Eosinophilic Meningitis and Pneumonitis due to Angiostrongyliasis: a Case Report

CASE REPORT

Eosinophilic Meningitis and Pneumonitis due to Angiostrongyliasis: a Case Report

YM Leng, Allen Li

Department of Radiology and Nuclear Medicine, Tuen Mun Hospital, Hong Kong

Correspondence: Dr YM Leng, Department of Radiology and Nuclear Medicine, Tuen Mun Hospital, Hong Kong. Email:

Submitted: 22 May 2020; Accepted: 7 Oct 2020.

Contributors: Both authors designed the study, acquired the data, analysed the data, drafted the manuscript, and critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. Both authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of Interest: Both authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Funding/Support: This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data Availability: All data generated or analysed during the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: The study was approved by New Territories West Cluster Research Ethics Committee of Hospital Authority (Ref No.: NTWC/REC/20052). The patient was treated in accordance with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki and has provided written informed consent for all treatments and procedures. Patient consent for this study was waived by the Committee.

INTRODUCTION

Angiostrongylus cantonensis infection is one of the most common causes of eosinophilic meningitis in

Southeast Asia and the Pacific Basin.[1] The organism was

first described in 1935 by Chinese parasitologist Hsin-tao

Chen. It was first found in the cerebrospinal fluid

(CSF) of a Japanese patient who died of eosinophilic

meningoencephalitis in Taiwan in 1944.[2] Since then,

there has been an increase in the global distribution of

reported cases. Sporadic cases in travellers who have

returned from endemic areas have been reported.

Infection with A cantonensis can arise from ingestion of

food items contaminated by intermediate or definitive

hosts. Neural tissue can be targeted after infection. Lung

involvement is less commonly encountered clinically.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first reported

local case of A cantonensis infection with both central

nervous system and lung involvement.

CASE PRESENTATION

A 29-year-old Chinese man with a history of epileptic

seizure since childhood was admitted to Tuen Mun

Hospital with a 5-day history of severe cerebellar ataxia, preceded by a 3-day history of fever and mild dry cough

after travelling to Japan. On admission, he was afebrile

with a right-hand intentional tremor, pass pointing

sign, and tandem walking instability. No neck rigidity

was detected. His Glasgow Coma Scale score was 15.

Computed tomography (CT) of the brain on admission

was essentially normal.

