Risk Factors for Early Mortality in Head and Neck Cancer Patients Undergoing Definitive Chemoradiation

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Risk Factors for Early Mortality in Head and Neck Cancer Patients Undergoing Definitive Chemoradiation

T Tsui, KM Cheung, JCH Chow, KH Wong

Department of Clinical Oncology, Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Hong Kong

Correspondence: Dr Therese Tsui, Department of Clinical Oncology, Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Hong Kong. Email: tsui.therese@gmail.com

Submitted: 8 Sep 2021; Accepted: 15 Nov 2021.

Contributors: All authors designed the study, acquired the data, analysed the data, drafted the manuscript, and critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Funding/Support: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data Availability: All data generated or analysed during the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: This study was approved by the Hong Kong Hospital Authority Kowloon Central Cluster/Kowloon East Cluster research ethics committee (Ref: KC/KE-20-0242/ER-1).

Abstract

Introduction

Head and neck cancer (HNC) afflicts >16,000 people in Hong Kong annually. Non-operative treatment

for HNC typically involves radiotherapy (with or without concurrent systemic therapy) and is associated with

significant acute toxicity. Demography, tumour factors, and co-morbidities each influence treatment outcome and

prognosis, but their role in predicting 90-day mortality is less well-known.

Methods

Demographic, clinical, and co-morbidity data of 725 non-metastatic HNC patients (9.4% stage I/II, 90.6%

stage III/IV), who had undergone definitive radiotherapy from 1 January 2016 to 1 March 2020 were collected.

Predictors for 90-day mortality were evaluated by simple and multivariable logistic regression.

Results

We report a 4.6% 90-day mortality rate. Age >60 years(odds ratio [OR] = 3.453, 95% confidence interval [CI] =

1.195-9.928; p = 0.022), Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (OR = 2.184, 95% CI =

1.071-4.454; p = 0.032) and pre-treatment haemoglobin level (OR = 0.764, 95% CI = 0.596-0.979; p = 0.034)

were significant predictors of 90-day mortality on multivariable analysis. Of the eight co-morbidity scores studied,

the Adult Comorbidity Evaluation–27 (ACE-27) [OR = 2.177, 95% CI = 1.397-3.393; p = 0.001] and the Taipei

Medical University–concurrent chemoradiotherapy Mortality Predictor Score (TMU-CCRT ) [OR = 1.501,

95% CI = 1.134-1.986; p = 0.004) were the most significant predictors of 90-day mortality.

Conclusion

Both clinical factors and co-morbidities predict early mortality in HNC patients. ACE-27 and TMU-CCRT

are appropriate for co-morbidity assessment in relation to early mortality. Further studies to develop prospective

models that identify accurately patients at risk of early mortality during treatment are necessary.

Key Words: Comorbidity; Drug therapy; Head and neck neoplasms; Mortality; Prognosis

中文摘要

接受根治性放化療的頭頸癌患者早期死亡的危險因素

徐譽文、張嘉文、周重行、黃錦洪

引言

香港每年有超過16,000人罹患頭頸癌。頭頸癌的非手術治療通常包括放射治療(聯合或不聯合全身性治療),與顯著急性毒性相關。人口統計學、腫瘤和共病症都會影響治療結果和預後,但它們在預測90天死亡率的作用則鮮為人知。

方法

收集2016年1月1日至2020年3月1日期間接受根治性放療的725例非轉移性頭頸癌患者(I/II期佔9.4%、III/IV期佔90.6%)的人口統計學、臨床和共病症數據。通過簡易及多變量邏輯迴歸評估90天死亡率的預測因子。

結果

90天死亡率為4.6%。60歲以上(優勢比3.453,95%置信區間 = 1.195-9.928;p = 0.022)、ECOG表現狀態(優勢比2.184,95%置信區間 = 1.071-4.454;p = 0.032)和治療前血紅蛋白水平(優勢比0.764,95%置信區間 = 0 596-0.979; p = 0.034)是多變量分析中90天死亡率的重要預測因子。在研究的八種共病症評分中,成人共病症評估27量表(ACE-27;優勢比2.177,95%置信區間 = 1.397-3.393; p = 0.001)及臺北醫學大學同步放化療死亡率預測評分(TMU-CCRT;優勢比1.501,95%置信區間 = 1.134-1.986;p = 0.004)是90天死亡率的最重要預測因子。

結論

臨床因素和共病症均可預測頭頸癌患者的早期死亡率。ACE-27和TMU-CCRT適用於與早期死亡率相關的共病症評估。需要進一步研究發展更全面模式以準確識別治療期間有早期死亡風險的患者。

INTRODUCTION

Radiotherapy and chemotherapy are two of the

mainstays of treatment for head and neck cancer

(HNC).[1] Radiotherapy of HNC may cause mucositis,

dermatitis, or dysphagia, whereas addition of

concomitant chemotherapy increases the risk of

myelosuppression, nausea and vomiting, neurotoxicities,

and nephrotoxicities. Although these typically improve

within 6 months after treatment in most patients,[2]

some patients succumb to these toxicities shortly after

treatment.[3] [4] [5] The United Kingdom introduced a 5%

90-day mortality rate following radical radiotherapy in

HNC as a quality metric.[6] [7]

Treatment outcomes in HNC are influenced by a

range of patient and disease factors. Co-morbidity is

a known independent prognosticator for survival in

HNC.[8] [9] There are several co-morbidity scores available

with known prognostic significance in HNC, some of

which are suitable for registry-based and retrospective

assessment.[8] [10]

The most commonly utilised co-morbidity indices are

the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI)[11] and the Adult Comorbidity Evaluation–27 (ACE-27).[12] These have

both been validated in HNC patients.[10] [13] An ACCI

(age-adjusted Charlson Comorbidity Index) is another

established co-morbidity score derived from the CCI and

assigns 1 additional point per decade over 40 years of

age up to 4 points.[14] Although validated in HNC,[15] [16] it is

less widely used than CCI and ACE-27.

