Breast Manifestations in Patients with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Breast Manifestations in Patients with Systemic Lupus

Erythematosus

DLY Chow1, T Wong2, CM Chau2, RLS Chan2, TS Chan2, DCY Lui2, AWT Yung2, ASL Fung1,

JKF Ma2

1 Department of Radiology and Nuclear Medicine, Tuen Mun Hospital, Hong Kong

2 Department of Radiology, Princess Margaret Hospital, Hong Kong

Correspondence: Dr DLY Chow, Department of Radiology, Tuen Mun Hospital, Hong Kong. Email: deniselychow@gmail.com

Submitted: 10 Mar 2020; Accepted: 4 Jun 2020.

Contributors: DLYC, TW and CMC designed the study and acquired the data. DLYC and TW analysed the data. DLYC drafted the manuscript.

TW, CMC, RLSC, TSC, DCYL, AWTY, ASLF and JKFM critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content.

Conflicts of Interest: authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Funding/Support: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data Availability: All data generated or analysed during the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: This research was approved by the Kowloon West Cluster Research Ethics Committee (Ref KW/EX-20-008(143-08)) and New

Territories West Cluster Research Ethics Committee (Ref NTWC/REC/19130). Patient consent was waived by the ethics board (KW/EX-20-008(143-08) and NTWC/REC/19130).

Abstract

Objectives

Breast manifestations in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) include primary lupus of the

breast (i.e., lupus mastitis) and secondary manifestations of lupus such as lymphadenopathy or vascular calcifications.

To clarify the spectrum of breast manifestations in patients with SLE, we reviewed the clinical, imaging, and

pathological manifestations of breast diseases in SLE patients.

Methods

We retrospectively reviewed cases of SLE patients with breast imaging performed in five centres from

January 2010 to April 2020. Patient demographics, breast symptoms, imaging, and pathological findings, and their

subsequent management, were reviewed.

Results

A total of 16 cases were included. The mean follow-up period was 61 months. A palpable breast mass was

the most frequent clinical presentation, followed by mastalgia and axillary swelling. A wide range of imaging findings

was encountered on ultrasonography and/or mammography, including extensive calcifications in both breasts, breast

masses with features suspicious for malignancy, fat necrosis, oedema, arterial calcifications, architectural distortion,

and axillary lymphadenopathy. Two cases of lupus mastitis and a case of invasive ductal carcinoma were identified.

Conclusion

No definite distinguishing features between lupus mastitis and breast malignancy were observed

on imaging. Pathological correlation is recommended when imaging features suspicious for malignancy are

demonstrated.

Key Words: Lupus erythematosus, systemic; Magnetic resonance imaging; Mammography; Mastitis; Ultrasonography

中文摘要

系統性紅斑狼瘡患者的乳腺表現

周朗妍、黃婷、周智敏、陳樂詩、陳庭笙、雷彩如、翁維德、馮小玲、馬嘉輝

目的

系統性紅斑狼瘡(SLE)患者的乳腺表現包括乳腺原發性狼瘡(即狼瘡性乳腺炎)和狼瘡的繼發性表現,例如淋巴結腫大或血管鈣化。為了闡明SLE患者的各種乳腺表現,本研究回顧SLE患者乳腺疾病的臨床、影像學和病理學表現。

方法

回顧性分析2010年1月至2020年4月期間在五間醫療中心進行乳腺成像的SLE患者病例。回顧患者的人口統計學、乳腺症狀、影像學和病理學及其後續處理。

結果

共納入16例。平均隨訪期為61個月。最常見的臨床表現是可觸及的乳腺腫塊,其次是乳腺痛和腋窩腫脹。在超聲檢查和/或乳腺X光檢查中發現各種影像學表現,包括雙側乳腺廣泛鈣化、乳腺腫塊具可疑惡性腫瘤特徵、脂肪壞死、水腫、動脈鈣化、結構變形和腋窩淋巴結腫大。病例中有2例狼瘡性乳腺炎和1例浸潤性導管癌。

結論

影像學上未觀察到狼瘡性乳腺炎與乳腺惡性腫瘤之間的明確區分特徵。 當發現可疑惡性腫瘤的影像特徵時,建議進行病理學相關檢查。

INTRODUCTION

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a complex

autoimmune disease with multisystem involvement

characterised by inflammation, vasculitis, immune

complex deposition, and vasculopathy.[1] It is substantially

more common in women of childbearing age.[2] Breast

diseases in patients with lupus may be primary

lupus of the breast (i.e., lupus mastitis) or secondary

manifestations of lupus such as lymphadenopathy or

vascular calcifications. These patients are also subject

to breast diseases unrelated to SLE. To our knowledge,

the spectrum of breast manifestations in patients with

SLE has not been described in the literature, with case

reports mainly focusing on lupus mastitis. To clarify the

spectrum of breast manifestations in patients with SLE,

we retrospectively reviewed the clinical, imaging, and

pathological findings in patients with SLE.