Initial lumbar puncture revealed elevated opening

pressure and a CSF white blood count of 257/μL,

with 96% lymphocytes and 4% polymorphonuclear

leucocytes. Cryptococcal antigen, bacterial culture

and sensitivity test, CSF Japanese encephalitis virus

antigen, Mycobacterium tuberculosis polymerase chain

reaction (PCR), and CSF viral PCR test results were

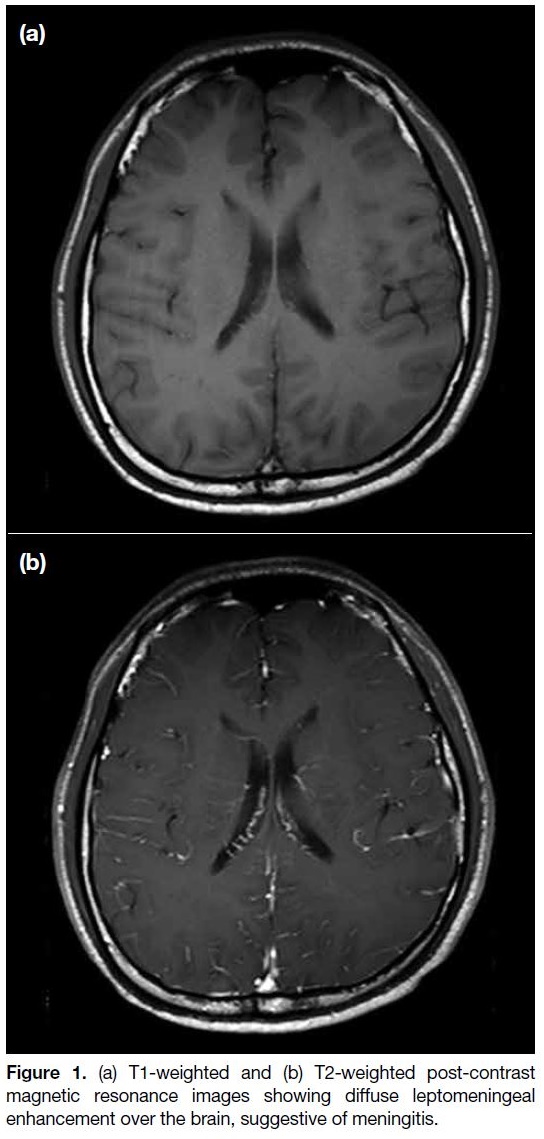

all negative. Subsequent magnetic resonance imaging

(MRI) of the brain (Figure 1) showed diffusely increased

leptomeningeal enhancement, suggestive of meningitis.

MRI of the whole spine showed no abnormal signal

along the spinal cord. A new lumbar puncture revealed

escalating white cell count from 257 to 2049/μL. Repeat

CSF viral, bacterial, and fungal test results were again

all negative.

Figure 1. (a) T1-weighted and (b) T2-weighted post-contrast

magnetic resonance images showing diffuse leptomeningeal

enhancement over the brain, suggestive of meningitis.