There are several assessment tools designed specifically

for HNC patients. The HN-CCI (head and neck

comorbidity index score)[17] and the HNCA (head and

neck cancer index)[18] are both adapted from the CCI.

The WUHNCI (Washington University Head and

Neck Comorbidity Index) contains seven weighted

conditions. It was shown to improve prognostication

over a multivariable regression model comprising

age, sex, race, symptom stage, and TNM stage.[19] The

Simplified Comorbidity Score (SCS) includes seven

co-morbid conditions and smoking status.[20] It was

originally developed for lung cancer patients, but

Göllnitz et al[21] demonstrated its prognostic value in

HNC along with other co-morbidity scores. The Taipei

Medical University–concurrent chemoradiotherapy

(TMU–CCRT) Mortality Predictor Score is the only co-morbidity score developed for prediction of 90-day

mortality post radical chemoradiotherapy in locally

advanced HNC patients.[3]

We sought to assess the 90-day mortality rate after

radical radiotherapy, with or without concurrent systemic

treatment, to identify significant risk factors for early

mortality and to assess the predictive value of different

co-morbidity scores.

METHODS

Patient Cohort

All 1649 consecutive patients treated with radiotherapy

for HNC from 1 January 2016 to 1 March 2020 at a

single tertiary cancer centre were screened for eligibility.

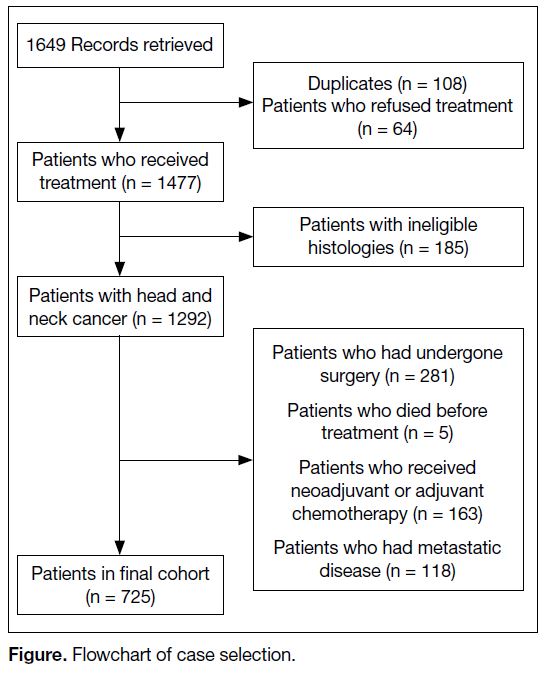

The Figure shows the flowchart for screening. Patients

who were planned for radiotherapy with curative

intent, with or without systemic treatment, as primary

treatment for non-metastatic primary HNC from all sites

and stages were included. To eliminate the effect of

postoperative recovery and chemotherapy before or after

radiotherapy, those who had surgery, and those who

received neoadjuvant or adjuvant chemotherapy with

primary treatment, were excluded. We also excluded

patients who received a planned radiation dose of

<66 Gy to the planning target volume. Patients who were diagnosed with lymphoma, skin malignancies, sarcomas

or thyroid malignancies were excluded. All 725 patients

included in our analysis had received at least 6 months of

follow-up post completion of primary treatment at time

of analysis.

Figure. Flowchart of case selection

Treatment Technique

Radiotherapy to the head and neck region was

administered via intensity-modulated radiotherapy,

volumetric mediated arc therapy, or in the case of

nasopharyngeal cancers (NPC), TomoTherapy.

Radiotherapy doses up to 70-72 Gy in 33 fractions for

NPC and up to 70 Gy in 35 fractions for squamous

HNC were prescribed. Concurrent chemoradiotherapy

regimens included weekly cisplatin 40 mg/m2; cisplatin

100 mg/m2 given once every 3 weeks; or cetuximab

400 mg/m2 1 week before radiotherapy and 250 mg/m2

in subsequent weekly doses until completion of

radiotherapy.

Data Extraction and Calculation of Co-morbidity

Scores

In our study, early mortality was defined as 135 days from start of radiotherapy as a surrogate for 90-day mortality

post radical radiotherapy, assuming a maximum planned

overall treatment time of 45 days.[4]

Manual review and data extraction were performed for

each patient. Demographic information, including age,

sex, body weight and height, smoking history, and alcohol

use were extracted. Eastern Cooperative Oncology

Group (ECOG) performance status was documented.

Tumour site, histology and staging, the results of baseline

swallowing assessment, treatment details including

treatment technique, dose, and concurrent systemic

therapy were logged. Disruptions or unplanned events

warranting medical attention during treatment, including

unplanned feeding tube insertion, admission, or need for

adaptive replanning of radiotherapy were recorded. Start

and end dates of radiotherapy, last date of follow-up, and

date and cause of death were recorded.