METHODS

Cases of SLE with breast imaging (mammography,

ultrasound, or magnetic resonance imaging [MRI])

in five centres from January 2010 to April 2020 were

identified through a search of the Radiology Information

System using the keywords ‘lupus’, ‘SLE’, and ‘systemic

lupus erythematosus’. Cases without breast imaging or

with unavailable imaging were excluded.

Sixteen cases were found; all had available breast imaging studies. Case demographics, breast symptoms,

breast imaging findings, pathological findings (if any)

and subsequent management were reviewed.

RESULTS

Patient Demographics

In total, 16 cases of SLE were identified and included

for analysis. No cases were excluded. The mean age of

presentation of breast symptoms was 44 years (range,

23-71). The mean duration of SLE at time of breast

disease presentation was 11.2 years. Breast symptoms

occurred after diagnosis of SLE in 14 of the 16 cases.

Breast symptoms occurred before diagnosis of SLE in

the remaining two cases, and among them one presented

with a breast mass 2 years before the diagnosis of SLE.

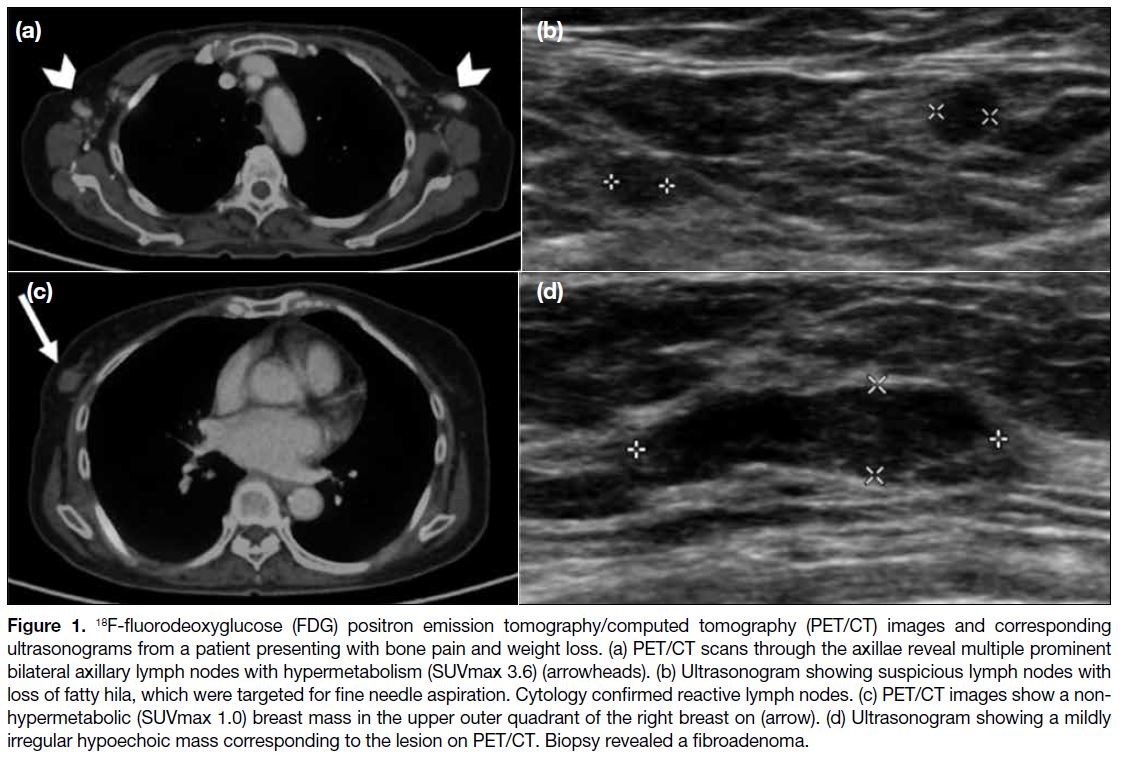

One patient presented with bone pain and weight loss,

and breast imaging was performed at the same time as

part of the systemic investigation for SLE (Figure 1).

The mean follow-up period was 61 months.

Figure 1. 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) images and corresponding

ultrasonograms from a patient presenting with bone pain and weight loss. (a) PET/CT scans through the axillae reveal multiple prominent

bilateral axillary lymph nodes with hypermetabolism (SUVmax 3.6) (arrowheads). (b) Ultrasonogram showing suspicious lymph nodes with

loss of fatty hila, which were targeted for fine needle aspiration. Cytology confirmed reactive lymph nodes. (c) PET/CT images show a non-hypermetabolic

(SUVmax 1.0) breast mass in the upper outer quadrant of the right breast on (arrow). (d) Ultrasonogram showing a mildly

irregular hypoechoic mass corresponding to the lesion on PET/CT. Biopsy revealed a fibroadenoma.

Clinical Presentation

Among the 16 patients, palpable breast mass was the

most common clinical presentation in nine (56%)

patients, followed by mastalgia in three (19%) patients

and axillary swelling in two (13%) patients. One (6%)

patient presented with a palpable breast mass and axillary

swelling, and one (6%) patient presented with bone pain

and weight loss.

