶縮小。

結論

磁共振引導安全,並且可以在許多手術中實現準確的腫瘤可視化、實時插入冷凍探針和水分離針,及精確描繪消融區域。

INTRODUCTION

Percutaneous tumour ablation is important in the

treatment of both benign and malignant diseases,

allowing minimally invasive treatment for tumour

destruction and pain control. Percutaneous tumour

ablation is frequently performed under ultrasound (US)

or computed tomography (CT) guidance, both of which

have significant limitations. For example, US provides

limited visualisation of deep structures and is readily

deflected by overlying gas and bone. CT, on the other

hand, emits radiation, rendering real-time needle insertion

unfavourable. Additionally, CT has limited soft tissue

spatial resolution, making it difficult if not impossible

to visualise the tumour and important surrounding

structures. Most importantly, both techniques of imaging

guidance do not allow accurate visualisation of ablation

zones.[1] Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) guidance

has swiftly achieved global prominence as it provides

superior soft tissue contrast, radiation-free real-time

imaging during needle insertion, and, most importantly,

clear visualisation of the ablation zone. Superior soft

tissue spatial resolution is particularly important as it

allows accurate visualisation of tumour and important

adjacent structures,[1] [2] which is otherwise difficult under

other imaging techniques. With these qualities, MRI

guidance allows safer, more precise, and radiation-free

imaging guidance of tumour ablation. Recently, the technique has been available in Hong Kong. The aim of

this retrospective single-institution study is to describe

the technique and evaluate its safety while highlighting

its use and benefits.

METHODS

Population

From 1 May 2019 to 31 January 2020, 14 patients (9

males, 5 females) underwent MRI-guided cryoablation

in our institution. Thirteen procedures were performed

on tumours with curative intent, and one as a staged

procedure to treat chest wall fibromatosis. Patients were

referred for local ablative treatment either because the

patient was not a suitable candidate for surgery or because

the lesions could not be treated by surgery (e.g., desmoid

tumours, bone metastases or lymph node metastases).

