Challenges in Initiating a Cerebral Aneurysm Coiling Programme in a Small Centre: Our Experience after the First 100 Cases

PERSPECTIVE

Challenges in Initiating a Cerebral Aneurysm Coiling Programme in a Small Centre: Our Experience after the First 100 Cases

C Woodworth1, V Linehan2, N Hache1, R Bhatia1, P Bartlett1

1 Discipline of Radiology, Faculty of Medicine, Memorial University of Newfoundland, Canada

2 Department of Diagnostic Radiology, Faculty of Medicine, Dalhousie University, Canada

Correspondence: Dr V Linehan, Department of Diagnostic Radiology, Faculty of Medicine, Dalhousie University, Canada. Email: victoria.linehan@dal.ca

Submitted: 27 Mar 2021; Accepted: 17 Jun 2021.

Contributors: CW, NH, RB and PB designed the study. CW and VL acquired and analysed the data. All authors drafted the manuscript and critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Funding/Support: This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data Availability: All data generated or analysed during the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: To verify the quality of our newly implemented neurointerventional programme, we obtained local ethics approval to initiate a retrospective review of all patients who underwent cerebral coiling from March 2013 until December 2017.

Abstract

After completing the 100th intracranial aneurysm coiling at our site in 2017, we reflect on the challenges of

implementing a new neurointerventional radiology programme in a small tertiary care centre. Our radiology group

is the sole provider of cerebral coiling for a population of approximately 500,000, first offering this procedure in

March 2013. Given the challenges that we encountered while establishing this programme, we wish to share lessons

learned about resource advocacy, early involvement of key stakeholders, and timely programme introduction to help

others facing similar needs.

Key Words: Aneurysm, ruptured; Embolization, therapeutic; Intracranial aneurysm; Radiology

中文摘要

在小型醫療中心開始腦動脈彈簧圈栓塞術面臨的挑戰:最初100例後我們的經驗

C Woodworth、V Linehan、N Hache、R Bhatia、P Bartlett

2017年在我們的醫院完成第100例顱內動脈瘤彈簧圈栓塞手術後,我們回顧在小型三級醫療中心實施新的神經介入放射學計劃所面臨的挑戰。於2013年3月首次開始,我們的放射科是為大約500,000人口提供顱內動脈彈簧圈栓塞手術的唯一醫療機構。鑑於我們在建立該計劃時遇到的挑戰,我們希望分享有關爭取資源、早期溝通相關人士、並及時把我們的計劃介紹給面臨類似需求機構的經驗。

BACKGROUND

Most commonly found at arterial bifurcations in the circle of Willis, intracranial aneurysms have a prevalence of

2% to 3%.[1] Rupture causes subarachnoid haemorrhage,

which is associated with severe neurological impairment

and a 30% to 40% fatality rate.[2] Prompt treatment of

ruptured intracranial aneurysms by surgical clipping or

endovascular coiling reduces morbidity and mortality by

decreasing rebleeding and vasospasm.[3] [4]

The first patient was treated with endovascular therapy in 1990,[5] with the United States Food and Drug

Administration approval of the Guglielmi detachable

coil in 1995. Endovascular coiling became the preferred

treatment in 2002 when the International Subarachnoid

Aneurysm Trial showed a significant benefit of

endovascular treatment, with a 23.9% reduction in the

relative risk of death or disability at 1 year compared to

surgical clipping.[6]

Despite becoming one of the standard treatments for

ruptured cerebral aneurysms, this interventional service

is not uniformly available. Before a cerebral coiling

service was established at the Health Sciences Centre,

a small tertiary centre in the Canadian province of

Newfoundland, all ruptured aneurysms from within

the local population of 500,000 had to be transferred

to a larger centre in the neighbouring province of Nova

Scotia (1.5 hours by air) for endovascular treatment. In

2003, our Chief of Neurosurgery wrote a formal letter to

our radiology department stating that it was ‘imperative’

that endovascular coiling of intracranial aneurysms ‘be

started as soon as possible at our institution’ to reduce

unnecessary treatment delays. Therefore, we began the

daunting task of implementing a new neurointerventional

service at our centre that would be permanently available

around the clock.

Our Approach to Implementation

There are numerous factors to consider when

implementing a new service, including costs, resource

advocacy, specialised training, involvement of key

stakeholders, and patient safety. Local administrative

systems and funding should be considered from the

onset. Our local healthcare system is publicly financed

with revenue from federal, provincial, and territorial

taxation. The Medical Care Plan is a comprehensive

provincial insurance that covers the cost of physician

services for patients, including hospital services.