Investigations

One (6%) patient underwent mammography,

ultrasonography, and MRI scans, eight (50%) patients

underwent mammography and ultrasonography, six

(38%) patients underwent ultrasonography only, and the

remaining one (6%) patient underwent mammography

only. In total, ultrasonography of the breasts was

performed in 15 (94%) of the 16 cases.

Imaging Findings

Imaging findings included breast mass, calcifications,

fat necrosis, architectural distortion, breast oedema, and

axillary lymphadenopathy (Table).

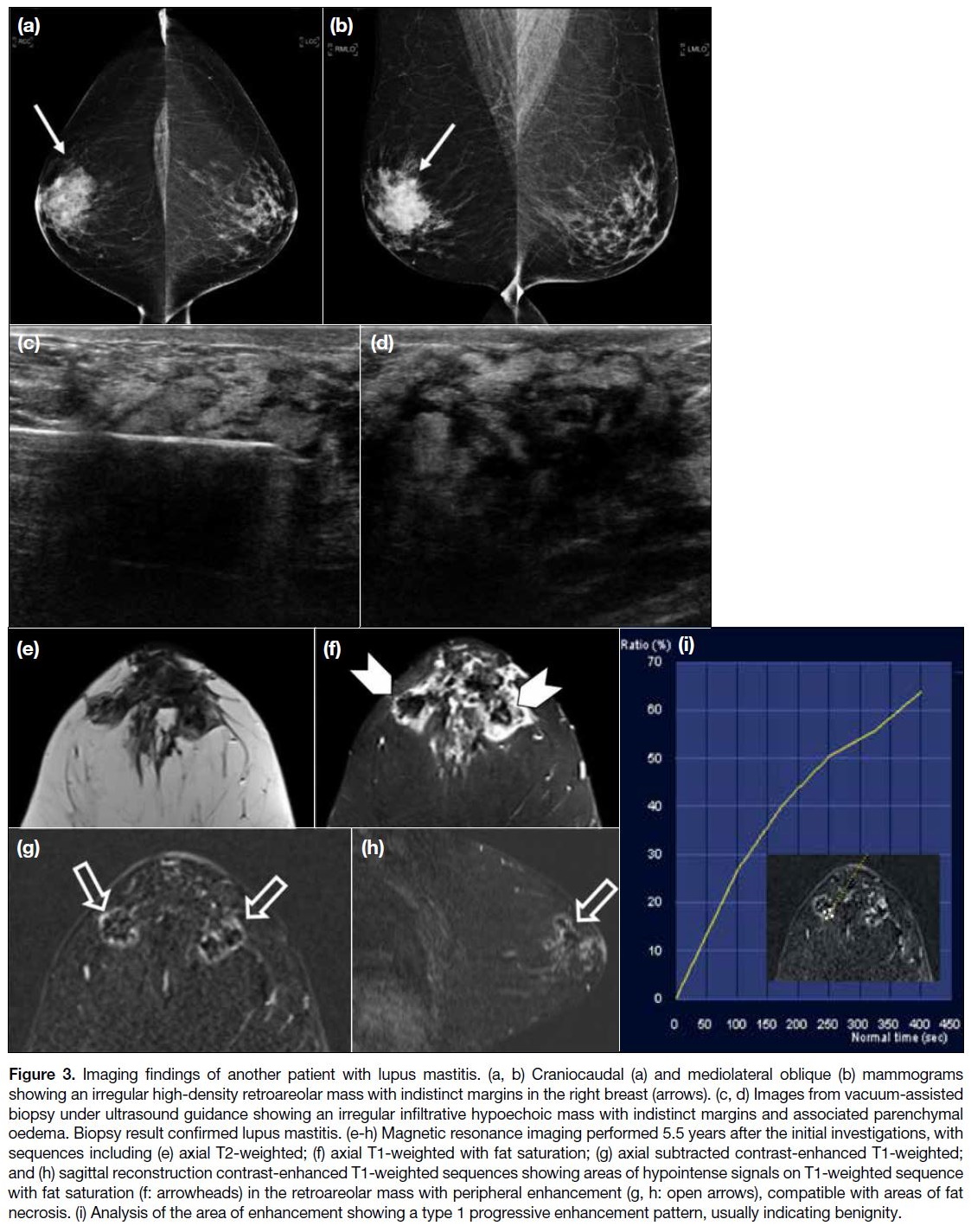

Table. Imaging findings.