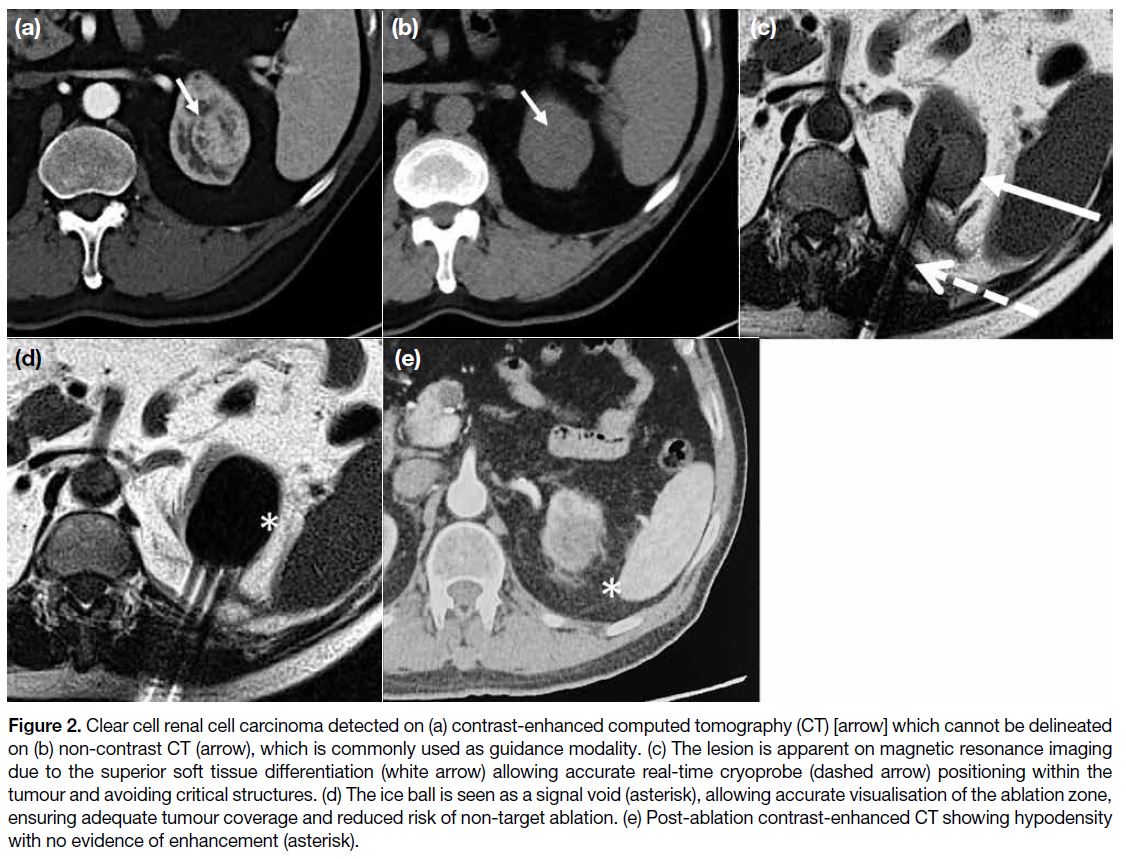

Patient and lesion characteristics are summarised in the

Table.

Table. Patient details and tumour characteristics

Magnetic Resonance Imaging–Guided Cryoablation

All interventions were performed in an MRI suite

dedicated to interventional procedures (Aera 1.5T;

Siemens Medical Systems, Erlangen, Germany) under

strict aseptic technique. Procedures were performed

under local lidocaine anaesthesia (n = 13) or general

anaesthesia (n = 1). Cryotherapy was performed with a cryoablation system (BTG Visual-ICE; Boston

Scientific, Marlborough [MA], United States) with one

or more cryoprobes (IceRod MRI or IceSeed MRI; Galil

Medical, Arden Hills [MN], United States) depending on

lesion characteristics, with manipulation of cryoprobes

to create different shapes and sizes of ablation zones,

often using the synergistic effects of multiple probes.

Cryoprobe insertion was performed under real-time

magnetic resonance fluoroscopic guidance using

a prototype interactive balanced steady-state free

precession sequence implemented for interactive realtime

tip tracking with interactive real-time tip tracking

module (BEAT IRTTT; Siemens Medical Systems,

Erlangen, Germany), which allows active adjustment

of scan plane orientation depending on the needs of

the operator. Occasionally, and particularly for ice ball

monitoring, multiplanar T2-weighted periodically rotated

overlapping parallel lines with enhanced reconstruction

(PROPELLER [periodically rotated overlapping

parallel lines with enhanced reconstruction]) or half-Fourier acquisition single-shot turbo spin-echo (HASTE)

sequences were acquired.

Tumour treatment was performed by ensuring that

the ablation zone included the entire tumour with an

additional safety margin of 5 to 10 mm. Treatment of the

chest wall fibromatosis was performed in this case as a staged procedure with partial coverage of the lesion for

size reduction.

Data Collection

Patient information on the Clinical Management System

of Hospital Authority from 1 May 2019 to 31 January

2020 was collected, which included patient age and

sex; target tumour type, location, size, and proximity to

important critical structures; procedure details including

mode of anaesthesia and need for hydrodissection;

complications; and duration of follow-up period. The size

of the target lesion is defined as the maximum diameter

on preprocedural MRI on the day of the procedure.

Complications were graded using the National Cancer

Instituteʼs Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse

Events (CTCAE) version 5.0. Patient outcome was

evaluated by postoperative imaging, on clinic visits,

and electronic medical records.

