Hysterosalpingographic Findings from Uterus to Peritoneal Cavity: A Pictorial Essay

PICTORIAL ESSAY

Hong Kong J Radiol 2023 Jun;26(2):153-60 | Epub 8 May 2023

Hysterosalpingographic Findings from Uterus to Peritoneal Cavity: A Pictorial Essay

SC Wong, KS Yung, RLS Chan, WH Luk

Department of Radiology, Princess Margaret Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

Correspondence: Dr Dr SC Wong, Department of Radiology, Princess Margaret Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China. Email: wsc696@ha.org.hk

Submitted: 7 Jun 2021; Accepted: 3 Aug 2021.

Contributors: All authors designed the study, acquired the data, and analysed the data. SCW drafted the manuscript. All authors critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Funding/Support: This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data Availability: All data generated or analysed during the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: This study was approved by the Kowloon West Cluster Research Ethics Committee of Hospital Authority, Hong Kong [Ref No.: KW/EX-21-108(161-08)]. Patient consent was waived by the Committee.

BACKGROUND

With social trends of late marriage and increasing maternal age, there is ongoing demand for assisted reproduction

and subfertility investigations. Since tubal occlusion is

an important cause of female subfertility,[1] assessment of

tubal patency is a crucial part of investigations to identify

the cause of subfertility.

Hysterosalpingography (HSG) is a fluoroscopic

examination of the uterus and fallopian tubes with

contrast instillation through the cervical canal. It has

remained a popular investigation of tubal patency in

modern reproductive medicine despite being invented

more than 100 years ago.[2] It is considered a standard

first-line test for assessment of tubal patency[3] [4] in view

of its reliability, less invasiveness than laparoscopy, and

more efficient use of medical resources.[4]

With age-related fertility decline,[4] expeditious

management is essential. Severity of tubal disease

identified on HSG guides the management decision

for intervention.[5] A finding of bilateral tubal occlusion

prompts early referral for consideration of in vitro

fertilisation. Detection of uterine cavity or contour

abnormalities on HSG can guide further imaging, endoscopic investigations, and intervention. A

radiologist’s familiarity with HSG interpretation and

awareness of the spectrum of pathology is advantageous

to overall patient care and outcome.

This article presents a pictorial review of HSG cases with emphasis on a spectrum of pathologies including tubal

occlusion, tuboperitoneal pathologies, uterine contour

anomalies, and intracavity filling defects.

PERFORMING HYSTEROSALPINGOGRAPHY

Prior to instrumentation of the uterine cavity, exclusion of pregnancy and active pelvic infection are of utmost

importance.

The optimal time to perform HSG is between day 7 and

12 of the menstrual cycle.[6] This helps avoid pregnancy

and improve image interpretation with the thinner

endometrium of the early proliferative phase. Conducting

the examination during active menstruation may impair

assessment of the endometrial cavity configuration.

Contrast injection into an already distended uterine

cavity during active heavy menstruation may also cause

unnecessary patient discomfort.

The patient should be positioned in a lithotomy position

for pelvic examination. Aseptic technique with cleansing

and draping of the perineum, speculum examination to

expose the cervical os, followed by cleansing of the

ectocervix and vagina are mandatory before catheter

insertion to minimise the risk of ascending infection.

Different catheters can be used for an HSG, including

infant Foley catheter (8 Fr) or commercially available

HSG 5F catheters (CooperSurgical, Trumbull [CT],

United States). In our institution, an 8-Fr infant Foley

catheter and water-soluble contrast (such as iohexol or

iodixanol) are used.

Flushing of the Foley catheter and all extension tubes

to eliminate dead space before catheterisation will

help reduce introduction of air bubbles into the uterus.

Catheter insertion followed by slow gentle inflation of the

balloon (around 1-3 mL of water) to secure the catheter

is required. Nulliparous patients generally tolerate a

lower volume of balloon distension than patients with

prior pregnancy.

With successful catheterisation, the patient is repositioned

supine for fluoroscopic examination. The standard

views in HSG are based on the recommendations of the

American College of Radiology’s Practice Parameter for

the Performance of Hysterosalpingography.[6] [7] Chapman

& Nakielny’s Guide to Radiological Procedures[8] is also

in consensus with the above references.

Based on the above recommendations, the standard set

in each HSG study should contain four images: (1) early

uterine filling (to assess small uterine filling defects);

(2) late uterine filling and tubal filling (to assess uterine

contour and tubal abnormalities); (3) peritoneal spillage

(to document tubal patency), and (4) an image taken after

Foley balloon deflation and catheter removal (to assess

the lower uterine segment and endocervical canal).

If tubal occlusion is suspected, manoeuvres such as

delayed screening, decubitus position, and use of

spasmolytic agents (glucagon or hyoscine butylbromide)

should be performed in an attempt to determine if it is

genuine.

