Entering the Era of Non-fasting Intravenous Contrast-Enhanced Computed Tomography

PERSPECTVE

Hong Kong J Radiol 2023 Jun;26(2):127-32 | Epub 20 Jun 2023

Entering the Era of Non-fasting Intravenous Contrast-Enhanced Computed Tomography

YS Chan1, CCM Cho1, CSL Tong1, AWH Ng2

1 Department of Imaging and Interventional Radiology, Prince of Wales Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

2 AmMed Medical Diagnostic Center, Hong Kong SAR, China

Correspondence: Dr YS Chan, Department of Imaging and Interventional Radiology, Prince of Wales Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China. Email: juliannayschan@cuhk.edu.hk

Submitted: 2 Mar 2022; Accepted: 17 May 2022.

Contributors: YSC and AWHN designed the study and acquired the data. YSC analysed the data and drafted the manuscript. All authors critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Funding/Support: This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data Availability: All data generated or analysed during the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abstract

An empirical fasting period of at least 4 hours prior to intravenous contrast administration for computed tomography scans has been an age-old practice. This is associated with patient discomfort, adverse effects on diabetic control, and limits the flexibility of scanning arrangements in urgent settings. The effect is further compounded by the rising number of urgent imaging requests with some patients requiring repeated fasting while waiting for scanning slots. International guidelines have been recently updated, stating that with the improved safety profile of contrast media, fasting is no longer routinely required. In this article, we discuss the current evidence and its implications for our local practice. We share our approach of a stepwise policy change with eventual full implementation of non-fasting policy to all eligible patients in our institution, and the safety data we compiled. Adoption of a non-fasting policy for contrast-enhanced computed tomography is a feasible and beneficial practice adhering to international standards.

Key Words: Contrast media; Nausea; Pneumonia, aspiration; Vomiting

中文摘要

進入無需禁食的靜脈顯影電腦斷層掃描的世代

陳奕璇、曹子文、唐倩儂、伍永鴻

電腦斷層掃描靜脈造影劑給藥前至少要求4小時的禁食期一直是一種經驗性做法。這可增加患者不適、不利糖尿病控制,並限制了緊急情況下掃描安排的靈活性。緊急掃描需求數量的增加進一步加劇了這些影響,一些患者在等待掃描時段時需要反覆禁食。最近更新的國際指引指出,隨着造影劑安全性提高,不再需要常規禁食。在本文中,我們討論了當前的證據及其對我們本地實踐的影響。我們分享了我們逐步改變政策的方法最終使我們機構中所有符合條件的患者無需禁食,以及我們收集的安全數據。採用對比顯影掃描的無需禁食政策符合國際標準,且可行有益。

INTRODUCTION

Computed tomography (CT) has been commercially

available since the 1970s and is one of the most widely

used imaging modalities.[1] Conventional intravenous

iodinated contrast emerged in the 1970s to 1980s,

allowing for its application in CT, and is now an almost

indispensable part of daily practice.[2] From then till now,

the contrast agents we use have undergone important

changes.

The intravenous contrast used in CT is iodine-based

and is classified based on osmolality. High-osmolar

contrast media (HOCM) was the first generation of

iodinated intravenous contrast and was associated with

a high rate of adverse events (5%-8% acute adverse

reactions, which essentially encompassed all contrast

reactions, and 1%-2% moderate non–life-threatening

adverse reactions, which included faintness, vomiting

[severe], urticaria [profound], facial edema, laryngeal

edema and bronchospasm [mild]).[3] The majority

of the chemotoxic effects are mainly related to the

hyperosmolality.[3] Nausea and vomiting are common

adverse effects with reported incidences of 4.58% and

1.84%, respectively.[4] Subsequently, since the 1990s,

iso-osmolar contrast media (IOCM) and low-osmolar

contrast media (LOCM), which are associated with

an overall much lower risk of adverse reactions, have

replaced HOCM. A retrospective review by Hunt et al[5]

reported an adverse reaction rate of 0.153% for LOCM

based on 298,491 doses, the prevailing majority of

which were mild reactions not requiring treatment.