Lupus Mastitis

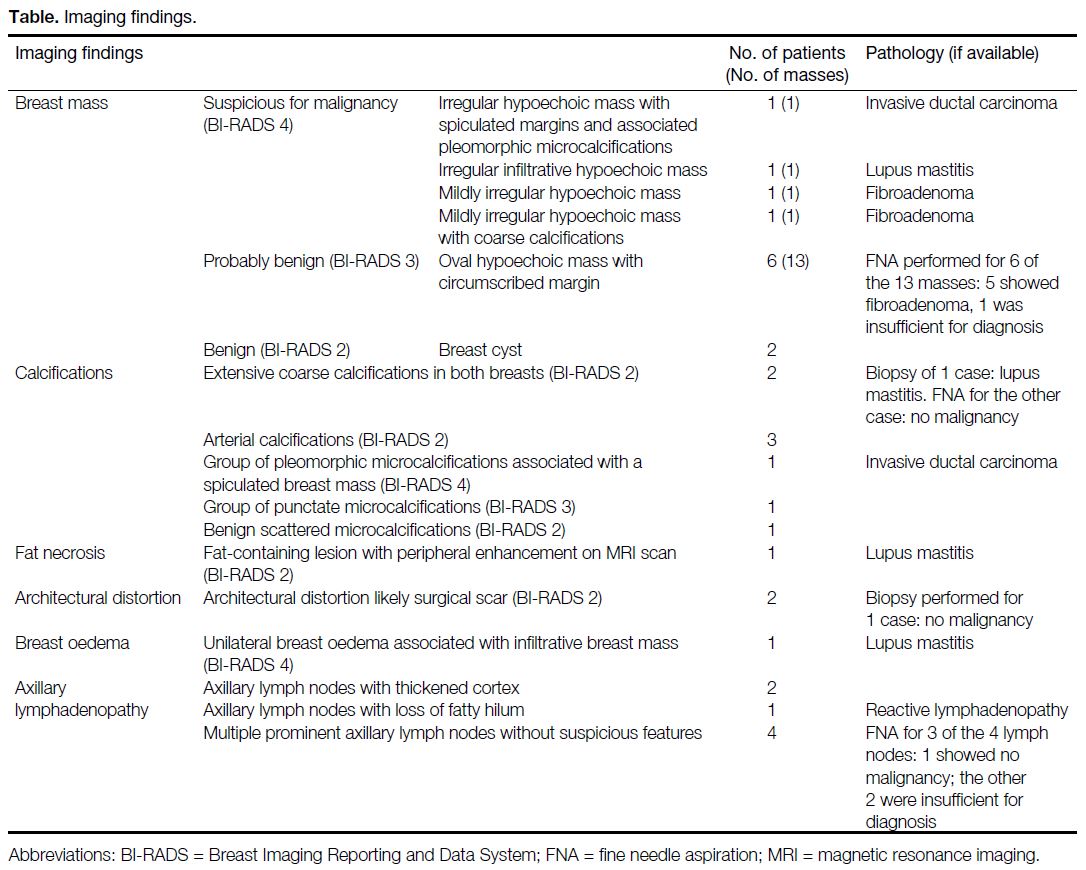

There were two cases of lupus mastitis with pathological

confirmation. Both patients presented with a palpable

breast mass. In the first case, extensive calcifications

were seen both on mammography and ultrasound and

the patient subsequently underwent core biopsy (Figure 2). Pathology showed hyaline fat necrosis, nodular

perilobular and perivascular inflammatory infiltrate

comprising lymphocytes and plasma cells, and stromal fibrosis with microcalcifications, compatible with lupus

mastitis. The patient was treated with systemic steroids

and immunosuppressants as part of her therapy for

SLE. During >6 years of clinical and imaging follow-up

examinations, the calcifications remained stable and

the patient did not have recurrence of lupus mastitis

symptoms. No further biopsy was performed.

Figure 2. Imaging findings of a

patient with lupus mastitis. (a, b)

Craniocaudal (a) and mediolateral

oblique (b) mammograms showing

extensive coarse calcifications of

both breasts. (c) Ultrasonogram

showing diffuse coarse

calcifications of both breasts.

