Multidisciplinary Management of Ovarian, Fallopian Tube and Peritoneal Cancers with Emphasis on the Role of Cross-Sectional Imaging

PICTORIAL ESSAY

Hong Kong J Radiol 2023 Jun;26(2):142-52 | Epub 31 May 2023

Multidisciplinary Management of Ovarian, Fallopian Tube and Peritoneal Cancers with Emphasis on the Role of Cross-Sectional Imaging

OL Chan1, SC Young2, WWL Yip3, WH Chong1, KY Kwok1

1 Department of Radiology, Tuen Mun Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

2 Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Tuen Mun Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

3 Department of Clinical Oncology, Tuen Mun Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

Correspondence: Dr OL Chan, Department of Radiology, Tuen Mun Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China. Email: col950@ha.org.hk

Submitted: 23 Nov 2021; Accepted: 7 Apr 2022.

Contributors: All authors designed the study. OLC acquired and analysed the data, and drafted the manuscript. SCY, WWLY, WHC and KYK critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Funding/Support: This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data Availability: All data generated or analysed during the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: The study was approved by the New Territories West Cluster Research Ethics Committee of Hospital Authority, Hong Kong (Ref No.: NTWC/REC/21066). A waiver for written informed consent of patients was granted by the Committee as this manuscript is for pictorial review only and does not involve patient treatment/procedures.

INTRODUCTION

Ovarian cancer is the eighth most common cancer

among women worldwide and the second most common

gynaecological cancer mortality after cervical cancer.[1]

In Hong Kong, ovarian cancer ranks as the sixth most

common cancer in female and the most common cause of

gynaecological cancer mortality in 2020.[2] Approximately

two-thirds of patients with ovarian cancer are reported to

present with stage III-IV disease.[3] [4] High-grade serous

carcinoma accounts for about 70% of malignant ovarian

tumours.[5]

There is recent evidence that ovarian or peritoneal cancer may have a common origin from the fimbrial end of the

fallopian tubes. The ovarian cancer staging system was

updated in 2014 to include cancer of the fallopian tubes

and peritoneum.[3]

One of the most important prognostic factors in ovarian

cancer is the volume of residual disease after surgery. Cytoreductive surgery is the mainstay of treatment and

is considered optimal if there is no or ≤1 cm of gross

residual tumour and suboptimal if the residual tumour

is >1 cm.[6] [7]

In patients who present with advanced-stage disease,

preoperative imaging to assess the abdominopelvic

disease burden can help identify those at risk of having

>1 cm gross residual disease and help avoid futile

laparotomy. These patients may be first treated with

neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by reassessment

imaging and interval debulking surgery if optimal

tumour debulking is deemed possible.[3]

At our institution, management of patients with ovarian,

fallopian tube and peritoneal cancers is discussed by a

multidisciplinary team consisting of gynaecologists,

radiologists, and oncologists. A multidisciplinary

approach to cancer management has been shown to

improve a patient’s quality of life and prognosis.[8] [9]

This article describes the role of imaging in the

management of patients with ovarian cancer. The anatomy

of common sites of peritoneal lesions is reviewed and

features that may preclude optimal debulking surgery are

highlighted.

ROLE OF IMAGING

The role of imaging in the management of ovarian

cancer is to delineate the disease extent so that primary

treatment can be planned and indicate possible sites for

image-guided core biopsy for histological confirmation

when necessary.[4]

Previous studies compared the diagnostic accuracy of

different imaging modalities for detection of peritoneal

carcinomatosis in ovarian cancer. Computed tomography

(CT), magnetic resonance imaging, and positron

emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) all demonstrated >90% accuracy when compared

with diagnostic laparoscopy.[10] Magnetic resonance

imaging has the advantage of providing better soft tissue

differentiation but is less readily available and motion

artefacts may affect image quality. PET/CT is useful

for whole-body assessment but is likewise not readily

available. CT remains the most commonly performed

pretreatment imaging since it has high accuracy and

accessibility.

Compared with diagnostic laparoscopy, CT has a high

accuracy of >90% for detection of peritoneal deposits.

It is also more accurate in detecting peritoneal disease

in upper abdominal regions when compared with

laparoscopy. Limitations of CT are nonetheless its

reported decreased sensitivity of <80% in depicting

implants <1 cm in size, and inferior accuracy compared

with laparoscopy in detecting disease in pelvic and small

intestinal mesenteric regions.[11]

At our institution, CT of the abdomen and pelvis is

performed for pretreatment staging, with the lung bases

included in the scan range. The latter enables a search

for suspicious cardiophrenic lymph nodes and pleural

effusion that will require further investigations such as

pleural tapping to look for stage IV disease.[4] Looking

for stage IV disease is essential because this group of

patients may not be candidates for surgical debulking.

In patients with inoperable disease, interval debulking

is considered after two to three cycles of systemic

chemotherapy.[3] As well as monitoring cancer antigen 125 level, CT should be used to assess treatment response and

the feasibility of interval debulking surgery. PET/CT is

often supplementary when CT findings are inconclusive.[4]

Arrangement of timely follow-up imaging and planning

for interval debulking surgery following neoadjuvant

chemotherapy can be facilitated by a multidisciplinary

meeting.

PERITONEAL ANATOMY AND FLOW

OF PERITONEAL FLUID

Knowledge of the anatomy of the peritoneum and

flow of peritoneal fluid is important when assessing

peritoneal spread of disease. The internal surfaces

of the abdominopelvic cavity are lined with parietal

peritoneum. The visceral peritoneum lines the organs

that are intraperitoneal. The potential space between

these two layers of peritoneum is the peritoneal cavity

and generally contains a small amount of fluid to allow

frictionless movement of visceral organs within the

abdominal cavity. Ascites is often detected in a disease

state and may be due to increased capillary permeability

or obstructed lymphatics resulting in overall increased

peritoneal fluid.[12]

There are multiple peritoneal folds and reflections that

compartmentalise the abdominopelvic cavity. The

transverse mesocolon divides the peritoneal cavity into

the supracolic and infracolic spaces. The supracolic

space is separated by the falciform ligament into the left

and right. The right supracolic space contains the right

subphrenic space, subhepatic space, and the lesser sac.

The left supracolic space includes the perihepatic and

left subphrenic space. The infracolic space is further

divided by the small bowel mesentery into the larger left

and smaller right spaces. The small bowel mesentery

attaches from the ligament of Trietz at the left upper

quadrant to the ileocaecal junction at the right iliac fossa.

