Kimura’s Disease Masquerading as Soft Tissue Sarcoma: a Case Report

CASE REPORT

Hong Kong J Radiol 2023 Jun;26(2):e5-9 | Epub 16 May 2023

Kimura’s Disease Masquerading as Soft Tissue Sarcoma: a Case Report

WM Yu1, WI Sit2, PY Chu1, KS Tse3

1 Department of Radiology and Organ Imaging, United Christian Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

2 Department of Radiology, Tung Wah Group of Hospitals, Hong Kong SAR, China

3 Department of Diagnostic and Interventional Radiology, Hong Kong Sanatorium & Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

Correspondence: Dr WM Yu, Department of Radiology and Organ Imaging, United Christian Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China. Email: ywm821@ha.org.hk

Submitted: 18 Apr 2022; Accepted: 5 Aug 2022.

Contributors: WMY designed the study. All authors acquired and analysed the data. WMY drafted the manuscript. All authors critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Funding/Support: This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data Availability: All data generated or analysed during the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee (Kowloon Central/Kowloon East Cluster) of Hospital Authority, Hong Kong (Ref No.: KC/KE-19-0169-ER-4). Written informed consent for all treatments, procedures and publication was obtained from the patients.

INTRODUCTION

Kimura’s disease is a rare idiopathic chronic inflammatory disease that predominantly affects young Asian males

with the head and neck region most affected.[1] [2] Disease

manifestation as upper extremity soft tissue masses is

extremely rare[3] with only sporadic cases reported. As

Kimura’s disease is a benign entity, it is important not

to misdiagnose these soft tissue masses as sarcomas. We

present two pathologically confirmed cases of Kimura’s

disease affecting the elbows with focus on the ultrasound

and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) features.

CASE REPORTS

Case 1

An 18-year-old man with good past health presented

with a 6-month history of bilateral painless soft tissue

elbow swellings and increased right neck swelling. He

had no constitutional symptoms, fever or itchiness.

Physical examination revealed a firm subcutaneous non-tender

mass over the medial aspect of each elbow up to

5 × 5 cm in size with no overlying skin changes or neurovascular deficit. Enlarged right neck lymph nodes

were also palpable. Laboratory tests revealed elevated

eosinophil count of 3.8 × 109/L (reference range,

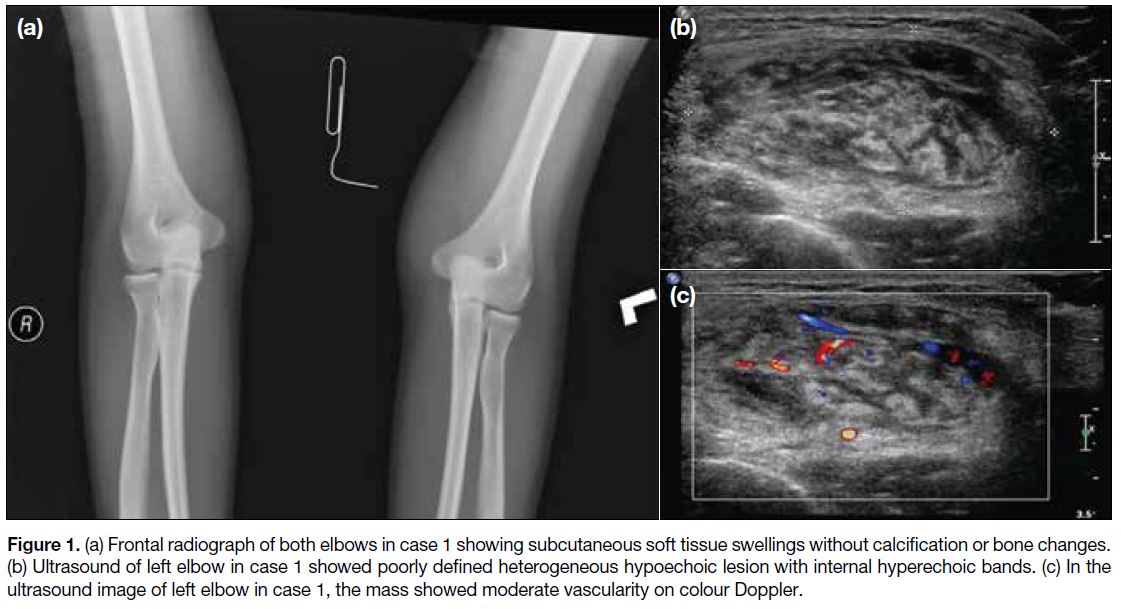

0-0.6 × 109/L). Radiograph (Figure 1a) demonstrated

soft tissue swelling at the medial aspect of both elbows

with no internal calcification or underlying bone change.

