Online Psychological Intervention in Breast Cancer Survivors: a Review

REVIEW ARTICLE

Online Psychological Intervention in Breast Cancer Survivors: a Review

M Popovic1, V Rico1, C DeAngelis1, H Lam1, FMY Lim2

1 Odette Cancer Centre, Sunnybrook Health Science Centre, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada

2 Department of Oncology, Prince Margaret Hospital, Hong Kong

Correspondence: Dr FMY Lim, Department of Oncology, Prince Margaret Hospital, Hong Kong. Email: fionalimmy@gmail.com

Submitted: 25 Mar 2020; Accepted: 23 Dec 2020.

Contributors: All authors designed the study. MP and VR acquired the data. All authors analysed the data. MP draft the manuscript. All authors critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Funding/Support: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data Availability: All data generated or analysed during the present study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgement: We thank the generous support of Bratty Family Fund, Michael and Karyn Goldstein Cancer Research Fund, Joey and Mary Furfari Cancer Research Fund, Pulenzas Cancer Research Fund, Joseph and Silvana Melara Cancer Research Fund, and Oteia Cancer Research

Fund.

Abstract

Introduction

Online psychotherapy has shown promise in a variety of settings. The goal of this review was to

compare outcomes following online psychotherapy in breast cancer survivors.

Methods

We searched Ovid MEDLINE for randomised controlled trials investigating the benefit of online

psychotherapy relative to controls in breast cancer survivors. We sought to capture data on a standardised pre- and

post-intervention symptom scale. Baseline characteristics were collected, including highest education level achieved,

breast cancer treatment, and description and duration of the psychosocial intervention. Trials were stratified based

on behavioural or psychological indications for treatment. Effect sizes were computed using Cohen’s d.

Results

From an initial search of 99 articles, 838 participants across five relevant studies were included. The

mean age of the women was 51.7 years (range, 50.2-56.9). Each study had a unique indication: insomnia, fatigue,

sexual dysfunction, psychological adjustment, and stress management. Two primary and one secondary outcome

were recorded for each study, for a total of 15. Of the 10 included primary outcomes, women in the intervention

groups showed a statistically significant improvement in nine outcomes. Of the five secondary outcomes, women

in the intervention groups showed a significant improvement on four scales. Effect sizes ranged from 0.33 to 1.10.

Conclusion

Overall, online psychotherapies are effective across a variety of symptom states in breast cancer

survivors. Limitations of online psychotherapy include logistical factors, privacy, personal factors, and availability.

Future studies should compare in-person psychotherapy with online psychotherapy.

Key Words: Internet-based intervention; Psychotherapy; Patient reported outcome measures; Breast neoplasms; Cancer survivors

中文摘要

乳癌康復者線上心理干預的綜述

M Popovic、V Rico、C DeAngelis、H Lam、林美瑩

引言

線上心理治療已在各種場景中顯示其前景。本綜述旨在比較乳癌康復者接受線上心理治療後的效果。

方法

我們從Ovid MEDLINE 搜索隨機對照研究,用以檢視接受線上心理治療的乳癌康復者相比對照組的益處。我們試圖在標準化的干預前和干預後症狀量表上獲取數據。收集基線特徵,包括康復者的教育水平、乳癌治療方案及心理社會干預的描述和持續時間。根據治療的行為或心理指徵對研究進行分層。使用Cohen’s d 計算效應量。

結果

從最初搜索的99份文獻中,納入5份相關研究涉及838名參與者均為女性,平均年齡51.7歲(介乎50.2-56.9歲)。這5項研究分別針對不同的適應症,包括失眠、疲勞、性功能障礙、心理調節和壓力管理,記錄共15個主要結果和次要結果。每項研究分別記錄2個主要結果和1個次要結果。干預組在其中9個主要結果以及5個次要結果中的4個量表均有顯著改善。效應大小範圍介乎0.33至1.10。

結論

總體而言,線上心理治療能有效改善乳癌康復者的多種症狀。線上心理治療的局限性包括後勤因素、隱私、個人因素和可獲取性。未來研究應考慮將面對面的心理治療與線上心理治療進行比較。

INTRODUCTION

Psychotherapy is an interpersonal process designed

to modify several aspects of an individual’s psycho-emotional

state, including feelings, cognition, and

behaviours. Several different types of psychotherapies

(e.g., cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT), interpersonal

therapy, psychodynamic therapy) have been shown to

be efficacious.[1] [2] Data have shown that psychotherapy

has an efficacy similar to that of psychotropic drugs

for disorders such as anxiety and depression,[3] [4] with a

moderate-to-large effect size for depression (d= -0.66,

95% confidence interval [CI]= -0.73 to -0.60) compared

to waitlist controls.[2] [4]

Cancer is a common disease, representing the second

leading cause of death in the United States.[5] Both

cancer itself,[6] and its associated therapies, such as

chemotherapy,[7] produce physical and psychological

adverse effects. The reaction to a cancer diagnosis

can cause neuropsychological stress, such as anxiety,

depression, and fear of recurrence or death, all of which

can adversely impact a patient’s quality of life.[6] There

is increasing support for integrating psychotherapy

in oncology practice. For example, Saeedi et al[6] and

Breitbart et al[8] found that psychotherapy increased the perceived meaning of life[6] and quality of life[8] of cancer

patients, respectively, relative to traditional care. This

supports the notion that psychotherapy can improve a

variety of symptoms in cancer patients.

