Transradial Diagnostic Cerebral Angiography: Local Experience, Technique, and Outcomes

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Hong Kong J Radiol 2023 Jun;26(2):111-9 | Epub 12 Jun 2023

Transradial Diagnostic Cerebral Angiography: Local Experience, Technique, and Outcomes

HT Lau, YLE Chu, R Lee, WP Cheng, KW Ho

Department of Radiology, Queen Mary Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

Correspondence: Dr YLE Chu, Department of Radiology, Queen Mary Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China. Email: edchu.radiology@gmail.com

Submitted: 23 Oct 2021; Accepted: 4 Mar 2022.

Contributors: All authors designed the study, acquired and analysed the data. HTL and YLEC drafted the manuscript. All authors critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Funding/Support: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data Availability: All data generated or analysed during the present research are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: This research was approved by the Hong Kong West Cluster Research Ethics Committee of Hospital Authority, Hong Kong (Ref No.: HKWC-2021-0649/ UW 21-617). The Ethics Committee waived the need for patient consent for this retrospective study.

Abstract

Introduction

Transradial approach (TRA) has become a popular alternative to traditional transfemoral approach

for catheter cerebral angiography, as it offers advantages such as improved patient comfort, safety profile, and

cost-effectiveness. This study aimed to evaluate the efficacy and safety of ‘radial-first’ approach in diagnostic

neuroangiography in our locality.

Methods

We retrospectively analysed our database of consecutive catheter cerebral angiographies performed via TRA between September 2020 and July 2021. Patient demographics, procedural and radiographic metrics, radial access site–related complications, and total procedural time were recorded.

Results

A total of 52 TRA diagnostic cerebral angiographies were performed. Radial artery access was successfully obtained in all patients (n = 52). The rate of successful navigation through the brachial artery was 98.1% (n = 51), with an overall femoral crossover rate of 1.9% (n = 1). Satisfactory diagnostic images were obtained in all TRA cases (n = 51). Complications related to radial artery access were recorded in two cases (3.8%), including a case of transient radial arterial spasm and a case of transient radial artery occlusion. No access site–related permanent ischaemic symptoms were reported. Other severe access site complications such as pseudoaneurysm and arteriovenous fistula were not demonstrated.

Conclusion

TRA is a safe and feasible technique for diagnostic cerebral angiography in our locality, with a low complication rate.

Key Words: Angiography, digital subtraction; Cerebral angiography; Radial artery

中文摘要

經橈動脈診斷性腦血管造影:本地經驗、技術和結果

劉凱桃、朱賢麟、李雷釗、鄭永鵬、何家慧

引言

經橈動脈入路已成為傳統經股動脈導管腦血管造影術的流行替代方法,因其具有改善患者舒適度、安全性和成本效益等優勢。本研究旨在評估「優先採用經橈動脈入路」方法在我們本地診斷性神經血管造影術中的有效性和安全性。

方法

我們回顧性分析在2020年9月至2021年7月期間通過經橈動脈入路進行連續導管腦血管造影術的數據庫。我們記錄了患者的人口統計資料、手術和影像學指標、經橈動脈入路部位相關併發症和總手術時間。

結果

共進行了52次經橈動脈入路診斷性腦血管造影。所有患者(n = 52)經橈動脈入路插入均成功。通過肱動脈的成功導航率為98.1%(n = 51),一例後續採用了股動脈經路(1.9%)。所有經橈動脈入路病例(n = 51)都獲得了滿意的診斷圖像。兩例(3.8%)發生了與橈動脈通路相關的併發症,包括一例短暫性橈動脈痙攣和一例短暫性橈動脈閉塞。沒有與穿刺部位相關的永久性缺血症狀。未見其他通路部位嚴重併發症如假性動脈瘤和動靜脈等。

結論

經橈動脈入路是本地診斷性腦血管造影安全可行的技術,併發症發生率低。

INTRODUCTION

Catheter cerebral angiography is a common diagnostic

method to examine cerebral vasculature. Traditionally,

the procedures have been performed via the transfemoral

route. However, the transfemoral approach (TFA) is not

always feasible. For example, it will be problematic

in patients with dissection of the thoracic aorta,

iliofemoral occlusive disease, and inguinal infections.