Ultrasound (Figure 1b and c) showed a poorly defined

heterogeneous hypoechoic mass in the subcutaneous

layer of the left elbow with curvilinear hyperechoic

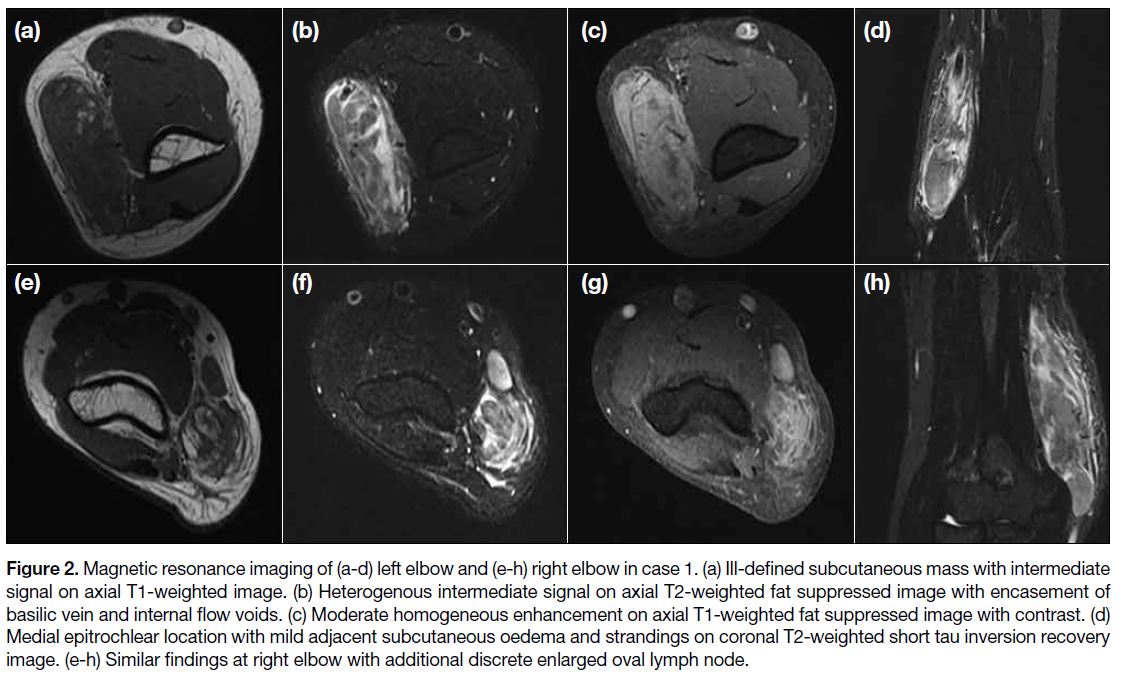

bands and moderate increased vascularity. MRI (Figure 2) showed ill-defined subcutaneous lesions at the medial

epitrochlear region of both elbows with extension to

mid humeri level. The lesions had an intermediate T1-weighted (T1W) signal, heterogeneous high signal on

T2-weighted (T2W) imaging relative to skeletal muscle

with moderate homogeneous enhancement and some

intralesional tubular flow voids. A few enlarged discrete

lymph nodes were identified and bilateral basilic veins

were encased by the lesions although patency was

maintained. There was no evidence of tumour necrosis

or cystic degeneration. Mild adjacent subcutaneous T2W hyperintense strandings, oedema, and enhancement