Given the advances in electronic communication in

the past several decades, there has been increasing

interest in online psychotherapy as an alternative to

face-to-face therapy. Chakrabarti[9] reviewed studies

performing this comparison. The results revealed that

online psychotherapy is reliable, and outcomes are

comparable to that of in-person psychotherapy in many

heterogeneous samples for a variety of measures. These

findings suggest that online psychotherapy may be seen

as a viable alternative to traditional psychotherapy, due

to its similar efficacy for various populations. Due to the

nature of CBT, such as a heavy focus on skills training

and homework, it is the therapeutic approach that is

easiest to transfer to an online format.[10]

There are several studies that have examined the efficacy

of online psychotherapy for breast cancer patients.

Cheung et al[11] aimed to teach women with metastatic

breast cancer positive affect skills through an online

intervention paradigm. Intervention participants showed reductions in both depression and negative affect by the

1-month follow-up (d= -0.81). These participants fell

below the clinical threshold for depression at follow-up,

whereas control participants did not fall below clinical

threshold.

Despite the positive oncologic treatment outcomes that

are experienced by many patients with breast cancer,

psycho-emotional, behavioural, and physical symptoms

may still persist even after breast cancer has been treated

and/or cured.[12] Such challenges tend to be overlooked by

healthcare professionals, since the individual has been

deemed ‘cured’,[13] resulting in reduced support when

transitioning from active cancer to the survivorship

stage. A study conducted by Mitchell[13] examined the

occurrence of depression in long-term survivors of

breast cancer, and found that 10% of these individuals

exhibited clinical depression, despite being diagnosed

≥3 years prior. Another study[12] looked at the

symptomology of breast cancer survivors (BCS) and

described four presentation classes: symptoms within

normal limits, pain with fatigue and sleep disturbances,

depression with fatigue and symptom disturbances,

and high symptom burden. Other issues that have been

linked to additional stress for BCS are the financial

burdens associated with treatment,[14] and a fear of cancer

recurrence.[15] This suggests that when women shift to the

survivor stage of breast cancer, there are still a multitude

of factors that can trigger or exacerbate psychological

symptomatology.

The purpose of this review was to examine the efficacy

of online therapy treatments for BCS. By identifying

useful therapies, we aimed to raise awareness of useful

support available for BCS.

METHODS

Search Strategy, Inclusion Criteria, Study

Selection

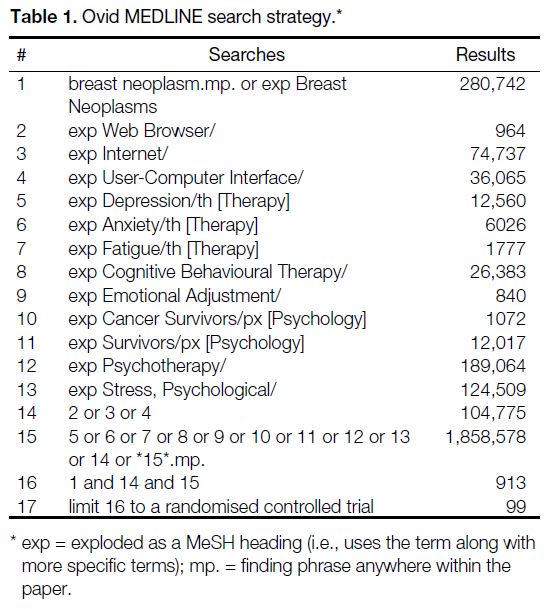

A literature search was conducted using Ovid MEDLINE

and MEDLINE In-Process (inception to July 2019) to

identify relevant studies (Table 1). Articles were eligible

for inclusion if they (1) were a randomised controlled trial

(RCT), (2) included only adult BCS (aged ≥18 years),

(3) compared online psychosocial therapy to any control

group not receiving psychotherapy; and (4) provided

baseline information and post-intervention psycho-emotional

outcomes. One reviewer (MP) screened the

identified search results in a two-stage process, with a title

and abstract screening followed by a full-text screening. Studies that met all criteria were included in the review.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and

Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) reporting guidelines were

implemented in the preparation of the manuscript.

Table 1. Ovid MEDLINE search strategy.

Data Extraction

Data extraction was completed independently by two

authors (MP and VR). Information extracted included

studies at baseline: country of origin, number of

participants in both the intervention and control groups,

age, education, type and duration of treatment for breast

cancer, as well as the type and duration of psychotherapy

received.

Data Analysis

Studies were divided into subgroups based on indications

for psychotherapy. For each included study, baseline

demographics and study endpoints were reported using

descriptive statistics. For continuous parameters, means

and standard deviations were reported where available,

while categorical variables were reported as proportions

of the study sample. Commercial software (Microsoft

Excel; Microsoft, Inc., Redmond [WA], United States)

was used to collect all data. Study statistics were

summarised, and a p value < 0.05 was used as a threshold

to establish statistical significance.