The incidences of nausea and vomiting with the use of

non-ionic contrast media (including IOCM and LOCM)

are also substantially lower than their high-osmolar

counterparts, with a reported incidence of 0.05% to

1.99% for nausea, and 0% to 0.36% for vomiting.[6]

Historically, since the days of HOCM use, fasting

has been practised prior to intravenous contrast

administration due to the established emetic side-effects

of HOCM, based on the hypothesis that there is higher

risk of vomiting with a full stomach and to reduce the

risk of aspiration pneumonia. This practice has not been

changed for more than two decades despite the shift to

IOCM and LOCM, until very recently. To date, it is still

a common practice to adopt a period of fasting prior to

contrast media administration before CT scan in Hong

Kong and worldwide.[7] [8]

There has been increasing recognition of the low risk of gastrointestinal side-effects resulting from IOCM and

LOCM administration irrespective of fasting time, as

well as trials abolishing the empirical implementation of

fasting prior to contrast CT. Lee et al[8] reviewed existing

literature and found no case of aspiration in 2001 patients

who underwent contrast CT with prior fluid intake. A

prospective observational study involving 110,836 cases

found no significant difference in the incidence of nausea

and vomiting between solid food non-fasting and fasting

groups.[9] Prospective randomised controlled trials, each

involving more than 2000 patients, were carried out in

both hospitalised patients and outpatients, and found no

significant difference in incidence of nausea and vomiting

between patients fasted for at least 4 hours and patients

without fasting, and no case of aspiration pneumonitis

was identified.[10] [11] There has been an additional report

of a statistically significant reduction in the incidence

of nausea after changing to a non-fasting policy in an

institution in Japan.[12]

Latest Guidelines on Preparatory Fasting

In 2018, the European Society of Urogenital Radiology

(ESUR) published their Guideline on Contrast Agents

(v10.0), which stated that ‘fasting is not recommended

before administration of low- or iso-osmolar non-ionic

iodine-based contrast media or of gadolinium-based

agents’.[13] Later and most recently in 2021, the American

College of Radiology (ACR) published their latest

Manual on Contrast Media, stating that ‘given the

potential for negative consequences due to fasting and

a lack of evidence that supports the need for fasting,

fasting is not required prior to routine intravascular

contrast material administration’, with additional special

consideration required for patients undergoing conscious

sedation.[14]

Local Practice

Currently in Prince of Wales Hospital, the contrast agents used include iohexol 300 and 350 (LOCM), and iodixanol

(IOCM), all of which have a well-established safety

profile and are known to have a low risk of nausea and

vomiting. As per department protocol of the Department

of Imaging and Interventional Radiology at Prince of

Wales Hospital, patients attending the department for

contrast-enhanced CT were previously required to fast

for at least 4 hours prior to study, unless in emergencies

or other limited special considerations. The fasting status

of hospitalised patients would be confirmed by the ward,

and outpatients would receive written instruction to fast

before the appointment.

A PRACTICAL APPROACH TO POLICY CHANGE: LOCAL EXPERIENCE

With the significant discrepancy between the fasting

policy between Prince of Wales Hospital and

international standards, we saw a pressing need to change

our clinical practice. In view of the potential impact

of policy change in terms of logistics, and potential

doubts or confusion from clinical departments in initial

implementation, we adopted a stepwise approach to

policy change, combined with ongoing data collection

to consolidate the local safety profile of contrast media

use under the new policy. The policy change was

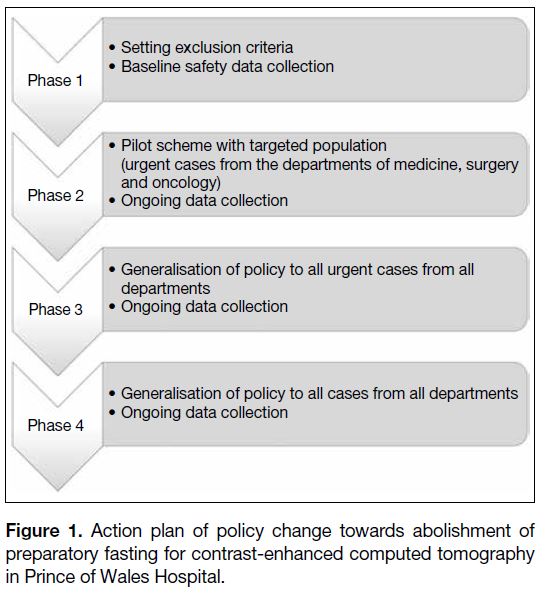

implemented in four phases (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Action plan of policy change towards abolishment of preparatory fasting for contrast-enhanced computed tomography in Prince of Wales Hospital.

