Successful Endovascular Management of Iatrogenic Aortic Coarctation Following Total Aortic Arch Repair in Type B Dissection: a Case Report

CASE PEPORT

Hong Kong J Radiol 2023 Jun;26(2):138-41 | Epub 15 May 2023

Successful Endovascular Management of Iatrogenic Aortic Coarctation Following Total Aortic Arch Repair in Type B

Dissection: a Case Report

PP Ng1, SCW Cheung2, CKL Ho3, KKY Man2, KKH Choi2

1 Department of Radiology and Imaging, Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

2 Department of Radiology, Queen Mary Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

3 Department of Cardiothoracic Surgery, Queen Mary Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

Correspondence: Dr PP Ng, Department of Radiology and Imaging, Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China. Email: npp782@ha.org.hk

Submitted: 6 Oct 2021; Accepted: 26 Jan 2022.

Contributors: All authors designed the study. PPN and KKHC acquired the data. All authors analysed the data. PPN, SCWC, CKLH and KKHC drafted the manuscript. All authors critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding/Support: This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data Availability: All data generated or analysed during the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: The patients were treated in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and provided written informed consent for all treatments and procedures and consent for publication.

INTRODUCTION

Frozen elephant trunk (FET) technique has been

commonly used in the management of a wide variety

of thoracic aortic pathology. Postoperative kinking

of an FET stent graft resulting in clinically significant

aortic coarctation is rare. We report a challenging case

of a patient with chronic type B aortic dissection who

underwent FET repair that was complicated by clinically

significant FET graft kinking but successfully treated

with endovascular stenting.

CASE REPORT

A 47-year-old man with a history of chronic type B

aortic dissection had a dissection flap starting just distal

to the origin of the aberrant right subclavian artery

(SCA) and extending down to the aortic bifurcation.

Sequential computed tomography angiography (CTA)

showed progressive dilatation of an aortic arch dissecting

aneurysm (5.8 cm) and narrowing of the true lumen. In

May 2021, he underwent ascending and total aortic arch

replacement with FET graft (Thoraflex Hybrid; Terumo

Aortic, Renfrewshire, United Kingdom), aorto-right axillary artery bypass and embolisation of the aberrant right SCA with Amplatz vascular plug (Abbott Medical, Plymouth [MN], US).