were also noted. No signs of muscular invasion or bone

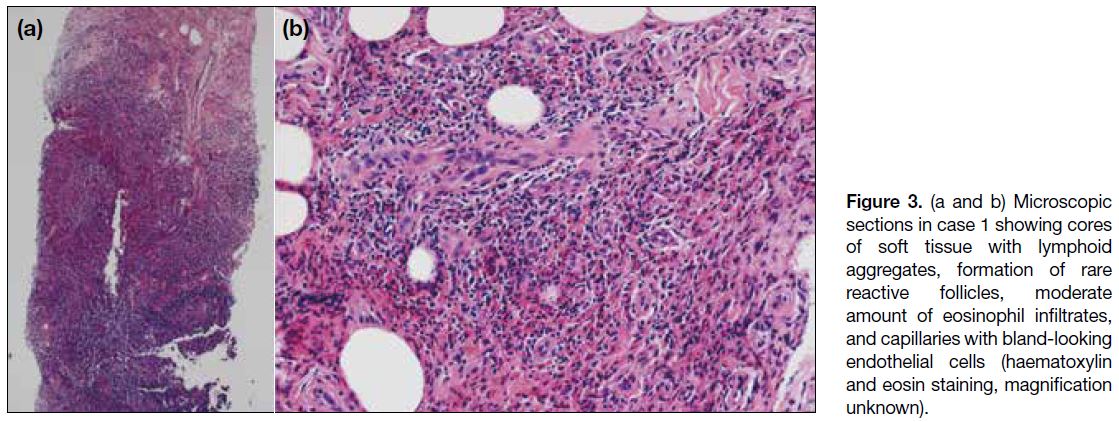

marrow oedema were evident. Ultrasound-guided core

biopsy of both elbow masses revealed a large amount

of lymphoid aggregates with eosinophilic infiltrates on a background of stromal fibrosis. Follicular hyperplasia,

formation of rare reactive follicles, proliferation of

endothelial venules, and perivenular sclerosis were

seen. No malignant cells, granuloma or Reed–Sternberg

cells were detected. Histopathology results (Figure 3) were suggestive of Kimura’s disease and the patient

subsequently underwent local excision of the left elbow

mass. Excisional biopsy result of the cervical lymph

nodes was also in keeping with Kimura’s disease.

Figure 1. (a) Frontal radiograph of both elbows in case 1 showing subcutaneous soft tissue swellings without calcification or bone changes.

(b) Ultrasound of left elbow in case 1 showed poorly defined heterogeneous hypoechoic lesion with internal hyperechoic bands. (c) In the

ultrasound image of left elbow in case 1, the mass showed moderate vascularity on colour Doppler.

Figure 2. Magnetic resonance imaging of (a-d) left elbow and (e-h) right elbow in case 1. (a) Ill-defined subcutaneous mass with intermediate

signal on axial T1-weighted image. (b) Heterogenous intermediate signal on axial T2-weighted fat suppressed image with encasement of

basilic vein and internal flow voids. (c) Moderate homogeneous enhancement on axial T1-weighted fat suppressed image with contrast. (d)

Medial epitrochlear location with mild adjacent subcutaneous oedema and strandings on coronal T2-weighted short tau inversion recovery

image. (e-h) Similar findings at right elbow with additional discrete enlarged oval lymph node.

Figure 3. (a and b) Microscopic sections in case 1 showing cores of soft tissue with lymphoid aggregates, formation of rare reactive follicles, moderate amount of eosinophil infiltrates, and capillaries with bland-looking endothelial cells (haematoxylin and eosin staining, magnification unknown).

Case 2

A 23-year-old man with good past health presented with

a 1-month history of a firm painless mass over his left

arm. He also complained of incidental left groin swelling.