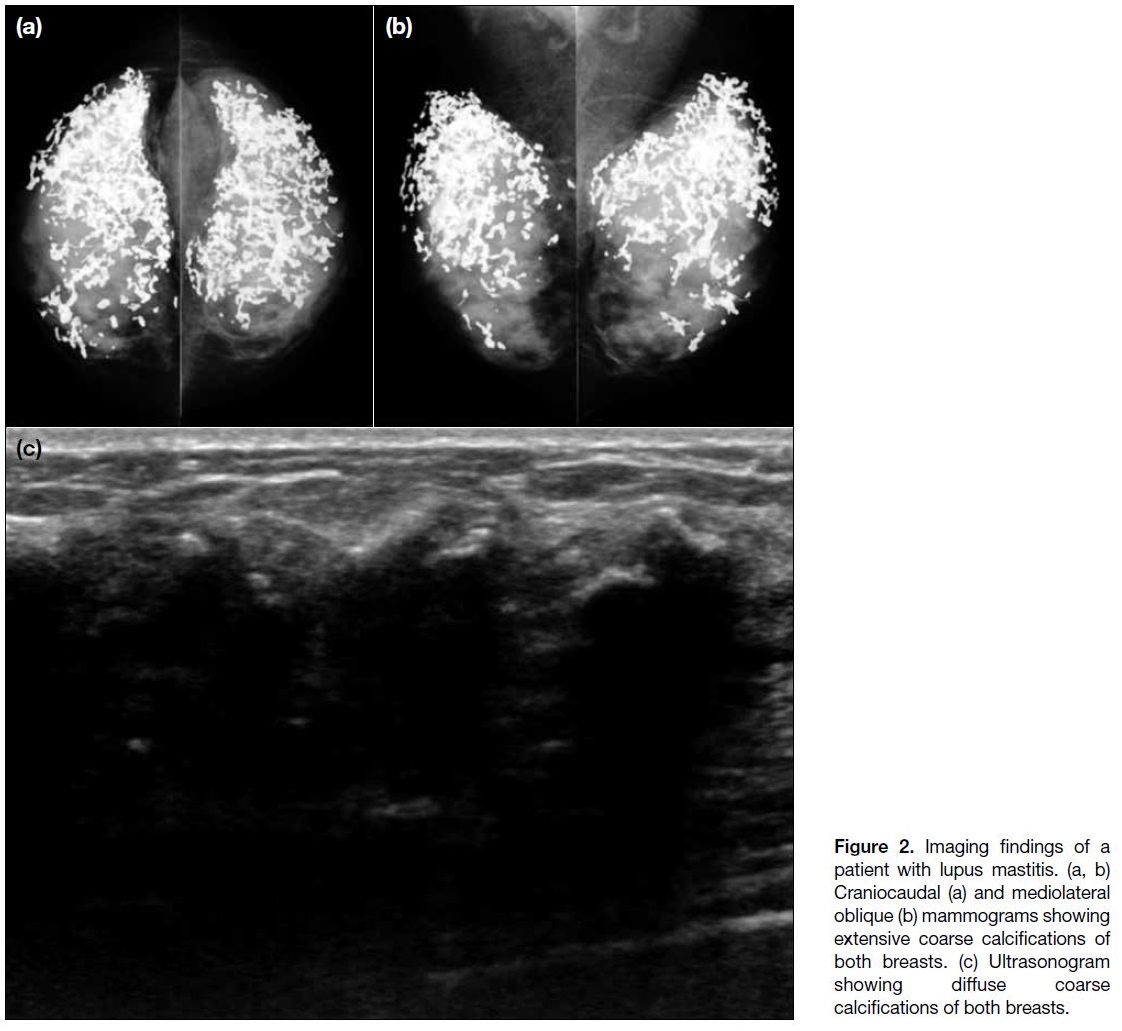

In the second case (Figure 3), an irregular high-density

retroareolar mass with indistinct margins was

present in the right breast on mammography, with

ultrasound showing a corresponding irregular infiltrative

hypoechoic mass with associated parenchymal oedema.

It was classified as highly suspicious for malignancy.

Vacuum-assisted biopsy was performed in this case with

pathology confirming lupus mastitis.

Figure 3. Imaging findings of another patient with lupus mastitis. (a, b) Craniocaudal (a) and mediolateral oblique (b) mammograms

showing an irregular high-density retroareolar mass with indistinct margins in the right breast (arrows). (c, d) Images from vacuum-assisted

biopsy under ultrasound guidance showing an irregular infiltrative hypoechoic mass with indistinct margins and associated parenchymal

oedema. Biopsy result confirmed lupus mastitis. (e-h) Magnetic resonance imaging performed 5.5 years after the initial investigations, with

sequences including (e) axial T2-weighted; (f) axial T1-weighted with fat saturation; (g) axial subtracted contrast-enhanced T1-weighted;

and (h) sagittal reconstruction contrast-enhanced T1-weighted sequences showing areas of hypointense signals on T1-weighted sequence

with fat saturation (f: arrowheads) in the retroareolar mass with peripheral enhancement (g, h: open arrows), compatible with areas of fat

necrosis. (i) Analysis of the area of enhancement showing a type 1 progressive enhancement pattern, usually indicating benignity.

Ultrasound and MRI scans were performed 5.5 years

later in view of persistent breast symptoms. MRI

scans showed a heterogeneous retroareolar mass on

T2-weighted images with associated skin thickening

and mild breast oedema, which was proven to be lupus

mastitis on previous biopsy. Areas of signal suppression with peripheral enhancement within the mass on the T1-weighted fat-saturated sequence were suggestive of fat

necrosis, compatible with the pathological process of

lupus panniculitis. The peripheral enhancement showed

a progressive enhancement pattern suggestive of a type

1 kinetic curve.[3] Ultrasound findings were static, and the

patient remained stable with medical therapy of SLE.

Breast Mass with Suspicious Imaging Features for

Malignancy

Apart from the previously mentioned cases of

pathologically confirmed lupus mastitis, there were three

other breast masses with suspicious imaging features

for malignancy in our patient cohort. One of them was

proven to be invasive ductal carcinoma, while the other

two were fibroadenomas.

