Acute Leukaemia of Ambiguous Lineage Presenting as a Focal Bone Lesion: a Case Report

CASE REPORT

Acute Leukaemia of Ambiguous Lineage Presenting as a Focal Bone Lesion: a Case Report

H Yi1, M Dhamija2, H Dholaria3, R Kotecha2, D Roebuck3

1 Division of Paediatrics, Medical School, University of Western Australia, Australia

2 Department of Haematology and Oncology, Perth Children’s Hospital, Australia

3 Department of Medical Imaging, Perth Children’s Hospital, Australia

Correspondence: Prof. D Roebuck. Department of Medical Imaging, Perth Children’s Hospital, Australia. Email: derek.roebuck@health.wa.gov.au

Submitted: 9 Oct 2020; Accepted: 19 Jan 2021.

Contributors: HY and DR designed the study. All authors acquired the data. All authors analysed the data. HY and DR drafted the manuscript.

All authors critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study,

approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Funding/Support: This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data Availability: All data generated or analysed during the present study are included in this published article.

Ethics Approval: The study was approved by the institutional Research Ethics Committee (Ref 1769/EP).

INTRODUCTION

Acute leukaemia is the most common childhood

malignancy. Almost all cases are classified as acute

lymphoblastic leukaemia (ALL) or acute myeloid

leukaemia (AML). Acute leukaemia of ambiguous

lineage (ALAL) is a rare form of acute leukaemia that

cannot be classified by a single lineage.[1] Like other acute

leukaemias, ALAL typically presents with nonspecific

symptoms such as fatigue, fever, or bleeding.[2] Although

presentation with musculoskeletal symptoms such as

bone pain is not uncommon in acute leukaemia, a focal

pattern of bone involvement at presentation is rarely

observed and has not been described in children with

ALAL. We describe the case of a 16-month-old girl

with ALAL who presented with a focal destructive bone

lesion.

CASE REPORT

A 16-month-old girl was referred to our oncology unit with a 3-week history of progressive pain, irritability

and inability to bear weight on her left lower limb. She was a twin born at 34 weeks’ gestation from an in vitro

fertilisation pregnancy and was well prior to presentation.

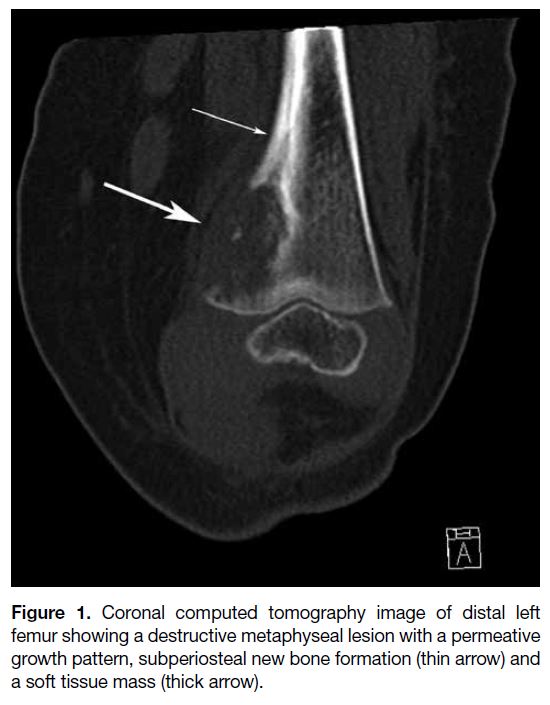

A radiograph of the left femur (not shown) revealed a permeative lytic lesion in the left distal femoral

metaphysis. Lower limb computed tomography (CT)