RESULTS

Study Inclusions and Baseline Characteristics

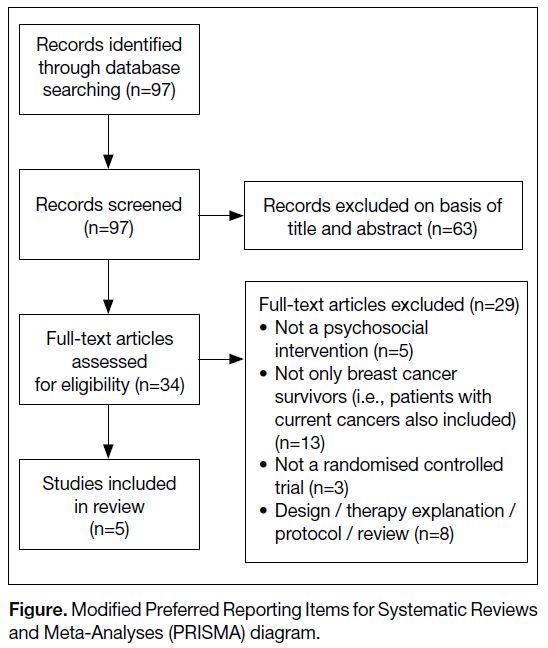

The database search revealed a total of 97 articles,

63 of which were excluded in title and abstract screening

(Figure). Twenty-nine articles were then excluded in the

full-text screening stage, leaving five studies with a total

of 838 participants at baseline and 719 at final follow-up.

[16] [17] [18] [19] [20]

Figure. Modified Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) diagram.

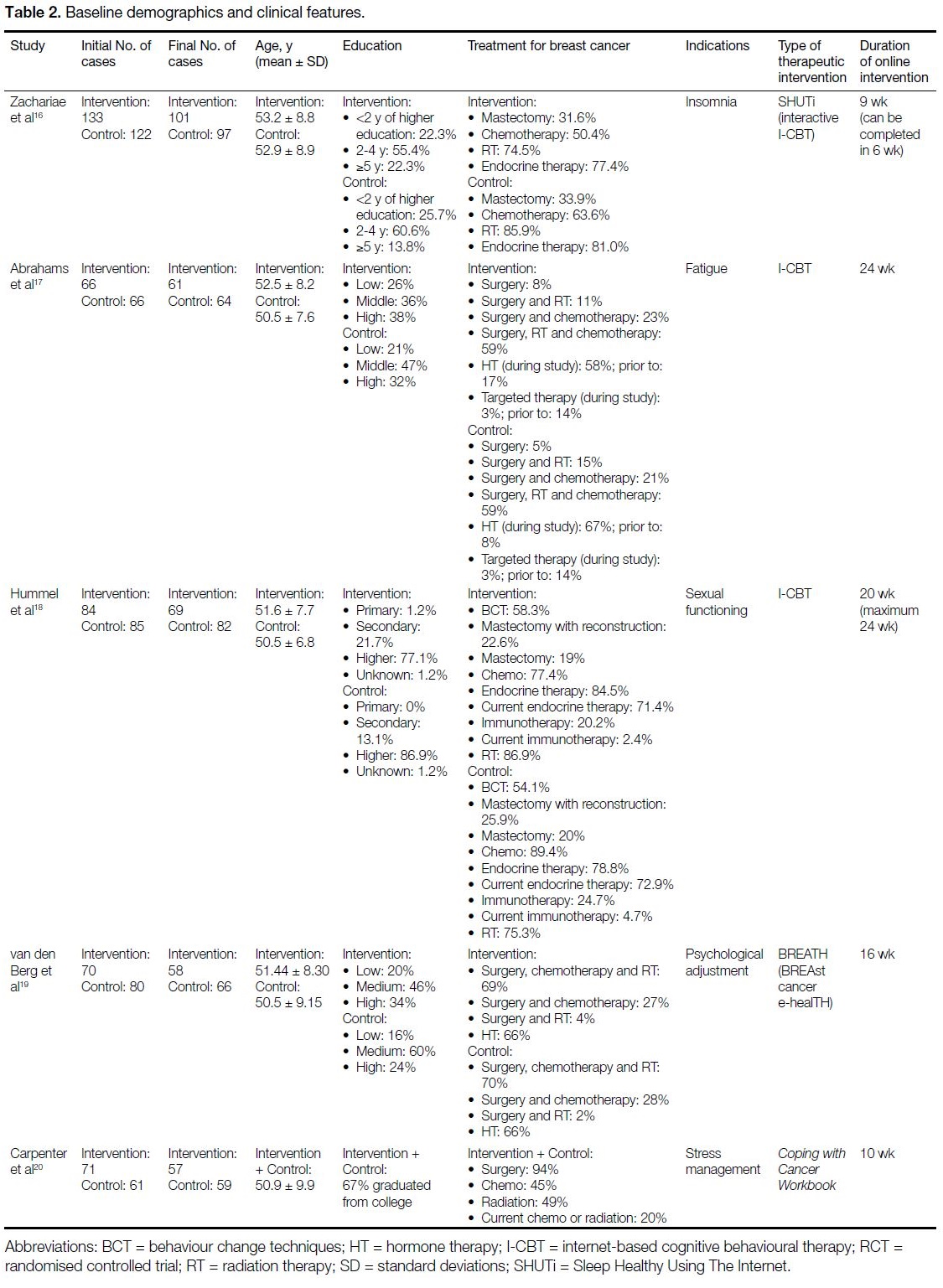

Baseline characteristics of participants and clinical

features of the online psychotherapies are shown in

Table 2. All five studies were RCTs.[16] [17] [18] [19] [20] Across the five

included studies, all participants were female and were

BCS. The mean age was 51.7 years (range = 50.2-56.9).