Following the surgery, he developed persistent

hypertension despite multiple antihypertensive

medications and progressive respiratory distress. There

was significant upper and lower limb blood pressure

(BP) discrepancy up to 40 mmHg. Echocardiogram

demonstrated preserved left ventricular ejection fraction

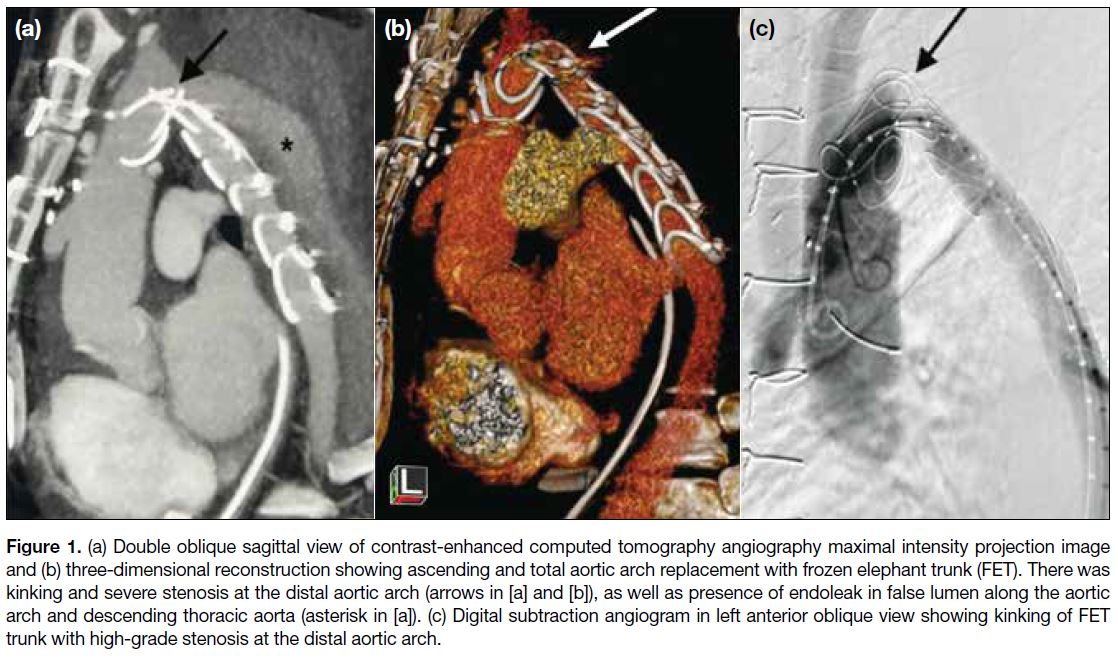

(60%). CTA on postoperative day 5 revealed kinking of

the FET stent graft at the distal aortic arch with marked

luminal stenosis (Figure 1a and b). Another finding was

an endoleak from the aberrant right SCA, later managed

by surgical ligation of the right SCA origin. Aortic

angiogram confirmed high-grade stenosis of the FET

graft at the distal aortic arch (Figure 1c). Intra-arterial

BP measurement revealed a 53-mmHg pressure gradient

across the stenosis.

Figure 1. (a) Double oblique sagittal view of contrast-enhanced computed tomography angiography maximal intensity projection image

and (b) three-dimensional reconstruction showing ascending and total aortic arch replacement with frozen elephant trunk (FET). There was

kinking and severe stenosis at the distal aortic arch (arrows in [a] and [b]), as well as presence of endoleak in false lumen along the aortic

arch and descending thoracic aorta (asterisk in [a]). (c) Digital subtraction angiogram in left anterior oblique view showing kinking of FET

trunk with high-grade stenosis at the distal aortic arch.

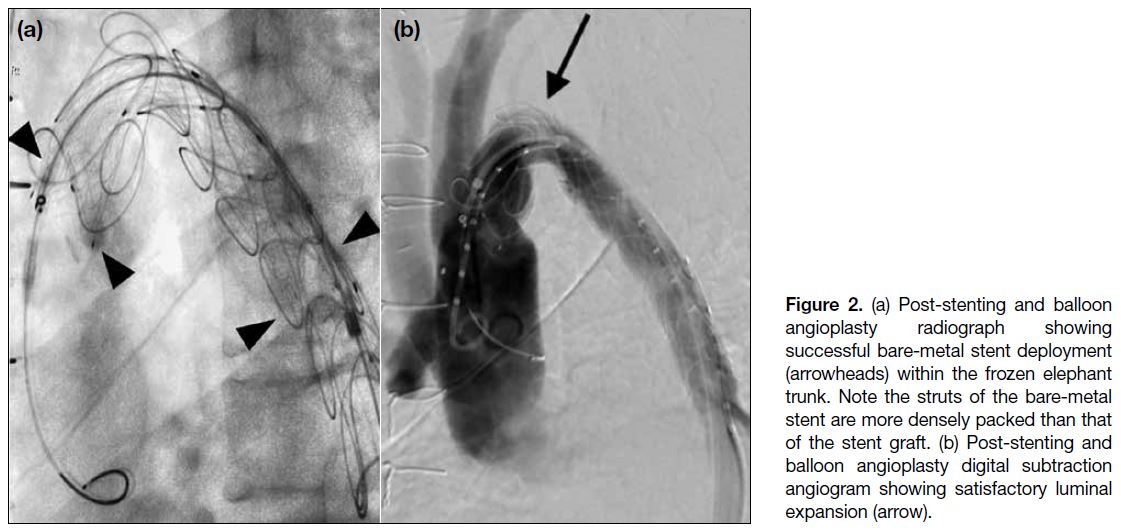

Endovascular stenting of the iatrogenic aortic coarctation was performed with a bare-metal stent (BMS) [Sinus-XL 34 × 100 mm; OptiMed, Ettlingen, Germany]

under local anaesthesia. Due to the acute angulation at the

aortic arch and tight stenosis, an attempt to deploy across

the stenosis within the FET was particularly challenging.

Difficulties were encountered during passage of the

delivery system across the stenosis as well as retraction

of the outer sheath for stent deployment. To overcome

these difficulties, balloon dilatation of the stenosis was

first performed. This was followed by partial deployment

of two-thirds of the stent within a 12-F sheath (Cook

Medical, Bloomington [IN], US) with the sheath tip

rested at the non-kinked portion of the FET. The entire

complex was then advanced proximally to the desirable

zone. The partially opened stent was deployed across the

stenosis by unsheathing the 12-F sheath with constant

forward pressure on the delivery system to avoid distal

migration. Post-stenting dilatation with a 32-mm Coda

balloon catheter (Cook Medical, Bloomington [IN], US)

achieved satisfactory luminal expansion (Figure 2). Post-stenting

BP gradient improved to 20 mmHg.

