Neoadjuvant Treatment of Locally Advanced Rectal Cancer in Elderly Patients: Real-World Experience at a Tertiary Institution

ORIGINAL ARTICLE CME

Neoadjuvant Treatment of Locally Advanced Rectal Cancer in Elderly Patients: Real-World Experience at a Tertiary Institution

GTC Cheung1, EYH Chuk1, KM Cheung1, JCH Chow1, L Fok2, HL Leung2, CC Law1

1 Department of Clinical Oncology, Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Hong Kong

2 Department of Oncology, United Christian Hospital, Hong Kong

Correspondence: Dr GTC Cheung, Department of Clinical Oncology, Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Hong Kong. Email: ctc069@ha.org.hk

Submitted: 14 Jun 2022; Accepted: 23 Oct 2022.

Contributors: GTCC designed the study and acquired the data. All authors analysed the data. GTCC, EYHC, KMC and JCHC drafted the

manuscript. All authors critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of Interest: As an editor of the journal, GTCC was not involved in the peer review process. Other authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Funding/Support: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data Availability: All data generated or analysed during the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: This research was approved by the Research Ethics Committee (Kowloon Central/Kowloon East Cluster) of Hospital Authority, Hong Kong (Ref: KC/KE-21-0264/ER-3) and was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent of patients

was waived because of the retrospective nature of the study.

Abstract

Introduction

The incidence of rectal cancer increases with age. Neoadjuvant radiotherapy, with or without concurrent

chemotherapy, has been shown to improve outcomes. Elderly patients are underrepresented in clinical trials. In

Hong Kong, there is a lack of consensus and local data to inform patient selection and formulate optimal treatment

strategies for them. We sought to examine the outcomes of elderly patients undergoing neoadjuvant treatment for

locally advanced rectal cancer.

Methods

Cases of patients with locally advanced rectal cancers who received neoadjuvant treatment in Department

of Clinical Oncology, Queen Elizabeth Hospital from 2015 to 2018 were reviewed. ‘Elderly patient’ was defined as

those ≥70 years at diagnosis. The key study endpoints were local relapse-free survival (RFS), regional RFS, distant

RFS, overall RFS, and overall survival. Other endpoints included rate of downstaging, rate of conversion from

threatened/involved margins to clear margins, and treatment-related toxicities.

Results

In all, 74 elderly patients and 142 non-elderly patients were identified. The proportion of patients receiving

concurrent chemotherapy during radiotherapy was lower in the elderly patients (p < 0.001). Chemoradiation

administered to patients of all ages did not result in statistically significant differences in any survival endpoint.

Elderly patients deemed unfit for concurrent chemotherapy had a higher incidence of treatment toxicities. Age was

not a significant prognostic factor in any categories of survival.

Conclusion

Age should not be a deterministic factor in treatment planning in locally advanced rectal cancer.

Satisfactory oncological outcomes can be achieved in selected elderly patients. Utilisation of geriatric assessment

and consideration of patients’ preference are required to optimise treatment outcomes.

Key Words: Aged; Chemoradiotherapy; Neoadjuvant therapy; Radiotherapy; Rectal cancers

中文摘要

局部晚期直腸癌年老病人的術前輔助治療:第三層醫療機構的實際經驗

張天俊、祝菀馨、張嘉文、周重行、霍善智、梁海量、羅志清

簡介

直腸癌發病率隨年齡增長而上升。已有研究顯示術前輔助放射治療(不論有否同步進行化學治療)能改善病情。年老病人在臨床測試中的代表性不足。在香港,在選取病人及為該類病人制訂最佳治療策略方面,醫學界尚未達成共識,本地數據亦不足。我們嘗試分析進行局部晚期直腸癌術前輔助治療的年老病人的病情。

方法

本研究回顧了於2015至2018年期間在伊利沙伯醫院臨床腫瘤科接受術前輔助治療的局部晚期直腸癌病人個案。「年老病人」的定義為於確診時年屆70歲或以上的病人。關鍵研究終點為無局部復發存活、無區域復發存活、無遠處轉移存活、整體無復發生存率及總生存率。其他研究終點包括癌症降期率、從受威脅/侵犯切緣轉為陰性切緣率及治療相關毒性。

結果

我們分析了74名年老病人及142名非年老病人。年老病人在接受放射治療期間同時進行化學治療的比例較低(p < 0.001)。為所有年齡的病人進行放化療在任何存活終點並沒有出現統計學上的顯著差異。不適合同時接受化學治療的年老病人,其治療毒性發生率較高。年齡並非任何類別存活的重要預後因素。

結論

在規劃局部晚期直腸癌的治療時,年齡不應被視為決定性因素。部分年老病人可以獲得令人滿意的腫瘤治療結果。要達至最佳治療結果,須使用老年評估及考慮病人的偏好。

INTRODUCTION

According to the latest Hong Kong Cancer Statistics

2019, colorectal cancer ranked second in annual

incidence of neoplasms in Hong Kong.[1] Within the 5556

new cases in 2019, 2072 were rectal/anal malignancies.