Education levels of the women varied, with most women

having completed some higher education. Treatments

that were received by participants included surgery,

chemotherapy, radiation therapy, endocrine/hormone

therapy, immunotherapy, or a combination of treatments

(Table 2). Stages of cancer included stage 0 to III,[16] [20]

stages I-III,[17] stages T1-T4,[18] and not specified.[19]

Patients that were not cancer-free, or that experienced

any recurrence, were removed from the study. Each

study specified diagnoses and/or treatment completion

timeframe for inclusion prior to recruitment. Online

psychotherapy ranged from 6 weeks[16] to 24 weeks,[17] with a mean duration of 15.1 weeks. The included studies

involved CBT[16] [17] [18] or incorporated certain properties of

CBT.[19] [20]

Table 2. Baseline demographics and clinical features.

Behavioural Indications

Zachariae et al[16] assessed internet-delivered CBT for

insomnia, which consisted of six cores which aimed

to improve patients’ sleep hygiene. Participants were

included in the study if they suffered from insomnia,

which was defined as a score >5 on the Pittsburgh Sleep

Quality Index (PSQI),[21] with higher scores representing

poorer sleep quality. They randomised 133 participants to

the intervention group and 122 participants to the control

group. The online therapy (SHUTi [Sleep Healthy Using

The Internet])[22] was interactive internet-delivered CBT

for insomnia (Table 2). SHUTi can be completed in

6 weeks, but participants were given 9 weeks to complete

the modules. Researchers performed a pre-assessment,

and a final follow-up 15 weeks later. Primary outcomes

were tested using the PSQI for sleep quality and using

the Insomnia Severity Index[23] for insomnia severity.

A secondary outcome, fatigue, was tested using the

FACIT-F (Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness

Therapy–Fatigue[24]). Baseline parameters between the

intervention and control groups were similar for all three

scales (p > 0.05). Following the intervention, a greater

proportion of participants in the intervention group

reported better sleep quality, lower insomnia severity

(p < 0.0001), and lower fatigue levels (p < 0.001)

compared to controls. The proportion of participants who

no longer met the criteria for PSQI >5 was much higher

for participants in the intervention arm as compared to

the control group (p = 0.011).

Abrahams et al[17] examined an eight-module online

CBT for severe fatigue in a sample of BCS in the

Netherlands. The sample consisted of 66 women in

the intervention group, and 66 women in usual care as

the control group. To be included in the study, patients

had to have significant fatigue based on a score of ≥35

on the Checklist Individual Strength–Fatigue Severity

subscale.[25] Participants initiated their internet-based

CBT (I-CBT) first with two in-person sessions with a

therapist, and then subsequent online sessions (Table 2).

Participants aimed to work on improving their fatigue

and related symptoms. At baseline, both groups were

well beyond the cut-off of 35 on the Checklist Individual

Strength–Fatigue Severity subscale, indicating severe

fatigue. After 6 months, scores of both groups decreased,

however, the women in the intervention group had

significantly lower levels of fatigue (mean difference: p < 0.0001). Similar improvements in functional

impairment (using the Sickness Impact Profile 8[26])

and psychological distress (using the Brief Symptom

Inventory 18[27]) were also demonstrated. Scores of both

groups were similar at baseline, however after 6 months,

a larger improvement was seen in the intervention

group, both for functional impairment and psychological

distress, with a significant mean difference (p < 0.0001).

In total, 73% of patients in the I-CBT group had

improved fatigue symptoms and/or severity, while only

28% women in the control group improved.[17]

Hummel et al[18] conducted a study in the Netherlands

looking at the efficacy of online psychotherapy for sexual

functioning in BCS. The intervention group consisted

of 84 women, while the control group consisted of 85

individuals. All women had to have a prior Diagnostic and

Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders Text Revision,

4th edition[28] diagnosis of sexual dysfunction. The

therapy was guided by one of four female psychologists/sexologists. The 10-module I-CBT was composed of

approximately 20 weekly sessions that were completed

in 24 weeks (Table 2). The goal of the intervention was

to improve sexual functioning, relationship intimacy

and body image. The primary outcome was based on

the Female Sexual Function Index,[29] which looked at

sexual functioning; higher scores indicate better sexual

functioning. The study also evaluated sexual pleasure via

the Sexual Activity Questionnaire Pleasure subscale,[30]

and sexual distress via the Female Sexual Distress Scale–Revised.[31] At pre-assessment, the intervention group was

similar to the control group on all three measures, while at

the post-assessment, sexual functioning, sexual pleasure,

and sexual distress were all significantly improved in

the intervention group compared to the control group

(p = 0.031, 0.001, and 0.002, respectively).[18]

Psychological Indications

van den Berg et al[19] examined the efficacy of online

therapy for BCS in the hopes of improving psychological

adjustment. Women were recruited to participate in this

RCT and were randomised either into a control group

(n=80) or an intervention group (n=70). The 16-week

online therapy, called BREATH,[32] used principles of

CBT to create this online self-management intervention

to help participants cope with survivorship (Table 2).