HYSTEROSALPINGOGRAPHIC FINDINGS

Normal Anatomy

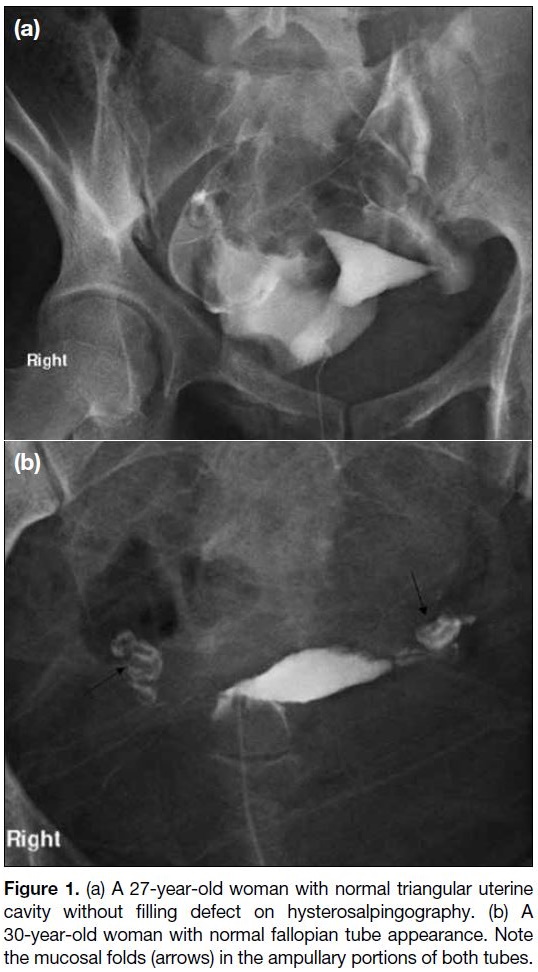

The uterine cavity has a well-defined smooth border with

inverted triangular shape and no persistent filling defect (Figure 1a). The fallopian tubes are evident as thin,

elongated smooth lines with a widening at the ampullary

portion and variable pelvic location.[6] Opacification

of the ampullary portion of the fallopian tube can be

confirmed by visualisation of mucosal folding (Figure 1b).[6] Free peritoneal contrast spillage from the fimbrial

end indicates tubal patency.

Figure 1. (a) A 27-year-old woman with normal triangular uterine

cavity without filling defect on hysterosalpingography. (b) A

30-year-old woman with normal fallopian tube appearance. Note

the mucosal folds (arrows) in the ampullary portions of both tubes.

Tubal Pathology

Non-opacification of the fallopian tube or absence of

peritoneal contrast spillage can be due to cornual smooth

muscle spasm or genuine tubal pathology. The sensitivity

and specificity of assessing bilateral tubal patency or

occlusion on HSG has been reported to be 92.1% and

85.7%, respectively.[9] There is no published consensus on

the most effective manoeuvre to relieve cornual spasm. Laparoscopy is considered as the traditional clinical

reference standard for diagnosis of tubal disease.[5] [9]

Chromotubation of the fallopian tubes with contrast dye

injection and visualisation of peritoneal dye spillage

provides assessment of tubal patency.

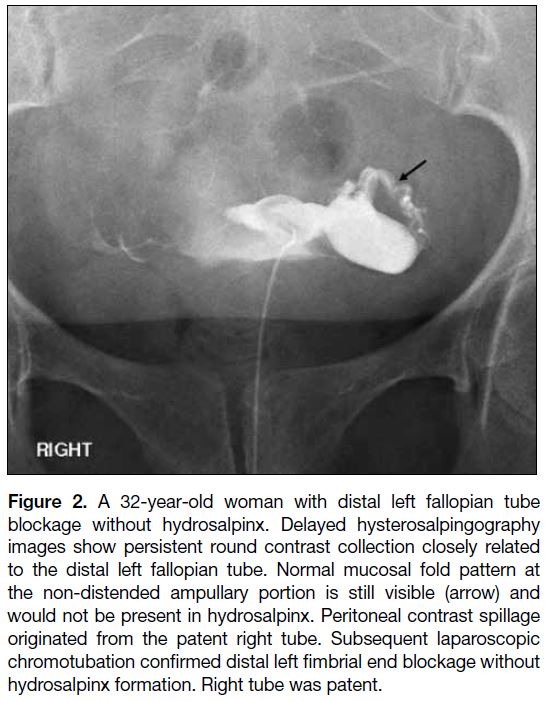

Tubal Occlusion

Tubal occlusion manifests as abrupt transition from

the contrast-filled proximal fallopian tube to a non-opacified

distal portion and absent peritoneal contrast

spillage (Figure 2). Tubal occlusion can be due to pelvic

adhesions from prior pelvic inflammatory disease,

endometriosis, or less commonly to congenital Müllerian

duct malformation.[6] [10]

Figure 2. A 32-year-old woman with distal left fallopian tube

blockage without hydrosalpinx. Delayed hysterosalpingography

images show persistent round contrast collection closely related

to the distal left fallopian tube. Normal mucosal fold pattern at

the non-distended ampullary portion is still visible (arrow) and

would not be present in hydrosalpinx. Peritoneal contrast spillage

originated from the patent right tube. Subsequent laparoscopic

chromotubation confirmed distal left fimbrial end blockage without

hydrosalpinx formation. Right tube was patent.