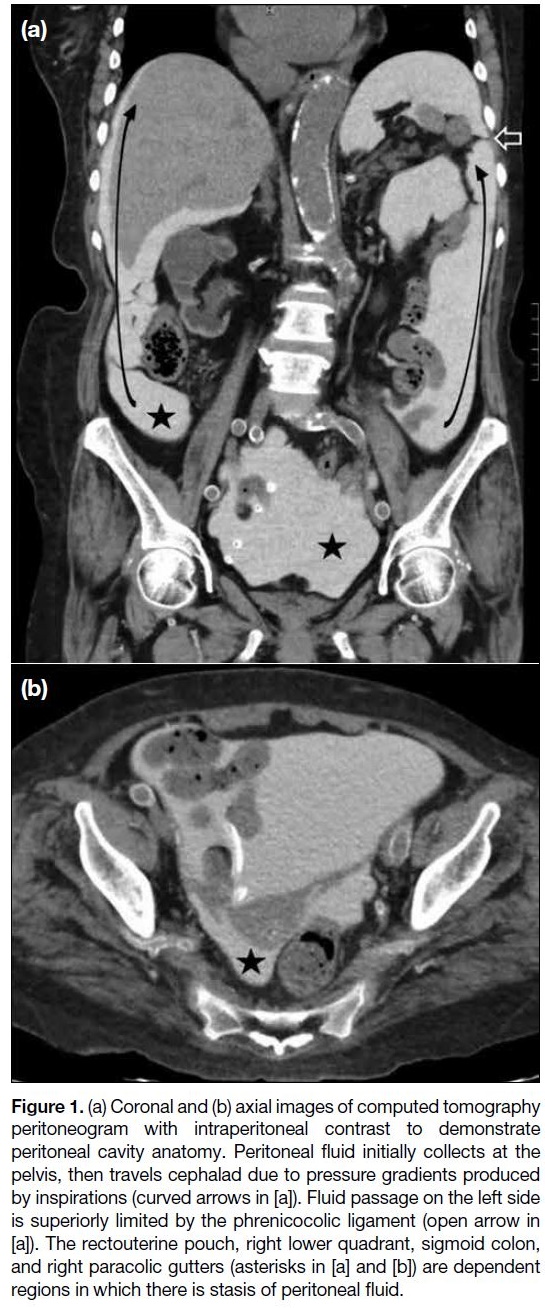

Initially, peritoneal fluid collects at a gravity-dependent site, the pouch of Douglas in woman and the rectovesical

space in men. It travels in a cephalad direction, entering

the paracolic gutters and then the supracolic spaces. On

the left side, fluid passage is superiorly limited by the

phrenicocolic ligament, hence more peritoneal fluid

flows into the right paracolic gutter (Figure 1). The

flow of peritoneal fluid is slow or arrested at dependent

regions due to gravity, and fluid stasis allows tumour

cells to be deposited. The four dependent areas include

the rectouterine pouch, right lower quadrant, sigmoid

colon, and right paracolic gutters.

Figure 1. (a) Coronal and (b) axial images of computed tomography

peritoneogram with intraperitoneal contrast to demonstrate

peritoneal cavity anatomy. Peritoneal fluid initially collects at the

pelvis, then travels cephalad due to pressure gradients produced

by inspirations (curved arrows in [a]). Fluid passage on the left side

is superiorly limited by the phrenicocolic ligament (open arrow in

[a]). The rectouterine pouch, right lower quadrant, sigmoid colon,

and right paracolic gutters (asterisks in [a] and [b]) are dependent

regions in which there is stasis of peritoneal fluid.

ASSESSMENT OF ABDOMINOPELVIC DISEASE BURDEN

The most frequent routes for dissemination of ovarian

cancer are by direct pelvic invasion and via transcoelomic peritoneal spread.[13] Less frequently, it may also

spread along the lymphatics via the utero-ovarian,

infundibulopelvic and round ligament pathways.[3] The

most common lymphatic spread is along the utero-ovarian

pathway to the para-aortic and paracaval nodes

at the level of the kidney.[7] Haematogenous spread is rare

and seldom present at initial diagnosis.

Primary Tumour

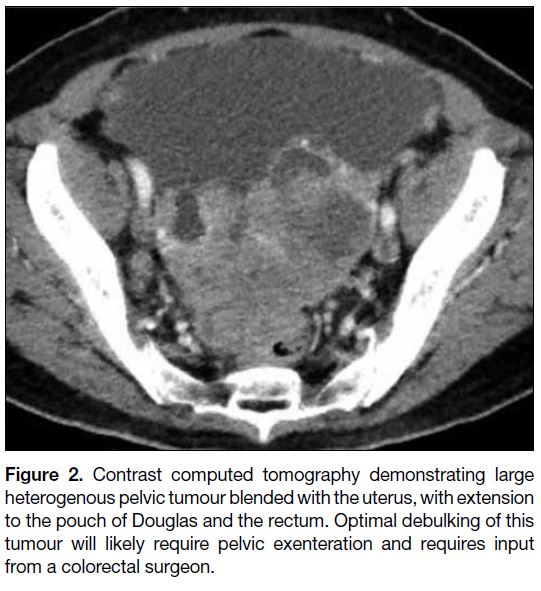

The size and location of the primary ovarian tumour

should be described. Pelvic sidewall invasion is suspected

when the distance between the tumour and the muscular

pelvic sidewall is <3 mm, or when there is encasement

of >90% of the circumference of iliac vessels.[13] Any

invasion to the adjacent organs such as the urinary

bladder or rectum should be noted since it may require

additional surgical input from other subspecialties to

achieve optimal debulking (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Contrast computed tomography demonstrating large

heterogenous pelvic tumour blended with the uterus, with extension

to the pouch of Douglas and the rectum. Optimal debulking of this

tumour will likely require pelvic exenteration and requires input

from a colorectal surgeon.

Peritoneal Carcinomatosis

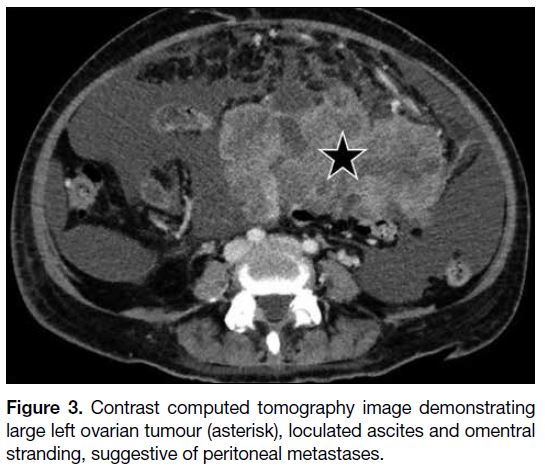

Assessment of peritoneal carcinomatosis is crucial

since it affects staging and subsequent management.