There was no history of trauma. Physical examination

confirmed a 4 × 4 cm soft tissue mobile mass at left

posterior arm with no skin changes and a 3 × 4 cm non-pulsatile

mass of similar consistency at the left groin with

lack of cough impulse. An elevated eosinophil count of

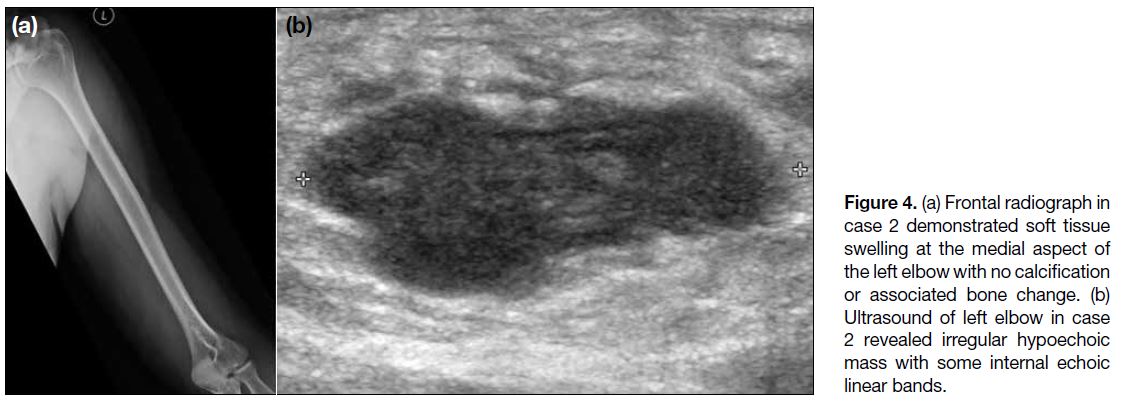

3.4 × 109/L (reference range, 0-0.6 × 109/L) was noted. Radiograph (Figure 4a) showed soft tissue swelling at

the medial aspect of his elbow with no calcification or

adjacent periosteal reaction. Ultrasound (Figure 4b)

revealed an irregular hypoechoic subcutaneous mass over the left elbow with a few internal hyperechoic

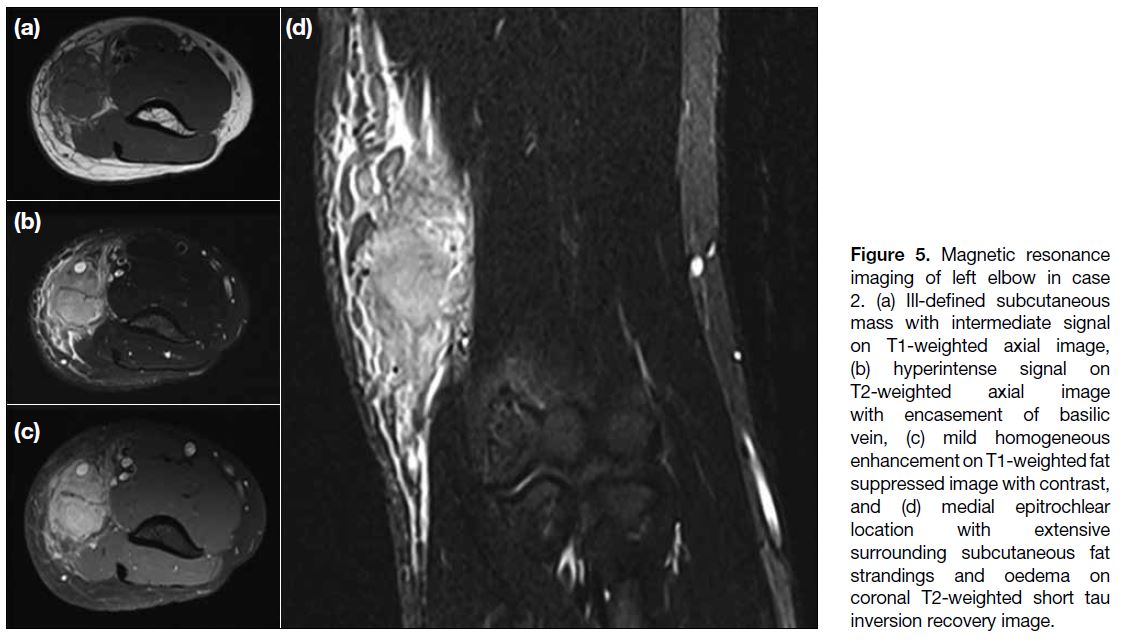

bands. MRI (Figure 5) showed an ill-defined T1W

isointense, T2W hyperintense subcutaneous mass with

homogeneous enhancement at the medial epitrochlear

region of the left elbow extending up to mid humerus

level. Marked adjacent subcutaneous oedema and

fluid together with interlobular septal thickening and

enhancement were seen. The basilic vein was encased

with preserved flow. Nearby musculature showed normal

signal and there was no bone marrow oedema. MRI of

the left groin demonstrated a cluster of enlarged lymph

nodes with marked subcutaneous strandings and oedema.

Ultrasound-guided biopsy of the elbow mass revealed

multiple reactive lymphoid follicles with germinal centre

formation, heavily infiltrated by eosinophils and bland-looking

lymphocytes. Occasional focal eosinophilic

microabscesses were seen and vasculature was slightly

prominent. Pathological features were suggestive of

Kimura’s disease. Core biopsy specimen taken from the left groin lymph node revealed similar findings. The patient was subsequently prescribed a course of oral steroid.