Baseline laboratory values including haemoglobin,

white cell count, platelet count, albumin, creatinine,

calcium, and lactate dehydrogenase were retrieved.

Symptom score at presentation, scored as the number of

items present from the following list: dysphagia, otalgia,

weight loss and presence of neck mass, was calculated.[22]

Patient records were reviewed for co-morbidities comprising seven of the eight co-morbidity scores mentioned — CCI, ACCI, HN-CCI, SCS, WUHNCI,

HNCA and TMU-CCRT. The calculation of ACE-27

was assessed directly from electronic medical records.

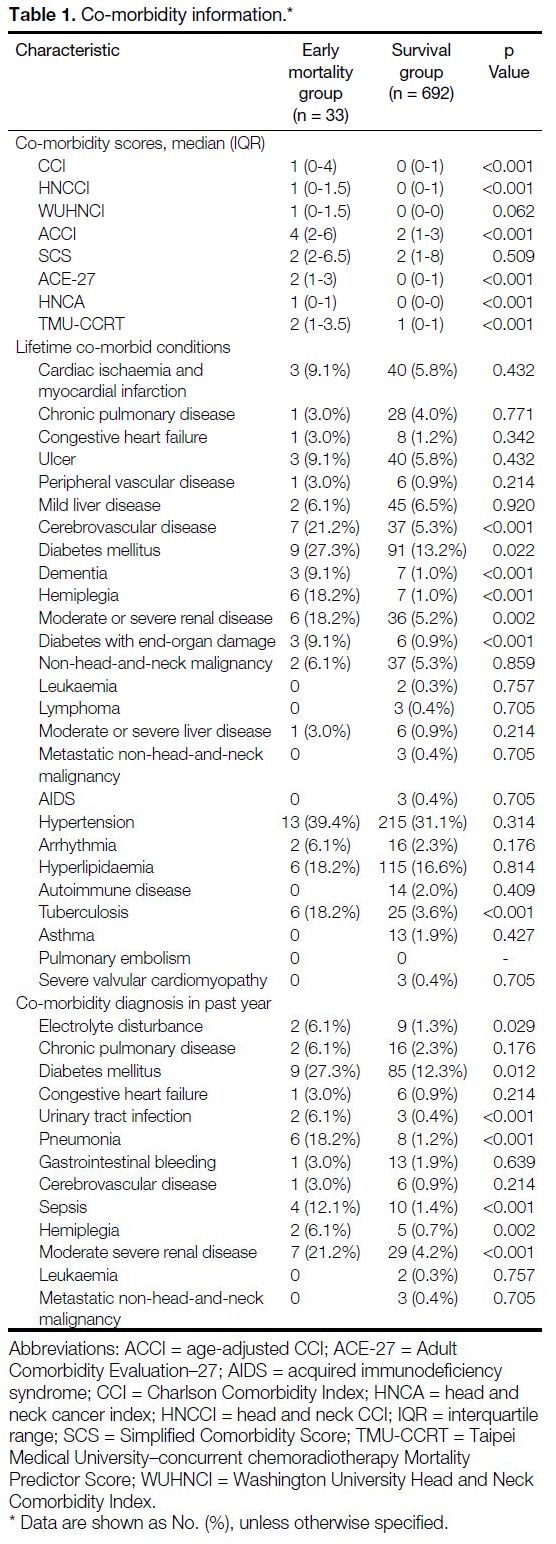

The full list of co-morbidities assessed is shown in

Table 1.

Table 1. Co-morbidity information

Statistical Analysis

The full cohort was analysed for demographic

information. Univariate analysis was performed using

the Chi-square test for categorical data and the Mann-Whitney U test for continuous or ordinal data to compare

the 90-day mortality and survival groups. Multivariable

logistic regression was performed to evaluate the

effect of different variables on 90-day mortality after

chemoradiotherapy, controlling for other covariates. A p

value <0.05 was taken as significant.

RESULTS

In total, among 1649 consecutive patients, 1292 were

treated with radiotherapy for HNC during the study

period from 1 January 2016 to 1 March 2020 (Figure).

After exclusions for prior surgery (n = 281), neoadjuvant

or adjuvant chemotherapy (n = 163), metastatic disease

(n = 118), or death before treatment (n = 5), finally

725 patients were included in our cohort and received

≥6 months of follow-up after completion of radiotherapy

at time of analysis (Figure).