The presence of ascites raises a suspicion of peritoneal

involvement and loculated ascites usually indicates

peritoneal metastasis. Signs of early peritoneal disease

are subtle and can be easily missed. Multiplanar

reformatted CT images are helpful in the assessment

of peritoneal lesions. Coronal and sagittal reformatted images improve detection of lesions on curved surfaces

such as the diaphragm, paracolic gutters, and pelvis

(Figure 3).[7]

Figure 3. Contrast computed tomography image demonstrating

large left ovarian tumour (asterisk), loculated ascites and omentral

stranding, suggestive of peritoneal metastases.

The operability of peritoneal lesions is related to

multiple factors such as the location of peritoneal

deposits, their morphology and multiplicity, and their

size and relationship with adjacent organs. Peritoneal

carcinomatosis can present with a wide range of

morphological appearance on CT. Subtle soft tissue

infiltration, mild thickening or nodularity of the

peritoneum may be the only findings in early peritoneal

disease. Soft tissue peritoneal implants are usually

observed in advanced peritoneal disease. These can

present as solitary or multiple nodules, or coalesce to

form plaque-like lesions and larger masses. They may

show contrast enhancement; metastases from serous

cystadenocarcinoma may be calcified.[12]

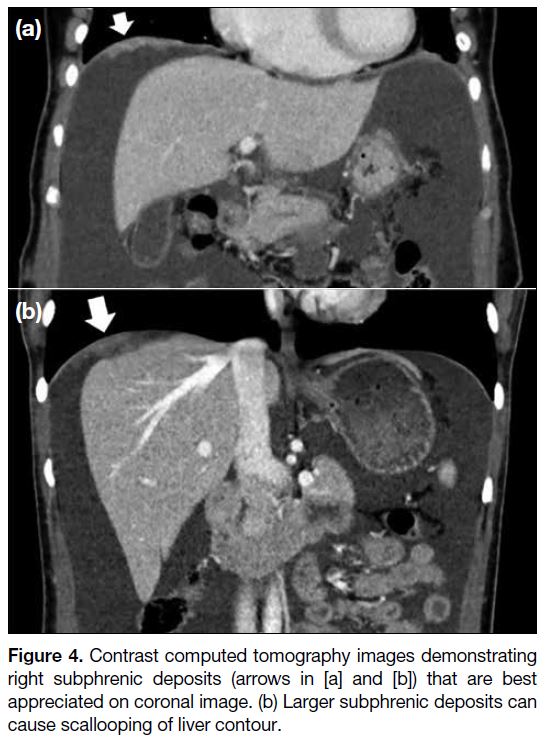

Upper Abdomen

The right subphrenic region is frequently involved since

there is preferential flow of peritoneal fluid along the

right side of the abdomen. Coronal and sagittal images

enable better assessment of peritoneal deposits at the

hemidiaphragm. Nodular- or plaque-like thickening may

be observed. Larger deposits at the subphrenic region

may cause scalloping of the liver or splenic contour. On

post-contrast phase, these implants are hypoenhancing

relative to the liver or splenic parenchyma (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Contrast computed tomography images demonstrating right subphrenic deposits (arrows in [a] and [b]) that are best appreciated on coronal image. (b) Larger subphrenic deposits can cause scallooping of liver contour.

In the upper abdomen, it is also essential to look for any involvement of the peritoneal ligaments, including the

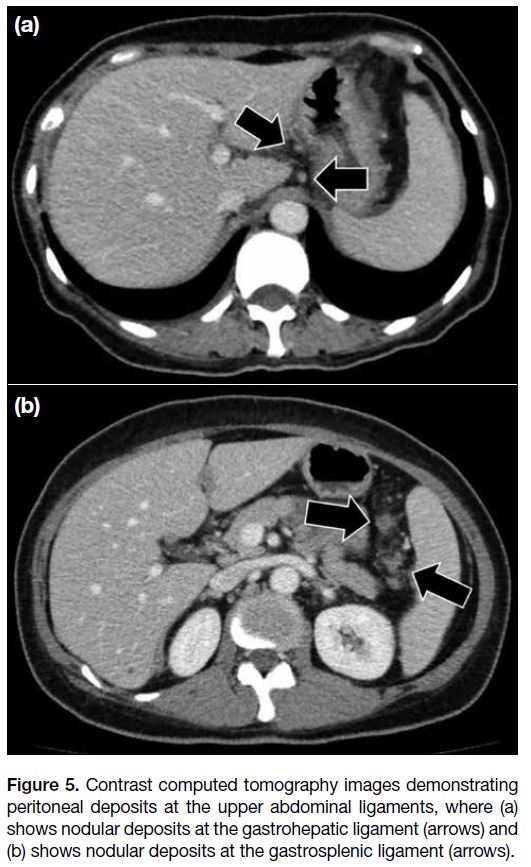

gastrohepatic and gastrosplenic ligaments (Figure 5).

Increased soft tissue stranding, thickening or nodular

deposits at these ligaments usually suggest involvement.

Figure 5. Contrast computed tomography images demonstrating

peritoneal deposits at the upper abdominal ligaments, where (a)

shows nodular deposits at the gastrohepatic ligament (arrows) and

(b) shows nodular deposits at the gastrosplenic ligament (arrows).