Age is an important risk factor for rectal cancers; over

half of the newly diagnosed rectal/anal cancer patients in

2019 were >65 years old.[1]

Surgery is the mainstay of curative treatment for rectal

adenocarcinomas. Extensive research efforts were made

in search of the optimal neoadjuvant therapy modalities

to improve outcomes. The German Rectal Cancer Study

Group’s phase III study published in 2004 set the standard

of neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy for clinical T3/4 or

lymph node positive diseases,[2] and the role of concurrent

chemotherapy during neoadjuvant radiotherapy (RT)

was confirmed in a 2013 Cochrane review in lowering

the incidence of local recurrence.[3] Mesorectal fascial

involvement threatening the circumferential resection

margin (CRM) and distal rectal tumours were included in

international treatment guidelines as relative indications

for neoadjuvant treatment.[4] [5]

Elderly patients were underrepresented in these clinical

trials. Ageing is associated with poor performance status, an increased incidence of comorbidities, and

suboptimal treatment tolerance. Retrospective studies

have investigated the outcomes of elderly patients

undergoing rectal cancer treatments,[6] [7] [8] [9] but conclusions

were divided regarding the adequate methodology of

patient selection, the optimal magnitude of neoadjuvant

treatment in patients with marginal performance status,

and the side-effect profile of this population. There is

also a lack of local data specifically for this controversial

topic. We therefore performed this study to examine the

outcomes of elderly patients undergoing neoadjuvant

treatment for locally advanced rectal cancers.

METHODS

We retrospectively reviewed the medical records

of consecutive patients that received neoadjuvant

treatment for rectal cancer in Department of Clinical

Oncology, Queen Elizabeth Hospital during the period

from 1 January 2015 to 31 December 2018. Patients

were considered for neoadjuvant treatment if they

satisfied the following inclusion criteria: (1) biopsy-proven

adenocarcinoma of rectum (located ≤12 cm

from anal verge); (2) staging by pelvic magnetic

resonance imaging, and either computed tomography

scan covering thorax, abdomen and pelvis, or positron

emitted tomography/computed tomography of the whole body, showing non-metastatic disease that was at

local stage T3 or above by American Joint Committee

on Cancer’s Cancer Staging Manual 7th edition, or

with involved or threatened mesorectal fascia; and (3)

deemed fit for neoadjuvant treatment and subsequent

surgery by the attending physician based on performance

status, age, and comorbidities. The diagnostic scans and

the decision to institute neoadjuvant treatment were

discussed in a multidisciplinary team meeting involving

clinical oncologists, colorectal surgeons, and diagnostic

radiologists.

Neoadjuvant treatment consisted of pelvic RT with or

without concurrent chemotherapy. For RT, gross tumour

volume was determined from clinical data (physical

examination, colonoscopy and imaging findings). Clinical

target volume included gross tumour volume plus a 2-cm

circumferential margin, the entire mesorectum, and high-risk

nodal areas including presacral, mesorectal, obturator,

and internal iliac nodes. A 1-cm circumferential margin

was added to clinical target volume to form the planning

target volume. Patients were treated with long-course

RT with conformal, intensity-modulated radiotherapy

or volumetric modulated arc therapy techniques. A

minimum dose of 45 Gy in 25 fractions was prescribed

to the 100% isodose line; an optional boost to the gross

disease was allowed up to a total equivalent dose of

54 Gy in 30 fractions, either with two-phase techniques

(in conformal RT) or simultaneous integrated boost (in

intensity-modulated radiotherapy/volumetric modulated

arc therapy).

Similar to reported local practice,[10] two regimens of

concurrent chemotherapy were adopted: intravenous

bolus 5-fluorouracil at 500 mg/m2 on Days 1-3 and Days

29-31, or oral capecitabine at 825 mg/m2 twice daily,

5 days per week. Omission of concurrent chemotherapy

due to advanced age, comorbidities, or patient preference

was allowed.

Cross-sectional imaging was repeated at around 4-6

weeks after completion of RT to evaluate treatment

response after neoadjuvant treatment and to assess

operability. If operable, total mesorectal excision was

performed ideally 6-10 weeks after RT completion.

Based on our institution protocol, further adjuvant

chemotherapy was not routinely offered due to the lack

of evidence supporting benefit of adjuvant chemotherapy

in randomised controlled trials and meta-analyses.

After treatment, surveillance was performed with regular history taking, physical examination, carcinoembryonic

antigen monitoring, and surveillance colonoscopy.

Cross-sectional imaging with computed tomography

or positron emitted tomography/computed tomography

scan was arranged when clinically indicated.

In this study, we defined elderly patients as those

≥70 years old at the time of histological diagnosis.

The key endpoints of this study were local relapse-free

survival (RFS), regional RFS, distant RFS, overall RFS,

and overall survival (OS). Other endpoints included

rate of downstaging (both T and N stages) and rate of

conversion from threatened/involved CRM to clear

margins. Treatment-related toxicities were assessed by

the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology

Criteria for Adverse Events version 4.03 and 30-day

postoperative mortality. Data were analysed using

commercial software SPSS (Windows version 24.0;

IBM Corp, Armonk [NY], United States). Baseline

characteristics between groups were tabulated and

compared using the Mann-Whitney U test for continuous

data and the Chi squared test for categorical data.

Survival endpoints were estimated by the Kaplan-Meier

method. Prognostic significance of clinical predictors

was analysed using the log-rank test in simple analysis

and the Cox proportional hazards model in multivariable

regression analysis.

RESULTS

A total of 238 cases of patients with rectal cancer who

received neoadjuvant therapy were identified. Twenty-two

cases were excluded for Stage IV disease at baseline.

A total of 74 of the remaining 216 patients were elderly

patients. Median ages of elderly patients and non-elderly

patients were 76.0 and 61.2 years, respectively. In

total, 91.7% of the patients had an Eastern Cooperative

Oncology Group performance status (ECOG PS) score

of 0-1; a higher proportion of ECOG PS score of 2

was noted in the elderly population (18.9% vs. 2.8%,

p = 0.011). Elderly patients had a significantly higher

prevalence of comorbidities (hypertension: 66.2% vs.