Tuboperitoneal Pathologies

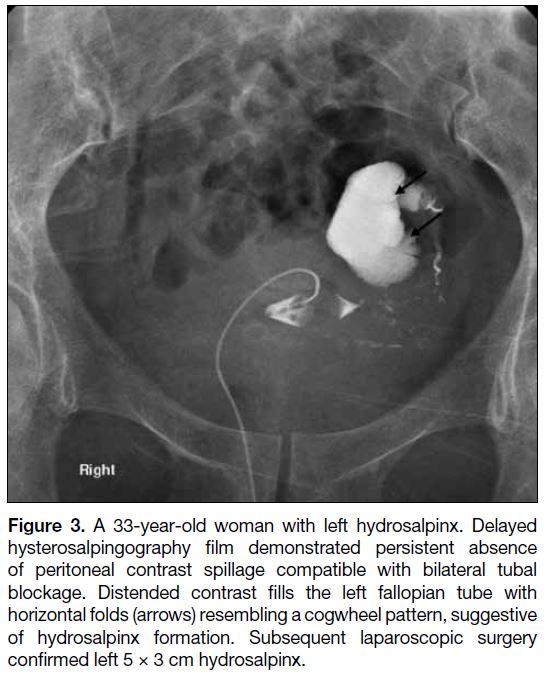

Hydrosalpinx

Hydrosalpinx represents a distended fallopian tube with

serous fluid accumulation secondary to tubal blockage

(Figure 3).[11] It is associated with pelvic inflammatory

disease, endometriosis, or prior tubal surgery (e.g.,

ligation), tubal pregnancy or rarely tubal malignancy. On

HSG, hydrosalpinx manifests as contrast-filled dilated

fallopian tubes without distal contrast spillage into the

peritoneal cavity.[6]

Figure 3. A 33-year-old woman with left hydrosalpinx. Delayed

hysterosalpingography film demonstrated persistent absence

of peritoneal contrast spillage compatible with bilateral tubal

blockage. Distended contrast fills the left fallopian tube with

horizontal folds (arrows) resembling a cogwheel pattern, suggestive

of hydrosalpinx formation. Subsequent laparoscopic surgery

confirmed left 5 × 3 cm hydrosalpinx.

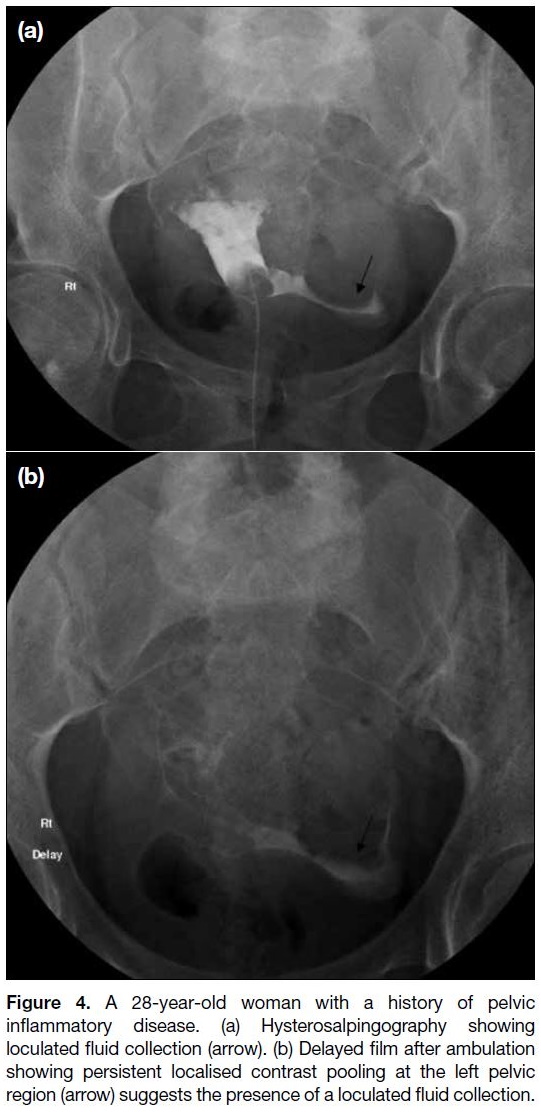

Peritubal adhesion and pelvic peritoneal loculated

collections

Pelvic inflammatory disease can result in pelvic and

peritoneal scarring and consequent adhesion bands

around the pelvic organs.[11] Adhesions around the

fallopian tubes can result in tubal blockage with loculated

contrast collections.[6] A loculated pelvic collection can

manifest as a persistent localised contrast-filled region in

delayed screening on HSG (Figure 4).