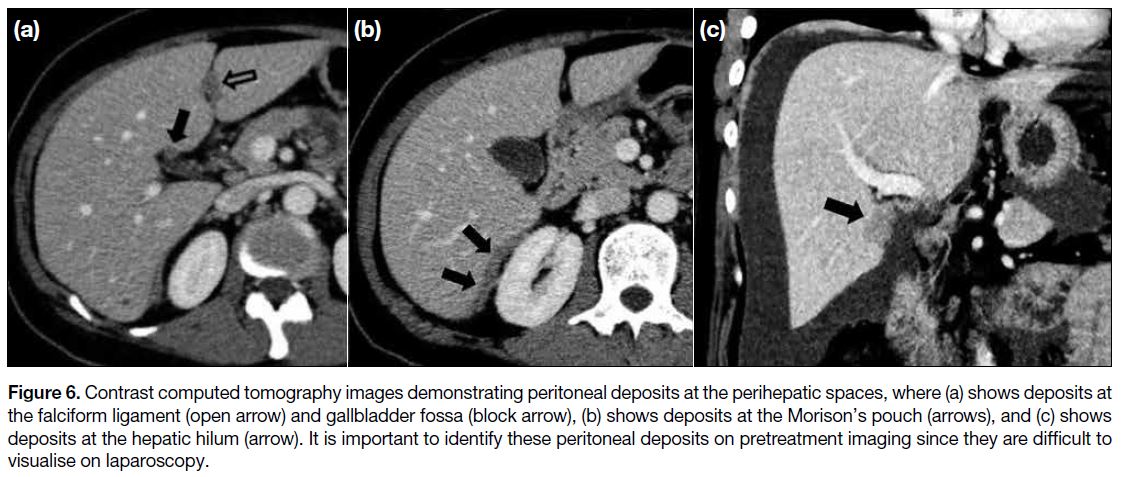

Any tumour deposits at the perihepatic spaces should be

specified, including the fissure for falciform ligament,

gallbladder fossa, porta hepatism, and lesser sac (Figure 6). Peritoneal lesions at these sites, particularly when

>2 cm in size, are probably non-resectable.[14] Any

subcapsular implants at the Morison’s pouch extending

to the inferior vena cava must be described because they

pose a surgical challenge due to increased bleeding risk.[7]

Figure 6. Contrast computed tomography images demonstrating peritoneal deposits at the perihepatic spaces, where (a) shows deposits at

the falciform ligament (open arrow) and gallbladder fossa (block arrow), (b) shows deposits at the Morison’s pouch (arrows), and (c) shows

deposits at the hepatic hilum (arrow). It is important to identify these peritoneal deposits on pretreatment imaging since they are difficult to

visualise on laparoscopy.

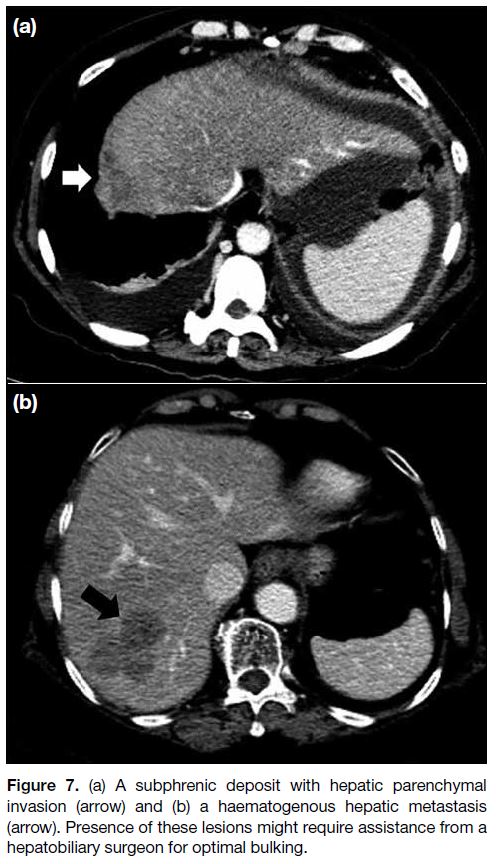

Since haematogenous metastases are extremely rare at

presentation, apparent parenchymal involvement of the

liver and spleen are more commonly caused by invasive

serosal surface implants rather than haematogenous

metastases (Figure 7). Differentiation of a surface lesion

versus parenchymal invasion lesion is particularly

important for the liver because partial hepatectomy may be required in the latter with assistance of a hepatobiliary

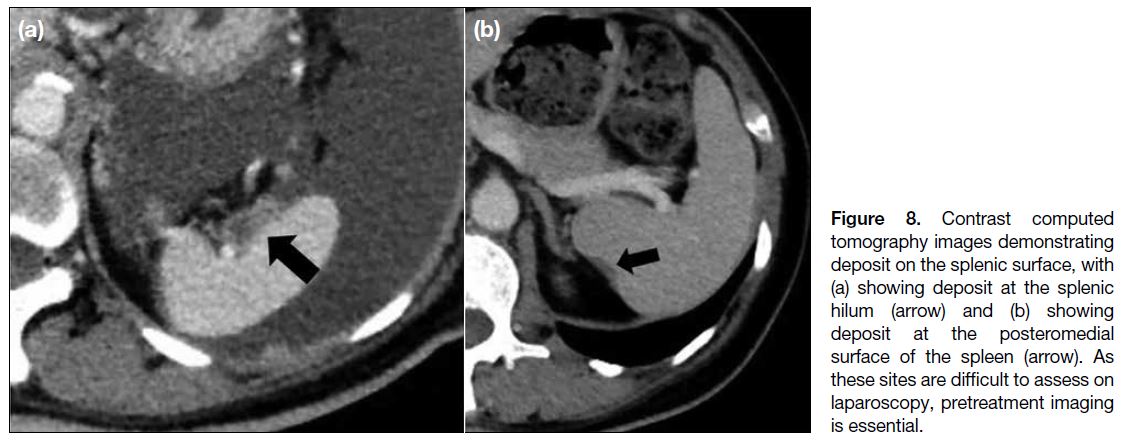

surgeon. Distinguishing between a surface lesion

and invasive parenchymal lesion at the spleen is less

important because splenectomy is more easily performed

(Figure 8).[13]

Figure 7. (a) A subphrenic deposit with hepatic parenchymal

invasion (arrow) and (b) a haematogenous hepatic metastasis

(arrow). Presence of these lesions might require assistance from a

hepatobiliary surgeon for optimal bulking.

Figure 8. Contrast computed

tomography images demonstrating deposit on the splenic surface, with (a) showing deposit at the splenic hilum (arrow) and (b) showing deposit at the posteromedial surface of the spleen (arrow). As these sites are difficult to assess on laparoscopy, pretreatment imaging is essential.

Paracolic Gutters, Omentum, and Mesentery

The bilateral paracolic gutters are also common sites of

peritoneal deposits because of peritoneal fluid stasis. It

is helpful to assess with both axial and coronal images.

Tumour deposits present as irregular thickening and

nodularity (Figure 9).

Figure 9. (a) Axial

and (b) coronal images from contrast computed tomography demonstrating deposits at the paracolic gutters (arrows).