TFA angiography also requires patients to tolerate

uncomfortable groin compression and bed rest after the

procedures. Serious access site–related complications,

including pseudoaneurysm, retroperitoneal haemorrhage,

femoral artery dissection, and lower limb ischaemia are

well recognised.[1] [2] [3] [4]

There has been a notable trend of transition from TFA to

the transradial approach (TRA) in cerebral angiography

among the neuroangiography community. This transition

was primarily fuelled by robust findings of TRA’s

lower access-related complications, lower mortality

rates, decreased length of hospital stay, and increased

patient satisfaction in the cardiology literature.[5] [6] Both

neuroangiography and interventional cardiology require

arterial catheterisation supplying the vital organs which

have narrow margin of error. Also, both of them first

started as TFA. Given these similarities between the

two fields, it was believed that the significant safety advantages of TRA for interventional cardiology might

be transferrable to neuroangiography. This has been

supported by recent data from the neuroangiographic

literature, which have demonstrated favourable safety

profiles, patient experiences, and cost-effectiveness of

TRA over TFA.[3] [7] [8] [9] [10] [11]

In light of the body of evidence demonstrating the clinical benefits of TRA, our centre has adopted a ‘radial-first’

approach in neuroangiography since September 2020.

Here we present our initial experience in the transition

from the traditional TFA to a ‘radial-first’ approach for

diagnostic cerebral angiography, including the technical

feasibility, safety, and complications of the TRA

technique.

METHODS

Study Design

We retrospectively analysed our institutional database of consecutive catheter cerebral angiographies performed

via TRA between September 2020 and July 2021.

Patient demographics, procedural and radiographic

metrics, radial access site–related complications, and

total procedural time were recorded.

Patient selection

All patients underwent preprocedural ultrasound assessment in order to measure the diameter of the right

radial artery and its patency. Patients with a radial artery

diameter of <1.6 mm were excluded and the TFA was

used instead. Patients requiring intervention in addition

to diagnostic angiography were also excluded.

Operators

Transradial cerebral angiographies were performed

by three operators during this time, including a

neuroradiology trainee who had no prior endovascular

experience and performed the procedure under the direct

supervision of one of the two other Hong Kong College

of Radiologists fellowship–qualified radiologists,

who had performed a minimum of 500 TFA cerebral

angiographies each.

Transradial Access Techniques

All TRAs used the right arm as the initial access site. The

radial artery was accessed at a point 1 to 2 cm proximal

to the wrist crease (standard TRA). The more distal

radial artery was accessed at the anatomical snuffbox

site (distal TRA) according to operator’s preference.

The patient was prepared and draped with the right arm

placed at the patient’s right side and the puncture location

exposed. For a standard TRA, the patient’s right distal

forearm and hand were placed in a slightly supinated

position of around 60°. Full supination of the hand can

often result in discomfort and is not necessary. For distal

TRA, the patient’s arm was allowed to rest in a neutral

position and hand supination was not required. A total of

1 to 2 mL of 1% lidocaine was infiltrated into the skin

around the puncture site. Under ultrasound guidance,

the radial artery was punctured using a 20-gauge

needle via Seldinger or modified Seldinger technique

according to the operator’s preference. A 5-F vascular

radial sheath introducer (Glidesheath Slender; Terumo,

Tokyo, Japan or Prelude Radial Sheath; Merit Medical

Systems, Inc, South Jordan [UT], US) was then placed

over an 0.025-inch hydrophilic guidewire (Glidewire

Hydrophilic Coated Guidewire; Terumo, Somerset [NJ],

US). A cocktail containing 3000 units of heparin and

2.0 mg of verapamil diluted with 20 mL of blood prior to

the infusion in order to avoid patient discomfort during

injection was infused over 1 minute through the side-port

of the sheath for antithrombotic and antispasmodic

purposes, respectively. Heparin was withheld in cases

where brain haemorrhage was a concern.

Catheter Navigation and Selection of the

Great Vessels

After TRA was obtained, a 5-F Simmons 2 catheter (S2) (Radifocus Optitorque; Terumo, Somerset [NJ], US) was

navigated over a 0.035-inch guidewire into the ipsilateral

subclavian artery. The navigation of the forearm and

brachium was performed under a monoplane setup with

radial roadmap guidance (Artis zee biplane; Siemens

Healthineers, Erlangen, Germany) in all of our cases,

with the bed at a 10-degree clockwise rotation along

patient’s coronal plane. The radial roadmap is obtained

in order to elucidate any radial artery anomalies and to

avoid lodging the guidewire into small arterial branches

during access to the subclavian. Loops that were

difficult to pass with a 0.035-inch wire were navigated

with a microcatheter system (Progreat Micro Catheter

System; Terumo, Somerset [NJ], US) which would often

straighten out the loop. Once the Simmons catheter was

brought into the subclavian artery, the table was returned

to its neutral position and the lateral plane was brought

into position at 90° to the anteroposterior plane (Artis

zee biplane).