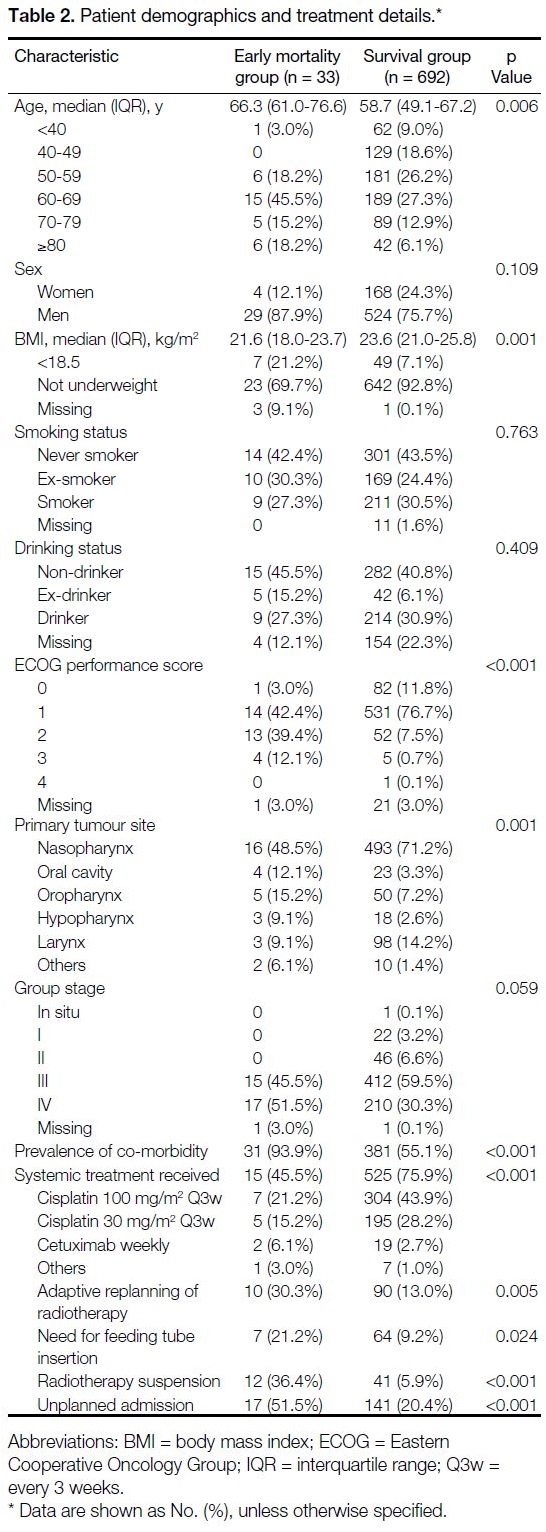

The median age at diagnosis was 59 years. A total of

19.6% were aged >70 years, and 76.3% were male.

Lifetime smokers and drinkers made up 55% and 37%

of cases, respectively. The most common tumour site

was nasopharynx (70.2%), followed by larynx (13.9%),

oropharynx (7.6%), oral cavity (3.7%), hypopharynx

(2.9%), and other sites (1.6%). Locally advanced disease

(stage III/IV) made up 90.6% of cases. A total of 74.1%

received chemotherapy and radiotherapy. The median

follow-up was 23.1 months as of 30 November 2020

(Table 2).

Table 2. Patient demographics and treatment details

In all, 33 out of 725 patients (4.6%) did not survive

beyond 90 days from the end of treatment. Of these, 14

patients (42.4%) died due to pneumonia or sepsis, nine

(27.3%) developed sudden cardiac arrest. Four died

due to distant relapse, and five died due to other causes

including acute kidney injury, pneumoperitoneum, or

deterioration after early termination of treatment. Cause

of death was not available for one patient.

Poorer radiation tolerance was noted in the 90-day

mortality group, with significantly higher rates of adaptive radiotherapy replanning (30.3% vs. 13.0%,

p = 0.005), feeding tube insertion during treatment

(21.2% vs. 9.2%, p = 0.024), radiotherapy suspension

(36.4% vs. 5.9%, p < 0.001) and unplanned admissions

(51.5% vs. 5.9%, p < 0.001).

A total of 57% of cases had at least one co-morbid

condition (Table 1). The 90-day mortality group had

higher median scores across all of the co-morbidity

indices except SCS. A history of stroke (21.2% vs. 5.3%,

p < 0.001), diabetes (27.3% vs. 13.2%, p = 0.022) or

diabetes with complications (9.1% vs. 0.9%, p < 0.001),

dementia (9.1% vs. 1.0%, p < 0.001), hemiplegia (18.2%

vs. 1.0%, p < 0.001) and moderate-to-severe renal

disease (18.2% vs. 5.2%, p = 0.002) were more common

in the 90-day mortality group. Within 1 year of diagnosis

of HNC, electrolyte disturbance (6.1% vs. 1.3%, p = 0.029), sepsis (12.1% vs. 1.4, p < 0.001), pneumonia

(18.2% vs. 1.2%, p < 0.001), and urinary tract infections

(6.1% vs. 0.4%, p < 0.001) were more common in the

90-day mortality group.