Phase 1: Preparatory Phase

We reviewed the potential practical issues to the policy

change. While a generic implementation of the non-fasting

policy would be convenient, we saw that there

would be circumstances and specific indications where

fasting would still be required. As there was no clear

consensus statement or guideline detailing exclusion

criteria to non-fasting policy, we decided on a list

of exclusion criteria based on consensus opinion of

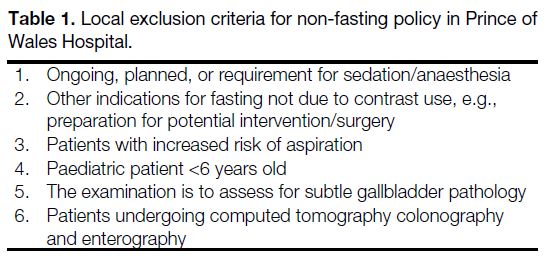

specialists from our local institutes (Table 1).

Table 1. Local exclusion criteria for non-fasting policy in Prince of Wales Hospital.

We gathered data on the fasting time and any occurrence

of vomiting after contrast scanning for the patients coming to the radiology department at Prince of Wales

Hospital for 25 working days through a questionnaire

filled in by attending radiographers and nurses. The

electronic patient record of the patients who experienced

vomiting and their available subsequent chest

radiographs were reviewed to identify any aspiration

pneumonia complications. This served to establish a

baseline of our performance and compile a local safety

profile of contrast media use for CT. After confirming

a comparable incidence of vomiting and aspiration

pneumonia to international published data, we proceeded

with our pilot scheme, continuing to collect data through

all four phases.

Phase 2: Pilot Scheme

We identified the departments of medicine, surgery

and oncology at Prince of Wales Hospital as the three

main sources of referrals to the radiology department

for contrast-enhanced CT. A pilot scheme was then

implemented with these three departments, during

which the referred eligible patients (i.e., those not

under the pre-set exclusion criteria) undergoing urgent

contrast-enhanced CT were not required to fast prior to

examination.

Phase 3: Generalisation of Non-fasting Policy

to Urgent Cases

Subsequent to the pilot scheme, which was well-received

with smooth operation, we proceeded with Phase 3,

which was generalisation of the non-fasting policy

to all urgent cases from all departments. The eligible

patients referred from all departments undergoing urgent

contrast-enhanced CT were not required to fast prior to

examination.

Phase 4: Generalisation of Non-fasting Policy

to All Cases

After allowing for a period of familiarisation of all

departments with the new policy, we entered Phase 4, extending the non-fasting policy to all cases, irrespective

of urgent or elective setting. Previously, all patients

booked for elective contrast-enhanced CT would receive

fasting instructions. After the new policy was enforced,

newly booked patients would no longer receive fasting

instructions unless they fell into the exclusion criteria.

No specific instructions were given to previously booked

patients who had an appointment date after the new

policy launch in order to avoid unnecessary confusion.

For previously booked patients who arrived for contrast-enhanced

CT without adequate fasting but who were not

required to fast under the new policy, the scans were

performed without delay.

Establishing a Local Safety Profile for Intravenous Contrast for Computed Tomography

The same duration (25 working days) and methods of

data collection (questionnaire, electronic patient record,

and chest radiograph review) were applied to Phases 2

through 4.