Figure 2. (a) Post-stenting and balloon angioplasty radiograph showing successful bare-metal stent deployment (arrowheads) within the frozen elephant trunk. Note the struts of the bare-metal stent are more densely packed than that of the stent graft. (b) Post-stenting and balloon angioplasty digital subtraction angiogram showing satisfactory luminal expansion (arrow).

On day 3 post-stenting, the patient developed haemolytic

anaemia and syncope. Urgent CTA revealed no source

of bleeding. The BMS across the coarctation was

partially collapsed but there was interval luminal gain

when compared with preprocedural CTA (Figure 3). The haemolytic anaemia was suspected to be stent-related;

a repeat aortic angiogram was performed on

postoperative day 14 and demonstrated a small residual

pressure gradient (8 mmHg) across the kinking. Since

the stent remained partially collapsed, repeat balloon

angioplasty was performed with 32-mm Coda balloon

(Cook Medical, Bloomington [IN], US) and 26-mm

Atlas balloon (Bard Medical, New Providence [NJ],

US). Despite the lack of significant stent expansion

on fluoroscopy, the pressure gradient disappeared by

the end of procedure. The patient made an uneventful

recovery and was subsequently discharged.

Figure 3. Double oblique sagittal contrast-enhanced computed tomography angiography image showing partial collapse of the bare-metal stent (white arrow) within the frozen elephant trunk (black arrow) at the site of kinking. Note the interval expansion of aortic lumen.

Follow-up CTA performed 1 month post-stenting

revealed no interval collapse of the stent or luminal re-stenosis.

The patient was asymptomatic with no upper

and lower limb BP discrepancy or haemoglobin drop.

DISCUSSION

Although the FET technique is now widely used

to manage thoracic aortic dissection, postoperative

kinking of the stent graft that necessitates secondary

intervention has rarely been reported in the literature.

FET kinking often occurs at the junction of the distal

aortic arch and descending aorta.[1] Risk factors for graft

kinking include acute aortic arch angulation, marked true lumen narrowing, a rigid chronic dissection membrane,

reperfusion of false lumen, use of a low radial force

device or presence of a non-stent part in the FET graft.[2] [3] [4]

Although rare, kinking can result in coarctation, graft

thrombosis, haemolytic anaemia, and heart failure.

Secondary surgery to rectify the kinked graft can be

complex and necessitate cardiopulmonary bypass.

Endovascular repair offers a minimally invasive option

that can be performed under local anaesthesia. Realigning

a stent within the kinked graft may provide adequate

scaffolding to maintain graft patency. Complications

include stent fracture, migration, and collapse.

Graft kinking in this patient was both clinically and

radiologically significant, as evidenced by the presence

of heart failure, haemolytic anaemia, marked luminal

narrowing on imaging, and significant pressure gradient.

Possible contributing factors in this case included acute

aortic arch angulation, rigid chronic dissection flap, and

stenotic true lumen. As angioplasty alone would not

have provided adequate scaffolding, alignment of the

FET with stent was chosen.

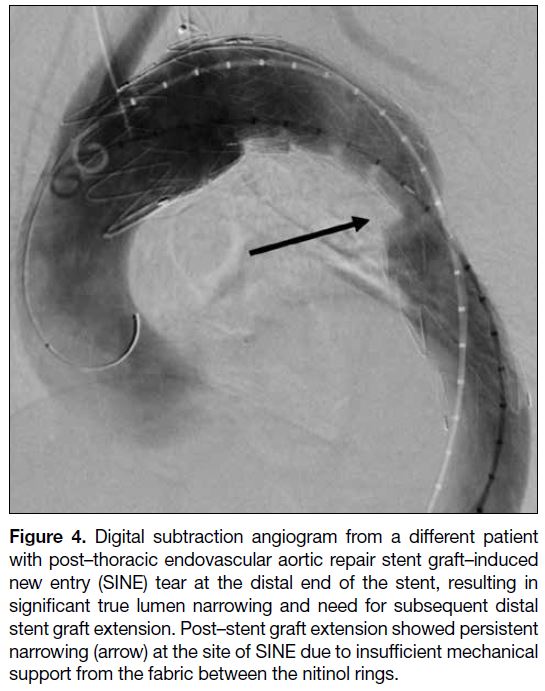

An ideal stent in this scenario would have high radial

force without compromised flexibility. Stent grafts are

often preferred since they are available in a wide range

of sizes, up to 46 mm in diameter, and with tapering

property; they also provide additional safety in case of inadvertent aortic rupture during the procedure. In our