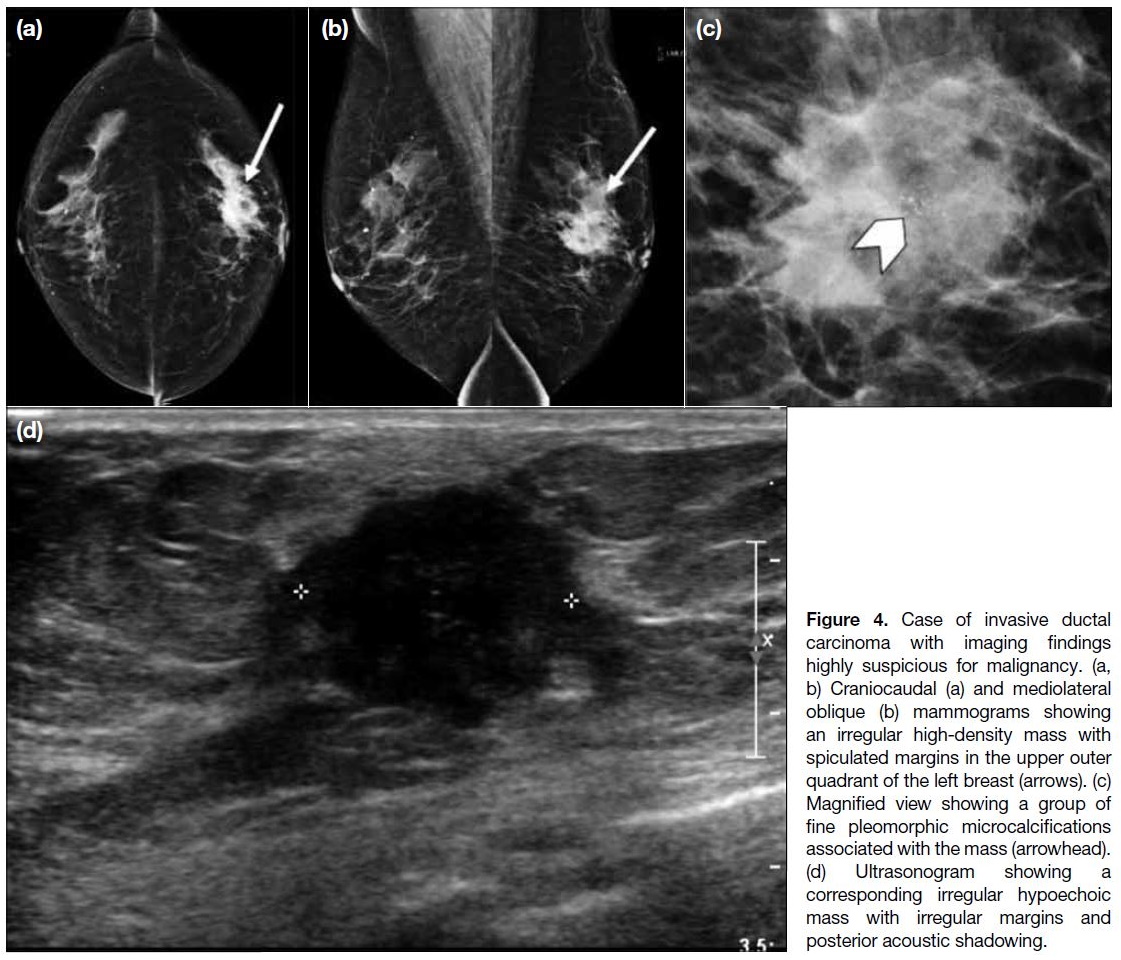

The invasive ductal carcinoma (Figure 4) was highly suspicious for malignancy (Breast Imaging Reporting

and Data System [BI-RADS] 4C) on imaging. On

mammography, there was a spiculated mass with

associated fine pleomorphic microcalcifications. On

ultrasonography, a corresponding irregular hypoechoic

mass with spiculated margin and posterior acoustic

shadowing was detected. Core biopsy was performed

and yielded invasive ductal carcinoma. The patient

subsequently underwent mastectomy and axillary

dissection with adjuvant chemotherapy.

Figure 4. Case of invasive ductal

carcinoma with imaging findings

highly suspicious for malignancy. (a,

b) Craniocaudal (a) and mediolateral

oblique (b) mammograms showing

an irregular high-density mass with

spiculated margins in the upper outer

quadrant of the left breast (arrows). (c)

Magnified view showing a group of

fine pleomorphic microcalcifications

associated with the mass (arrowhead).

(d) Ultrasonogram showing a

corresponding irregular hypoechoic

mass with irregular margins and

posterior acoustic shadowing.

The fibroadenomas were slightly irregular masses with

and without internal coarse calcifications.