However, peripheral blood eosinophil count

progressively increased to 33.3% (normal <6%). A third

lumbar puncture demonstrated eosinophilia, and a PCR

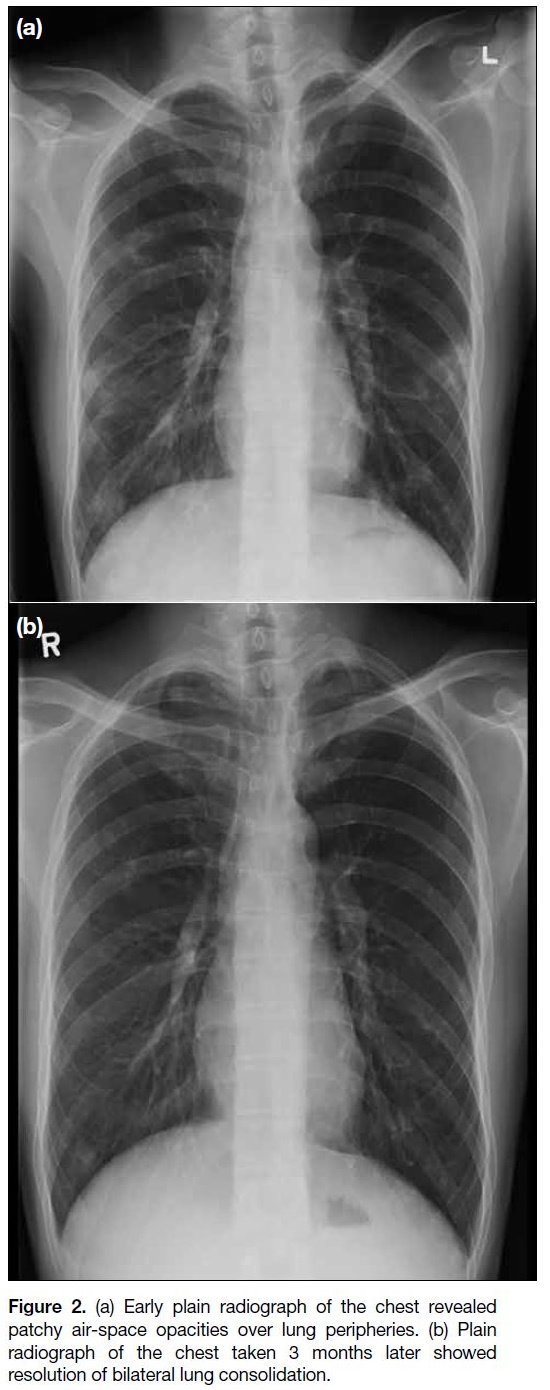

test for Angiostrongylus spp. was positive. Plain chest

radiograph on admission had revealed patchy infiltrates

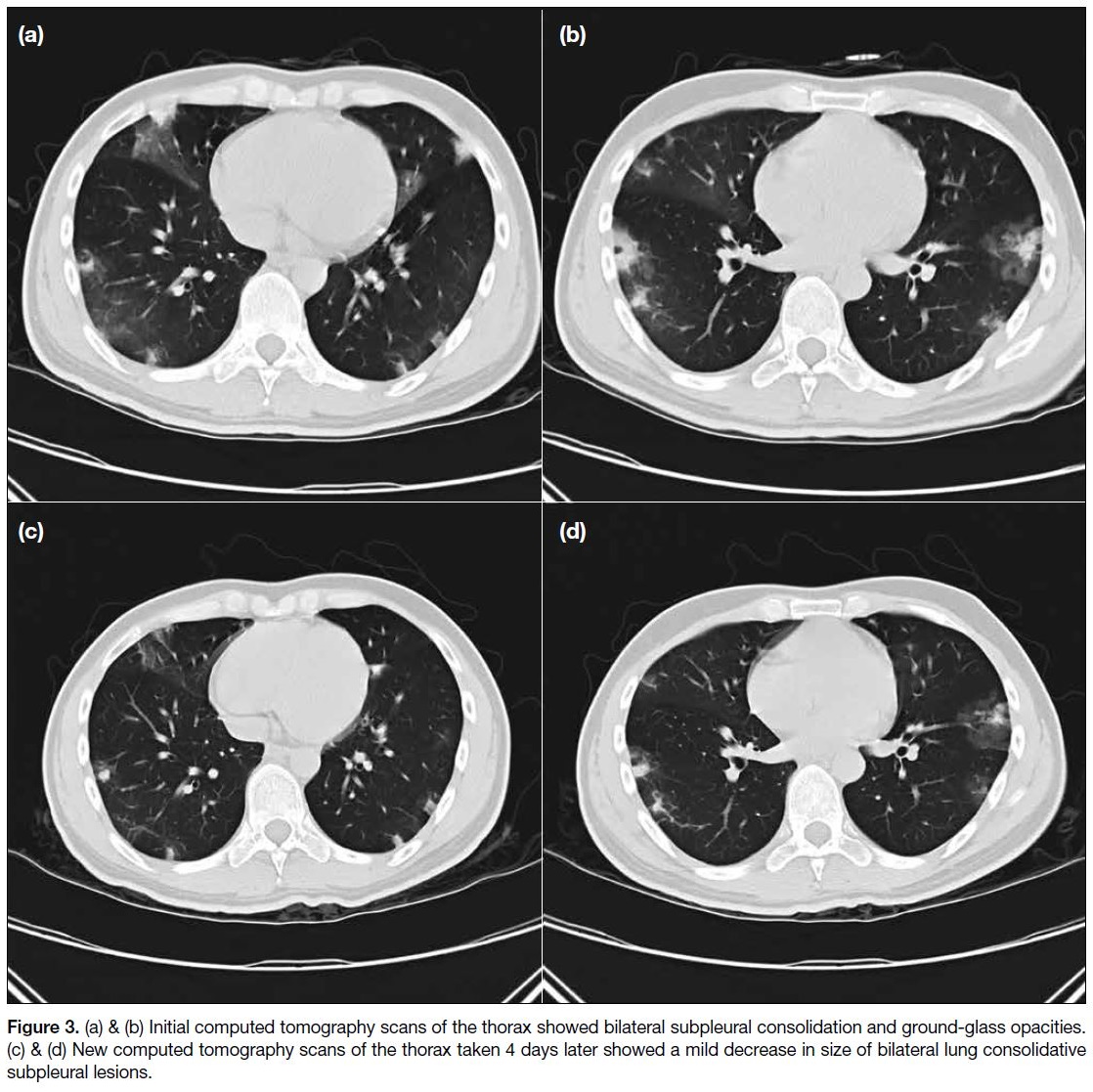

over peripheral lung fields (Figure 2). CT scan of the

thorax showed bilateral subpleural consolidation and

ground-glass opacities (Figure 3). Of note was the

presence of the halo sign in some areas, that is ground-glass

opacity surrounding some of the consolidative lesions.