showed a destructive lesion, with a small soft tissue

mass, suggestive of a primary bone tumour, Langerhans

cell histiocytosis, or a metastasis (Figure 1). Magnetic

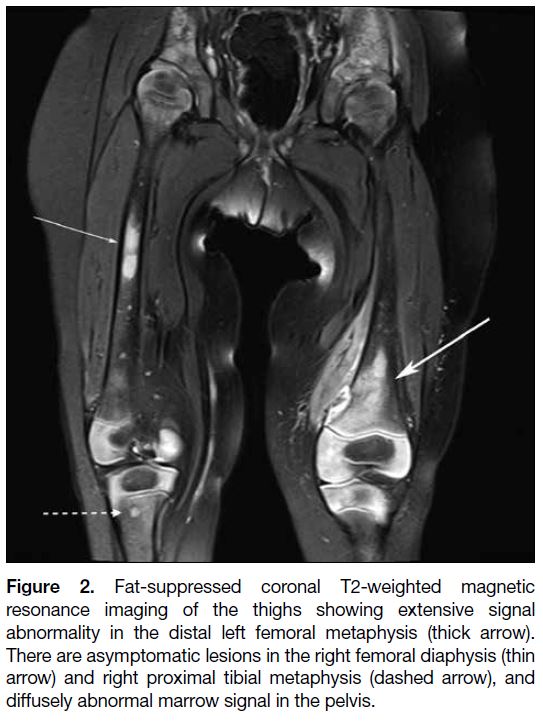

resonance imaging (MRI) of the thighs showed

numerous other focal bone lesions, all asymptomatic

(Figure 2), and CT of the chest and abdomen showed no

evidence of lymph node enlargement, organomegaly or

soft tissue mass. Initial blood investigations and urinary

catecholamines were normal. The femoral lesion was

biopsied, revealing a largely necrotic undifferentiated

neoplasm with focal areas of viable tissue and large

round blue cells. The viable cells were positive for

CD99, CD43, CD34, CD117, vimentin and CD56, and

negative for lymphoid and other solid tumour markers

on immunohistochemical staining.

Figure 1. Coronal computed tomography image of distal left

femur showing a destructive metaphyseal lesion with a permeative

growth pattern, subperiosteal new bone formation (thin arrow) and

a soft tissue mass (thick arrow).

Figure 2. Fat-suppressed coronal T2-weighted magnetic

resonance imaging of the thighs showing extensive signal

abnormality in the distal left femoral metaphysis (thick arrow).

There are asymptomatic lesions in the right femoral diaphysis (thin

arrow) and right proximal tibial metaphysis (dashed arrow), and

diffusely abnormal marrow signal in the pelvis.

During her diagnostic workup, she developed

left-sided facial weakness with drooling. MRI

demonstrated extensive calvarial marrow infiltration,

with compression of the facial nerve by a left mastoid

lesion, and extensive vertebral infiltration with

pathological fractures. Cerebrospinal fluid examination

was negative for malignant cells. Positron emission

tomography–computed tomography (PET-CT) with

18F-fluorodeoxyglucose revealed diffuse skeletal

and splenic uptake. She was started on emergency

chemotherapy with carboplatin and etoposide while

awaiting confirmation of the final diagnosis.

The bone marrow aspirates and trephines revealed up to 20% blasts, with immunohistochemical staining

showing the same characteristics as the bone biopsy.

Cytogenetic assessment of the bone marrow aspirates

revealed a 46,XX,der(7)t(7;16)(q36;p11.2),der(8)t(1;8)

(q25;p23),der(16)inv(16)(p11.2q24)t(7;16)(q36;p11.2)

[9]/46,XX[11] karyotype consistent with a neoplastic

clone. Bone biopsies from her left iliac wing and tibia

showed significant blast infiltration, strongly positive for

CD33, CD34, CD117, CD16/56 and cytoplasmic CD3,

but negative for cytoplasmic myeloperoxidase, HLA-DR,

nuclear TDT, other B/T-cell markers (including

CD7), and monocyte antigens.

Given these findings, a final diagnosis of ALAL was made, with features of AML and early T-cell precursor

ALL. Given the predominance of myeloid markers, she

was started on AML therapy according to the high-risk

arm of the Children’s Oncology Group AAML1031 study.

She demonstrated significant clinical improvement with this treatment, and bone marrow aspirates and trephines

following the first cycle of definitive therapy revealed

complete morphological and cytogenetic remission, with

a very good partial response on PET-CT and brain MRI.

At the end of treatment, following four cycles of therapy,

she was in morphological, cytogenetic and radiological

remission, but within a month of treatment completion

she presented with pneumonia and left hip joint pain.

MRI revealed multifocal areas of marrow infiltrate in

the lumbar spine, pelvis, and proximal femora, with

diffuse skeletal fluorodeoxyglucose avidity on PET-CT.

An aspirate of a left hip joint effusion was consistent

with disease relapse. An attempt was made to induce

remission using T-cell ALL–based therapy, but she

deteriorated rapidly and died of progressive disease.