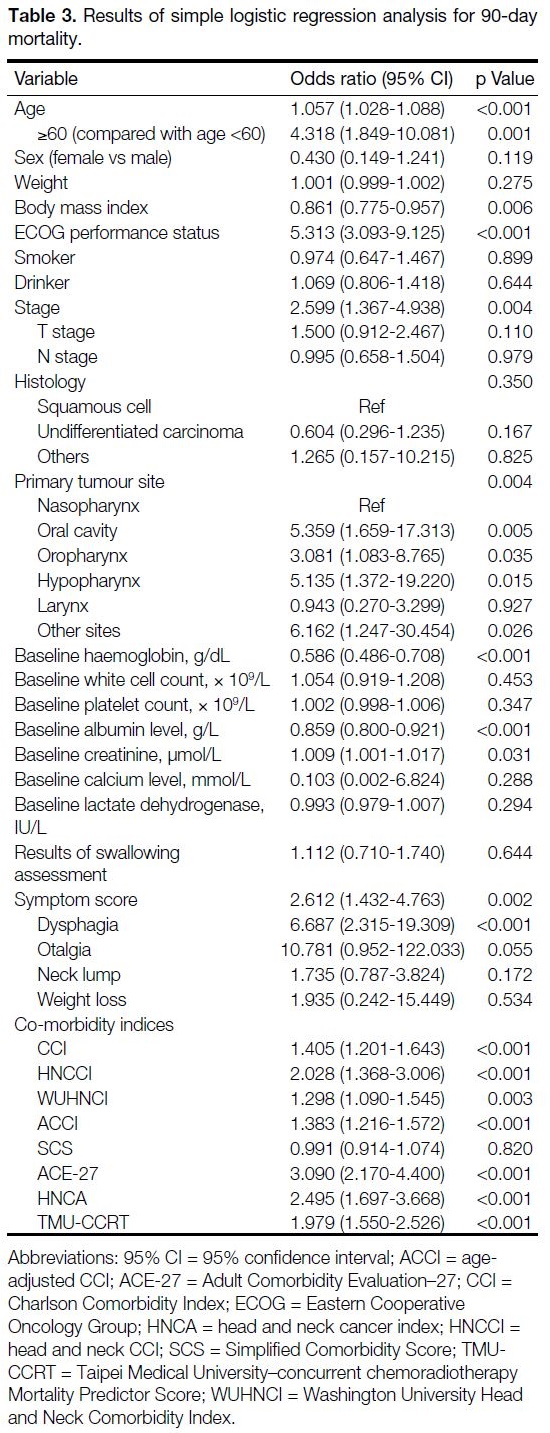

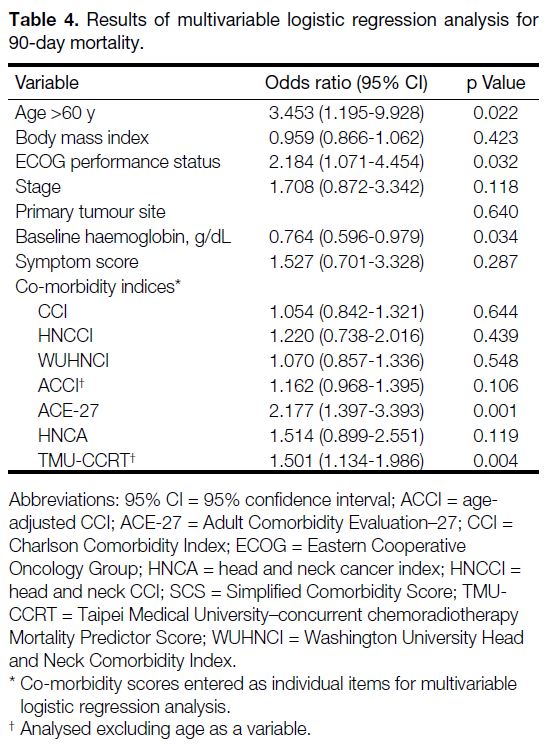

Results of simple logistic regression analysis are shown in Table 3. Multivariable logistic regression analysis

(Table 4) identified age >60, ECOG performance

status, and pre-treatment haemoglobin as significant

independent predictors of 90-day mortality. Of the co-morbidity

indices investigated, when controlled for

clinical parameters, only ACE-27 and TMU-CCRT

remained significant on multivariable regression

analysis.

Table 3. Results of simple logistic regression analysis for 90-day mortality

Table 4. Results of multivariable logistic regression analysis for 90-day mortality

DISCUSSION

Our study found a 4.6% 90-day post-treatment mortality rate, which was within the 5% cut-off per the National

Institute of Clinical Excellence and the Scottish Cancer

Taskforce recommendations.[6] [7] Other real-world cohorts

have reported early mortality rates of 5% to 18%.[3] [23] [24]

Historical randomised controlled trials, which reported

early mortality rates of 1% to 5%, defined the early

mortality period differently, ranging from 30 days from

end of treatment to 90 days from the start of treatment.[25] [26] [27]

As in our cases, the addition of chemotherapy in these

studies was associated with a lower early mortality

rate, although this difference is likely attributable to

confounding due to selection of fitter patients for more

intensive treatment.[25] [26] [27]

Early mortality in NPC is less studied compared to locally

advanced squamous cell carcinomas. Despite sharing

similar radiotherapy doses, organs at risk and systemic treatment regimens, NPC, having a different aetiology

and clinical course, has been purposely excluded

from HNC studies to facilitate long-term prognostic

analysis.[3] [4] [5] In our study, we included NPC, which made

up 69.9% of our cases, due to similarities in primary

treatment between NPC and locally advanced HNCs.

A similar acute toxicity profile is expected. Our results

confirm that the risk of early mortality, after adjusting for

different clinical parameters, is not significantly different

in patients with squamous cell HNC of other primary

sites.[4]

Multivariable logistic regression analysis identified age,

ECOG performance status, and haemoglobin levels as

significant predictors of early mortality. The effect of

age and performance status on prognosis in HNC is well-known.[28] Elderly and frail patients were traditionally

excluded from HNC trials,[25] [26] [27] although exclusion based

on age alone is no longer recommended on the basis of

evidence showing no significant differences in objective

acute toxicity measurements or late toxicity across

different age cut-offs for radical radiotherapy.[29] In patients

aged >70 years, however, the addition of chemotherapy yielded no survival benefit.[1] In our study, we showed that

increasing age remained an important predictor for early

mortality. Performance status is often used as a proxy

for burden of co-morbidity, but other studies have shown

that it provides prognostic information independent of

co-morbidity.[30] [31] The retention of ECOG performance

status with certain co-morbidity indices in multivariable

logistic regression analysis confirms that both have

important implications in predicting early mortality.