The two primary outcomes were general psychological

distress (tested by the Symptom Checklist 90)[33] and

psychological empowerment (assessed using the Cancer

Empowerment Questionnaire; CEQ).[34] At the baseline

assessment, both groups had similar mean scores on both measures. After controlling for baseline levels

of psychological distress, the intervention group had

significantly less psychological distress than the control

group (p < 0.05). However, while both groups showed a

slight improvement in the CEQ, there was no significant

difference between the scores of the two groups (p =

0.336; value adjusted for the baseline level). One of

the secondary outcomes tested was general negative

adjustment by the Hospital Anxiety and Depression

Scale[35] total score, where lower scores represent

improvement. At baseline, the intervention and control

groups had similar mean scores, while at follow-up,

those in the intervention group had significantly higher

scores than those in the control group when adjusting for

baseline Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale score

(p < 0.05).[19]

Carpenter et al[20] conducted a study looking at the benefit

of an online workbook for stress management levels

in BCS. In total, 132 women agreed to participate in

the study (intervention group: 71; control group: 61).

Inclusion was determined by multiple indications of

distress. This pilot study helped determine the efficacy

of the online workbook Coping with Cancer Workbook,

which teaches participants coping strategies, and

relaxation management strategies through cognitive

and behaviourally based homework. This workbook is

typically completed in 10 weeks (Table 2). Two of the

primary outcomes tested were (1) self-efficacy for coping

with cancer, tested with the Cancer Behavior Inventory

v2.0[36]; and (2) self-efficacy for coping with negative

mood, assessed with the Negative Mood Regulation

Scale.[37] Finding benefit in the cancer experience was a

secondary outcome completed by the Benefit Finding

Scale (BFS).[38] Baseline measures were all reported as a

composite for all participants, regardless of intervention.

At follow-up, there was a significant difference for

self-efficacy for coping with cancer, with an increase

in the intervention group’s mean score compared to the

control group (p = 0.019). At follow-up, individuals in

the intervention group had significantly higher scores

than those in the control group for the Negative Mood

Regulation Scale (p = 0.007). For the BFS, there was no

significant improvement at follow-up for either group.[20]

DISCUSSION

The aim of this review was to assess published clinical

outcomes following online psychotherapy for BCS.

Overall, there were three studies (60%) that focused on

behavioural indications,[16] [17] [18] and two studies (40%) that

focused on psychological indications[19] [20] (Table 2). For the behavioural-based studies, one study treated patients

with insomnia,[16] one study focused on patients with

fatigue,[17] and one study examined sexual dysfunction.[18]

Of the psychological indications, one study focused

on psychological adjustment[19] and the other examined

stress management.[20]

Online interventions generally resulted in favourable

outcomes with a statistically significant reduction in

symptom severity following therapy. Of the 11 primary

outcomes assessed,[16] [17] [18] [19] [20] the scores of the women in the

intervention groups significantly improved on nine

scales, with associated effect sizes of 0.33[19] to 1.10[16] as

measured by Cohen’s d. Indications that improved were

insomnia,[16] sleep quality,[16] fatigue,[17] sexual functioning,[18]

sexual pleasure,[18] sexual distress,[18] general psychological

distress,[19] self-efficacy for coping with cancer,[20] and

self-efficacy for coping with negative mood.[20] One

primary outcome that was not significant was the CEQ,[19]

which measures how efficiently patients can derive

psychological empowerment from their interpersonal

and intrapersonal environments.[34] Also, there were no

differences seen between the control and intervention

groups on the BFS,[20] which evaluates one’s ability to find

positive outcomes from the cancer experience.[38] Among

the four secondary outcomes examined from three

different studies,[16] [17] [19] women in the intervention group

showed significant improvements on all four indications

(fatigue,[16] functional impairment,[17] psychological

distress,[17] and general negative adjustment[19]).

Traditionally, psychotherapies are used to diminish

bothersome symptoms.[39] As was demonstrated, the online

psychotherapies reviewed were able to decrease a variety

of psychosocial and behavioural symptoms. However,

whether this can be translated into clinically significant

outcomes is not well documented, especially since many

of the included scales do not have published estimates of

the minimal patient-important differences. As well, the

non-significant parameters should be investigated. Both

the CEQ and BFS are non-traditional measures, as they

measure strengths rather than weaknesses. It is possible

that there are smaller effect sizes associated with scales

that evaluate strengths, as opposed to those worded with

respect to reduction of symptoms.[19] For example, for

the primary outcomes, of the nine that were statistically

significant, seven dealt with a decrease of symptoms as

opposed to improving strengths.[16] [17] [18] [19]

The question still remains whether online therapy is

more beneficial than in-person therapy for BCS. Women often find face-to-face psychotherapy intimidating when

talking about sexual and intimate problems and are

more likely to opt out of these programmes than if the

psychotherapy is online.[40] Since sexual dysfunction is a

possible lingering symptom in BCS, online therapy may

be a more attractive alternative. In addition, due to the

harsh negative outcomes (e.g., hair loss, disfigurement,

weight loss, etc.) following cancer treatment[11] many

women may feel self-conscious.[18] They also may feel

too unwell to go out of the house to attend therapy,

leaving online therapy as a possible alternative. Overall,

the results indicate that online therapy for a variety of

symptoms in BCS is beneficial. Due to the unique nature

of a survivor’s life, it may even be more desirable than

traditional therapy.