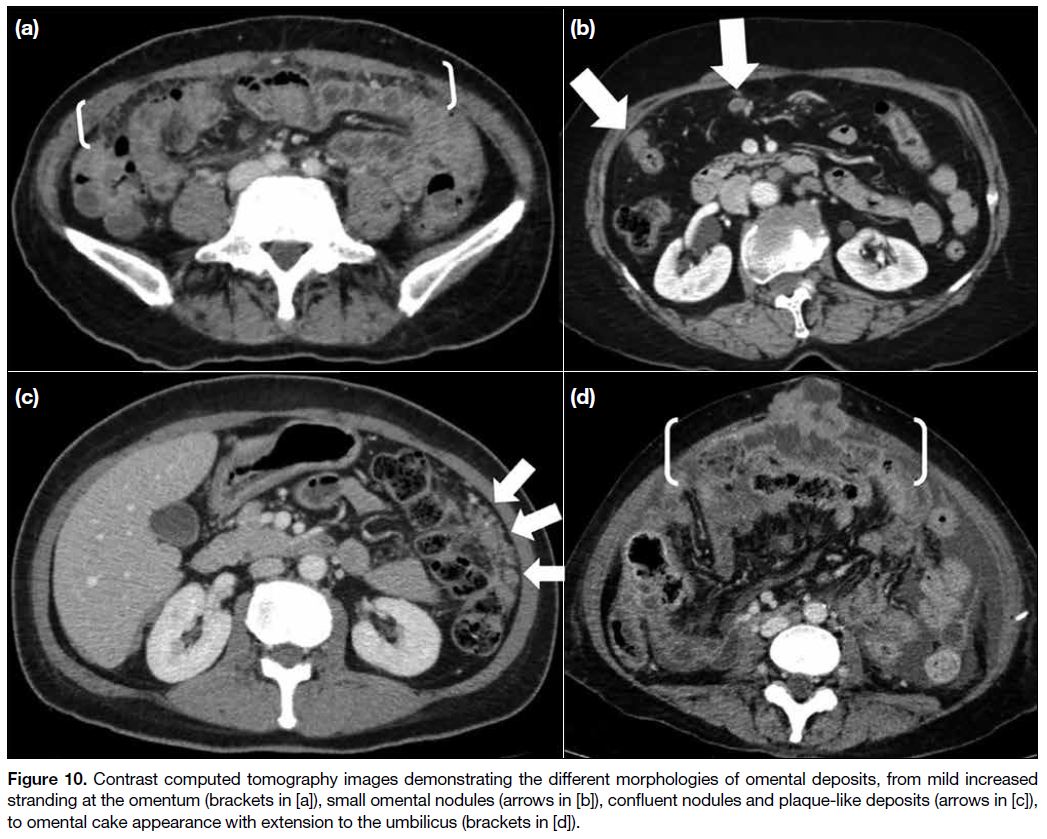

Infiltration of the omental fat can present as increased

soft tissue stranding and omental nodules of various

sizes. When these small nodules coalesce, they give

rise to larger omental plaques or mass-like lesions that

are commonly referred to as omental cakes. Greater

omental involvement usually does not preclude surgery

since omentectomy is routinely performed in debulking

surgery. Nonetheless extension of omental metastases to

the anterior abdominal wall or umbilicus may preclude

surgery (Figure 10).[4] [12]

Figure 10. Contrast computed tomography images demonstrating the different morphologies of omental deposits, from mild increased

stranding at the omentum (brackets in [a]), small omental nodules (arrows in [b]), confluent nodules and plaque-like deposits (arrows in [c]),

to omental cake appearance with extension to the umbilicus (brackets in [d]).

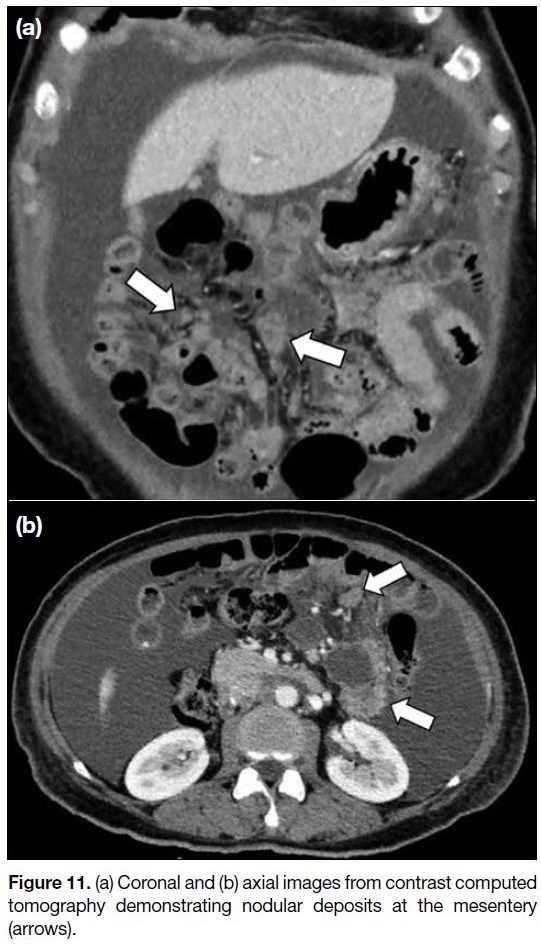

Infiltration of the mesentery can present as misty

mesentery or clustered soft-tissue nodules (Figure 11).

Peritoneal deposits at the mesentery can cause tethering

of the bowel loops and intestinal obstruction. Intestinal

obstruction is a common morbidity associated with

metastatic ovarian cancer, reported to occur in about 50% of cases.[12] Detection of segmental small bowel

obstruction and extensive tumour deposits on the small

bowel surface or at the mesenteric root is important

because these features may preclude surgery.[14] Serosal

implants at the bowel loops are difficult to detect,

particularly in the absence of complications such as

intestinal obstruction. Involvement of the small bowel

may present as segmental mural thickening and softtissue

mass involving the serosa and adjacent mesentery.

Depending on the extent of involvement, these bowel

serosal implants may be resected with the assistance of a

gastrointestinal surgeon.

Figure 11. (a) Coronal and (b) axial images from contrast computed tomography demonstrating nodular deposits at the mesentery (arrows).