In cases where imaging of the posterior fossa was of

interest, we preferred to first catheterise the right vertebral

artery, as this is often the great vessel encountered

coming in from the right subclavian artery, and its

catheterisation does not usually require reforming the S2

catheter. The catheter was then navigated to the arch to

access the other great vessels. We preferred to reform the

reverse curve of the Simmons catheter in the descending

aorta first whenever possible. In cases where the aorta

was too unfolded or too capacious to allow access to the

descending aorta with the guidewire, we reformed it off

the aortic valve.

Catheterisation and angiograms of the rest of the

great vessels was then performed with a formed S2

catheter. In cases where it was difficult to select the left

vertebral artery, depending on the operator’s preference,

catheterisation of the vessel with a S3 catheter was

attempted. Alternatively, subclavian injection with a

blood pressure cuff around the left arm was performed.

Haemostasis Technique

All arteriotomy closures were achieved with haemostatic

compression bands. In standard TRA, a radial wristband

(TR Band; Terumo, Somerset [NJ], US) was secured

to the arteriotomy site and inflated. The sheath was

then removed with the band inflated. The band was

then slowly deflated until a small amount of bleeding

occurred, after which we injected another 1 to 2 cc of air.

By using the minimum amount of compression needed

for haemostasis, we maximise the chances of preserved radial artery patency. A similar approach is used in the

closure of the distal TRA with a haemostasis device

(PreludeSYNC DISTAL; Merit Medical Systems, Inc,

South Jordan [UT], US).

We followed a departmental protocol for releasing

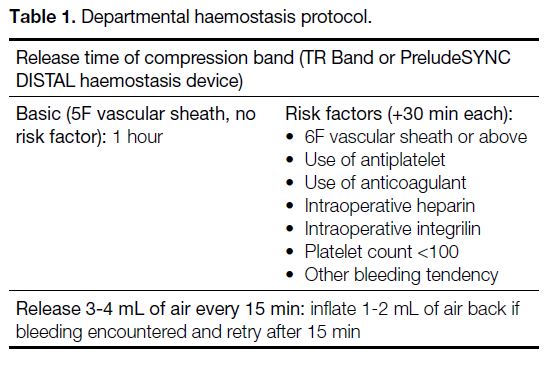

the compression band in the postoperative unit (Table 1).

Table 1. Departmental haemostasis protocol.