Figure 4. (a) Frontal radiograph in case 2 demonstrated soft tissue swelling at the medial aspect of the left elbow with no calcification or associated bone change. (b) Ultrasound of left elbow in case 2 revealed irregular hypoechoic mass with some internal echoic linear bands.

Figure 5. Magnetic resonance

imaging of left elbow in case 2. (a) Ill-defined subcutaneous mass with intermediate signal on T1-weighted axial image, (b) hyperintense signal on T2-weighted axial image with encasement of basilic vein, (c) mild homogeneous enhancement on T1-weighted fat suppressed image with contrast, and (d) medial epitrochlear location with extensive surrounding subcutaneous fat strandings and oedema on coronal T2-weighted short tau inversion recovery image.

DISCUSSION

Kimura’s disease is a rare chronic lymphoproliferative

disorder[1] first described by Kim and Szeto in 1937[4]

and later by Kimura et al in 1948[5]. It typically affects

Asians in their second or third decade of life[6] with a

higher incidence among males (male-to-female ratio

3:1). Typical presentation is painless subcutaneous

masses in the head and neck, particularly in the parotid

and submandibular regions. Other sites of involvement

include the oral cavity, axilla, groin, extremities, and

trunk. Symptoms have an insidious onset, may be

vague or asymptomatic and fluctuate for several years.[7]

Aetiology is unknown but there is speculation of an

underlying abnormal immune response.

Although imaging findings of Kimura’s disease in the

head and neck region have been previously reported

to be nonspecific and variable, consistent imaging

features are reported in Kimura’s disease of the upper

extremity.[7] [8] [9] To date, the largest published study of

imaging features of Kimura’s disease in the upper

extremity is by Choi et al[9] of nine cases. The authors

reported partial-to-poorly defined subcutaneous soft tissue masses at the medial epitrochlear region adjacent

to medial neurovascular bundles in all cases. The signal

intensity on T1W images was similar to or slightly

higher than that of muscle, while on T2W images, it was

markedly elevated compared to muscle. Enhancement

was at least moderately homogeneous. A variable

degree of surrounding subcutaneous fat strandings and

oedema as well as serpentine flow voids within the

masses were also reported. The masses usually caused

mass effect on surrounding muscles and encased

neurovascular structures without abnormal signal change

in the adjacent muscle, neurovascular bundles, bones

or joints.[9] Radiographs revealed only nonspecific soft

tissue thickening at the medial epitrochlear region with

no periosteal reaction or erosion in the adjacent bone.[9]

Shin et al[10] reported that ultrasound features of Kimura’s

disease in the upper extremities were of partially

marginated subcutaneous masses with the presence of

curvilinear hyperechoic bands and/or dots intermingled

within the hypoechoic components. Moderate to severe

vascular signals were observed in some of the hyperechoic

bands and/or dots on colour Doppler ultrasound. The

imaging findings and medial epitrochlear location in our

two cases were compatible with previous studies.

On histopathological examination, Kimura’s disease

characteristically demonstrates lymphoid follicular hyperplasia with prominent germinal centres, dense

eosinophilic infiltrates on a background of abundant

lymphoid and plasma cell infiltrates, eosinophilic

microabscesses, increased postcapillary venules and

perivenular sclerosis.[9] The vascular proliferation likely

accounts for the moderate enhancement and flow voids in

MRI, and the characteristic subcutaneous strandings and

oedema were histologically proven to be proliferation of

lymphoid follicles at subcutis.[9]

In both of our cases, there was concurrent involvement

of either cervical or groin lymph nodes. Bilateral

elbow involvement was also demonstrated in one case.

To the best of our knowledge, there have been only

four reported cases of bilateral upper limb Kimura’s

disease.[5] [7] [8] [10] These suggest that Kimura’s disease is

a systemic disease rather than a locoregional disorder.