Physicians receive compensation by negotiating fee

codes and billing Medical Care Plan for insured hospital services when recommended by a medical practitioner.

Different specialists require separate fee codes for each

procedure. New hospital services are approved by the

Regional Health Authority Executive Team. Hospital

departments have separate operating budgets, meaning

that funding for a new neurointerventional radiology

programme would largely need to come from our own

budget. Unfortunately, we encountered many challenges

that introduced significant delays that wasted time,

resources, finances, and training.

Costs

We first considered the cost of implementing a new

service, notably the significant upfront costs to develop

the necessary infrastructure for neurointerventional

procedures. We would need a new biplane angiography

suite (US$2,024,000), a secondary multipurpose

angiography suite for displaced cases (US$748,000),

an inventory of coils and guidewires (US$352,000),

departmental renovations (US$440,000), and salary for

two additional nurses and one technologist.

We estimated that the cost-per-case would be lower if

the service were performed at our centre, as we would

avoid the costs of air transport (US$9303). However, we

recognised that this was not necessarily a money-saving

initiative. Our centre would reallocate the neurosurgery

aneurysm clipping operating room time with other

costly surgeries and available beds would be filled with

other patients. Rather, the major benefit would be not

transferring critically ill patients via air ambulance.

Resource Advocacy

With the support of the Department of Neurosurgery, we approached our hospital’s Vice President of Medicine to

request the necessary resources. There were numerous

meetings in which we emphasised that deferred

implementation of a coiling programme would result in

substandard care. In 2006, our health authority requested

US$3,564,000 in capital governmental funds to meet the

upfront costs for programme implementation. Likely

because of our partnership with the Department of

Neurosurgery (those responsible for managing patient

treatment plans and referrals to our services) and the

recognition that this programme was necessary to meet

the standard of care, a new biplane angiography suite

was quickly approved and installed early in 2008.

Specialised Training

To prepare for programme implementation, we

considered radiologist education. Two of our three interventional neuroradiologists had standard fellowship

training at accredited Canadian institutions, which they

finished in 2001 and 2005. Their fellowship training

included intracranial aneurysm coiling techniques.

The third and most senior neuroradiologist completed

a cerebral coiling sabbatical in early 2008 in tandem

with the installation of the biplane angiography suite.

With 30 cases predicted yearly, our service would have

a sufficient critical volume to maintain cerebral coiling

expertise.

Unexpected Delays due to Late Involvement

of Key Stakeholders

We were hopeful that we could begin coiling in the fall of 2008; however, we encountered further obstacles.

Although casual conversations were conducted, we

erred in not formally involving the Department of

Anaesthesiology from the onset. Getting available

anaesthesiologists was an obstacle, as the angiography

suite was a new location for them to cover. Issues around

fee codes had to be overcome, because the Departments

of Radiology and Anaesthesiology each required

separate fee codes for this new procedure to receive

compensation. Furthermore, given the unscheduled and

urgent nature of many coiling cases, additional overtime

coverage was needed.