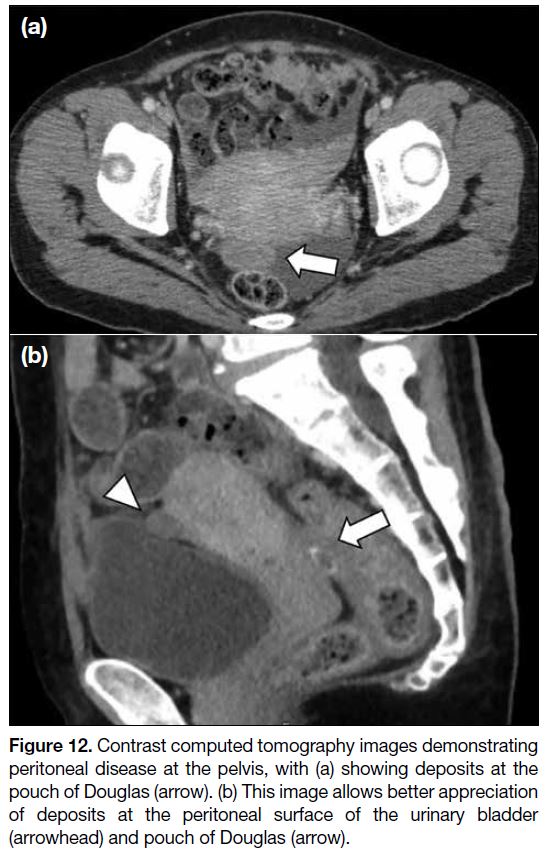

In the pelvis, common sites of deposits include the

surface of the urinary bladder, sigmoid mesocolon,

pelvic sidewall, pouch of Douglas, and surface of the

sigmoid and rectum. Lesions at the bilateral uterosacral

ligament and pelvic sidewall are better seen on axial and

coronal images. Lesions at the peritoneal surface of the

bladder, pouch of Douglas, and rectosigmoid regions are

better observed on sagittal images. Again, these deposits

can present as soft tissue thickening or a mass (Figure 12).

Figure 12. Contrast computed tomography images demonstrating peritoneal disease at the pelvis, with (a) showing deposits at the pouch of Douglas (arrow). (b) This image allows better appreciation of deposits at the peritoneal surface of the urinary bladder (arrowhead) and pouch of Douglas (arrow).

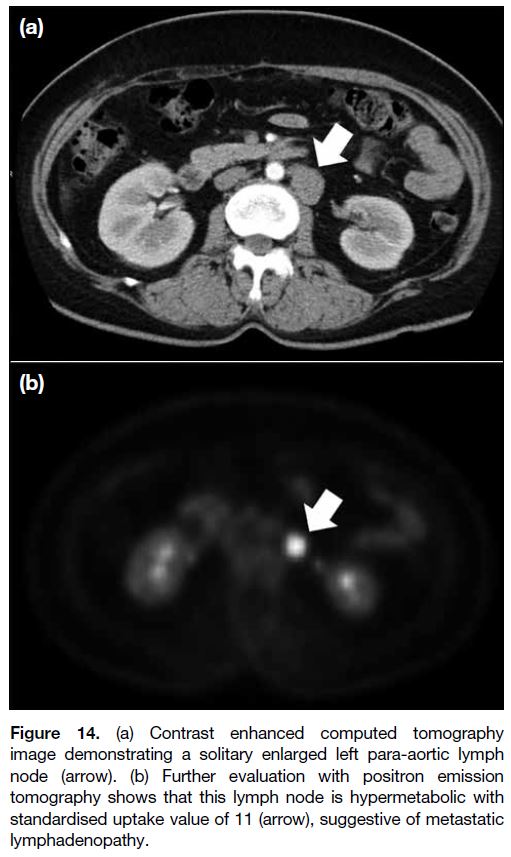

Lymphadenopathy

Lymphatic spread commonly involves the para-aortic

lymph nodes. An enlarged node with >1 cm short

axis suggests malignant lymphadenopathy.[13] Apart

from increased nodal size, necrosis or clustering of

lymph nodes are also suspicious features of metastatic

involvement. Any enlarged lymph node at the suprarenal para-aortic, portacaval, porta hepatis or celiac axis

should be specified because these sites may preclude

surgery (Figures 13 and 14).

Figure 13. Malignant para-aortic lymphadenopathy above the level

of the renal vein (circle in [a]) and enlarged paracaval lymph node

(arrow in [b]). These are considered surgically difficult sites.

Figure 14. (a) Contrast enhanced computed tomography

image demonstrating a solitary enlarged left para-aortic lymph

node (arrow). (b) Further evaluation with positron emission

tomography shows that this lymph node is hypermetabolic with

standardised uptake value of 11 (arrow), suggestive of metastatic

lymphadenopathy.

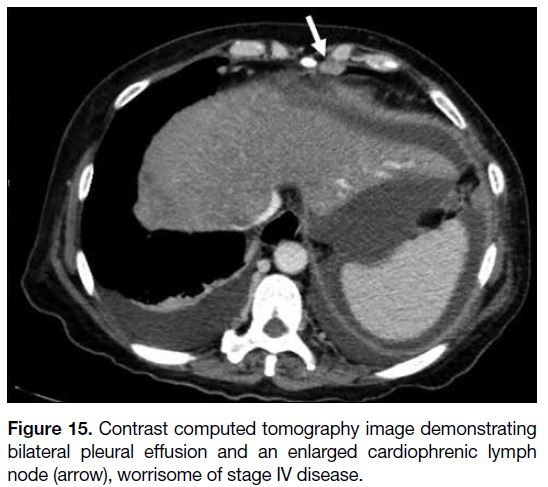

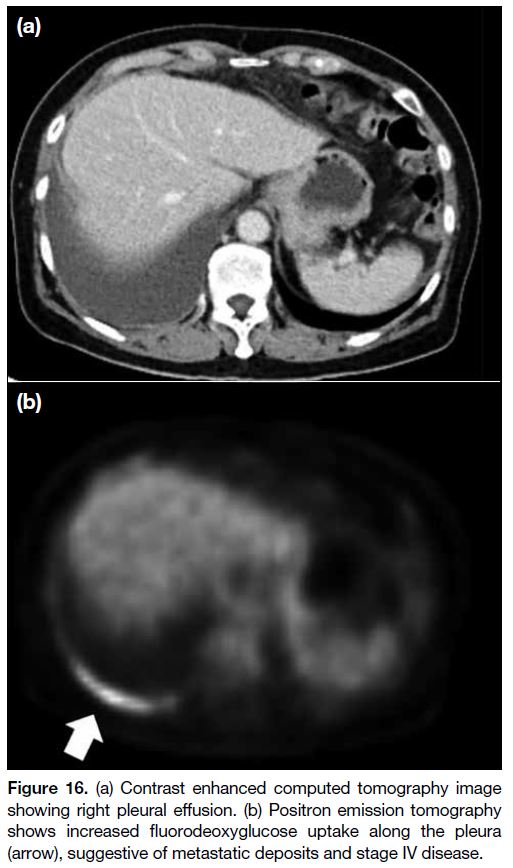

Lung Base

Assessment of the lung bases on preoperative CT is

crucial since these extraperitoneal sites are not accessible

by laparoscopy. The cardiophrenic lymph node is

considered enlarged when the short axis is >5 mm[7] [15] and

may suggest stage IV disease. This precludes surgery.