Figure 4. A 28-year-old woman with a history of pelvic

inflammatory disease. (a) Hysterosalpingography showing

loculated fluid collection (arrow). (b) Delayed film after ambulation

showing persistent localised contrast pooling at the left pelvic

region (arrow) suggests the presence of a loculated fluid collection.

Salpingitis isthmica nodosa

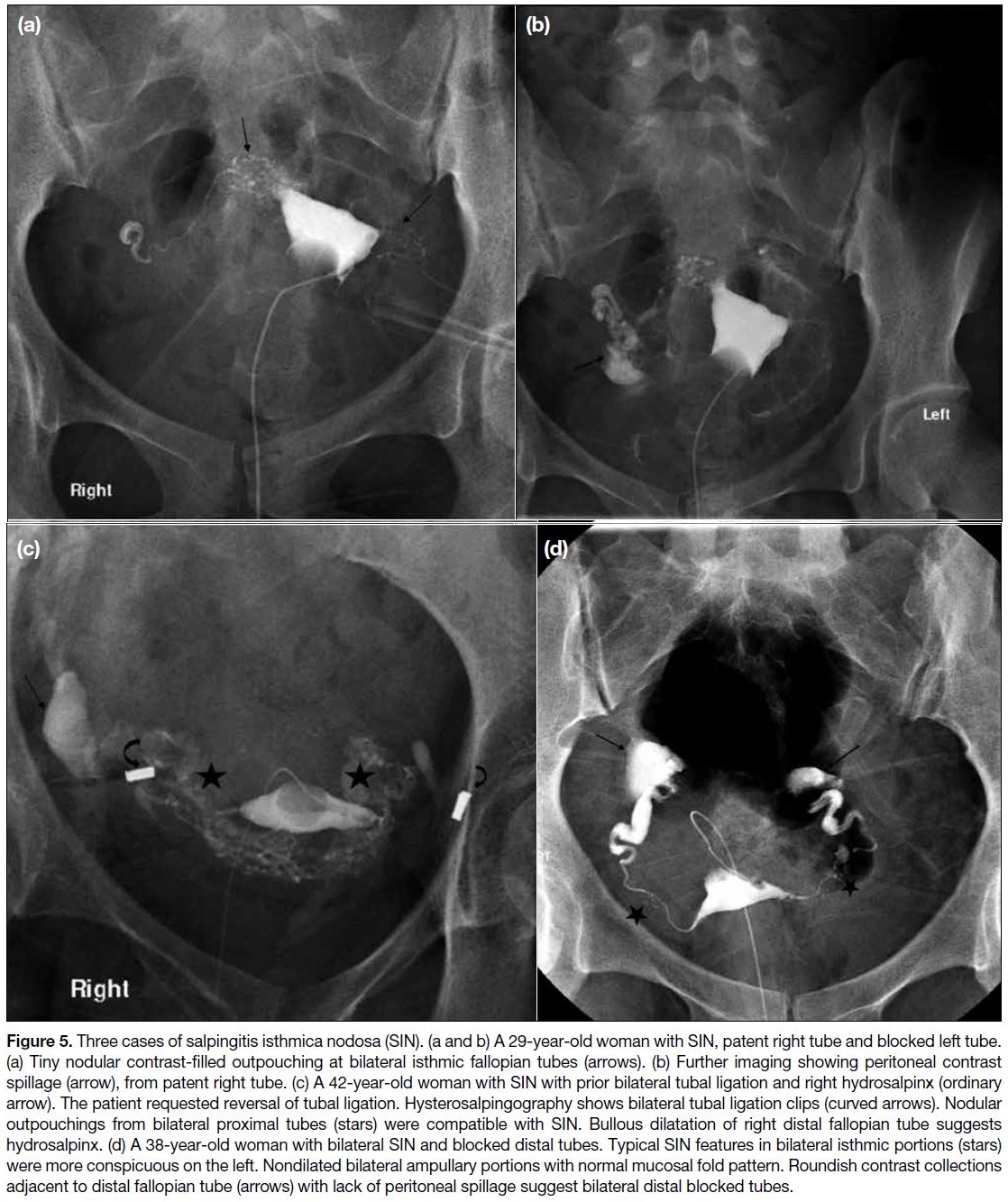

Salpingitis isthmica nodosa (SIN) is a fallopian tube

disease of unknown aetiology that is characterised by

proximal tubal (isthmic portion) nodular thickening,

associated diverticulosis of isthmic tubal epithelium

invading into the muscular layer with secondary smooth

muscle hypertrophy, and preserved smooth serosal

surface (Figure 5).[12] Features are more often bilateral than

unilateral. The reported incidence of SIN is 0.6% to 11%

in healthy fertile females with a strong association with

infertility and ectopic pregnancy.[13] Although SIN can

be diagnosed on HSG from its distinctive appearance,

histological proof is the gold standard.[12] The presence of

nodular outpouchings along the cornual isthmic portions

of fallopian tubes on HSG represents contrast-filled tubal

diverticula.[6] [10] The tubal outpouchings may measure up to 2 cm.[12]

Figure 5. Three cases of salpingitis isthmica nodosa (SIN). (a and b) A 29-year-old woman with SIN, patent right tube and blocked left tube.