RESULTS

In total, 14 procedures were performed (10 renal cell

carcinomas, 1 hepatocellular carcinoma, 1 adrenal

metastasis, 1 external iliac lymph node metastasis,

and 1 chest wall fibromatosis) from 1 May 2019 to

31 January 2020 (Table). Mean age ± standard deviation

of the patients was 66 ± 14.3 years. Most procedures

(n = 13) were performed with curative intent; for these cases, mean tumour diameter was 1.6 ± 5.8 cm. One non-curative

procedure performed was a staged cryoablation

of chest wall fibromatosis measuring 24 cm, performed

for lesion size control.

All procedures performed with curative intent were

technically successful with adequate coverage of the

tumour observed during intraoperative MRI. For the

patient with cryoablation of chest wall fibromatosis

performed as a staged procedure, technical success was

achieved with coverage of the intended region of the

tumour. MRI-guided hydrodissection was performed in

two patients (14.3%) due to close proximity to the colon

(n = 1) and external iliac vessels (n = 1). A total of 85.7%

(12 out of 14) patients had two freeze/thaw cycles,

whereas 14.3% (2 out of 14) required three freeze/thaw cycles.

Three minor complications occurred. Two (14.3%)

developed CTCAE Grade 3 complications, both

developing a small area of frostbite at the needle insertion site, one of which developed before activation

of the freeze cycle. Both patients recovered after a minor

debridement. One patient (7%) developed a minor

perinephric haematoma (CTCAE Grade 1), which

recovered without intervention. No major complications

were observed.

The mean follow-up period was 7.2 ± 3.03 months.