Other reasons include frequent elevated level of serum

immunoglobulin E, peripheral blood eosinophilia,

generalised lymphadenopathy, and occasional renal

involvement.[11]

Differential diagnoses include tuberculous

lymphadenopathy, cat-scratch disease, angiolymphoid

hyperplasia with eosinophilia (ALHE), nodular fasciitis,

lymphoma, metastatic disease, and soft tissue sarcomas.[12]

Tuberculous involvement of lymph nodes would give

a matted appearance with central necrosis. Cat-scratch

disease similarly affects the medial epitrochlear region

but there would also be a contact history, painful

swelling, necrotic nodes, positive serology, and more

extensive subcutaneous oedema and strandings. It is

difficult to differentiate ALHE from Kimura’s disease

on imaging but when examined through histopathology,

ALHE does not show elements of fibrosis or sclerosis

that are evident universally in Kimura’s disease. Nodular

fasciitis presents with rapidly growing painful nodules

showing broad fascial contact but Kimura’s disease is

usually painless. Lymphoma often demonstrates bilateral

enlargement of well-defined nodes without changes to

subcutaneous fat. Metastatic lymph nodes classically

show loss of central fatty hilum, internal necrosis,

and capsular vascularity. Soft tissue sarcoma usually

manifests as a large circumscribed heterogeneous mass

with necrosis and some may show calcification. Kimura’s

disease tends to have poor margins, lack of necrosis, and

absence of calcification.

Management of Kimura’s disease is controversial and

options range from medical therapy with steroids or cytotoxic drugs to radiotherapy or surgical excision.[13] Surgery is the treatment of choice for a single, well-defined

lesion and has the benefit of pathological

confirmation. Conservative management is reserved for

those with recurrent disease and systemic involvement.

Although Kimura’s disease has an excellent prognosis

with no risk of malignant transformation, the recurrence

rate is around 25% to 75% after surgery.[7]

In conclusion, the diagnosis of Kimura’s disease requires pathological confirmation and upper limb manifestation

is rare. Nonetheless presence of the characteristic

imaging appearance along with peripheral eosinophilia

in a young Asian male should always raise a suspicion

of Kimura’s disease. The systemic nature of this entity

warrants a meticulous physical examination and imaging

to look for generalised lymphadenopathy and bilateral

involvement.

REFERENCES

1. Kase Y, Ikeda T, Yamane M, Ichimura K, Iinuma Y. Kimura’s disease: report of 4 cases with a review of 130 reported cases. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1990;63:413-8.

2. Li TJ, Chen XM, Wang SZ, Fan MW, Semba I, Kitano M. Kimura’s disease: a clinicopathologic study of 54 Chinese patients. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1996;82:549-55. Crossref

3. Lam AC, Au Yeung RK, Lau VW. A rare disease in an atypical location—Kimura’s disease of the upper extremity. Skeletal Radiol. 2015;44:1833-7. Crossref

4. Kim HT, Szeto C. Eosinophilic hyperplastic lymphogranuloma. Comparison with Mikulicz’s disease. Chin Med J. 1937;23:699-700.

5. Kimura T, Yoshimura S, Ishikawa E. On the unusual granulation combined with hyperplastic changes of lymphatic tissue. Trans Soc Pathol Jpn. 1948;37:179-80.

6. Ginsberg LE, McBride JA. Kimura’s disease. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1998;171:1508. Crossref

7. Park JS, Jin W, Ryu KN, Won KY. Bilateral asymmetric superficial soft tissue masses with extensive involvement of both upper extremities: demonstration of Kimura’s disease by US and MRI

(2008: 12b). Eur Radiol. 2009;19:781-6. Crossref

8. Huang GS, Lee HS, Chiu YC, Yu CC, Chen CY. Kimura’s disease of the elbows. Skeletal Radiol. 2005;34:555-8. Crossref

9. Choi JA, Lee GK, Kong KY, Hong SH, Suh JS, Ahn JM, et al. Imaging findings of Kimura’s disease in the soft tissue of the upper extremity. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005;184:193-9. Crossref

10. Shin GW, Lee SJ, Choo HJ, Park YM, Jeong HW, Lee SM, et al. Ultrasonographic findings of Kimura’s disease presenting in the upper extremities. Jpn J Radiol. 2014;32:692-9. Crossref

11. Wang TF, Liu SH, Kao CH, Chu SC, Kao RH, Li CC. Kimura’s disease with generalized lymphadenopathy demonstrated by positron emission tomography scan. Intern Med. 2006;45:775-8. Crossref

12. Chokkappan K, Al-Riyami AM, Krishnan V, Min VL. Unusual cause of swelling in the upper limb: Kimura disease. Oman Med J. 2015;30:372-7. Crossref

13. Takeishi M, Makino Y, Nishioka H, Miyawaki T, Kurihara K. Kimura disease: diagnostic imaging findings and surgical treatment. J Craniofac Surg. 2007;18:1062-7. Crossref