Probably Benign Oval Circumscribed Hypoechoic

Breast Masses

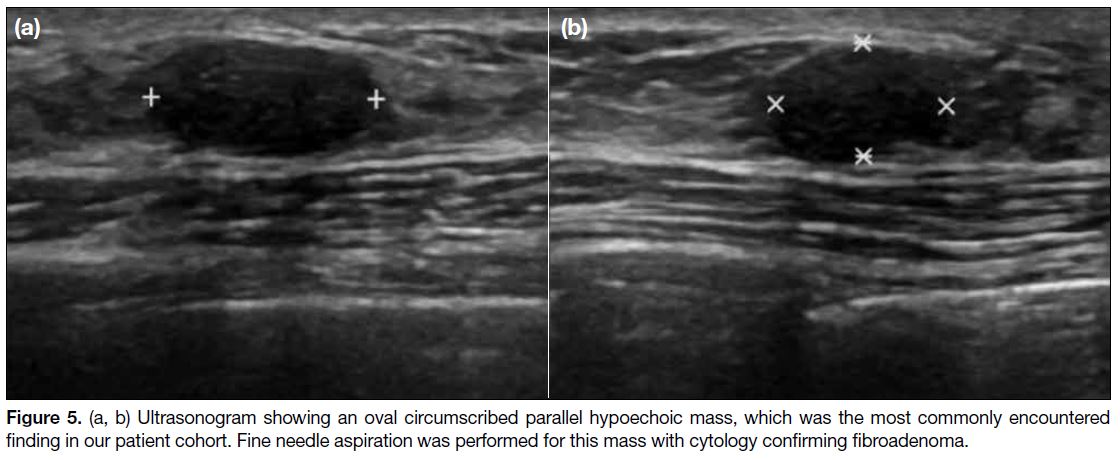

Oval circumscribed hypoechoic masses on

ultrasonography, which were classified as probably benign (BI-RADS 3), were the most commonly

encountered breast manifestation in our cases, with

13 masses observed in six of the patients (Figure 5). Fine

needle aspiration (FNA) was performed for six of these

13 masses, yielding fibroadenoma for five of the cases.

One of these masses showed mild interval enlargement

on new ultrasonography at 6 months; results of a new core

biopsy showed no malignancy. The remaining one case

with FNA performed showed inconclusive results as the

FNA sample was insufficient for diagnosis; this patient

was followed up clinically and with breast ultrasound

for >3 years, showing stability of the oval hypoechoic masses. All of the 13 oval circumscribed hypoechoic

masses were followed up with breast imaging, with the

exception of the aforementioned mass that showed mild

interval enlargement, the other 12 masses all showed

stability with range of follow-up period from 3.5 years to

7 years, thus classified as benign.

Figure 5. (a, b) Ultrasonogram showing an oval circumscribed parallel hypoechoic mass, which was the most commonly encountered

finding in our patient cohort. Fine needle aspiration was performed for this mass with cytology confirming fibroadenoma.

Calcifications

We encountered two cases of extensive calcifications in

both breasts; one was the case of lupus mastitis (Figure 2)

described above, while the other case showed no

malignancy by FNA.

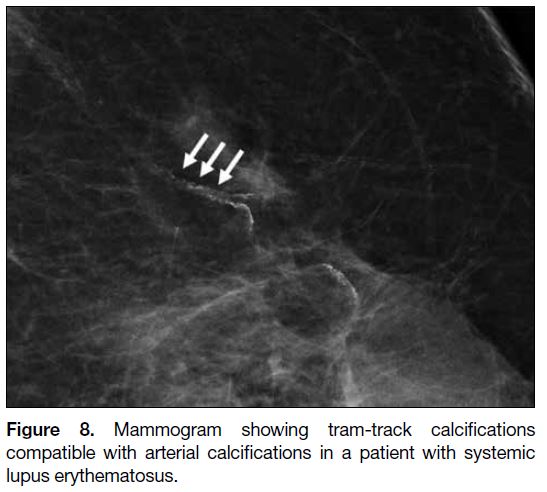

Arterial calcifications were observed in three patients.

All three patients had a history of lupus nephritis.

Two of them did not have traditional risk factors for

atherosclerosis, namely hypertension, diabetes mellitus,

hyperlipidaemia and obesity, while the other patient had

hyperlipidaemia but not known of diabetes mellitus or

hypertension.

Other calcifications observed in our patients included

groups of fine pleomorphic microcalcifications in

association with a spiculated breast mass in the case of

invasive ductal carcinoma (Figure 4), a group of punctate

microcalcifications that was stable on follow-up, and

benign scattered microcalcifications.