(a) Tiny nodular contrast-filled outpouching at bilateral isthmic fallopian tubes (arrows). (b) Further imaging showing peritoneal contrast

spillage (arrow), from patent right tube. (c) A 42-year-old woman with SIN with prior bilateral tubal ligation and right hydrosalpinx (ordinary

arrow). The patient requested reversal of tubal ligation. Hysterosalpingography shows bilateral tubal ligation clips (curved arrows). Nodular

outpouchings from bilateral proximal tubes (stars) were compatible with SIN. Bullous dilatation of right distal fallopian tube suggests

hydrosalpinx. (d) A 38-year-old woman with bilateral SIN and blocked distal tubes. Typical SIN features in bilateral isthmic portions (stars)

were more conspicuous on the left. Nondilated bilateral ampullary portions with normal mucosal fold pattern. Roundish contrast collections

adjacent to distal fallopian tube (arrows) with lack of peritoneal spillage suggest bilateral distal blocked tubes.

Uterine Cavity Contour Abnormalities

Uterine cavity contour abnormalities can be categorised

as uterine cavity outpouching or extrinsic indentation

or irregular outline (that can be associated with prior

surgery, infection or inflammation).

Contour outpouchin

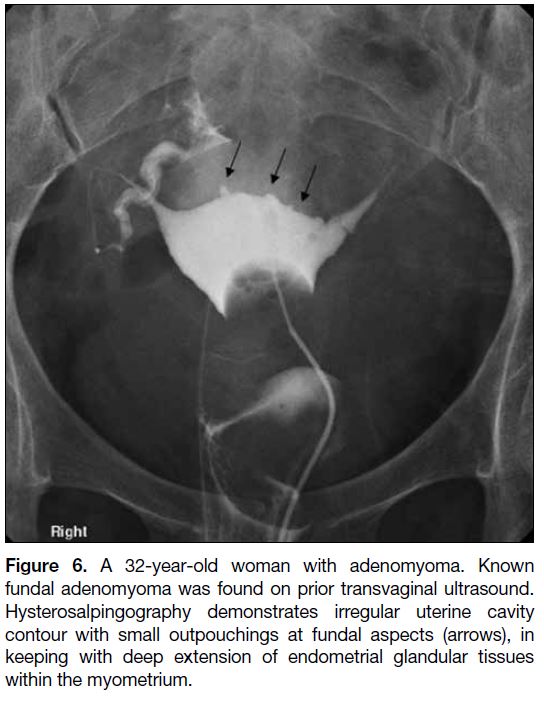

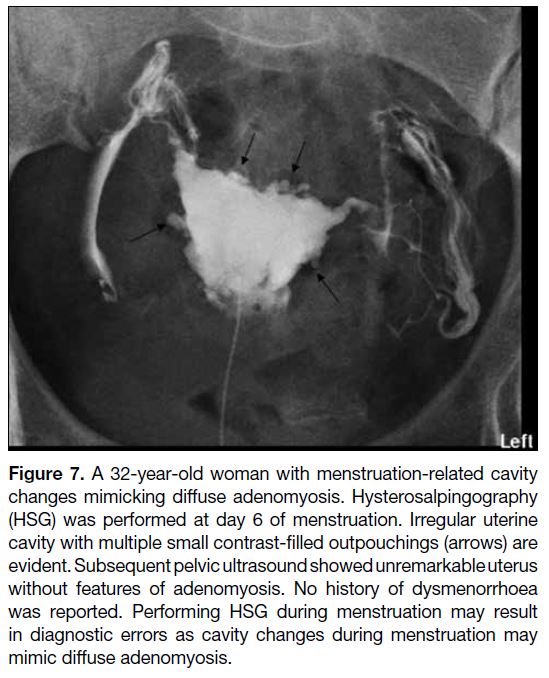

Adenomyosis is the extension of endometrial glandular

tissue into the myometrium and can be diffuse or focal

in extent (Figure 6). When regions of endometrial glands

are connected to the uterine cavity, they can become opacified on HSG study and show as diverticula or

outpouchings in the uterine cavity.[6] Further imaging

with ultrasound or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

allows confirmation of the diagnosis and visualisation of

the extent of adenomyotic changes. Differentiation with

irregular cavity outline may be encountered if HSG is

performed during menstruation (Figure 7).