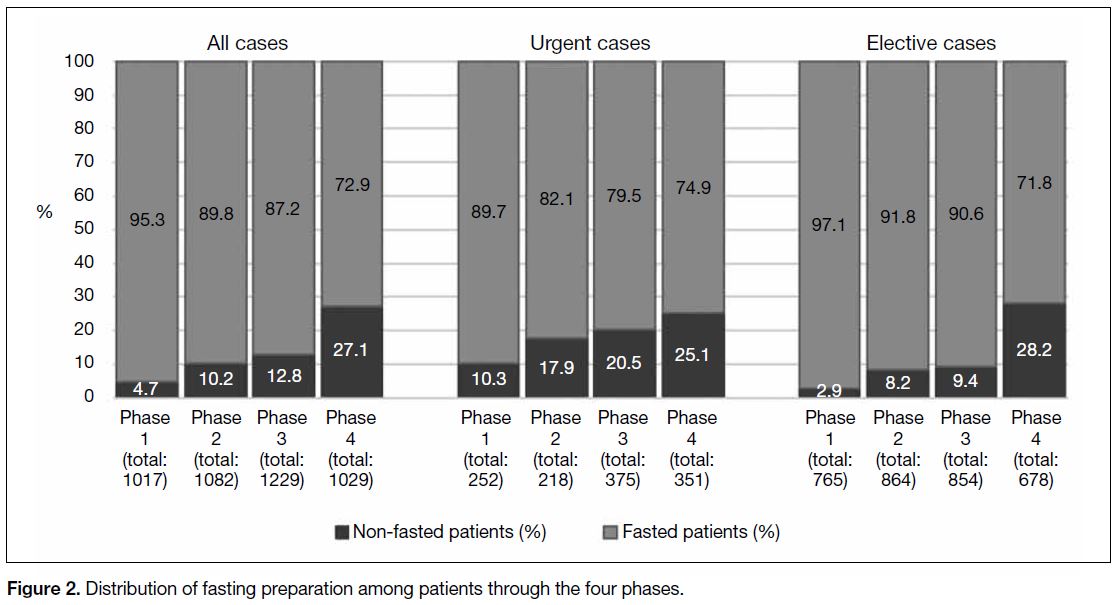

A total of 4357 attendances were recorded during our data collection through the four phases. There was a steady

increase in the proportion of non-fasted attendances

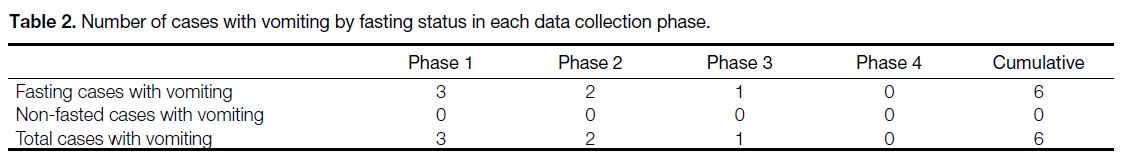

(Figure 2). The incidence of vomiting remained low.

There was a total of six patients who vomited (0.13%),

all of whom had fasted and did not have documented

clinical or radiological evidence of aspiration pneumonia.

A total of 594 patients were non-fasted and no vomiting

occurred (Table 2).

Figure 2. Distribution of fasting preparation among patients through the four phases.

Table 2. Number of cases with vomiting by fasting status in each data collection phase.

DISCUSSION

Internationally, there is a shifting paradigm towards

abolishment of routine preparatory fasting before

intravenous contrast administration for CT scans. The

recent updates in the ESUR guidelines and the ACR

contrast manual provide a clear new international

standard. There is also abundant evidence and

international data confirming the safety profile of use of

IOCM and LOCM, which are the agents used locally. Our

experience with converting to a non-fasting preparation

for contrast-enhanced CT is concordant with the findings of published studies, with a low incidence of vomiting

and no occurrence of aspiration pneumonia. From

a very early study by Oowaki et al[15] to a recent study

by Tsushima et al,[12] longer fasting times were found to

be associated with an increase in the adverse effect of

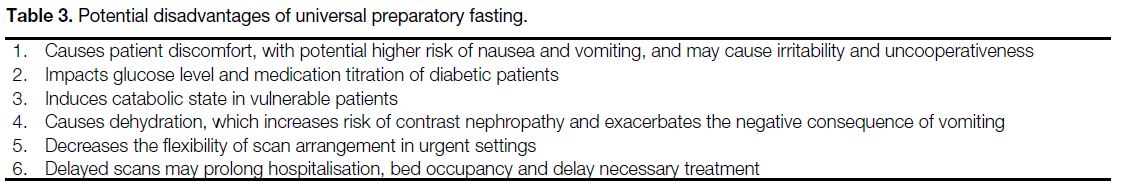

nausea.[15] There are a number of potential disadvantages

of universal preparatory fasting, which are summarised

in Table 3. Fasting creates patient discomfort, disturbs

nutritional balance in the weak, especially older

adult and oncology patients, and potentially causes

negative impact on diabetic control and medication

titration. Fasting may also create dehydration, which

is contradictory to the need of adequate hydration

for prevention of contrast nephropathy, and further

exacerbates the negative fluid balance should vomiting

occur. For inpatients, dehydration can be avoided by

administration of intravenous fluid. For outpatients,

however, intravenous fluid is not a reasonable option.

At an administrative level, the need for consideration of

fasting duration also reduces flexibility in appointment

arrangement. Empirical adherence to preparatory fasting

can lead to unnecessary delays in management, as well

as prolonged hospitalisation and bed occupancy. With

the compelling evidence, a change in local practice is

imperative.