26.8%, p < 0.001; ischaemic heart disease: 16.2% vs.

4.9%, p = 0.019). No statistically significant difference

was noted between elderly and non-elderly groups

in clinical stage or CRM status. The full baseline

demographics and comorbidities before treatment

initiation are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Baseline demographics by age-group and treatment.

A total of 53 elderly patients and six non-elderly

patients had neoadjuvant RT alone; the proportion of

patients who received concurrent chemotherapy was lower in elderly patients than non-elderly patients

(28.4% vs. 95.8%, p < 0.001). The most common

reasons for chemotherapy omission in elderly

patients were advanced age (n = 44, 83%), poor

performance status (n = 4, 7.5%), and patient refusal

(n = 4, 7.5%). Technique of RT, boost dose frequency,

and time of RT completion were similar between elderly

and non-elderly groups.

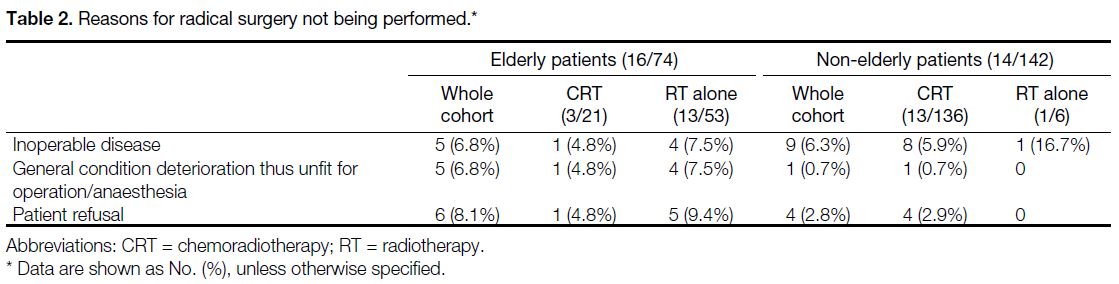

After neoadjuvant treatments, 58 elderly cases (78.4%) and 128 non-elderly (90.1%) cases went on to

undergo radical surgery as planned; 16 elderly patients

(21.6%) and 14 non-elderly patients (9.9%) did not

undergo radical surgery. The reasons are shown in

Table 2. These patients were excluded from survival

analyses but were included in toxicity and safety

analyses.

Table 2. Reasons for radical surgery not being performed.

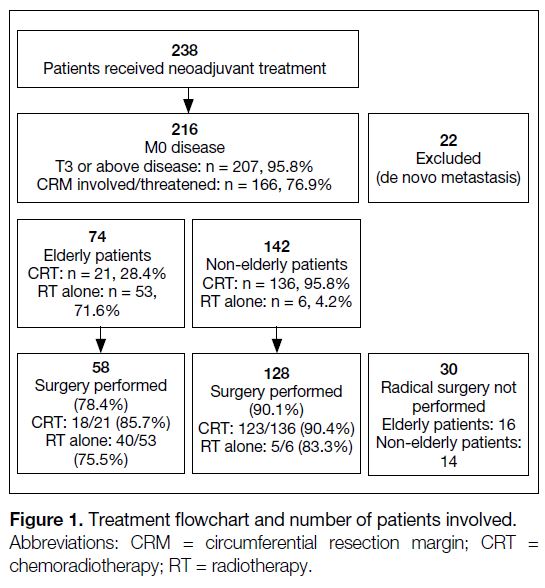

Figure 1 illustrates the treatment scheme with number

of cases involved. The time to radical surgery and the rate of sphincter preservation were similar between

elderly and non-elderly patients. A total of 27 patients

subsequently received further adjuvant chemotherapy

after surgery. Treatment details are listed in the online supplementary Appendix.

Figure 1. Treatment flowchart and number of patients involved.