Figure 2. (a) Early plain radiograph of the chest revealed

patchy air-space opacities over lung peripheries. (b) Plain

radiograph of the chest taken 3 months later showed

resolution of bilateral lung consolidation.

Figure 3. (a) & (b) Initial computed tomography scans of the thorax showed bilateral subpleural consolidation and ground-glass opacities.

(c) & (d) New computed tomography scans of the thorax taken 4 days later showed a mild decrease in size of bilateral lung consolidative

subpleural lesions.

The patient was prescribed empirical antibiotics,

antiviral treatment, and analgesics with gradual clinical

improvement. He was not immunocompromised after work-up and was discharged after 4 weeks, with follow-up

CT scan of the thorax during admission (Figure 3)

and chest radiograph after discharge showing resolution

of the lung lesions (Figure 2). His fever had resolved,

and no headache or neurological signs were evident.

Peripheral eosinophil count was decreasing.

DISCUSSION

A cantonensis primarily infects rat lungs. First-stage larvae migrate to the pharynx where they are swallowed

and excreted via the faeces. Intermediate hosts such as

snails ingest the faeces of rodents contaminated by these first-stage larvae that then moult twice within the mollusc

to develop into second- and third-stage larvae. The third-stage

larva is the infecting form of the parasite. Human

infection can occur after ingestion of undercooked

snails, or through ingestion of unwashed salads or raw

vegetable juice contaminated with infective third-stage

larvae.[3]

Once infective third-stage larvae are ingested, they can

invade the gastrointestinal system and cause enteritis.

The larvae then pass through the liver and lungs before

reaching the nervous system. Symptoms that include cough, sort throat, and fever develop as the nematode

moves through the lungs. The neurological manifestations

of A cantonensis infection include eosinophilic

meningitis, encephalitis or encephalomyelitis, radiculitis,

cranial nerve abnormalities, and ataxia.

Angiostrongyliasis should be considered in patients with

high eosinophil count in blood and/or CSF. The diagnosis

of angiostrongyliasis is confirmed by detection of A

cantonensis antigen or antibody in blood or CSF. PCR

for antigen detection in CSF has recently been developed

and may help to confirm diagnosis at an earlier stage.[4] In

our case, the patient had a high eosinophil count in blood

and CSF. The CSF PCR confirmed the diagnosis.

MRI examination of the brain and spinal cord in our

patient showed diffuse leptomeningeal enhancement of

the brain only. There was no abnormal enhancement of

the spinal cord on MRI study. In a case series with 17

MRI examinations of the brain and spinal cord in five

patients with angiostrongyliasis, multiple enhancing

nodules in the brain and linear enhancement in the

leptomeninges were the main imaging findings.[5] Spinal

cord involvement with enhancement of the nerve roots

can also occur but is rare.[5] In a study of 27 patients

who were clinically diagnosed with angiostrongyliasis,

MRI findings included leptomeningeal enhancement,

thickening of the meninges, intracranial nodules, and

perimeningeal vascular thickening.[6]

The CT thorax in our patient showed diffuse bilateral

subpleural consolidations with ground-glass halo sign.