DISCUSSION

The World Health Organization has recently updated its classification of ALAL after changes to its definition

over the years.[1] ALAL is uncommon in children and is

particularly rare in infancy. Its exact incidence is difficult

to establish because of changes in definitions over the

years, but accounts for approximately 3% of paediatric

leukaemias.[2] There are no series specifically reporting

the clinical features of ALAL, but it has been stated

that fatigue, infections, and bleeding manifestations

are common presentations.[2] Central nervous system

involvement at the time of diagnosis has been reported

in about 20% of children, significantly more often than

in ALL.[3] [4]

Children with ALL typically present with fever,

bleeding, pallor, fatigue, rash, lymphadenopathy

or organomegaly.[5] Bone involvement occurs at

presentation in about one quarter of patients and

radiological investigations usually reveal a diffuse

pattern of bone change such as osteopenia or radiolucent

metaphyseal bands, rather than one or more focal

masses.[6] AML shares many of the clinical features of

ALL. Other common manifestations of AML include

gingival infiltration and leukaemia cutis.[5] Nonetheless

bone involvement in paediatric AML is uncommon

compared with ALL. Reports of focal bone lesions are

sparse in ALL or AML, and this presentation has not been

reported in children with ALAL. Ghodke et al[7] described

an 8-year-old female who presented with swelling of her

right cheek without other symptoms. Imaging revealed

a solitary soft tissue mass in the right maxillary sinus

and erosion of the alveolar process. Blood, bone marrow

and cerebrospinal fluid examination were all normal.

Immunophenotyping of a biopsy revealed both myeloid

and lymphoid commitment, and a diagnosis of bi/mixed

phenotypic blastic haematolymphoid neoplasm was

made, as bone marrow was not involved.[7]

Our patient presented with pain, irritability and

difficulty weight-bearing. CT showed a focal aggressive

metaphyseal lesion. In contrast to most patients with

ALL and AML, no systemic features were present at presentation and blood tests were essentially normal. Early

diagnosis of ALAL can therefore be very challenging

with this type of presentation. The differential diagnosis

of a focal destructive bone lesion in younger children

includes infection, Ewing sarcoma, metastasis (especially

from neuroblastoma), and Langerhans cell histiocytosis,

in addition to haematological malignancies. Because

early diagnosis and treatment of acute leukaemia reduces

morbidity and mortality,[8] a high degree of suspicion

should be maintained in a child who presents with bone

lesions.

In summary, ALAL is a rare form of acute leukaemia that can present with focal bone lesions in children. Our

patient demonstrated the radiographic challenges in

making an early diagnosis of acute leukaemia and serves

as a reminder that this diagnosis should be considered in

all children with destructive bone lesions.

REFERENCES

1. Arber DA, Orazi A, Hasserjian R, Thiele J, Borowitz MJ,

Le Beau MM, et al. The 2016 revision to the World Health

Organization classification of myeloid neoplasms and acute

leukemia. Blood. 2016;127:2391-405. Crossref

2. Duffield AS, Weir EG, Borowitz MJ. Acute leukemias of

ambiguous lineage. In: Jaffe ES, Arber DA, Campo E, Harris NL,

Quintanilla-Martinez L, editors. Hematopathology. Philadelphia

(PA): Elsevier; 2017. p 775-82.

3. Gerr H, Zimmermann M, Schrappe M, Dworzak M, Ludwig WD, Bradtke J, et al. Acute leukaemias of ambiguous lineage in children: characterization, prognosis and therapy recommendations. Br J Haematol. 2010;149:84-92. Crossref

4. Hrusak O, de Haas V, Stancikova J, Vakrmanova B, Janotova I,

Mejstrikova E, et al. International cooperative study identifies

treatment strategy in childhood ambiguous lineage leukemia. Blood

2018;132:264-76. Crossref

5. Lanzkowsky P, Lipton JM, Fish JD, editors. Lanzkowsky’s Manual of Pediatric Hematology and Oncology. Boston (MA): Elsevier; 2016.

6. Sinigaglia R, Gigante C, Bisinella G, Varotto S, Zanesco L, Turra S.

Musculoskeletal manifestations in pediatric acute leukemia. J

Pediatr Orthop. 2008;28:20-8. Crossref

7. Ghodke K, Tembhare P, Patkar N, Subramanian PG, Arora B, Gujral S. A rare extramedullary and extralymphoid presentation of mixed phenotypic blastic hematolymphoid neoplasm: a study

of two cases. Indian J Med Paediatr Oncol. 2017;38:394-7. Crossref

8. Dang-Tan T, Franco EL. Diagnosis delays in childhood cancer: a review. Cancer. 2007;110:703-13. Crossref