RESULTS

A total of 83 patients underwent diagnostic cerebral

angiography in our institution from September 2020

to July 2021. TRA was used as the primary access

technique in 52 patients (19 women and 33 men) with a

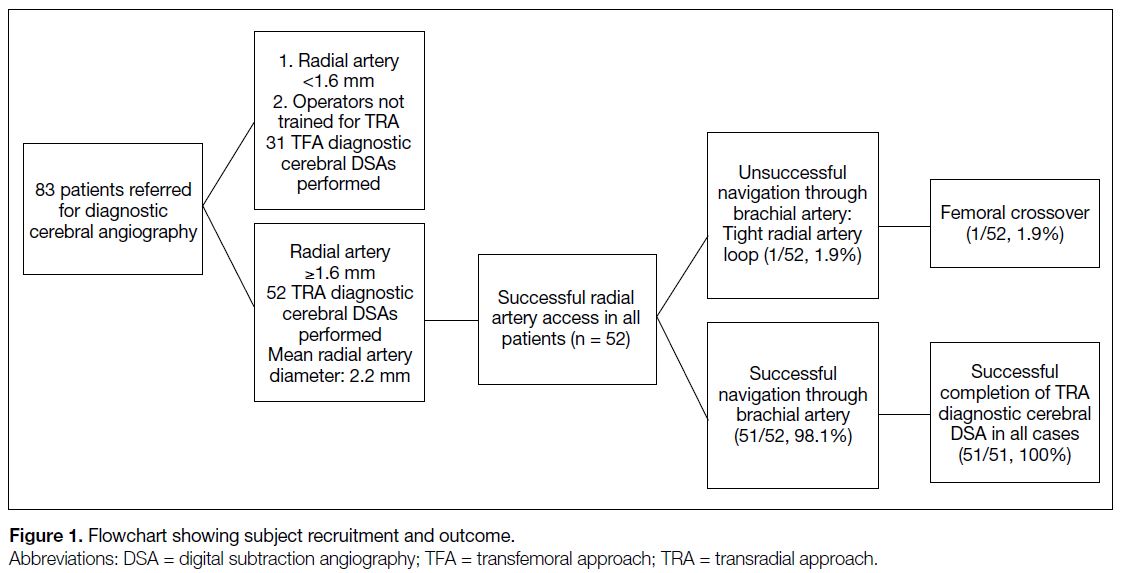

median age of 53 years, ranging from 20 to 81 years. The results are summarised in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Flowchart showing subject recruitment and outcome.

Radial artery access (including standard and distal TRA)

was successfully obtained in all 52 patients. Radial artery

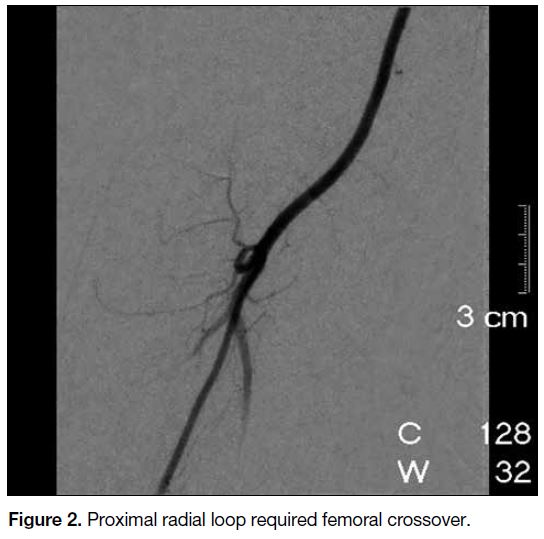

anomalies, including a radial loop (Figure 2) and severe

radial artery tortuosity (Figure 3) were demonstrated

in two cases (3.8%). The rate of successful navigation

through the radial and subsequent brachial artery via TRA

was 98.1% (n = 51). A microcatheter-microwire system

(Progreat Micro Catheter System) was used in one of the

successful cases with severe radial tortuosity. In another

case, a tight loop was encountered in the proximal radial

artery (Figure 2) and the operator decided to crossover

to a TFA.

Figure 2. Proximal radial loop required femoral crossover.

Figure 3. Radial artery tortuosity required microcatheter-microwire system.

Satisfactory diagnostic images were obtained in cases

where catheters were successfully advanced past the

brachial artery (n = 51). None of these cases required

conversion to a TFA. The overall TFA crossover rate

was 1.9% (n = 1) in our cohort.

The mean diameter of the radial artery and distal radial

artery were 2.2 mm (range, 1.6-3.4) and 1.9 mm (range,

1-3), respectively. Distal TRA was attempted in 20

out of 52 cases. Access to the distal radial artery was

unsuccessful in two cases requiring crossover to a

standard TRA. Overall, standard TRA was performed

in 34 cases (65.4%) and distal TRA were performed

in 18 cases (34.6%). The mean diameter of the distal radial artery of successful distal TRAs was 2.2 mm, as

compared to 1.7 mm in the two unsuccessful cases. The

mean diameter of the radial artery in successful standard

TRAs was 2.2 mm.

The mean total procedural time was 45 minutes (range,

7-98), while the mean number of supra-aortic vessel

angiograms performed was 4.7. Choices of diagnostic

catheters for successful angiograms of different vessels

in our series are described in Table 2.

Table 2. Choice of diagnostic catheter used in successful angiograms.