In squamous cell HNCs, pre-treatment co-morbidity has

consistently been identified as an important independent

prognosticator. The role of co-morbidity in NPC is

less pronounced, as the Epstein–Barr virus, rather

than alcohol and tobacco exposure, is the dominant

aetiological factor. Despite this, we found ACE-27

and TMU-CCRT to be independent predictors of early

mortality after adjusting for baseline demographic

factors. ACE-27 is widely used for co-morbidity

assessment across different cancers; it has been shown

to predict severe acute toxicity, early mortality, as well

as long-term prognosis in HNC.[4] [10] [32] [33] ACE-27 differs

from other co-morbidity indices covered here in that

it grades overall severity of co-morbidity from 0 (no

co-morbidity) to 3 (severe co-morbidity).[12] It also covers

a wider scope of co-morbid conditions compared with

other co-morbidity indices under review.[10] Currently, it

is the recommended standard for recording co-morbidity

data in the United Kingdom.[34] TMU-CCRT scores

patients for early mortality risk based on stratified age

and six other co-morbid conditions.[3] Our results validate

the role of TMU-CCRT as a predictor of early mortality

in HNC.

Based on median scores in the 90-day mortality and

survival groups, ACE-27 was best able to differentiate

between severity levels of co-morbidity. An ACE-27

score of 2 corresponds to a moderate level of co-morbidity,

while a score of 0 corresponds to no co-morbidity. In

contrast, the median scores for TMU-CCRT in the

90-day mortality and survival groups both fell into the

low-risk category based on the proposed stratification

by Lin et al.[3] This illustrates the need for universally

appropriate cut-offs for clinical use. Our review of

the current literature found that, apart from ACE-27,

different cut-offs have been utilised by different groups

to delineate the co-morbidity burden.

Pre-treatment laboratory values are relatively

less investigated as prognostic markers.[24] These

haematological and biochemical markers may reflect baseline co-morbidity, but not all mechanisms by which

they affect survival or treatment outcomes are well

understood. In our study, we found that haemoglobin

levels below the lower limit of normal was associated

with early mortality. In HNC, anaemia is associated with

higher recurrence rates and poorer overall survival,[21] [35] an

effect attributed to decreased efficacy of treatment due to

tumour hypoxia and decreased radiosensitivity.[36] [37] Other

studies have also demonstrated that early mortality was

more likely in patients with baseline anaemia.[4] After

controlling for other factors, other blood parameters

were not correlated with early mortality in our cases.

Sepsis and pneumonia were the most common causes

of death among patients who died within 90 days after

completing treatment. Radiotherapy to the head and

neck often causes acute toxicities such as mucositis,

dysphagia, and odynophagia, increasing the risk of

aspiration.[38] Eisbruch et al[39] reported aspiration rates up

to 65% within 3 months after radiotherapy, while other

studies have found aspiration pneumonia rates up to

17.6%.[40] This may be exacerbated by concomitant use

of chemotherapy or biologics. Collapse or cardiac events

were the second most common, supporting previous

work that suggested higher risk of cardiovascular events

in cancer patients.[41]

Despite attempts to identify risk factors for early mortality

following radical treatment for HNC, the optimal case

selection criteria for intensive treatment remains elusive.

Substandard treatment is independently associated with

poorer survival after adjusting for other factors such

as performance status, age, and mild co-morbidity,[42]

emphasising the need for comprehensive assessment of

fitness for treatment.

There are several limitations to our study. Our data

were obtained from a single tertiary cancer centre and

consisted of predominantly NPC patients. Analysis from

a population-based database and further validation in

squamous cell HNC population is necessary to confirm

generalisability of our results. Second, information

regarding baseline functional status or socioeconomic

status was not available from retrospective review of

patient records. These are potentially important factors in

predicting tolerance to treatment.[43] [44] Crucially, although

presence of one or more these factors indicates a higher

odds of mortality, this does not definitively identify

patients who will suffer early death within 90 days after

treatment; as such, these factors should not be used to

exclude patients from potentially curative treatment. The best course of action in an individual with multiple risk

factors is not known and the formulation of any treatment

plan requires careful discussion with the patient.

CONCLUSION

Minimising early treatment mortality is important for

optimising outcomes of patients with HNC. The 90-day

mortality rate after radical radiotherapy, with or without

concurrent systemic treatment, in our cohort was 4.6%.

Age, pre-treatment Hb, ECOG performance status,

and two co-morbidity indices: ACE-27 and TMU-CCRT,

were found to be independent predictors of

early mortality. Development of a more comprehensive

prediction model from these factors may help with case

selection of patients for intensive HNC treatment.