Figure 6. A 32-year-old woman with adenomyoma. Known

fundal adenomyoma was found on prior transvaginal ultrasound.

Hysterosalpingography demonstrates irregular uterine cavity

contour with small outpouchings at fundal aspects (arrows), in

keeping with deep extension of endometrial glandular tissues

within the myometrium.

Figure 7. A 32-year-old woman with menstruation-related cavity

changes mimicking diffuse adenomyosis. Hysterosalpingography

(HSG) was performed at day 6 of menstruation. Irregular uterine

cavity with multiple small contrast-filled outpouchings (arrows) are

evident. Subsequent pelvic ultrasound showed unremarkable uterus

without features of adenomyosis. No history of dysmenorrhoea

was reported. Performing HSG during menstruation may result

in diagnostic errors as cavity changes during menstruation may

mimic diffuse adenomyosis.

Uterine contour indentation

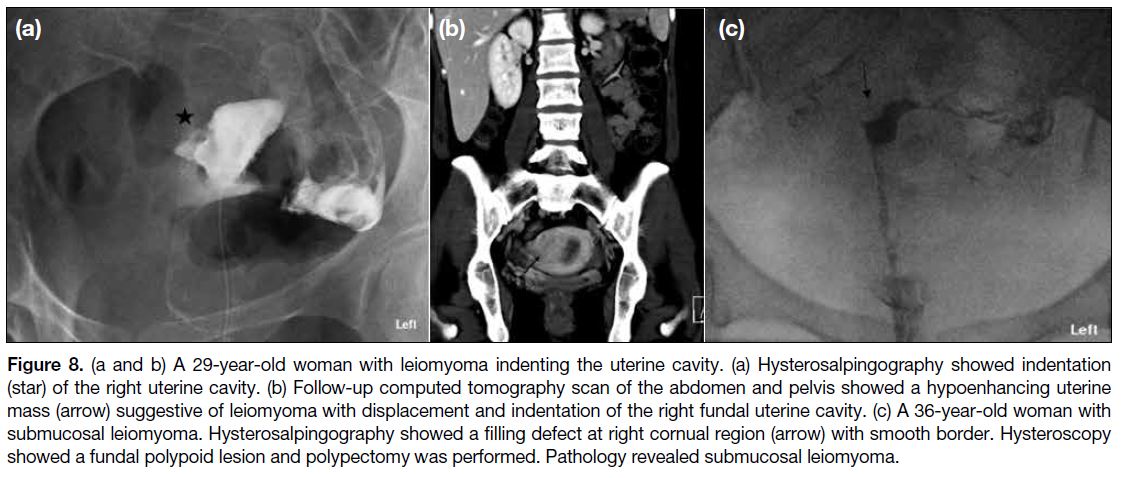

Leiomyoma is a benign tumour composed of uterine

smooth muscle (Figure 8). Sizable leiomyoma,

especially at a submucosal location, may be evidenced

by smooth indentation of the uterine cavity with cavity

distortion on HSG.[6] [10] Distorted endometrial cavity

contour may contribute to subfertility owing to changes

in endometrial receptivity, development, and hormone

environment.[10]

Figure 8. (a and b) A 29-year-old woman with leiomyoma indenting the uterine cavity. (a) Hysterosalpingography showed indentation

(star) of the right uterine cavity. (b) Follow-up computed tomography scan of the abdomen and pelvis showed a hypoenhancing uterine

mass (arrow) suggestive of leiomyoma with displacement and indentation of the right fundal uterine cavity. (c) A 36-year-old woman with

submucosal leiomyoma. Hysterosalpingography showed a filling defect at right cornual region (arrow) with smooth border. Hysteroscopy

showed a fundal polypoid lesion and polypectomy was performed. Pathology revealed submucosal leiomyoma.

Intracavity Filling Defects

Sensitivity of HSG in detecting intrauterine abnormalities

has been reported to be about 58.2%, compared with 82%

for ultrasonography.[10] Intracavity filling defects can be

artefactual and due to air bubbles or intracavity pathology

such as endometrial polyps, intracavity leiomyoma, or

synechiae. Persistent and stationery filling defects are

more suspicious of intracavity pathology. Preprocedural

flushing of the catheter helps minimise the chance of air

bubble contamination.