Online therapies have not only been proven effective for

BCS, but also across other cancer populations, including

the reduction of post-traumatic stress symptoms in long-term

survivors of paediatric cancers[41] and the reduction

of psychological distress in men with prostate cancer.[42]

This invites a search for the benefits of online therapy

for other populations, especially given the present need

to physically distance during the coronavirus disease

2019 pandemic. During the pandemic lockdowns, most

in-person therapy services were either not running or

switched to an online format. Online psychotherapy

can alleviate time constraints, increase accessibility to a

more heterogeneous population,[43] reduce the stigma of

seeking therapy, and eliminate other barriers associated

with seeking therapy in person.[10] It is also perceived

as convenient and comfortable both by patients and by

clinicians.[10]

Despite the benefits presented, practical concerns and

challenges exist that hinder its use in routine practice.

First of all, patient privacy and confidentiality must

be considered. As is common practice for therapeutic

interventions, patients disclose personal information

continuously during therapy. Even though privacy

settings can be monitored, and data encryption solutions

can be employed, one needs to be wary that privacy

still cannot completely be guaranteed online.[10] [44] If one

is accessing online therapy to avoid the stigma of face-to-face appointments,[45] this privacy concern may impact

an individual’s decision to complete therapy online and

may prove to be counterintuitive. In addition, online

therapy is only feasible for individuals who can read,

write, and are proficient with technology. Those who

have poor literacy skills will have difficulty grasping

the knowledge that the therapy provides and hence are not likely to benefit from the programme. An individual

with poor technology skills or those from marginalised

backgrounds may not be able to access online therapy.

Certain techniques, such as body focusing, would be more

difficult to apply in the context of an online environment.

Finally, one practical concern may ensue with the use

of online therapy. How can one know whether there

is a congruency between behaviours, cognitions, and

emotions experienced in reality compared with what

the client reports online? It is possible that individuals

may report improvements that are not truly there, and

due to the limited non-verbal cues and facial expressions

from both parties, the therapist may have difficulties

being more certain that their intention was met and that

the client has shown improvements.[10] With the present

pandemic hindering accessibility to in-person services,

both clients and clinicians must carefully weigh the pros

and cons of online therapy to determine their comfort

with the proposed alternative.

Some limitations of the studies included in this review

should be considered. First, given the relatively short

duration of follow-up, compared to the survivorship

journey, it is unclear whether the demonstrated

improvement at post-intervention assessment could

lead to the long-term remission of their psychiatric

co-morbidities and symptoms. It is thus plausible that

women continue to have subclinical symptoms that are

still present or may later recur. The psychotherapies

presented in the review were typically focused on a

specific symptom (e.g., fatigue, sexuality). As such, it is

possible that women enrolled in these programmes had

multiple psychological comorbidities (e.g., as suggested

by Lee et al[12]), some of which were unaddressed by the

specific intervention they were receiving. In the future,

researchers should investigate the potential of a holistic

care approach, focusing on a comprehensive model

of change, as opposed to specific symptomology.[46]

Also, the types of treatments included in the studies

had different treatment protocols, including duration,

number, and type of modules, symptoms addressed, and

extent of therapist-guidance (Table 2). For example,

Abrahams et al[17] began their procedure with three

face-to-face sessions, while the other four studies had

no in-person therapist contact. This makes it difficult

to identify the optimal interventional model through

indirect comparisons across studies. Another limitation

relates to the online nature of the therapy. Based on

literature estimates, most BCS are aged 60 to 75 years.[17]

Across all five studies, the mean age was 51.7 years.[16] [17] [18] [19] [20]

This might suggest that online psychotherapies attract younger women on average and may be less appealing

to or practical for older BCS given the necessity

for technological proficiency. Moreover, it is well-established

that individuals with higher socioeconomic

status have better overall health.[30] Since individuals of

high SES are more likely to have access to technology

and have superior health outcomes than those of low

socioeconomic status, this might overestimate the true

efficacy of online psychotherapy treatments.[47]

Alongside the limitations of the studies included in this

review, there are also limitations of the present study.

Only RCTs were included in this paper. Although

this improved the internal validity of the study, while

decreasing the effects of confounding, this has the

potential to limit generalisability. As described above, this

review is heterogenous, including studies with diverse

treatment protocols (e.g., session duration) and varying

indicators. Although this may serve as a benefit for some

studies, due to the small number of studies included in

this review, it is more of a hinderance. The heterogeneity

of the studies, combined with a small sample size, yields a

review paper that must be interpreted with caution. These

two limitations are reflective of the lack of literature on

the topic. Future studies should continue to investigate

the efficacy of online therapy for BCS who are struggling

with behavioural, psychological, or social symptoms.

Once enough studies are compiled, it is suggested that

larger reviews and/or meta-analyses are conducted. By

conducting these larger reviews, future research will be

able to make better sense of the outcomes, without being

swayed by high variability.

CONCLUSION

Individuals who have recovered from breast cancer often

have residual behavioural, physical, or social symptoms

from the cancer experience.[12] Due to these problems,

BCS may be a population that may particularly benefit

from online psychotherapy. The purpose of this review

was to investigate whether online psychotherapy is

effective for the behavioural and psychological sequelae

of BCS. This study found support for improving

behavioural (e.g., insomnia) and psychological (e.g.,

stress management) symptomology using an online

psychotherapeutic paradigm.[16] [17] [18] [19] [20] All five studies

included in the review were based on CBT, suggesting

that this type of therapy may be particularly useful

within the BCS population. Although the conclusions

of this review are encouraging, limitations must be

considered. This review is highly heterogenous and

has a small sample size. As such, the generalisability of this study may be limited. More controlled research

must be done in this setting. Once enough literature

exists, researchers are encouraged to evaluate the studies

comprehensively using meta-analytic or other systematic

review methodologies.