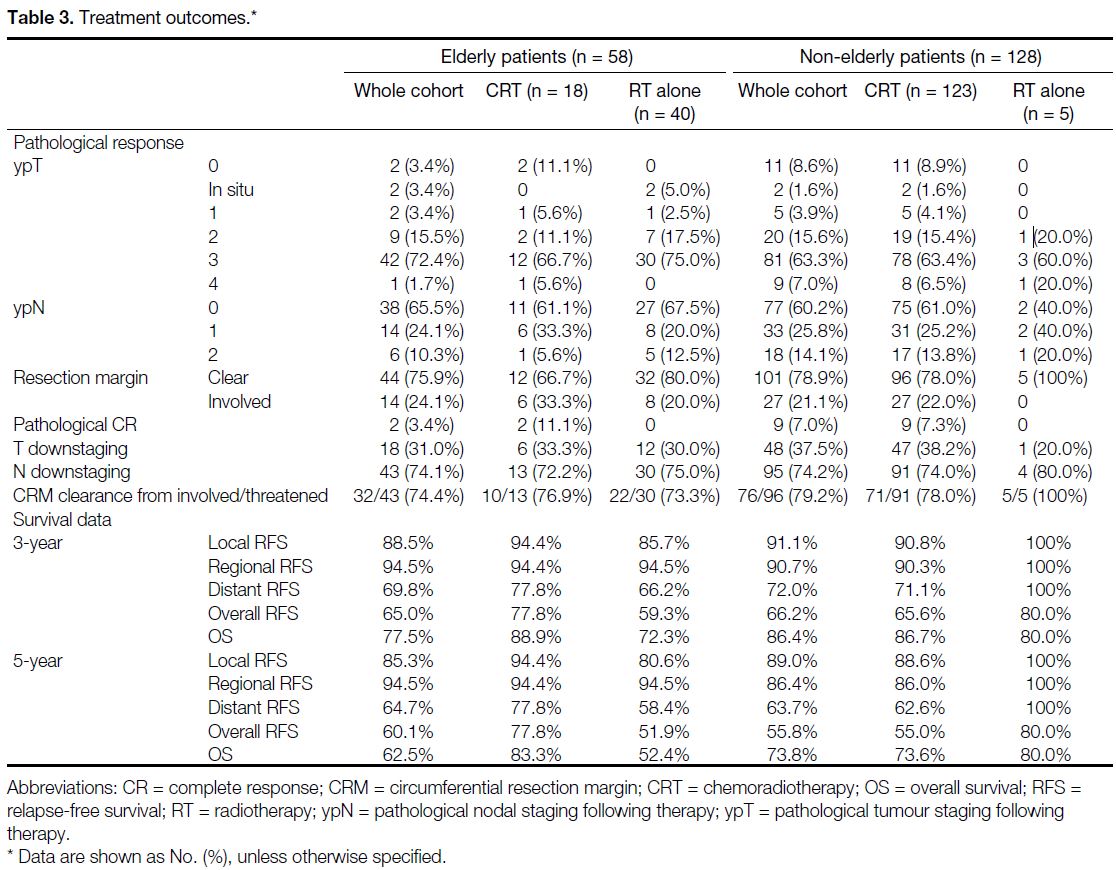

No statistically significant difference in treatment

outcomes was observed between elderly and non-elderly

cases, or between the CRT and RT-alone arms. Eleven

patients achieved a pathological complete response after

neoadjuvant treatment, with all of them had received

neoadjuvant CRT; the incidence was similar in the

elderly and non-elderly CRT cohorts. Detailed treatment

outcomes are listed in Table 3.

Table 3. Treatment outcomes.