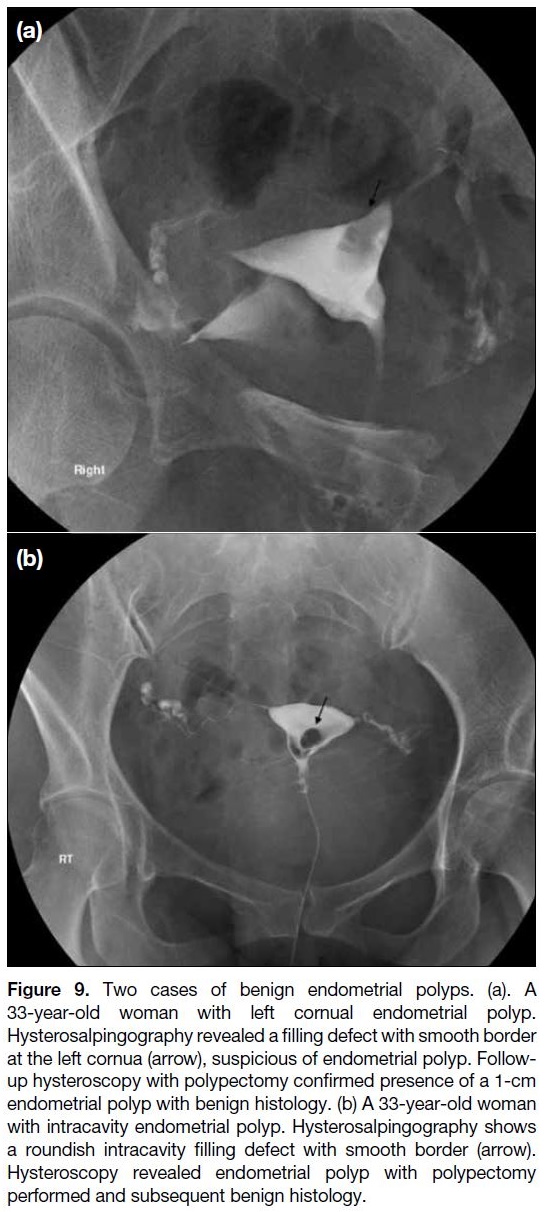

Endometrial polyps

Endometrial polyps are benign focal proliferations

of endometrial tissue, usually seen as smooth oval

to roundish filling defects on HSG (Figure 9). Saline

infusion sonohysterography with ultrasound assessment

after saline instillation into the uterine cavity can help

distinguish the causes of an intracavity filling defect

with superior accuracy for endometrial polyps than

transvaginal ultrasound or HSG.[14] Hysteroscopy is

the gold standard for diagnosis[14] and can be applied

to provide therapeutic treatment with polypectomy or

adhesiolysis.

Figure 9. Two cases of benign endometrial polyps. (a). A

33-year-old woman with left cornual endometrial polyp.

Hysterosalpingography revealed a filling defect with smooth border

at the left cornua (arrow), suspicious of endometrial polyp. Follow-up

hysteroscopy with polypectomy confirmed presence of a 1-cm

endometrial polyp with benign histology. (b) A 33-year-old woman

with intracavity endometrial polyp. Hysterosalpingography shows

a roundish intracavity filling defect with smooth border (arrow).

Hysteroscopy revealed endometrial polyp with polypectomy

performed and subsequent benign histology.

Synechiae

Intrauterine adhesions or synechiae result from insult

to the basal endometrial lining, such as prior surgery

(especially dilatation and curettage) or endometritis

(Figure 10). Asherman’s syndrome is the presence

of intrauterine adhesions with clinical manifestations

of abnormal menstruation (e.g., amenorrhoea/hypomenorrhoea) and subfertility.[6] On HSG, adhesions

are more often linear, irregular or angulated.

Figure 10. A 38-year-old woman with uterine synechiae with

Asherman’s syndrome. Intracavity irregular angulated filling defect

was observed on hysterosalpingography (arrow), confirmed by

subsequent hysteroscopy with adhesiolysis performed.

Variant Anatomy or Congenital Malformation

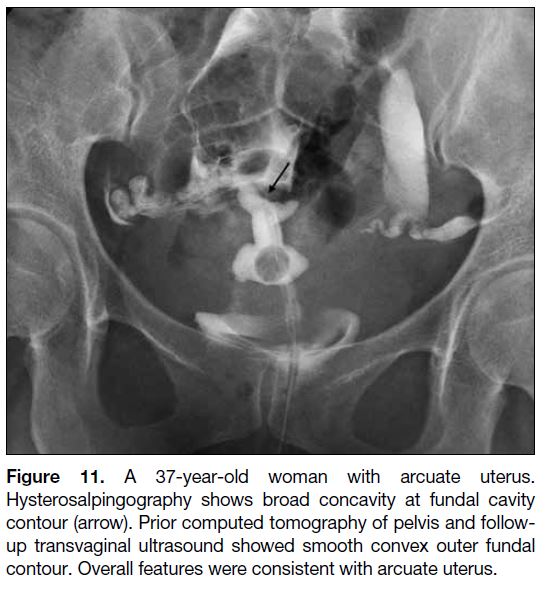

Arcuate uterus

Arcuate uterus is classified as class VI Müllerian duct

abnormality according to the American Fertility Society scheme.[15] Arcuate uterus arises from incomplete septal

resorption at the level of the uterine fundus resulting

in mild focal bulging. On HSG it manifests as broad

mild concavity of the fundal cavity contour (Figure 11). Further imaging with three-dimensional ultrasound or MRI to visualise the normal outer uterine contour is

helpful. It has been regarded as a normal uterine variant

without significant adverse impact on fertility.[15] [16]

Figure 11. A 37-year-old woman with arcuate uterus.