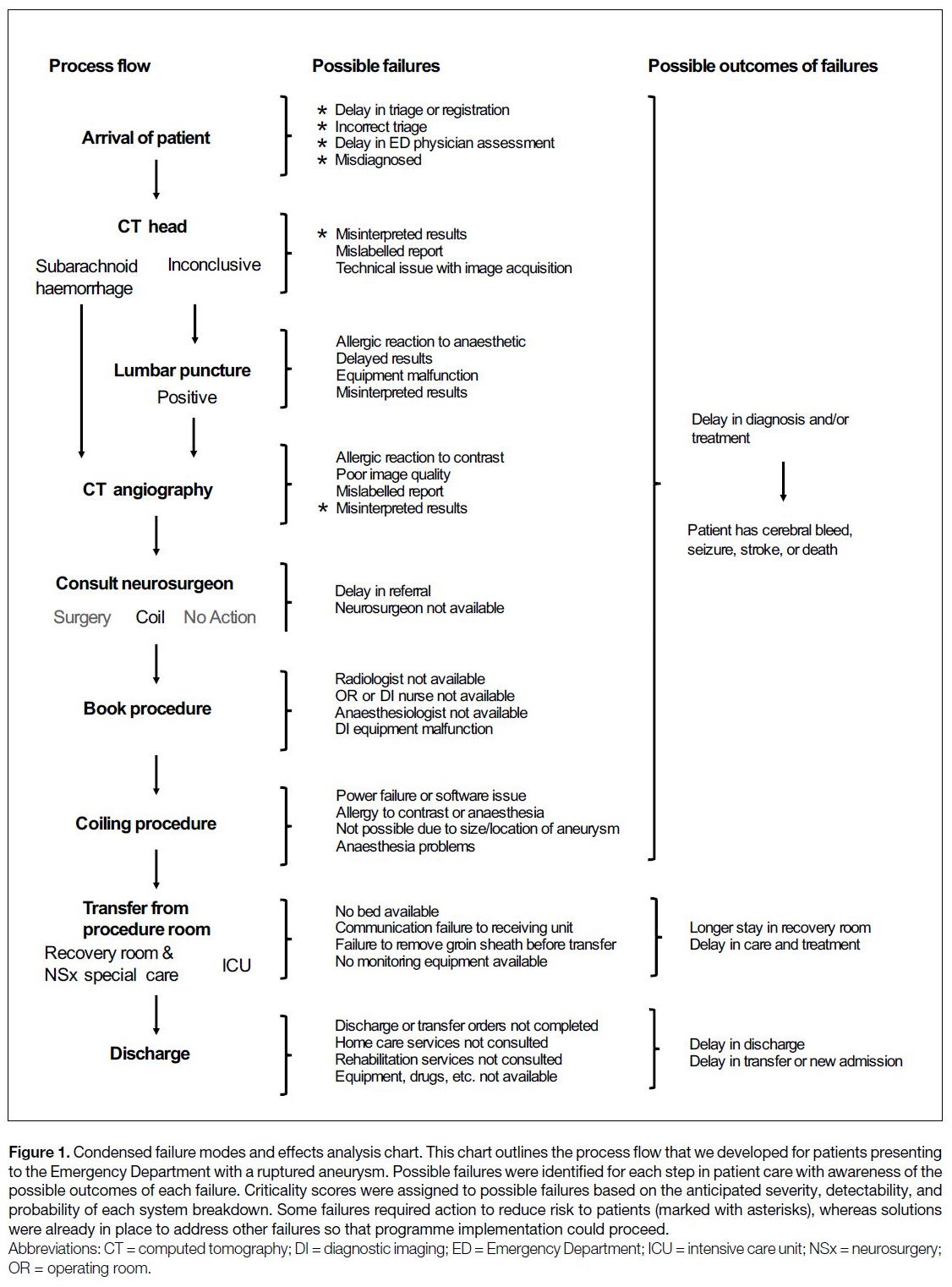

Just before implementation of the programme, we were

required to complete a failure modes and effects analysis

(FMEA), which is a systematic method of identifying

where and how issues might arise (Figure 1). This

process evaluated all anticipated failures at every step of

patient treatment, from initial examination to discharge

from the hospital after surgery, to calculate patient risk

in all potential scenarios. Our quality assurance team

ranked the severity, detectability, and probability of

potential failures on a scale from 1 to 5 and calculated

the criticality score from the product of these scores. An

unacceptable risk to patients was defined as a score of 5

for severity or a criticality score of >20. An unacceptable

risk score stalled the FMEA and required intervention

by the quality assurance team to adjust procedures and

policies or to provide additional training of staff that may

be involved in the process flow to reduce risks to patients

(Figure 1). After the intervention, the criticality score

was recalculated, and this process was continued until all

potential failures were assigned acceptable severity ranks

and criticality scores to ensure that all considerations

were made. This clarified our workflow and service

model from the onset. For elective cases, neurosurgery

is responsible for initial patient assessment and referral to interventional neuroradiology for aneurysms that can

be clipped or coiled. Interventional neuroradiology will

also assess the patient, discuss the procedure with the

patient, and obtain informed consent. Elective patients

are subsequently assessed in the Outpatient Preoperative

Assessment Clinic by anaesthesiology. All specialists

work together for patient care and can raise concerns

regarding safety and the risk-benefit ratio for the patient.

Neurosurgery is responsible for management after

surgery, with the services again working collaboratively

toward patient discharge. Patients are followed clinically

by neurosurgery and follow-up imaging is completed by

radiology, typically at 3 months after surgery and once

per year thereafter. This arrangement is also followed for

emergency patients, albeit on an accelerated timeline,

with all assessments made in the hospital on an emergent

basis. FMEA enabled us to pre-emptively improve

patient safety by anticipating the logistical issues that

may arise when beginning a new service. A proctor was

present for our initial cases to aid in local programme

implementation. Credentialing was necessary for this

new procedure, which was based on the training of

the interventional neuroradiologists and the volume of

cerebral procedures needed to maintain competence.