experience, better support can be achieved by positioning

the stent struts at the most stenotic point to maximise

mechanical support (Figure 4). This is more achievable

with BMS because their stent struts are more densely

packed compared with stent grafts where the nitinol

rings are typically separated by 10 to 15 mm of fabric.

Figure 4. Digital subtraction angiogram from a different patient

with post–thoracic endovascular aortic repair stent graft–induced

new entry (SINE) tear at the distal end of the stent, resulting in

significant true lumen narrowing and need for subsequent distal

stent graft extension. Post–stent graft extension showed persistent

narrowing (arrow) at the site of SINE due to insufficient mechanical

support from the fabric between the nitinol rings.

Sinus-XL is a self-expanding uncovered nitinol stent

with a closed-cell design that has been proven to be safe

and durable in treating adult aortic coarctation.[5] Despite

its low profile and the ability to deliver up to 36 mm stent

within a 10-F introducer, we experienced difficulties in

traversing the kink and stent deployment because the

acute angle prevented outer-sheath retraction by the

coaxial pull-back system. This would have been even

more challenging if a similarly sized stent graft had been

chosen since it would have required 20-F access.

Most stent manufacturers discourage operators from

deploying stents across an acute angle due to potential

entrapment of the delivery system. Nonetheless stent

deployment can be facilitated by methods that straighten the target coverage, as in our patient. Other methods

include use of buddy wires or the body flossing technique.

These techniques were less appropriate for our patient

given the recent surgical anastomosis; overcorrecting

the existing anatomy might have increased the risk of

anastomosis-related complications. Moreover, degree of

stent apposition does not necessarily correlate with the

pressure gradient across the kinking, as illustrated in this

case. Thus, in cases of tight stenosis, aggressive balloon

dilatation to pursue a ‘perfectly’ expanded stent may not

be necessary and should be avoided.

In conclusion, FET stent graft kinking is rarely

encountered but can result in significant haemodynamic

consequences. Endovascular stenting is a safe and

effective alternative to surgery. In our patient, we

illustrate the advantages of a BMS over a stent graft

in offering more focal support to the kinked portion

in a low-profile setting. Stenting across the severely

kinked graft can be technically challenging and require

additional manoeuvres, as demonstrated by our case.

To date, no study has compared BMS with covered

stents for treatment of aortic coarctation; head-to-head

bench comparison with reference to radial forces is

also lacking. Although we believe that endovascular

repair can be considered for patients with FET graft

kinking to avoid a second major operation, the decision

to use a BMS or covered stent should be tailored to the

individual and take account of the underlying pathology

and anatomy.

REFERENCES

1. Roselli EE, Bakaeen FG, Johnston DR, Soltesz EG, Tong MZ. Role of the frozen elephant trunk procedure for chronic aortic dissection. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2017;51(suppl 1):i35-9. Crossref

2. Shrestha M, Bachet J, Bavaria J, Carrel TP, De Paulis R, Di Bartolomeo R, et al. Current status and recommendations for use of the frozen elephant trunk technique: a position paper by the Vascular Domain of EACTS. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg.

2015;47:759-69. Crossref

3. Morisaki A, Isomura T, Fukada Y, Yoshida M. Kinking of an open stent graft after total arch replacement with the frozen elephant technique for acute type A aortic dissection. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2018;26:875-7. Crossref

4. Ouzounian M, Hage A, Chung J, Stevens LM, El-Hamamsy I, Chauvette V, et al. Hybrid arch frozen elephant trunk repair: evidence from the Canadian Thoracic Aortic Collaborative. Ann

Cardiothorac Surg. 2020;9:189-96. Crossref

5. Kische S, D’Ancona G, Stoeckicht Y, Ortak J, Elsässer A, Ince H. Percutaneous treatment of adult isthmic aortic coarctation: acute and long-term clinical and imaging outcome with a self-expandable uncovered nitinol stent. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2015;8:e001799. Crossref