Hysterosalpingography shows broad concavity at fundal cavity

contour (arrow). Prior computed tomography of pelvis and follow-up

transvaginal ultrasound showed smooth convex outer fundal

contour. Overall features were consistent with arcuate uterus.

Congenital uterine anomalies

The wide spectrum and complex pathogenesis of

congenital uterine anomalies are beyond the scope

of this pictorial review. The developmental stages of the uterus include organogenesis of paired Müllerian

ducts, fusion, and septal resorption. Disorders in these

developmental stages result in congenital uterine

anomalies with varying severity and implications for

fertility.[10] HSG offers valuable information regarding

uterine cavity morphology and can suggest the presence

of a congenital uterine anomaly. Further evaluation with

three-dimensional pelvic ultrasound or MRI is warranted for assessment of outer or fundal uterine contour for

accurate diagnosis.

CONCLUSION

HSG is vital in reproductive medicine given its reliability in diagnosing tubal occlusion with relatively low

invasiveness. Systematic interpretation of HSG findings

and understanding of the spectrum of pathologies, including uterine contour changes, intracavity filling

defects, tubal patency, and tuboperitoneal pathology will

facilitate identification of the cause of female subfertility

and expedite management to improve reproductive

outcome.

REFERENCES

1. Dun EC, Nezhat CH. Tubal factor infertility: diagnosis and

management in the era of assisted reproductive technology. Obstet

Gynecol Clin North Am. 2012;39:551-66. Crossref

2. Omidiji OA, Toyobo OO, Adegbola O, Fatade A, Olowoyeye OA. Hysterosalpingographic findings in infertility—what has changed over the years? Afr Health Sci. 2019;19:1866-74. Crossref

3. Infertility workup for the women’s health specialist: ACOG Committee Opinion, Number 781. Obstet Gynaecol. 2019;133:e377-84. Crossref

4. Fertility problems: assessment and treatment. London: National

Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE); Sep 2017.

5. Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive

Medicine. Role of tubal surgery in the era of assisted reproductive

technology: a committee opinion. Fertil Steril. 2021;115:1143-50. Crossref

6. Simpson WL Jr, Beitia LG, Mester J. Hysterosalpingography: a reemerging study. Radiographics. 2006;26:419-31. Crossref

7. American College of Radiology. ACR Practice Parameter for the Performance of Hysterosalpingography. Available from: https://www.acr.org/-/media/ACR/Files/Practice-Parameters/HSG.pdf.

Accessed 1 Apr 2021.

8. Watson N. Reproductive system. In: Watson N, Jones H, editors.

Chapman & Nakielny’s Guide to Radiological Procedures. 6th ed.

Edinburgh, UK: Saunders; 2014. p 159-62.

9. Foroozanfard F, Sadat Z. Diagnostic value of hysterosalpingography

and laparoscopy for tubal patency in infertile women. Nurs Midwifery Stud. 2013;2:188-92. Crossref

10. Vickramarajah S, Stewart V, van Ree K, Hemingway AP, Crofton ME,

Bharwani N. Subfertility: what the radiologist needs to know.

Radiographics. 2017;37:1587-602. Crossref

11. Revzin MV, Mathur M, Dave HB, Macer ML, Spektor M. Pelvic

inflammatory disease: multimodality imaging approach with

clinical-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2016;36:1579-96. Crossref

12. Jenkins CS, Williams SR, Schmidt GE. Salpingitis isthmica nodosa:

a review of the literature, discussion of clinical significance, and

consideration of patient management. Fertil Steril. 1993;60:599-607. Crossref

13. Majmudar B, Henderson PH 3rd, Semple E. Salpingitis isthmica nodosa: a high-risk factor for tubal pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 1983;62:73-8.

14. Soares SR, Barbosa dos Reis MM, Camargos AF. Diagnostic

accuracy of sonohysterography, transvaginal sonography, and

hysterosalpingography in patients with uterine cavity diseases.

Fertil Steril. 2000;73:406-11. Crossref

15. The American Fertility Society classifications of adnexal adhesions,

distal tubal occlusion, tubal occlusion secondary to tubal ligation,

tubal pregnancies, Müllerian anomalies and intrauterine adhesions.

Fertil Steril. 1988;49:944-55. Crossref

16. Ubeda B, Paraira M, Alert E, Abuin RA. Hysterosalpingography:

spectrum of normal variants and nonpathologic findings. AJR Am

J Roentgenol. 2001;177:131-5. Crossref