One patient was lost to follow-up and excluded from

analysis. Of the patients with malignant disease (n = 12,

mean follow-up period = 7.6 months), tumour coverage

with no imaging evidence of residual or recurrence

was seen in 91.7% (n = 11). One patient with ablation

of an external iliac lymph node showed suspicious

fluorodeoxyglucose avidity in the iliac fossa on follow-up

positron emission tomography–CT, undetermined

but possibly residual disease. In the case of chest wall

fibromatosis, lesion size reduction was seen in the first

month after cryoablation. In this case, the disease that was

not cryoablated also showed interval shrinkage and is

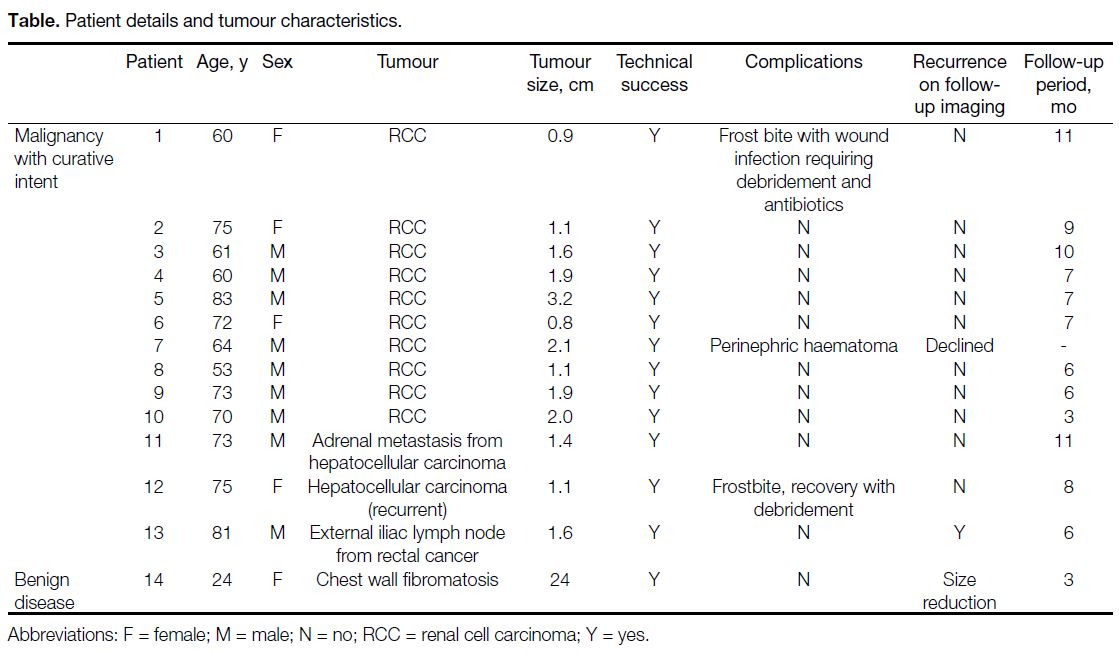

softer on palpation (Figure 1), attributed to abscopal effect. No other clinical complications, such as pain, were observed in any of the patients.

Figure 1. (a) Left chest wall fibromatosis (arrow) in a 24-year-old woman with a history of multiple prior resections with local recurrence. (b)

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showing the 10 cryoprobes that were inserted into the large mass (arrow). (c and d) The ice ball is clearly

identified as a signal void (asterisk) allowing accurate visualisation of the ablation zone. As the lesion was too large for complete ablation,

the procedure was performed with the goal of size reduction. (e) Post-ablation MRI 1 month after surgery showing a necrotic region (arrow)

with the non-ablated regions reduced in size, attributed to immune reaction from cryoablation. Clinically, the mass is softer on palpation.

DISCUSSION

Cryotherapy is a thermal ablative technique that

causes tumour destruction by inducing cell damage

by freezing and thawing. Current systems use argon

and helium gases delivered via cryoprobes that induce

freezing and thawing based on the Joule-Thomson effect

(temperature change as an effect of rapid expansion of

certain gases).[3] Cryoablation has advantages over other

ablation modalities such as radiofrequency ablation due

to its intrinsic analgesic effects and potential treatment

of large tumours.[4] Additionally, cryotherapy allows

visualisation of the ice ball, particularly under MRI,

which improves predictability of tumour coverage and

prevents non-target ablation.