Any pleural effusion should be further investigated

to look for stage IV disease that is deemed inoperable

(Figures 15 and 16).

Figure 15. Contrast computed tomography image demonstrating

bilateral pleural effusion and an enlarged cardiophrenic lymph

node (arrow), worrisome of stage IV disease.

Figure 16. (a) Contrast enhanced computed tomography image

showing right pleural effusion. (b) Positron emission tomography

shows increased fluorodeoxyglucose uptake along the pleura

(arrow), suggestive of metastatic deposits and stage IV disease.

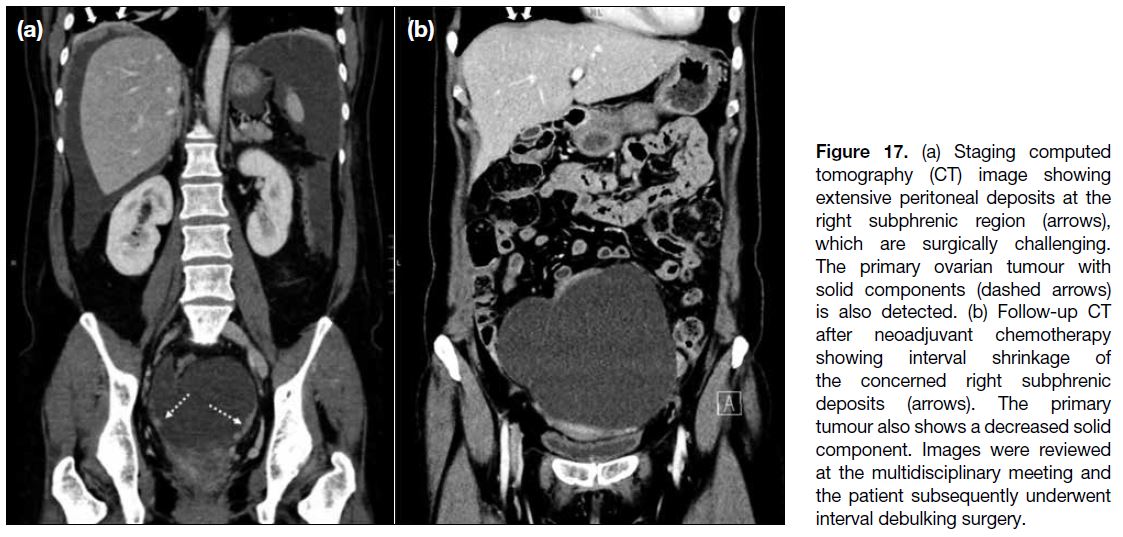

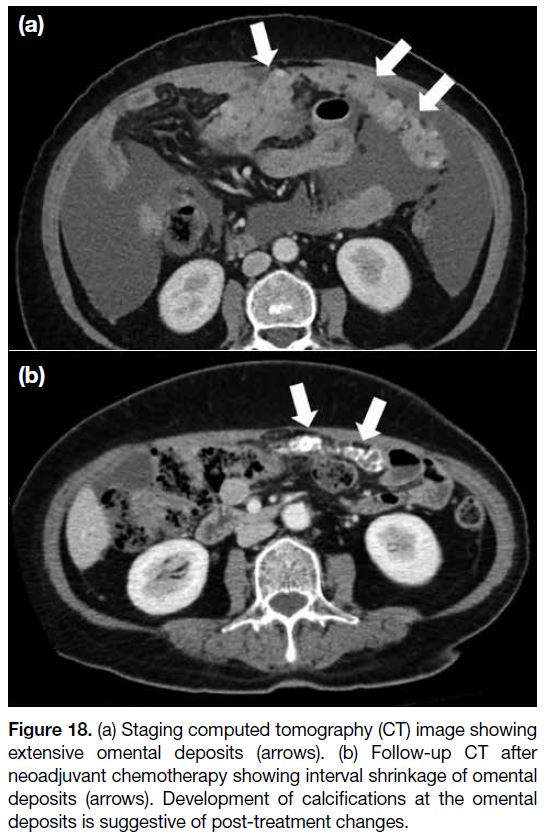

Assessment for Interval Debulking Surgery

At our institution, follow-up imaging is performed after

three cycles of neoadjuvant chemotherapy in patients with inoperable disease. Images are reviewed at the

multidisciplinary meeting for consideration of interval

debulking surgery (Figures 17 and 18).

Figure 17. (a) Staging computed tomography (CT) image showing extensive peritoneal deposits at the right subphrenic region (arrows), which are surgically challenging. The primary ovarian tumour with solid components (dashed arrows) is also detected. (b) Follow-up CT after neoadjuvant chemotherapy showing interval shrinkage of the concerned right subphrenic deposits (arrows). The primary tumour also shows a decreased solid component. Images were reviewed at the multidisciplinary meeting and the patient subsequently underwent interval debulking surgery.

Figure 18. (a) Staging computed tomography (CT) image showing

extensive omental deposits (arrows). (b) Follow-up CT after

neoadjuvant chemotherapy showing interval shrinkage of omental

deposits (arrows). Development of calcifications at the omental

deposits is suggestive of post-treatment changes.

Cancer of the ovaries, fallopian tubes and peritoneum

share similar morphological and clinical features. In

patients with advanced disease, a tubal or ovarian origin

can be difficult to delineate because tumour growth may

obscure the primary site.[6] Preoperative assessment for

these patients should be similar.