REFERENCES

1. Pignon JP, le Maître A, Maillard E, Bourhis J, MACH-NC

Collaborative Group. Meta-analysis of chemotherapy in head and

neck cancer (MACH-NC): an update on 93 randomised trials and

17,346 patients. Radiother Oncol. 2009;92:4-14. Crossref

2. Rathod S, Gupta T, Ghosh-Laskar S, Murthy V, Budrukkar A,

Agarwal J. Quality-of-life (QOL) outcomes in patients with

head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) treated with

intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) compared to three-dimensional

conformal radiotherapy (3D-CRT): evidence from a

prospective randomized study. Oral Oncol. 2013;49:634-42. Crossref

3. Lin KC, Chen TM, Yuan KS, Wu AT, Wu SY. Assessment of

predictive scoring system for 90-day mortality among patients

with locally advanced head and neck squamous cell carcinoma

who have completed concurrent chemoradiotherapy. JAMA Netw

Open. 2020;3:e1920671. Crossref

4. Dixon L, Garcez K, Lee LW, Sykes A, Slevin N, Thomson D.

Ninety day mortality after radical radiotherapy for head and neck

cancer. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 2017;29:835-40. Crossref

5. Hamilton SN, Tran E, Berthelet E, Wu J, Olson R. Early (90-day)

mortality after radical radiotherapy for head and neck squamous cell

carcinoma: a population-based analysis. Head Neck. 2018;40:2432-40. Crossref

6. National Institute for Clinical Excellence. Improving outcomes in

head and neck cancers. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/csg6. Accessed 7 Jun 2022.

7. Scottish Cancer Taskforce. Head and neck cancer clinical quality

performance indicators. Patients diagnosed during April 2014 to

March 2015. Available from: https://www.isdscotland.org/Health-Topics/Quality-Indicators/Publication.... Accessed 7 Jun 2022.

8. Bøje CR. Impact of comorbidity on treatment outcome in head and

neck squamous cell carcinoma — a systematic review. Radiother

Oncol. 2014;110:81-90. Crossref

9. Paleri V, Wight RG, Silver CE, Haigentz M Jr, Takes RP,

Bradley PJ, et al. Comorbidity in head and neck cancer: a

critical appraisal and recommendations for practice. Oral Oncol.

2010;46:712-9. Crossref

10. Rogers SN, Aziz A, Lowe D, Husband DJ. Feasibility study of

the retrospective use of the Adult Comorbidity Evaluation index

(ACE-27) in patients with cancer of the head and neck who had

radiotherapy. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2006;44:283-8. Crossref

11. Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies:

development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373-83. Crossref

12. Piccirillo JF. Importance of comorbidity in head and neck cancer. Laryngoscope. 2000;110:593-602. Crossref

13. Singh B, Bhaya M, Stern J, Roland JT, Zimbler M, Rosenfeld RM,

et al. Validation of the Charlson comorbidity index in patients with

head and neck cancer: a multi-institutional study. Laryngoscope.

1997;107:1469-75. Crossref

14. Charlson M, Szatrowski TP, Peterson J, Gold J. Validation of a combined comorbidity index. J Clin Epidemiol. 1994;47:1245-51. Crossref

15. Tanaka H, Takenaka Y, Nakahara S, Hanamoto A, Fukusumi T,

Michiba T, et al. Age-adjusted Charlson comorbidity index

as a prognostic factor of hypopharyngeal cancer treated with

chemoradiation therapy. Acta Otolaryngol. 2017;137:668-73. Crossref

16. Yang CC, Chen PC, Hsu CW, Chang SL, Lee CC. Validity of the

age-adjusted Charlson comorbidity index on clinical outcomes

for patients with nasopharyngeal cancer post radiation treatment:

a 5-year nationwide cohort study. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0117323. Crossref

17. Bøje CR, Dalton SO, Primdahl H, Kristensen CA, Andersen E,

Johansen J, et al. Evaluation of comorbidity in 9388 head and

neck cancer patients: a national cohort study from the DAHANCA

database. Radiother Oncol. 2014;110:91-7. Crossref

18. Reid BC, Alberg AJ, Klassen AC, Rozier RG, Garcia I, Winn DM,

et al. A comparison of three comorbidity indexes in a head and neck

cancer population. Oral Oncol. 2002;38:187-94. Crossref

19. Piccirillo JF, Lacy PD, Basu A, Spitznagel EL. Development of

a new head and neck cancer-specific comorbidity index. Arch

Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2002;128:1172-9. Crossref

20. Colinet B, Jacot W, Bertrand D, Lacombe S, Bozonnat MC,

Daurès JP, et al. A new simplified comorbidity score as a prognostic

factor in non-small-cell lung cancer patients: description and

comparison with the Charlson’s index. Br J Cancer. 2005;93:1098-105. Crossref

21. Göllnitz I, Inhestern J, Wendt TG, Buentzel J, Esser D, Böger D,

et al. Role of comorbidity on outcome of head and neck cancer:

a population-based study in Thuringia, Germany. Cancer Med.

2016;5:3260-71. Crossref

22. Pugliano FA, Piccirillo JF, Zequeira MR, Fredrickson JM,

Perez CA, Simpson JR. Symptoms as an index of biologic

behavior in head and neck cancer. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg.