The 5-year local RFS, regional RFS, distant RFS,

overall RFS and OS of the entire cohort were 88.0%,

88.7%, 63.9%, 57.1% and 70.2%, respectively. Elderly

and non-elderly patients who underwent CRT did not

demonstrate a statistically significant difference in any

survival endpoints. Five patients in the elderly RT-alone

subgroup died of non-cancer causes (12.5% of the

subgroup; 3 due to infection, 1 due to acute myocardial

infarction, and 1 due to cerebrovascular accident); no

non-cancer mortality was documented in the elderly

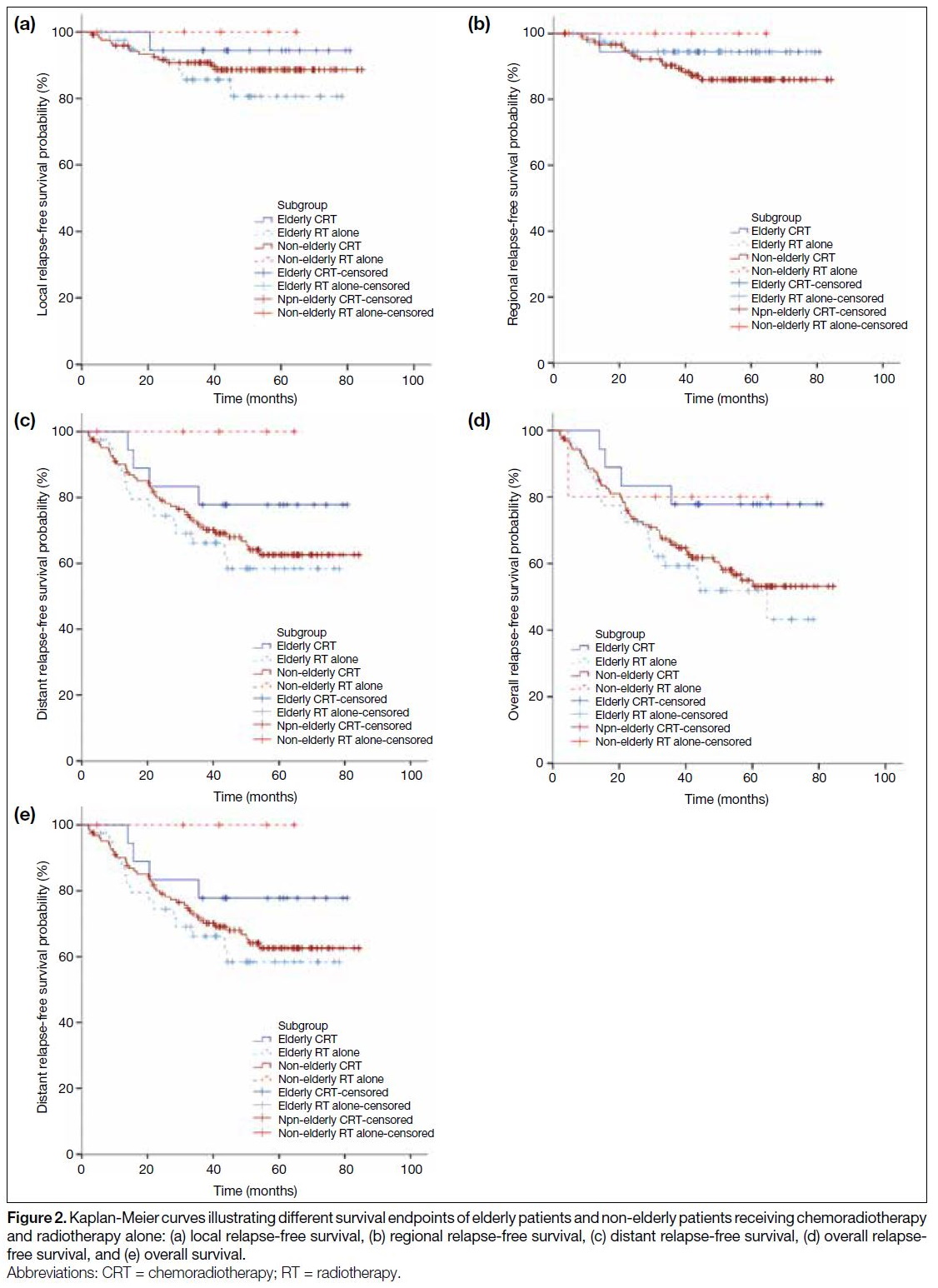

CRT subgroup. The Kaplan-Meier curves of the survival

endpoints are demonstrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Kaplan-Meier curves illustrating different survival endpoints of elderly patients and non-elderly patients receiving chemoradiotherapy

and radiotherapy alone: (a) local relapse-free survival, (b) regional relapse-free survival, (c) distant relapse-free survival, (d) overall relapse-free survival, and (e) overall survival.

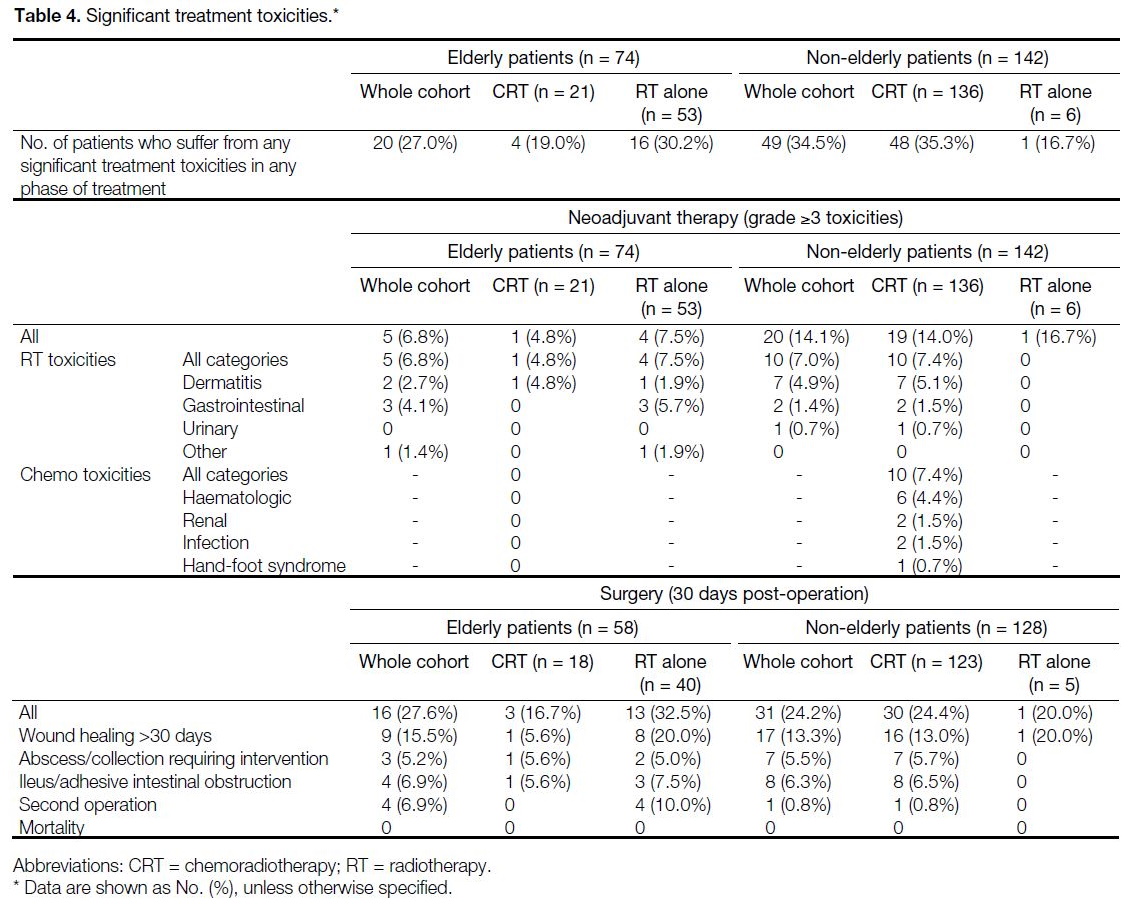

Elderly patients who underwent neoadjuvant CRT

had noninferior toxicities and safety profiles in both

neoadjuvant treatment and surgery when compared to

their non-elderly counterparts. The incidence of grade ≥3

toxicities in neoadjuvant treatment in elderly and non-elderly

CRT arms were 4.8% and 14.0%, respectively.

Postoperative 30-day morbidities were 16.7% and

24.4%, respectively. Elderly patients who underwent

neoadjuvant RT alone had higher incidence of significant

treatment toxicities, with 7.5% having grade ≥3 RT

toxicities, and 32.5% having significant morbidities after

operation. No treatment-induced mortality was observed in this cohort. Table 4 shows the incidence of significant treatment toxicities.