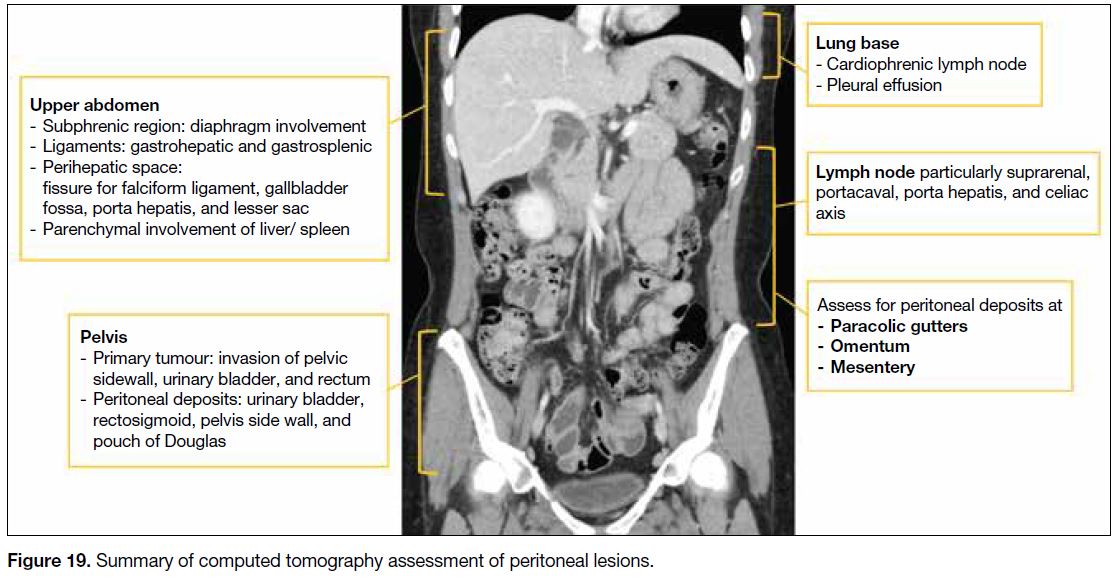

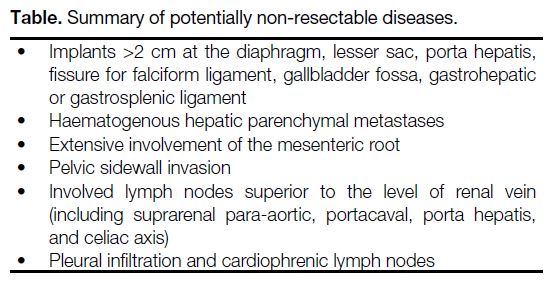

Figure 19 summarises CT assessment of peritoneal

lesions and the Table lists potentially non-resectable disease.

Figure 19. Summary of computed tomography assessment of peritoneal lesions.

Table. Summary of potentially non-resectable diseases.

CONCLUSION

Pretreatment imaging is helpful to evaluate abdominopelvic disease burden in patients with ovarian,

fallopian tube and peritoneal cancers, and to identify

patients at risk of having suboptimal debulking surgery

in whom laparotomy would be futile. It has been shown

that CT has high accuracy in detecting peritoneal lesions.

Assessment of peritoneal involvement can be improved

by understanding the peritoneal anatomy, route of tumour

dissemination, as well as common sites of peritoneal

deposits. The role of radiologists in the multidisciplinary

team is to alert clinicians to the presence of lesions that

may complicate surgery or preclude optimal debulking.

Patient-centred management should be discussed

at the multidisciplinary meeting to decide which of

cytoreductive surgery or neoadjuvant chemotherapy is

most appropriate.

REFERENCES

1. Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I,

Jemal A, et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN

estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in

185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71:209-49. Crossref

2. Hong Kong Cancer Registry. Overview of Hong Kong Cancer

Statistics of 2020. Hong Kong Hospital Authority; Oct 2021.

Available from: https://www3.ha.org.hk/cancereg/pdf/overview/Overview%20of%20HK%20Cancer%20Stat%202020.pdf.

Assessed 26 Apr 2023.

3. Berek J, Kehoe ST, Kumar L, Friedlander M. Cancer of the ovary, fallopian tube, and peritoneum. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2018;143 Suppl 2:59-78. Crossref

4. Forstner R, Sala E, Kinkel K, Spencer J; European Society of Urogenital Radiology. ESUR guidelines: ovarian cancer staging and follow-up. Eur Radiol. 2010;20:2773-80. Crossref

5. Saida T, Tanaka YO, Matsumoto K, Satoh T, Yoshikawa H, Minami M. Revised FIGO staging system for cancer of the

ovary, fallopian tube, and peritoneum: important implications for radiologists. Jpn J Radiol. 2015;34:117-24. Crossref

6. Javadi S, Ganeshan DM, Qayyum A, Iyer RB, Bhosale P. Ovarian

cancer, the revised FIGO staging system, and the role of imaging.

AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2016;206:1351-60. Crossref

7. Nougaret S, Addley HC, Colombo PE, Fujii S, Al Sharif SS, Tirumani SH, et al. Ovarian carcinomatosis: how the radiologist can help plan the surgical approach. Radiographics. 2012;32:1775-800. Crossref

8. Falzone L, Scandurra G, Lombardo V, Gattuso G, Lavoro A, Distefano AB, et al. A multidisciplinary approach remains the best strategy to improve and strengthen the management of ovarian cancer (Review). Int J Oncol. 2021;59:53. Crossref

9. Spencer JA. A multidisciplinary approach to ovarian cancer at diagnosis. Br J Radiol. 2005;78 Spec No 2:S94-102. Crossref

10. Schmidt S, Meuli RA, Achtari C, Prior JO. Peritoneal carcinomatosis in primary ovarian cancer staging: comparison between MDCT, MRI, and 18F-FDG PET/CT. Clin Nucl Med. 2015;40:371-7. Crossref

11. Ahmed SA, Abou-Taleb H, Yehia A, El Malek NA, Siefeldein GS, Badary DM, et al. The accuracy of multi-detector computed tomography and laparoscopy in the prediction of peritoneal

carcinomatosis index score in primary ovarian cancer. Acad Radiol.

2019;26:1650-8. Crossref

12. Pannu HK, Bristow RE, Montz FJ, Fishman EK. Multidetector CT of peritoneal carcinomatosis from ovarian cancer. Radiographics. 2003;23:687-701. Crossref

13. Sahdev A. CT in ovarian cancer staging: how to review and report with emphasis on abdominal and pelvic disease for surgical planning. Cancer Imaging. 2016;16:19. Crossref

14. Sugarbaker PH. Surgical responsibilities in the management of

peritoneal carcinomatosis. J Surg Oncol. 2010;101:713-24. Crossref

15. Kolev V, Mironov S, Mironov O, Ishill N, Moskowitz CS, Gardner GJ, et al. Prognostic significance of supradiaphragmatic lymphadenopathy identified on preoperative computed tomography

scan in patients undergoing primary cytoreduction for advanced

epithelial ovarian cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2010;20:979-84. Crossref