REFERENCES

1. Cuijpers P, Karyotaki E, Reijnders M, Huibers MJ. Who benefits from psychotherapies for adult depression? A meta-analytic update of the evidence. Cogn Behav Ther. 2018;47:91-106. Crossref

2. Barth J, Munder T, Gerger H, Nüesch E, Trelle S, Znoj H, et al.

Comparative efficacy of seven psychotherapeutic interventions

for patients with depression: a network meta-analysis. PLoS Med.

2013;10:e1001454. Crossref

3. Smith GC. Psychotherapy. In: Fink G, editor. Encyclopedia of

Stress. 2nd ed. Amsterdam: Elsevier Press; 2007. p 302-7. Crossref

4. Cuijpers P, Andersson G, Donker T, van Straten A. Psychological

treatment of depression: results of a series of meta-analyses. Nord

J Psychiatry. 2011;65:354-64. Crossref

5. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer

J Clin. 2019;69:7-34. Crossref

6. Saeedi B, Khoshnood Z, Dehghan M, Abazari F, Saeedi A. The

effect of positive psychotherapy on the meaning of life in patients

with cancer: a randomized clinical trial. Indian J Palliat Care.

2019;25:210-7. Crossref

7. van Eenbergen MC, van den Hurk C, Mols F, van de Poll-Franse LV.

Usability of an online application for reporting the burden of side

effects in cancer patients. Support Care Cancer. 2019;27:3411-9. Crossref

8. Breitbart W, Pessin H, Rosenfeld B, Applebaum AJ, Lichtenthal

WG, Li Y, et al. Individual meaning-centered psychotherapy

for the treatment of psychological and existential distress: a

randomized controlled trial in patients with advanced cancer.

Cancer. 2018;124:3231-9. Crossref

9. Chakrabarti S. Usefulness of telepsychiatry: a critical evaluation

of videoconferencing-based approaches. World J Psychiatry.

2015;5:286-304 Crossref

10. Stoll J, Müller JA, Trachsel M. Ethical issues in online

psychotherapy: a narrative review. Front Psychiatry. 2020;10:993. Crossref

11. Cheung EO, Cohn MA, Dunn LB, Melisko ME, Morgan S,

Penedo FJ, et al. A randomized pilot trial of a positive affect skill

intervention (lessons in linking affect and coping) for women with

metastatic breast cancer. Psychooncology. 2017;26:2101-8. Crossref

12. Lee L, Ross A, Griffith K, Jensen RE, Wallen GR. Symptom

clusters in breast cancer survivors: a latent class profile analysis.

Oncol Nurs Forum. 2020;47:89-100. Crossref

13. Mitchell AJ. New developments in the detection and treatment of

depression in cancer settings. Prog Neurol Psychiatry. 2011;15:12-20. Crossref

14. Semin JN, Palm D, Smith LM, Ruttle S. Understanding breast

cancer survivors’ financial burden and distress after financial

assistance. Support Care Cancer. 2020;28:4241-8. Crossref

15. Simard S, Thewes B, Humphris G, Dixon M, Hayden C,

Mireskandari S, et al. Fear of cancer recurrence in adult cancer

survivors: a systematic review of quantitative studies. J Cancer

Surviv. 2013;7:300-22. Crossref

16. Zachariae R, Amidi A, Damholdt MF, Clausen CD, Dahlgaard J,

Lord H, et al. Internet-delivered cognitive-behavioral therapy for

insomnia in breast cancer survivors: a randomized controlled trial.

J Natl Cancer Inst. 2018;110:880-7. Crossref

17. Abrahams HJ, Gielissen MF, Donders RR, Goedendorp MM,

van der Wouw AJ, Verhagen CA, et al. The efficacy of internet-based

cognitive behavioral therapy for severely fatigued survivors of breast cancer compared with care as usual: a randomized

controlled trial. Cancer. 2017;123:3825-34. Crossref

18. Hummel SB, van Lankveld JJ, Oldenburg HS, Hahn DE,

Kieffer JM, Gerritsma MA, et al. Efficacy of internet-based

cognitive behavioral therapy in improving sexual functioning of

breast cancer survivors: results of a randomized controlled trial. J

Clin Oncol. 2017;35:1328-40. Crossref

19. van den Berg SW, Gielissen MF, Custers JA, van der Graaf WT,

Ottevanger PB, Prins JB. BREATH: web-based self-management

for psychological adjustment after primary breast cancer-results

of a multicenter randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol.

2015;33:2763-71. Crossref

20. Carpenter KM, Stoner SA, Schmitz K, McGregor BA, Doorenbos AZ. An online stress management workbook for breast

cancer. J Behav Med. 2014;37:458-68. Crossref

21. Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The

Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric

practice and research. Psych Res. 1989;28:193-213. Crossref

22. Ritterband LM, Bailey ET, Thorndike FP, Lord HR,

Farrell-Carnahan L, Baum LD. Initial evaluation of an Internet

intervention to improve the sleep of cancer survivors with insomnia.