Table 3. Potential disadvantages of universal preparatory fasting.

Practically, the implementation of the non-fasting

policy is not as simple as a one-off policy change, for

two main reasons. First, it is a deeply rooted concept

well-accepted by clinicians in Hong Kong that fasting

has a protective effect against contrast-induced emesis

and lowers the risk of aspiration pneumonia. It is also

a convenient practice as an admission order for the

majority of inpatients to avoid delay in investigations or

potential procedures. However, this practice is not in the

best interest of all patients, especially for the weak and

fragile. In our experience, many inpatients underwent

repeated episodes of prolonged fasting while waiting

for urgent contrast-enhanced CT examinations. Due to

rising demand despite limited resources, this would be

seen more frequently if the policy had not been changed.

Second, it is a general statement that fasting is no longer required prior to contrast administration. There are no

specific exclusion criteria stated by ESUR guidelines,

whereas the ACR manual on contrast media touched

upon that ‘for patients receiving conscious sedation,

anaesthesia guidelines should be consulted’.[13] [14] Despite

the lack of specific instructions, it is imaginable that there

are specific scenarios where fasting may be necessary or

have added benefits. We devised our set of exclusion

criteria locally based on the consensus opinion of our

institutes’ specialists (Table 1). Each institution may

consider a variation of the exclusion criteria tailored to

the demographics of their patients. Our exclusion criteria

have two main bases: (1) There are patients at higher risk

of aspiration; and (2) There are specific needs for fasting

for image optimisation and interpretation.

Specific to certain risk groups, fasting may still be

required. Adding to the ACR manual’s note on patients

undergoing conscious sedation, we expanded the

exclusion to all patients receiving sedation/anaesthesia in

accordance with anaesthesia guidelines for preoperative

fasting, and for those expecting or potentially requiring

sedation/anaesthesia in order to avoid potential delay in

management. A similar rationale was used for patients

expecting to undergo intervention or surgery. On the

other hand, there is a group of patients who are inherently

at higher risk of aspiration, e.g., those with bulbar palsy

with impaired gag reflexes, and those with impaired

consciousness levels. In these groups, the preparatory

fasting aims mainly to reduce the volume of aspirate

should the rare event of vomiting occur, as they are more

vulnerable to the aftermath of vomiting. Another group of

patients requiring special consideration is the paediatric

population. ESUR guidelines[13] and the ACR contrast

manual[14] did not specify a need for special consideration

for the paediatric population. Compared with the adult

population, there are, however, fewer published data

evaluating the risk of vomiting with contrast media use.

A small study by Ha et al[16] involving 864 patients aged

from 1 day to 19 years (mean age = 8.4 ± 5.7 years) found the incidence of vomiting was 2.1% in the study group

with no occurrence of aspiration pneumonia. In Prince

of Wales Hospital, we used the age of 6 years as a cut-off

for the need for fasting in the paediatric population,

based on the need for sedation prior to CT for patients

under this age as suggested by our paediatric radiologist.

Specific to the potential impact on image interpretation,

there has not been any specific dedicated study to

evaluate the effect of a non-fasting policy on image

quality. The gallbladder is known to distend with

fasting, which may allow for better evaluation of

subtle gallbladder pathology, e.g., small polyps. Gross

changes in the gallbladder, e.g., acute cholecystitis,

do not require fasting preparation for assessment. In

addition, the duration of fasting may not necessarily

correlate with the degree of gallbladder distension. We

therefore only limited exclusion to indications to look

for subtle gallbladder pathology. CT enterography and

colonography require bowel preparation for optimal

image quality and accurate image interpretation and

were therefore excluded from the non-fasting policy.

So far, with these exclusion criteria in place, we did not

encounter any case where the interpretation has been

hindered by the non-fasting state.

Combining international guidelines and local consensus

opinion, we have implemented the non-fasting policy to

all patients undergoing iodinated contrast-enhanced CT

examinations in the radiology department with a set of

limited exclusion criteria. Through a stepwise approach,

we allowed time for adaptation and familiarisation by

the clinical departments, and the policy has been met

with a positive response with smooth transition. To our

knowledge, preparatory fasting is still practised in many

local institutions. We hope to advocate the implementation

of a non-fasting policy for eligible patients across centres

in order to provide patient-centred and evidence-based

care, adhering to international standards.