1999;120:380-6. Crossref

23. Capuano G, Grosso A, Gentile PC, Battista M, Bianciardi F, Di Palma A, et al. Influence of weight loss on outcomes in patients with head and neck cancer undergoing concomitant chemoradiotherapy. Head Neck. 2008;30:503-8. Crossref

24. Schlumpf M, Fischer C, Naehrig D, Rochlitz C, Buess M. Results

of concurrent radio-chemotherapy for the treatment of head and

neck squamous cell carcinoma in everyday clinical practice with

special reference to early mortality. BMC Cancer. 2013;13:610. Crossref

25. Adelstein DJ, Li Y, Adams GL, Wagner H Jr, Kish JA, Ensley JF,

et al. An intergroup phase III comparison of standard radiation

therapy and two schedules of concurrent chemoradiotherapy in

patients with unresectable squamous cell head and neck cancer. J

Clin Oncol. 2003;21:92-8. Crossref

26. Cooper JS, Pajak TF, Forastiere AA, Jacobs J, Campbell BH,

Saxman SB, et al. Postoperative concurrent radiotherapy and

chemotherapy for high-risk squamous-cell carcinoma of the head

and neck. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1937-44. Crossref

27. Forastiere AA, Goepfert H, Maor M, Pajak TF, Weber R,

Morrison W, et al. Concurrent chemotherapy and radiotherapy for

organ preservation in advanced laryngeal cancer. N Engl J Med.

2003;349:2091-8. Crossref

28. Sze HC, Ng WT, Chan OS, Shum TC, Chan LL, Lee AW. Radical radiotherapy for nasopharyngeal carcinoma in elderly patients: the importance of co-morbidity assessment. Oral Oncol. 2012;48:162-7. Crossref

29. Pignon T, Horiot JC, Van den Bogaert W, Van Glabbeke M,

Scalliet P. No age limit for radical radiotherapy in head and neck

tumours. Eur J Cancer. 1996;32A:2075-81. Crossref

30. Wang JR, Habbous S, Espin-Garcia O, Chen D, Huang SH,

Simpson C, et al. Comorbidity and performance status as

independent prognostic factors in patients with head and neck

squamous cell carcinoma. Head Neck. 2016;38:736-42. Crossref

31. Extermann M, Overcash J, Lyman GH, Parr J, Balducci L. Comorbidity and functional status are independent in older cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:1582-7. Crossref

32. Monteiro AR, Garcia AR, Pereira TC, Macedo F, Soares RF,

Pereira K, et al. ACE-27 as a prognostic tool of severe acute

toxicities in patients with head and neck cancer treated with

chemoradiotherapy: a real-world, prospective, observational study.

Support Care Cancer. 2021;29:1863-71. Crossref

33. Sanabria A, Carvalho AL, Vartanian JG, Magrin J, Ikeda MK,

Kowalski LP. Validation of the Washington University Head

and Neck Comorbidity Index in a cohort of older patients. Arch

Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008;134:603-7. Crossref

34. Robson A, Sturman J, Williamson P, Conboy P, Penney S, Wood H.

Pre-treatment clinical assessment in head and neck cancer: United

Kingdom National Multidisciplinary Guidelines. J Laryngol Otol.

2016;130:S13-22. Crossref

35. Lee WR, Berkey B, Marcial V, Fu KK, Cooper JS, Vikram B, et al.

Anemia is associated with decreased survival and increased

locoregional failure in patients with locally advanced head and

neck carcinoma: a secondary analysis of RTOG 85-27. Int J Radiat

Oncol Biol Phys. 1998;42:1069-75. Crossref

36. Caro JJ, Salas M, Ward A, Goss G. Anemia as an independent

prognostic factor for survival in patients with cancer: a systemic, quantitative review. Cancer. 2001;91:2214-21. Crossref

37. Hoff CM. Importance of hemoglobin concentration and its

modification for the outcome of head and neck cancer patients

treated with radiotherapy. Acta Oncol. 2012;51:419-32. Crossref

38. Russi EG, Corvò R, Merlotti A, Alterio D, Franco P, Pergolizzi S, et al.

Swallowing dysfunction in head and neck cancer patients treated

by radiotherapy: review and recommendations of the supportive

task group of the Italian Association of Radiation Oncology. Cancer

Treat Rev. 2012;38:1033-49. Crossref

39. Eisbruch A, Lyden T, Bradford CR, Dawson LA, Haxer MJ,

Miller AE, et al. Objective assessment of swallowing dysfunction

and aspiration after radiation concurrent with chemotherapy for

head-and-neck cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2002;53:23-8. Crossref

40. Kawashita Y, Morimoto S, Tashiro K, Soutome S, Yoshimatsu M,

Nakao N, et al. Risk factors associated with the development of

aspiration pneumonia in patients receiving radiotherapy for head

and neck cancer: retrospective study. Head Neck. 2020;42:2571-80. Crossref

41. Fang F, Fall K, Mittleman MA, Sparén P, Ye W, Adami HO, et al. Suicide and cardiovascular death after a cancer diagnosis. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1310-8. Crossref

42. Sanabria A, Carvalho AL, Vartanian JG, Magrin J, Ikeda MK,

Kowalski LP. Factors that influence treatment decision in older

patients with resectable head and neck cancer. Laryngoscope.

2007;117:835-40. Crossref

43. Hamaker ME, Jonker JM, de Rooij SE, Vos AG, Smorenburg CH,

van Munster BC. Frailty screening methods for predicting outcome

of a comprehensive geriatric assessment in elderly patients with

cancer: a systematic review. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:e437-44. Crossref

44. Gaubatz ME, Bukatko AR, Simpson MC, Polednik KM, Boakye EA,

Varvares MA, et al. Racial and socioeconomic disparities associated

with 90-day mortality among patients with head and neck cancer

in the United States. Oral Oncol. 2019;89:95-101. Crossref