Figure 1. Condensed failure modes and effects analysis chart. This chart outlines the process flow that we developed for patients presenting

to the Emergency Department with a ruptured aneurysm. Possible failures were identified for each step in patient care with awareness of the

possible outcomes of each failure. Criticality scores were assigned to possible failures based on the anticipated severity, detectability, and

probability of each system breakdown. Some failures required action to reduce risk to patients (marked with asterisks), whereas solutions

were already in place to address other failures so that programme implementation could proceed.

Costs of Delays

Unfortunately, FMEA is a long process: it was not until March 2013 that all recommendations and actions were

completed. We had returned the initial inventory of coils

and other supplies obtained in 2008. Restocking in 2013

caused additional expense and frustration. Moreover,

delays in programme implementation led to loss of

expertise such that the two of our three interventional

neuroradiologists required costly retraining. One of them

completed additional training over the course of 6 months

at an out-of-province high-volume centre. The other was

unable to initially participate in retraining because of

personal circumstances and is only now in the process

of retraining, which meant the programme relied on the

availability of two interventional neuroradiologists for

years. While our service is offered around the clock, in

rare contingency situations we have still have to transfer

patients by air ambulance to a larger centre depending

on the availability and expertise of the interventional

neuroradiologists.

OUTCOMES OF OUR PROGRAMME IMPLEMENTION

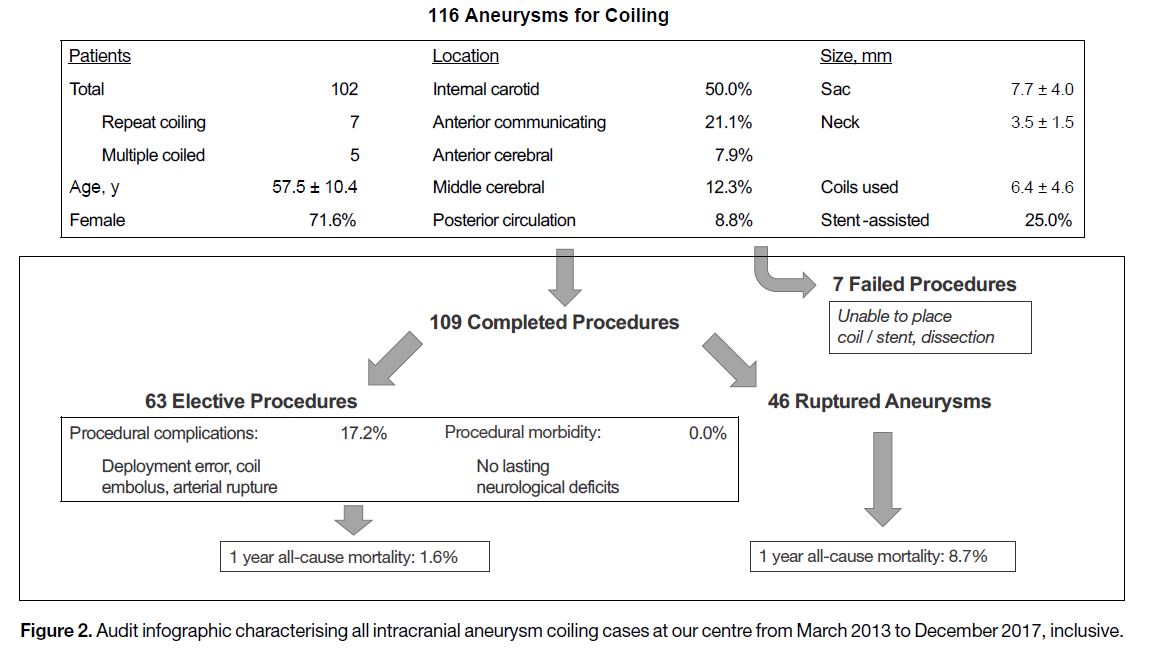

To verify the quality of our newly implemented

neurointerventional programme, we obtained local

ethics approval to initiate a retrospective review of all patients who underwent cerebral coiling from March

2013 until December 2017 (Figure 2). We found that

116 procedures were attempted on 102 patients, with

seven failures due to coil or stent placement difficulties.