CONCLUSION

Non-fasting contrast-enhanced CT is a safe and

internationally recognised practice supported by evidence

and international guidelines. Our experience showed a

comparable safety profile with that of published studies

in terms of low incidence of vomiting and aspiration

pneumonia. Policy implementation is achievable through

a stepwise approach with need for consideration of pre-set

exclusion criteria.

REFERENCES

1. Schulz RA, Stein JA, Pelc NJ. How CT happened: the early development of medical computed tomography. J Med Imaging (Bellingham). 2021;8:052110. Crossref

2. Nyman U, Ekberg O, Aspelin P. Torsten Almén (1931–2016): the father of non-ionic iodine contrast media. Acta Radiol. 2016;57:1072-8. Crossref

3. Bush WH, Swanson DP. Acute reactions to intravascular contrast

media: types, risk factors, recognition, and specific treatment. AJR

Am J Roentgenol. 1991;157:1153-61. Crossref

4. Katayama H, Yamaguchi K, Kozuka T, Takashima T, Seez P,

Matsuura K. Adverse reactions to ionic and nonionic contrast

media. A report from the Japanese Committee on the Safety of

Contrast Media. Radiology. 1990;175:621-8. Crossref

5. Hunt CH, Hartman RP, Hesley GK. Frequency and severity of

adverse effects of iodinated and gadolinium contrast materials:

retrospective review of 456,930 doses. AJR Am J Roentgenol.

2009;193:1124-7. Crossref

6. Kim YS, Yoon SH, Choi YH, Park CM, Lee W, Goo JM. Nausea

and vomiting after exposure to non-ionic contrast media: incidence

and risk factors focusing on preparatory fasting. Br J Radiol.

2018;91:20180107. Crossref

7. Liu H, Liu Y, Zhao L, Li X, Zhang W. Preprocedural fasting for

contrast-enhanced CT: when experience meets evidence. Insights

Imaging. 2021;12:180. Crossref

8. Lee BY, Ok JJ, Abdelaziz Elsayed AA, Kim Y, Han DH. Preparative fasting for contrast-enhanced CT: reconsideration.

Radiology. 2012;263:444-50. Crossref

9. Li X, Liu H, Zhao L, Liu J, Cai L, Zhang L, et al. The effect of

preparative solid food status on the occurrence of nausea, vomiting

and aspiration symptoms in enhanced CT examination: prospective

observational study. Br J Radiol. 2018;91:20180198. Crossref

10. Neeman Z, Abu Ata M, Touma E, Saliba W, Barnett-Griness O, Gralnek IM, et al. Is fasting still necessary prior to contrast-enhanced computed tomography? A randomized clinical study.

Eur Radiol. 2020;31:1451-9. Crossref

11. Barbosa PN, Bitencourt AG, Tyng CJ, Cunha R, Travesso DJ, Almeida MF, et al. Journal club: preparative fasting for contrast-enhanced CT in a cancer center: a new approach. AJR Am J

Roentgenol. 2018;210:941-7. Crossref

12. Tsushima Y, Seki Y, Nakajima T, Hirasawa H, Taketomi-Takahashi

A, Tan S, et al. The effect of abolishing instructions to fast prior to

contrast-enhanced CT on the incidence of acute adverse reactions.

Insights Imaging. 2020;11:113. Crossref

13. European Society of Urogenital Radiology. Guidelines on Contrast

Agents. 10th ed. Available from: https://adus-radiologie.ch/files/ESUR_Guidelines_10.0.pdf. Accessed 5 Jun 2023.

14. ACR Committee on Drugs and Contrast Media. American College of Radiology. ACR Manual on Contrast Media. 2023. Available from: https://www.acr.org/-/media/ACR/Files/Clinical-Resources/Contrast_Media.pdf. Accessed 16 Apr 2021.

15. Oowaki K, Saigusa H, Ojiri H, Ariizumi M, Yamagisi J, Fukuda K, et al. Relationship between oral food intake and

nausea caused by intravenous injection of iodinated contrast

material [in Japanese]. Nihon Igaku Hoshasen Gakkai Zasshi.

1994;54:476-9.

16. Ha JY, Choi YH, Cho YJ, Lee S, Lee SB, Choi G, et al. Incidence

and risk factors of nausea and vomiting after exposure to lowosmolality

iodinated contrast media in children: a focus on

preparative fasting. Korean J Radiol. 2020;21:1178-86. Crossref