Table 4. Significant treatment toxicities.

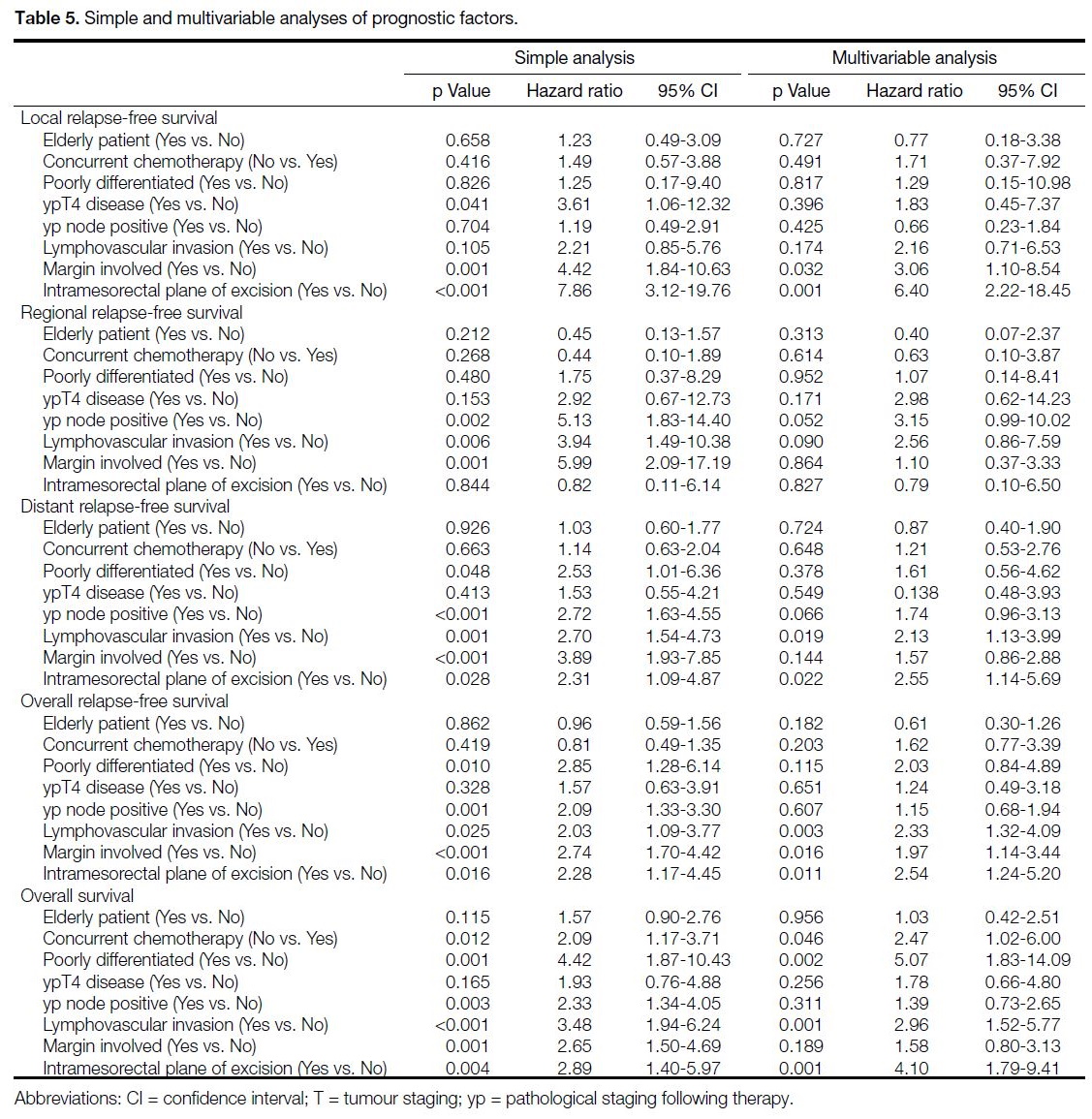

Analyses of prognostic factors indicated that older

age was not a significant prognostic factor in any of

the categories of survival on simple and multivariable

analyses. After multivariable regression analysis,

resection margin involvement and intramesorectal plane

of excision were significantly associated with shorter

local RFS. Presence of lymphovascular invasion and

intramesorectal plane of excision were significantly

associated with shorter distant RFS. Lymphovascular

invasion, margin involved, and intramesorectal plane

of excision were significantly associated with shorter

overall RFS. Absence of concurrent chemotherapy,

poorly differentiated histology, lymphovascular

invasion, and intramesorectal plane of excision were

significantly associated with shorter OS. The simple and

multivariable analyses results are shown in Table 5.

Table 5. Simple and multivariable analyses of prognostic factors.

DISCUSSION

Elderly rectal cancer patients were a heterogenous group

with diverse outcomes after neoadjuvant treatment, as

demonstrated by our study, which is to date the largest

reported Hong Kong cohort, and with neoadjuvant

CRT outcomes comparable to local and international

data.[2] [10] [11] [12]

Elderly patients deemed fit for neoadjuvant CRT

had comparable outcomes compared to their non-elderly

counterparts, including pathological complete

response rate, rate of tumour downstaging, probability

of conversion from involved/threatened CRM,

survival endpoints, and adverse events. On simple

and multivariable analyses, it was demonstrated that

old age was not an independent prognostic factor in

any categories of survival. This echoes the findings of

Kang et al,[7] demonstrating an elderly subgroup treated

with trimodality therapy with survival outcomes similar

to those of younger patients.