Psychooncology. 2012;21:695-705. Crossref

23. Bastien CH, Vallieres A, Morin CM. Validation of the Insomnia

Severity Index as an outcome measure for insomnia research. Sleep

Med. 2001;2:297-307. Crossref

24. Yellen SB, Cella DF, Webster K, Blendowski C, Kaplan E.

Measuring fatigue and other anemia-related symptoms with the

Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy (FACT) measurement

system. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1997;13:63-74. Crossref

25. Vercoulen J, Alberts M, Bleijenberg G. De Checklist Individual

Strength (CIS) [in Dutch]. Gedragstherapie. 1999;32:131-6.

26. Bergner M, Bobbitt RA, Carter WB, Gilson BS. The Sickness

Impact Profile: development and final revision of a health status

measure. Med Care. 1981;19:787-805. Crossref

27. Derogatis LR. BSI 18, Brief Symptom Inventory 18: Administration,

Scoring and Procedures Manual. NCS Pearson, Inc.; 2001. Crossref

28. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical

Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-IV-TR. Washington D.C.:

American Psychiatric Association; 2011.

29. Rosen R, Brown C, Heiman J, Leiblum S, Meston C, Shabsigh R,

et al. The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI): a multidimensional

self-report instrument for the assessment of female sexual function.

J Sex Marital Ther. 2000;26:191-208. Crossref

30. Thirlaway K, Fallowfield L, Cuzick J. The Sexual Activity

Questionnaire: a measure of women’s sexual functioning. Qual

Life Res. 1996;5:81-90. Crossref

31. Derogatis LR, Rosen R, Leiblum S, Burnett A, Heiman J. The

Female Sexual Distress Scale (FSDS): Initial validation of a

standardized scale for assessment of sexually related personal

distress in women. J Sex Marital Ther. 2002;28:317-30. Crossref

32. van den Berg SW, Gielissen MF, Ottevanger PB, Prins JB.

Rationale of the BREAst cancer e-healTH (BREATH) multicentre

randomised controlled trial: an internet-based self-management

intervention to foster adjustment after curative breast cancer by

decreasing distress and increasing empowerment. BMC Cancer.

2012;12:394. Crossref

33. Schauenburg H, Strack M. Measuring psychotherapeutic change

with the symptom checklist SCL 90 R. Psychother Psychosom.

1999;68:199-206. Crossref

34. van den Berg SW, van Amstel FK, Ottevanger PB, Gielissen MF,

Prins JB. The Cancer Empowerment Questionnaire: Psychological

empowerment in breast cancer survivors. J Psychosoc Oncol.

2013;31:565-83. Crossref

35. Vodermaier A, Millman RD. Accuracy of the Hospital Anxiety and

Depression Scale as a screening tool in cancer patients: a systematic

review and meta-analysis. Support Care Cancer. 2011;19:1899-908. Crossref

36. Merluzzi TV, Nairn RC, Hegde K, Martinez Sanchez MA, Dunn L.

Self-efficacy for coping with cancer: revision of the Cancer

Behavior Inventory (version 2.0). Psychooncology. 2001;10:206-17. Crossref

37. Catanzaro SJ, Mearns J. Measuring generalized expectancies

for negative mood regulation: initial scale development and

implications. J Pers Assess. 1990;54:546-63. Crossref

38. Carver CS, Antoni MH. Finding benefit in breast cancer during the

year after diagnosis predicts better adjustment 5 to 8 years after

diagnosis. Health Psychology. 2004;23:595-8. Crossref

39. Priebe S, Omer S, Giacco D, Slade M. Resource-oriented therapeutic models in psychiatry: conceptual review. Br J Psychiatry. 2014;204:256-61. Crossref

40. Hummel SB, van Lankveld JJ, Oldenburg HS, Hahn DE,

Broomans E, Aaronson NK. Internet-based cognitive behavioral

therapy for sexual dysfunctions in women treated for breast cancer:

design of a multicenter, randomized controlled trial. BMC Cancer.

2015;15:321. Crossref

41. Seitz DC, Knaevelsrud C, Duran G, Waadt S, Loos S, Goldbeck L. Efficacy of an internet-based cognitive-behavioral intervention for

long-term survivors of pediatric cancer: a pilot study. Support Care

Cancer. 2014;22:2075-83. Crossref

42. Wootten AC, Abbott JA, Meyer D, Chisholm K, Austin DW,

Klein B, et al. Preliminary results of a randomised controlled trial

of an online psychological intervention to reduce distress in men

treated for localised prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2015;68:471-9. Crossref

43. Cartreine JA, Ahern DK, Locke SE. A roadmap to computer-based

psychotherapy in the United States. Harv Rev Psychiatry.

2010;18:80-95. Crossref

44. Taylor CB, Luce KH. Computer- and internet-based psychotherapy

interventions. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2003;12:18-22. Crossref

45. Thomas A, Grandner M, Nowakowski S, Nesom G, Corbitt C,

Perlis ML. Where are the behavioral sleep medicine providers and

where are they needed? A geographic assessment. Behav Sleep

Med. 2016;14:687-98. Crossref

46. Zamanzadeh V, Jasemi M, Valizadeh L, Keogh B, Taleghani F.

Effective factors in providing holistic care: a qualitative study.

Indian J Palliat Care. 2015;21:214-24. Crossref

47. Adler NE, Snibbe AC. The role of psychosocial processes in

explaining the gradient between socioeconomic status and health.

Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2003;12:119-23. Crossref