Most aneurysms arose from the internal carotid artery

and over half were coiled electively. Procedural

complications encountered in the elective cases included

deployment error, coil embolisation, and arterial rupture.

As per follow-up neurosurgery examinations, there

were no lasting neurological deficits in patients treated

electively. Among those emergency cases with ruptured

aneurysms, complications were similar, although

transient thrombus formation was also frequently

documented. Patients were followed up at 3 months

after surgery and once per year thereafter with magnetic

resonance angiography to rule out recurrence. The

1-year mortality was 1.6% for elective procedures and

8.7% for ruptured aneurysm repair. This is comparable

to the literature.[7] [8] [9]

Figure 2. Audit infographic characterising all intracranial aneurysm coiling cases at our centre from March 2013 to December 2017, inclusive

CONCLUSION AND FUTURE DIRECTION

The multi-year delay in our programme’s implementation emphasises the need for early involvement of all necessary support disciplines as well as timely quality

and safety assessments. Postponing radiologist

retraining and consumable material consignment instead

of purchase may save costs. Personnel and recruitment

remain ongoing issues for our small centre given that

our programme still relies on the availability of two

interventional neuroradiologists. Other radiologists

in our group absorbed the extra workload, which

underscores the need for additional recruitment when

new services are added. We believe FMEA was integral

for anticipating patient safety concerns and ensuring a

successful programme from the onset.

Ongoing advances in interventional radiology

continually elevate the standard of care, leading to more

advanced procedures being performed at smaller centres.

This requires specialised suites with multidisciplinary

staff, presenting unique challenges to radiology groups

with limited resources and experience in programme

implementation. By outlining the various obstacles that

we faced, we hope other groups can better advocate for

and streamline the introduction of new programmes so

that they do not also experience multi-year delays. We

now find this experience particularly pertinent as we are currently evaluating whether we can offer a sustainable

endovascular thrombectomy programme for ischaemic

stroke.

REFERENCES

1. Vlak MH, Algra A, Brandenburg R, Rinkel GJ. Prevalence of

unruptured intracranial aneurysms, with emphasis on sex, age,

comorbidity, country, and time period: a systematic review and

meta-analysis. Lancet Neurol. 2011;10:626-36. Crossref

2. Nieuwkamp DJ, Setz LE, Algra A, Linn FH, de Rooij NK, Rinkel GJ. Changes in case fatality of aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage over time, according to age, sex, and region: a meta-analysis. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8:635-42. Crossref

3. Lantigua H, Ortega-Gutierrez S, Schmidt JM, Lee K, Badjatia N,

Agarwal S, et al. Subarachnoid hemorrhage: who dies, and why?

Crit Care. 2015;19:309. Crossref

4. Komotar RJ, Schmidt JM, Starke RM, Claassen J, Wartenberg KE,

Lee K, et al. Resuscitation and critical care of poor-grade

subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurosurgery. 2009;64:397-410. Crossref

5. Guglielmi G, Viñuela F, Dion J, Duckwiler G. Electrothrombosis of

saccular aneurysms via endovascular approach. Part 2: Preliminary clinical experience. J Neurosurg. 1991;75:8-14. Crossref

6. Molyneux AJ, Kerr RS, Yu LM, Clarke M, Sneade M, Yarnold JA, et al. International Subarachnoid Aneurysm Trial (ISAT) Collaborative Group. International subarachnoid aneurysm trial

(ISAT) of neurosurgical clipping versus endovascular coiling in

2143 patients with ruptured intracranial aneurysms: a randomised

comparison of effects on survival, dependency, seizures, rebleeding,

subgroups, and aneurysm occlusion. Lancet. 2005;366:809-17. Crossref

7. Batista LL, Mahadevan J, Sachet M, Alvarez H, Rodesch G,

Lasjaunias P. 5-year angiographic and clinical follow-up of

coil-embolised intradural saccular aneurysms. A single center

experience. Interv Neuroradiol. 2002;8:349-66. Crossref

8. Henkes H, Fischer S, Weber W, Miloslavski E, Felber S, Brew S,

et al. Endovascular coil occlusion of 1811 intracranial aneurysms:

early angiographic and clinical results. Neurosurgery. 2004;54:268-80. Crossref

9. Bradac GB, Bergui M, Stura G, Fontanella M, Daniele D,

Gozzoli L, et al. Periprocedural morbidity and mortality by

endovascular treatment of cerebral aneurysms with GDC: a

retrospective 12-year experience of a single center. Neurosurg

Rev 2007;30:117-26. Crossref