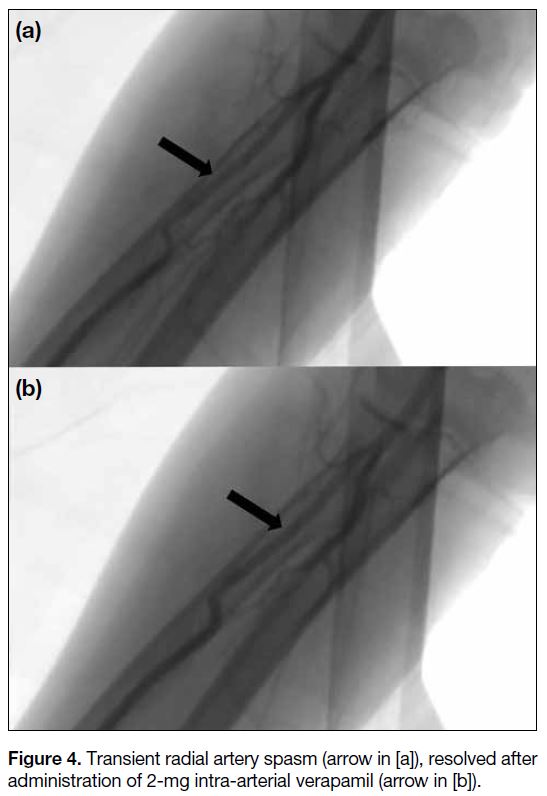

Complications related to radial artery access were

recorded in two cases (3.8%). This included a case

of transient radial arterial spasm (Figure 4) which

was managed with administration of 2-mg intra-arterial

verapamil. The angiogram was successfully

completed after the radial artery spasm was resolved.

No complications were encountered and the patient

was discharged on the day of the procedure. In the

second case (distal TRA), the patient complained of

reduced muscle strength of his right hand and fingers,

which recovered spontaneously over a 2-week period.

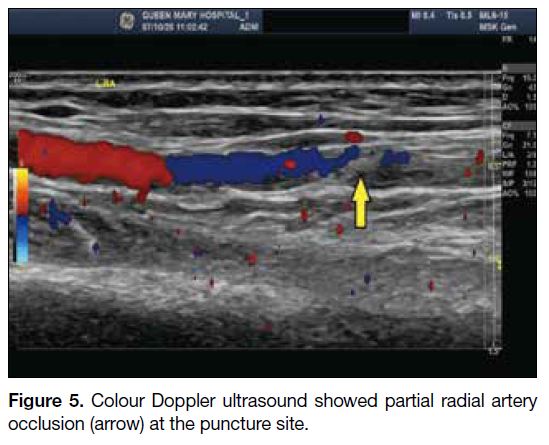

Sonographic assessment at initial presentation showed

partial radial artery occlusion at the puncture site (Figure 5). This was spontaneously resolved together with the

symptoms 2 weeks after the procedure. No access site–related permanent ischaemic symptoms were reported.

Figure 4. Transient radial artery spasm (arrow in [a]), resolved after administration of 2-mg intra-arterial verapamil (arrow in [b]).

Figure 5. Colour Doppler ultrasound showed partial radial artery occlusion (arrow) at the puncture site.

Other severe procedure-related vascular complications

such as pseudoaneurysm, arteriovenous fistula, or

functional disability of the hand described in the

literature[4] [7] [8] were not demonstrated in our series.

In all, 38 patients underwent elective TRA diagnostic

cerebral angiography and 13 cases were performed on an

emergency basis. For elective cases, most of the patients

were discharged on the same day as the procedure

(n = 32, 84.2%), while five were discharged the

following day according to different departmental

practice. One patient, who underwent elective superficial

temporal artery to middle cerebral artery bypass surgery

for moyamoya disease on the same admission, was

discharged 3 days after the TRA procedure.

Overall, a success rate of 98.1% (n = 51) for transradial cerebral angiography was achieved. In the case where the

TRA was unsuccessful, the procedure was completed via

TFA, for an overall crossover rate to femoral approach of

1.9%. Cerebral angiograms were successfully obtained

in all cases when catheters were able to be advanced

beyond the brachial artery. The radial access site–related

complication rate was 3.8%.

DISCUSSION

Transradial Approach Benefits

All patients who underwent TRA cerebral angiography

in an outpatient setting were ambulatory immediately

after the procedure and most of them could be discharged

on the same day.

It is well-established that observation time after

TRA cerebral angiography is significantly shortened

as compared to TFA; this in turn reduces nursing

workload and hospital costs.[9] TRA is also associated

with significantly fewer access site complications.[11]

Uncomfortable groin compression and prolonged bed

rest can be avoided for TRA procedures.