Whereas less fit patients in this study underwent

neoadjuvant RT alone, they tolerated the whole treatment

course less well, despite treatment de-escalation, with

30.2% experiencing significant treatment toxicities, and

17.0% not completing treatment due to frailty and non-compliance.

A total of five out of 40 patients (12.5% of

the subgroup) that completed treatment died due to non-cancer

causes. Our RT-alone cohort — mostly elderly

patients — had poorer OS, which was in contrast to

published data that suggested concurrent chemotherapy

omission was not detrimental to RFS or OS.[3] [13] The

reason behind poorer OS in our RT-alone cohort was

likely due to selection bias, as the patients were of more

advanced age, with more comorbidities and a higher

incidence of non-cancer mortalities, with limited choices

for palliative systemic treatment of disease recurrence.

In our institution, patients’ fitness for treatment

was assessed based on ECOG PS score, age, and

comorbidities. Inter-observer variability is inevitable, and discrepancies between physiological and

chronological ages exist. Despite multidisciplinary team

meeting endorsement, the treatments for a portion of less

fit patients were futile on retrospective review, ranging

from incapability to tolerate the whole treatment course

to short lifespan after treatment completion. There is

therefore a need for more accurate and objective tools

to stratify patients’ fitness for different intensities of

neoadjuvant treatments, or even radical treatment at all.

Multidisciplinary participation in comprehensive

geriatric assessment is recommended by the International

Society of Geriatric Oncology when assessing frailty

for tailoring the treatment plan in colorectal cancers.[14]

However, it is a time- and resource-consuming process

which hinders its routine use. Specific to rectal cancer,

an international expert panel recommends patients aged

≥70 years to receive mandatory office-based frailty

screening tests before being considered for usual care[15]; any presence of a frailty predictor requires a formal

geriatric assessment and a geriatrician’s presence in

multidisciplinary decision making.

After careful assessment of fitness and frailty, treatment

intent and its intensity should be adjusted accordingly. A

review by Wang et al[16] proposed a treatment algorithm

for locally advanced rectal cancer in elderly/comorbid

patients based on degree of frailty. Elderly patients

that are fully fit should undergo neoadjuvant treatment,

either long-course CRT or short-course RT alone, before

radical surgery. For less fit patients, different emerging

nonsurgical treatment approaches, e.g., watch and wait

approach or brachytherapy boost after CRT, should be

considered. Palliative RT, or even symptomatic care,

should be considered if patients are deemed frail. The

adaptation of the abovementioned approaches will likely

screen out unfit patients, avoid futile treatments in patients

with limited life expectancies due to comorbidities, and minimise unbearable treatment toxicities.

Besides fitness for treatment, elderly patients’ goals

and preferences in treatment outcomes should be

carefully respected during treatment planning. In our

study, 9.4% of the elderly patients subsequently refused

radical surgery after receiving neoadjuvant treatment.

The specific reasons of treatment refusal were not

documented in clinical notes, yet potential reasons

may be due to fear of surgical/anaesthetic risk, or the

subsequent inconvenience with a temporary/permanent

stoma. Thorough counselling, before and during treatment, would be helpful to formulate a tailor-made

treatment plan in respect of patients’ preferences, and

ensure compliance with treatment.

The concept of total neoadjuvant therapy for rectal

cancers was introduced in recent years, with two phase

III trials showing that such approach provided a superior

pathological complete response rate and outcomes at 3

years (3-year disease-free survival in the UNICANCER-PRODIGE

23 trial, disease-related treatment failure at

3 years in the RAPIDO trial).[17] [18] Although OS data were

immature to demonstrate superiority of total neoadjuvant therapy,[19] adding neoadjuvant chemotherapy is being

increasingly adopted as a treatment option worldwide.

This approach, however, will lead to more systemic

chemotherapy exposure and may pose extra toxicities

to patients. He et al[20] reported that the addition of

neoadjuvant chemotherapy to neoadjuvant CRT in the

elderly patients gave rise to similar disease-related survival

rates and oncological outcomes with that of younger

patients, but geriatric assessments and complications

data were lacking in the study. It is expected that as we

intensify the magnitude of our neoadjuvant treatment,

there will be a growing importance in proper patient

selection to balance the risk and benefits of treatment.

There were limitations to this study. The study data was

collected retrospectively, limiting the completeness of

data and introducing potential bias during data collection.

There was selection bias during referral and initiation of

neoadjuvant treatment, thus epidemiological data were

limited. There was also selection bias when patients

were assigned to different neoadjuvant treatment arms

(i.e., with or without concurrent chemotherapy), thus

confounding factors that were not identified in this

study may be present. A short-course RT scheme was

not adopted in this cohort, limiting our scope of analysis

and subsequent recommendations. Absence of detailed

parameters of elderly patients’ conditions and the small

sample size of this study limit the ability to identify

prognostic factors to predict tolerance to treatment, and

to derive further recommendations.

CONCLUSION

Age alone should not be a deterministic factor in treatment intensity consideration in locally advanced rectal cancer.

Satisfactory oncological outcomes can be achieved

in selected elderly patients with locally advanced

rectal cancers who undergo standard neoadjuvant

treatment and radical surgery, while the risk of shorter

survival and toxicities is higher in less fit candidates.