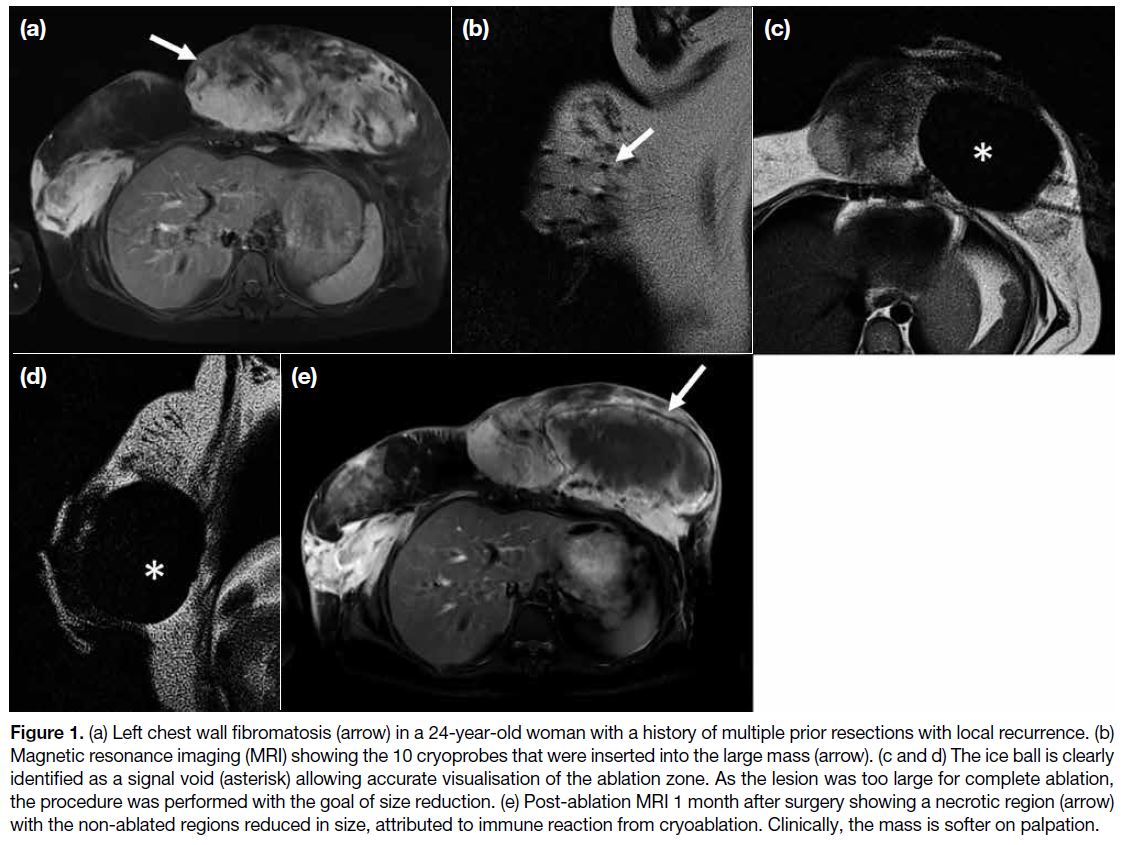

MRI is particularly useful in conjunction with

cryotherapy as it allows accurate visualisation of ice ball as a signal void[1] (Figure 2) as well as continuous

radiation-free multiplanar ice ball monitoring,[4] allowing

accurate assessment of ablation zone, which ensures

tumour coverage while avoiding non-target ablation.

Due to MRI’s superior soft-tissue differentiation, MRI

allows better tumour visualisation and hence improved

accuracy with needle positioning. Many lesions may only

be seen on MRI, such as non-exophytic renal masses or

hepatic dome lesions,[5] where MRI greatly improves the

accuracy of needle positioning.

Figure 2. Clear cell renal cell carcinoma detected on (a) contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) [arrow] which cannot be delineated on (b) non-contrast CT (arrow), which is commonly used as guidance modality. (c) The lesion is apparent on magnetic resonance imaging due to the superior soft tissue differentiation (white arrow) allowing accurate real-time cryoprobe (dashed arrow) positioning within the

tumour and avoiding critical structures. (d) The ice ball is seen as a signal void (asterisk), allowing accurate visualisation of the ablation zone, ensuring adequate tumour coverage and reduced risk of non-target ablation. (e) Post-ablation contrast-enhanced CT showing hypodensity

with no evidence of enhancement (asterisk).

MRI-guided intervention may be performed in an open- or

closed-bore system.[1] Open-bore systems allow easier

access to the patient and enhanced operator flexibility

but are limited by lower magnetic field strength

(0.2-1 T).[1] Closed-bore systems are more desirable

as they provide higher magnetic field strength, which

improves imaging rate and quality,[1] [2] [3] although at the

expense on operator comfort and flexibility. Such

systems have specific requirements to allow for interventional use, such as a large bore width (70 cm)

and short bore length (125-150 cm).[1] This is necessary

to allow the interventional radiologist to stretch into the

bore to work at the isocentre, allowing real-time freehand

manipulation. Additional body and surface coils may be

used to increase contrast resolution of images[6] but of all

the procedures described, the spine or body coil within

the magnet may suffice.

MRI-guided cryoablation has been described in the

literature as a treatment option for a variety of tumours.

Ahrar et al[2] described percutaneous cryotherapy of small

renal tumours in 18 patients in a 1.5-T MRI. The mean

follow-up period was 16.7 months, with rates of overall

survival, disease-specific survival, and metastasis-free

survival of 88.9%, 100%, and 100%, respectively.