Preprocedural Collateral Circulation

Assessment

We do not routinely perform preprocedural collateral

testing such as Barbeau or Allen tests in accordance with

recommendations from the American Heart Association,

as they have been proven to be unreliable in predicting

the incidence of hand ischaemia.[12] [13] [14]

Radial Cocktail

Nitroglycerine is one of the most common vasodilators

applied prophylactically to prevent radial artery

vasospasm.[3] [7] [10] [15] However, its use in patients with

potential neurovascular disease such as carotid stenosis

may lead to complications such as transient ischaemic

attack or even haemodynamic stroke due to an abrupt

fall in blood pressure.[16] [17] In our centre, we only included

2 mg of verapamil and 3000 units of heparin as a

standard radial cocktail to reduce the risk of vasospasm

during TRA. Overall, the rate of vasospasm, radial

access site complications, and femoral crossover were

all comparable to recent large-scale trials involving TRA

cerebral angiograms with prophylactic nitroglycerine.[3] [7] [10]

Radial Artery Anomaly and Technical

Challenges

Anomalous radial artery anatomy, including a radial

loop, high-bifurcating radial origin, arterial tortuosity,

atherosclerosis, and accessory branches, is relatively

common. A recent study of 1540 patients reported the

overall incidence of radial artery anomalies was 13.8%,

and procedural failure was far more common in patients

with anomalous anatomy than in patients with normal

anatomy.[18]

A radial roadmap was essential in identifying difficult

radial anatomy and therefore performed in all of our

cases. We encountered three cases of difficult radial

artery anatomy, including two cases of radial artery

anomalies (radial loop and severe radial tortuosity) and

a case of radial artery spasm despite pretreatment with

verapamil and heparin.

For the patient with severe radial tortuosity, a

microcatheter-microwire system (Progreat Micro

Catheter System) was used to overcome the tortuous

vessel. An additional 2-mg intra-arterial verapamil dose

was used in the case with radial artery spasm. Successful

TRA cerebral angiography was subsequently performed

in both cases.

One patient failed TRA due to the presence of a tight radial loop. In retrospect, it is possible that this could

have been resolved with the use of a microcatheter or

soft tip guidewire.

Choices of Diagnostic Catheter

The 5-F S2 catheter was our catheter of choice for

diagnostic cerebral angiography, similar to many other

centres worldwide.[7] [8] [19] First-pass success rate was 82.4%

(n = 42) of the cases. With the aid of a 5-F Glidecath

Hydrophilic Coated Catheter (Terumo, Somerset [NJ],

US) in S2 tip shape, 88.2% (n = 45) of cases were

completed. In our series, the right common carotid artery,

both internal carotid arteries, the right external carotid

artery, and both subclavian arteries were all successfully

cannulated by either a S2 or Glidecath (in S2 tip shape)

catheter.

The vertebral arteries are often different in diameter,

with the left side more frequently being dominant.[20] The

success rate of direct left vertebral artery catheterisation

from a right radial approach is known to be lower

compared to that of the rest of the great vessels.[19]

Specifically, the passage of a diagnostic catheter from

the aortic arch to the left vertebral artery through the

left subclavian artery could be difficult, and the success

rate depends on the angle of origin of the left vertebral

artery.[21] Successful left vertebral artery catheterisation is

less likely if the angle between the left vertebral artery

and left subclavian artery is <90°.[21]

In our series, 91.3% (21 out of 23) of left vertebral artery

angiograms were performed with a S2 or Glidecath (in S2

tip shape) catheter. The other two cases were performed

with S1 (Radifocus Optitorque; Terumo, Somerset [NJ],

US) and S3 (SIM3, Torcon NB Advantage Catheter;

Cook Medical, Bloomington [IN], US) catheters,

respectively. There was difficulty in forming the S2

curve in the descending arch in one patient, and the

operator therefore switched to a S1 catheter to cannulate

the left-sided supra-aortic vessels, including the left

vertebral artery. In another case, a S3 catheter was used

to perform a left vertebral artery angiogram as the S2

catheter failed to catheterise the vessel securely.

Haemostasis Protocol

All arteriotomy closures were achieved with a haemostatic compression band as mentioned (Table 1). None of our

patients experienced severe bleeding complications at

the radial artery access site, such as pseudoaneurysm or

significant haematoma.

Limitations

Our study had some limitations, including its

retrospective design and small sample size. Larger-scale

studies are needed to validate our initial findings.

CONCLUSION

TRA is a safe and feasible way for diagnostic cerebral

angiographies, with a low complication rate.

REFERENCES

1. Heiserman JE, Dean BL, Hodak JA, Flom RA, Bird CR, Drayer BP, et al. Neurologic complications of cerebral angiography. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1994;15:1408-11.