In another study, CT thorax in 15 patients revealed

pulmonary nodular lesions and ground-glass opacity

lesions located in the subpleural area, which are

characteristic signs of the disease.[7] In a case series of

12 patients with lung involvement, CT findings included

small nodules with or without a halo of ground-glass

attenuation, patchy areas of ground-glass attenuation

and focal thickening of bronchovascular bundles

located mainly in the peripheral lungs.[8] A large series of

81 patients with A cantonensis infection showed

concordant imaging findings of focal leptomeningeal

enhancement on MRI brain (n = 36) and lung nodules

and ground-glass opacity (n = 18).[9]

The diagnosis of angiostrongyliasis can be difficult

and requires a high level of suspicion. Clinical history

is very important, particularly a history of travel to

endemic regions or ingestion of commonly infested

host. The diagnosis should be suspected in patients with eosinophilic meningoencephalitis with elevated

eosinophils in the blood and/or CSF. MRI brain finding

of leptomeningeal enhancement is non-specific. A

cantonensis can be associated with focal brain lesions on

imaging but less commonly than with other helminthic

infections of the central nervous system (gnathostomiasis

or neurocysticercosis).[10] [11] [12] Lung findings of subpleural

consolidation and ground-glass opacities, some with

halo sign, are also non-specific and can be found in

various diseases ranging from infection or neoplasia to

inflammatory conditions. Although many cases are self-limiting,

severe neurological sequelae and even death

may occur.

In summary, we report a case of angiostrongyliasis

involvement of the brain and lung. Early recognition and

accurate detection of A cantonensis can improve patient

outcomes. It is important to raise public awareness of

disease risk factors in endemic areas and international

travellers to prevent further transmission.

REFERENCES

1. Baheti NN, Sreedharan M, Krishnamoorthy T, Nair MD, Radhakrishnan K. Neurological picture. Eosinophilic meningitis

and an ocular worm in a patient from Kerala, south India. J Neurol

Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2008;79:271. Crossref

2. Nomura S, Lin H. First clinical case of Haemostrongylus ratti. Taiwan No Ikai. 1945;3:589-92.

3. Tsai HC, Lee SS, Huang CK, Yen CM, Chen ER, Liu YC. Outbreak of eosinophilic meningitis associated with drinking raw vegetable juice in southern Taiwan. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2004;71:222-6. Crossref

4. Ansdell V, Wattanagoon Y. Angiostrongylus cantonensis in travelers: clinical manifestations, diagnosis, and treatment. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2018;31:399-408. Crossref

5. Jin E, Ma D, Liang Y, Ji A, Gan S. MRI findings of eosinophilic myelomeningoencephalitis due to Angiostrongylus cantonensis. Clin Radiol. 2005;60:242-50. Crossref

6. Yang B, Yang L, Chen Y, Lu G. Magnetic resonance imaging findings and clinical manifestations in cerebral angiostrongyliasis

from Dali, China. Brain Behav. 2019;9:e01361. Crossref

7. Cui Y, Shen M, Meng S. Lung CT findings of angiostrongyliasis cantonensis caused by Angiostrongylus cantonensis. Clin Imaging. 2011;35:180-3. Crossref

8. Cheng J, Huang H, Wang X, Wu A, Yu Z, Xu F, et al. Angiostrongylus cantonensis: chest CT findings [in Chinese]. Chin J Radiol. 1999;33:371-3.

9. Wang J, Zheng X, Yin Z, Qi H, Li X, Ji A, et al. A clinical analysis of 81 cases of Angiostrongylus cantonensis in Beijing [in Chinese]. Chin J Intern Med. 2008;1:50-1.

10. Diaz JH. Recognizing and reducing the risks of helminthic eosinophilic meningitis in travelers: differential diagnosis, disease management, prevention, and control. J Travel Med. 2009;16:267-75. Crossref

11. Wang QP, Lai DH, Zhu XQ, Chen XG, Lun ZR. Human angiostrongyliasis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2008;8:621-30. Crossref

12. Ramirez-Avila L, Slome S, Schuster FL, Gavali S, Schantz PM, Sejvar J, et al. Eosinophilic meningitis due to Angiostrongylus and Gnathostoma species. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48:322-7. Crossref