Similarly, MRI-guided liver cryotherapy was described

to be safe and feasible. Mala et al[7] described percutaneous

cryoablation of six patients with liver metastases from

colorectal carcinoma using an open 0.5-T MRI, which

they concluded allowed good visualisation of tumour

for cryoprobe positioning in order to puncture the

tumour. Shimizu et al[8] treated 16 tumours with MRI-guided

cryoablation on a 0.3-T open-bore magnet with

1- and 3-year overall survival rates of 93.8% and 79.3%,

respectively. The complete ablation rate was reported as

80.8% at 3 years.

As the indications for ablation have expanded in both

malignant and benign tumours and with palliative and

curative intent, MRI guidance may be the preferred

imaging technique in certain lesions. MRI guidance

has proven beneficial for established ablation targets

including renal,[1] [2] [9] prostate,[1] [10] and soft tissue[1] tumours

such as desmoids. Although less established, we find

MRI guidance highly useful in liver ablation, especially

in recurrent tumours and lesions located in the hepatic

dome, as described by Wang et al.[5]

Limitations

This paper describes our early experience of MRI-guided

cryoablation with multiple shortcomings including a small sample size, short follow-up periods, and

heterogeneity of treated lesions. Existing studies have

mainly been retrospective analyses of cohorts of MRI or

CT guidance in heterogeneous patient groups; controlled

trials with larger sample sizes and comparison with other

methods of imaging guidance will be useful.

CONCLUSION

MRI guidance is a safe imaging technique that allows

accurate tumour and non-target organ visualisation,

real-time needle puncture, and precise delineation of the

ablation zone.

REFERENCES

1. Cazzato RL, Garnon J, Shaygi B, Tsoumakidou G, Caudrelier J, Koch G, et al. How to perform a routine cryoablation under MRI guidance. Top Magn Reson Imaging. 2018;27:33-8. Crossref

2. Ahrar K, Ahrar JU, Javadi S, Pan L, Milton DR, Wood CG, et al. Real-time magnetic resonance imaging–guided cryoablation of small renal tumors at 1.5 T. Invest Radiol. 2013;48:437-44. Crossref

3. Ahmed M, Brace CL, Lee FT Jr, Goldberg SN. Principles of and advances in percutaneous ablation. Radiology. 2011;258:351-69. Crossref

4. Cazzato RL, Garnon J, Ramamurthy N, Koch G, Tsoumakidou G, Caudrelier J, et al. Percutaneous image–guided cryoablation:

current applications and results in the oncologic field. Med Oncol. 2016;33:140. Crossref

5. Wang L, Liu M, Liu L, Zheng Y, Xu Y, He X, et al. MR-guided percutaneous biopsy of focal hepatic dome lesions with free-hand combined with MR fluoroscopy using 1.0-T open high-field

scanner. Anticancer Res. 2017;37:4635-41. Crossref

6. Ahrar JU, Stafford RJ, Alzubaidi S, Ahrar K. Magnetic resonance imaging–guided biopsy in the musculoskeletal system using a cylindrical 1.5-T magnetic resonance imaging unit. Top Magn

Reson Imaging. 2011;22:189-96. Crossref

7. Mala T, Edwin B, Samset E, Gladhaug I, Hol PK, Fosse E. Magnetic-resonance–guided percutaneous cryoablation of hepatic

tumours. Eur J Surg. 2001;167:610-7. Crossref

8. Shimizu T, Sakuhara Y, Abo D, Hasegawa Y, Kodama Y, Endo H. Outcome of MR-guided percutaneous cryoablation for hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2009;16:816-23. Crossref

9. Mogami T, Harada J, Kishimoto K, Sumida S. Percutaneous MR-guided cryoablation for malignancies, with a focus on renal cell carcinoma. Int J Clin Oncol. 2007;12:79-84. Crossref

10. King AJ, Dudderidge T, Darekar A, Schimitz K, Heard R, Everitt C. Establishing MRI-guided prostate intervention at a UK centre. Br J Radiol. 2019;92:20180918. Crossref

11. Moynagh MR, Kurup AN, Callstrom MR. Thermal ablation of bone metastases. Semin Intervent Radiol. 2018;35:299-308. Crossref