2. Ricci MA, Trevisani GT, Pilcher DB. Vascular complications of cardiac catheterization. Am J Surg. 1994;167:375-8. Crossref

3. Wang Z, Xia J, Wang W, Xu G, Gu J, Wang Y, et al. Transradial versus transfemoral approach for cerebral angiography: a prospective comparison. J Interv Med. 2019;2:31-4. Crossref

4. Lee DH, Ahn JH, Jeong SS, Eo KS, Park MS. Routine transradial access for conventional cerebral angiography: a single operator’s experience of its feasibility and safety. Br J Radiol. 2004;77:831-8. Crossref

5. Bertrand OF, Bélisle P, Joyal D, Costerousse O, Rao SV, Jolly SS, et al. Comparison of transradial and femoral approaches for percutaneous coronary interventions: a systematic review and hierarchical Bayesian meta-analysis. Am Heart J. 2012;163:632-48. Crossref

6. Bertrand OF, Patel T. Radial approach for primary percutaneous coronary intervention: ready for prime time? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60:2500-3. Crossref

7. Jo KW, Park SM, Kim SD, Kim SR, Baik MW, Kim YW. Is transradial cerebral angiography feasible and safe? A single center’s experience. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2010;47:332-7. Crossref

8. Matsumoto Y, Hongo K, Toriyama T, Nagashima H, Kobayashi S. Transradial approach for diagnostic selective cerebral angiography: results of a consecutive series of 166 cases. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2001;22:704-8.

9. Romano DG, Frauenfelder G, Tartaglione S, Diana F, Saponiero R. Trans-radial approach: technical and clinical outcomes in neurovascular procedures. CVIR Endovasc. 2020;3:58. Crossref

10. Park JH, Kim DY, Kim JW, Park YS, Seung WB. Efficacy of transradial cerebral angiography in the elderly. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2013;53:213-7. Crossref

11. Tso MK, Rajah GB, Dossani RH, Meyer MJ, McPheeters MJ, Vakharia K, et al. Learning curves for transradial access versus transfemoral access in diagnostic cerebral angiography: a case

series. J Neurointerv Surg. 2022;14:174-8. Crossref

12. Mason PJ, Shah B, Tamis-Holland JE, Bittl JA, Cohen MG,

Safirstein J, et al. An update on radial artery access and best

practices for transradial coronary angiography and intervention in

acute coronary syndrome: a scientific statement from the American

Heart Association. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2018;11:e000035. Crossref

13. Bertrand OF, Carey PC, Gilchrist IC. Allen or no Allen: that is the question! J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:1842-4. Crossref

14. Valgimigli M, Campo G, Penzo C, Tebaldi M, Biscagllia S, Ferrari R, et al. Transradial coronary catheterization and intervention across the whole spectrum of Allen test results. J Am

Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:1833-41. Crossref

15. da Silva RL, Luciano LS, Moreira DM, Fattah T, Trombetta AP, Panata L, et al. Randomised clinical trial comparing transradial catheterisation with or without prophylactic nitroglycerin. Br J Cardiol. 2017;24:100-4.

16. Ruff RL, Talman WT, Petito F. Transient ischemic attacks

associated with hypotension in hypertensive patients with carotid

artery stenosis. Stroke. 1981;12:353-5. Crossref

17. Belcaro G, Marchionno L. Hypotension as cause of TIAs (transient

ischemic attacks) in patients with severe carotid stenosis and

hypertension. Acta Chir Belg. 1983;83:436-8.

18. Lo TS, Nolan J, Fountzopoulos E, Behan M, Butler R,

Hetherington SL, et al. Radial artery anomaly and its influence on

transradial coronary procedural outcome. Heart. 2009;95:410-5. Crossref

19. Layton KF, Kallmes DF, Cloft HJ. The radial artery access site for interventional neuroradiology procedures. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2006;27:1151-4.

20. Hong JM, Chung CS, Bang OY, Yong SW, Joo IS, Huh K. Vertebral artery dominance contributes to basilar artery curvature and peri-vertebrobasilar junctional infarcts. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2009;80:1087-92. Crossref

21. Luo N, Qi W, Tong W, Meng B, Feng W, Zhou X, et al. The effect of vascular morphology on selective left vertebral artery catheterization in right-sided radial artery cerebral angiography. Ann Vasc Surg. 2019;56:62-72. Crossref