Utilisation of geriatric screening and assessment tools,

and consideration of patients’ preference and treatment

objectives are required to achieve tailor-made treatment

schemes and optimise treatment outcomes.

REFERENCES

1. Hong Kong Cancer Registry. Overview of Hong Kong Cancer

Statistics of 2019. October 2021. Available from: https://www3.ha.org.hk/cancereg/pdf/overview/Overview%20of%20HK%20Cancer%20Stat%202019.pdf

. Accessed 17 Apr 2022.

2. Sauer R, Becker H, Hohenberger W, Rödel C, Wittekind C, Fietkau R, et al. Preoperative versus postoperative chemoradiotherapy for rectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1731-40. Crossref

3. De Caluwé L, Van Nieuwenhove Y, Ceelen WP. Preoperative

chemoradiation versus radiation alone for stage II and III resectable

rectal cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(2):CD006041. Crossref

4. Glynne-Jones R, Wyrwicz L, Tiret E, Brown G, Rödel C, Cervantes A, et al. Rectal cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice

Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2017;29(Suppl 4):iv22-40. Crossref

5. Benson AB, Venook AP, Al-Hawary MM, Azad N, Chen YJ, Ciombor KK, et al. Rectal cancer, version 2.2022, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw.

2022;20:1139-67. Crossref

6. Choi Y, Kim JH, Kim JW, Kim JW, Lee KW, Oh HK, et al. Preoperative chemoradiotherapy for elderly patients with locally advanced rectal cancer — a real-world outcome study. Jpn J Clin

Oncol. 2016;46:1108-17. Crossref

7. Kang S, Wilkinson KJ, Brungs D, Chua W, Ng W, Chen J, et al. Rectal cancer treatment and outcomes in elderly patients treated with curative intent. Mol Clin Oncol. 2021;15:256. Crossref

8. Mourad AP, De Robles MS, Putnis S, Winn RD. Current treatment approaches and outcomes in the management of rectal cancer above the age of 80. Curr Oncol. 2021;28:1388-401. Crossref

9. Tominaga T, Nagasaki T, Akiyoshi T, Fukunaga Y, Fujimoto Y, Yamaguchi T, et al. Feasibility of neoadjuvant therapy for elderly patients with locally advanced rectal cancer. Surg Today. 2019;49:694-703. Crossref

10. Lee SF, Chiang CL, Lee FA, Wong YW, Poon CM, Wong FC, et al.

Outcome of neoadjuvant chemoradiation in MRI staged locally

advanced rectal cancer: retrospective analysis of 123 Chinese

patients. J Formos Med Assoc. 2018;117:825-32. Crossref

11. Yeung WW, Ma BB, Lee JF, Ng SS, Cheung MH, Ho WM, et al.

Clinical outcome of neoadjuvant chemoradiation in locally

advanced rectal cancer at a tertiary hospital. Hong Kong Med J.

2016;22:546-55. Crossref

12. Sauer R, Liersch T, Merkel S, Fietkau R, Hohenberger W, Hess C,

et al. Preoperative versus postoperative chemoradiotherapy for

locally advanced rectal cancer: results of the German CAO/ARO/AIO-94 randomized phase III trial after a median follow-up of 11

years. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1926-33. Crossref

13. Bosset JF, Collette L, Calais G, Mineur L, Maingon P, Radosevic-Jelic L, et al. Chemotherapy with preoperative radiotherapy in rectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1114-23. Crossref

14. Papamichael D, Audisio RA, Glimelius B, de Gramont A, Glynne-Jones R, Haller D, et al. Treatment of colorectal cancer in older patients: International Society of Geriatric Oncology (SIOG) consensus recommendations 2013. Ann Oncol. 2015;26:463-76. Crossref

15. Montroni I, Ugolini G, Saur NM, Spinelli A, Rostoft S, Millan M,

et al. Personalized management of elderly patients with rectal

cancer: Expert recommendations of the European Society

of Surgical Oncology, European Society of Coloproctology,

International Society of Geriatric Oncology, and American

College of Surgeons Commission on Cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol.

2018;44:1685-702 Crossref

16. Wang SJ, Hathout L, Malhotra U, Maloney-Patel N, Kilic S, Poplin E, et al. Decision-making strategy for rectal cancer management using radiation therapy for elderly or comorbid

patients. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2018;100:926-44. Crossref

17. Conroy T, Bosset JF, Etienne PL, Rio E, François É, Mesgouez-Nebout N, et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy with FOLFIRINOX and preoperative chemoradiotherapy for patients with locally

advanced rectal cancer (UNICANCER-PRODIGE 23): a

multicentre, randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol.

2021;22:702-15. Crossref

18. Bahadoer RR, Dijkstra EA, van Etten B, Marijnen CA, Putter H, Kranenbarg EM, et al. Short-course radiotherapy followed by chemotherapy before total mesorectal excision (TME) versus

preoperative chemoradiotherapy, TME, and optional adjuvant

chemotherapy in locally advanced rectal cancer (RAPIDO): a

randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22:29-42. Crossref

19. Kasi A, Abbasi S, Handa S, Al-Rajabi R, Saeed A, Baranda J, et al. Total neoadjuvant therapy vs standard therapy in locally advanced rectal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e2030097. Crossref

20. He F, Chen M, Xiao WW, Zhang Q, Liu Y, Zheng J, et al. Oncologic

and survival outcomes in elderly patients with locally advanced

rectal cancer receiving neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy and total

mesorectal excision. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2021;51:1391-9. Crossref