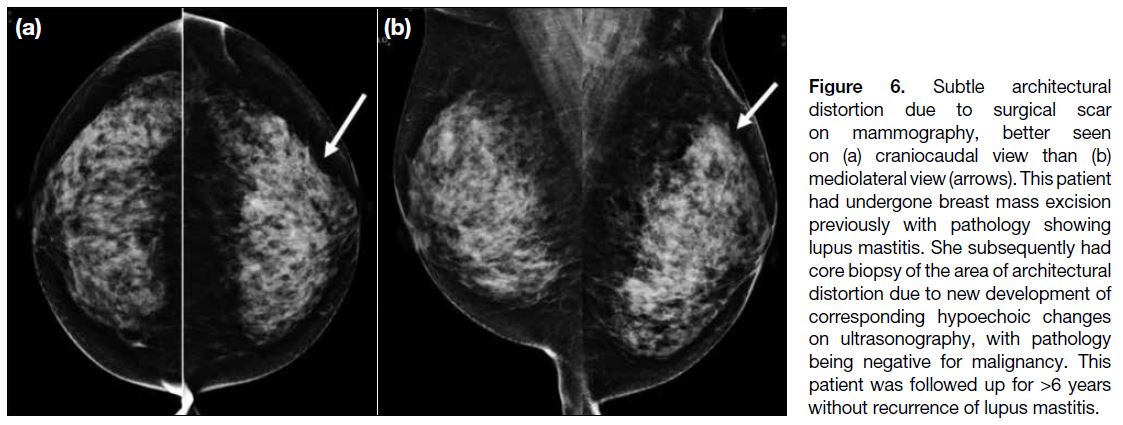

Architectural Distortion

Architectural distortion was observed in two of the cases

and was likely due to scar related to previous breast

surgery. One of the patients had a history of excision of

phyllodes tumour and fibroadenoma. The other patient

(Figure 6) had undergone previous breast mass excision

with pathology showing lupus mastitis. This patient

subsequently had core biopsy due to new development

of subtle hypoechoic changes on ultrasonography, which

corresponded to the site of architectural distortion, with

pathology being negative for malignancy. This patient

was followed up for 6 years with stable imaging results

and without recurrence of breast symptoms suggestive

of lupus mastitis.

Figure 6. Subtle architectural

distortion due to surgical scar

on mammography, better seen

on (a) craniocaudal view than (b)

mediolateral view (arrows). This patient

had undergone breast mass excision

previously with pathology showing

lupus mastitis. She subsequently had

core biopsy of the area of architectural

distortion due to new development of

corresponding hypoechoic changes

on ultrasonography, with pathology

being negative for malignancy. This

patient was followed up for >6 years

without recurrence of lupus mastitis.

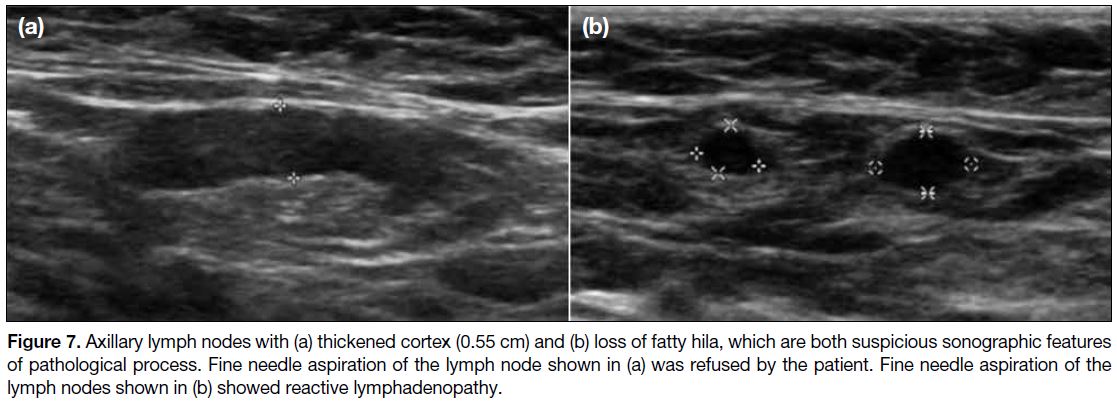

Axillary Lymphadenopathy

Axillary lymph nodes with suspicious features such as

thickened cortex and/or loss of fatty hila were present in

three patients (Figure 7). FNA was performed for one

patient with cytology being reactive lymphadenopathy.

FNA was not performed for the other two cases with

suspicious axillary lymph nodes as the patient refused

for one case and clinical features were not suspicious for

the other case. Multiple axillary lymph nodes without

suspicious imaging features were observed in four

patients. Three patients underwent FNA of lymph nodes

with one of them showing no evidence for malignancy,

while the other two samples were insufficient for

diagnosis. All of the cases, including those with suspicious features, showed stability on follow-up

ultrasound with follow-up period of 15 months to 8

years.

Figure 7. Axillary lymph nodes with (a) thickened cortex (0.55 cm) and (b) loss of fatty hila, which are both suspicious sonographic features

of pathological process. Fine needle aspiration of the lymph node shown in (a) was refused by the patient. Fine needle aspiration of the

lymph nodes shown in (b) showed reactive lymphadenopathy.

DISCUSSION

Our review showed that a wide spectrum of generally

nonspecific sonographic and mammographic findings

can be present in patients with SLE. Some are due to

SLE, including primary lupus of the breast (i.e., lupus

mastitis) and secondary manifestations of SLE such

as lymphadenopathy or vascular calcifications. Other

findings, such as breast cancer, are not known to be

lupus-related and can occur in women unaffected by

lupus.

Lupus Mastitis

Lupus mastitis is a subset of lupus panniculitis that is

localised to the breast and is a rare manifestation of

SLE. Lupus panniculitis is a rare chronic inflammatory

reaction of the subcutaneous fat that can occur in 2% to

3% of patients with SLE, usually between age 20 and

50 years, and more common in women than in men.[4] [5] [6]

Clinically, lupus mastitis can occur in patients with an

established diagnosis of SLE or can rarely be the first

manifestation of the disease.[5] In both cases of lupus

mastitis in our cohort, SLE was established before the

onset of breast symptoms. The most common presentation

is a palpable lesion, often associated with pain,[7] as in

both of our cases. The overlying skin may be normal

but cutaneous changes such as erythema, hyperkeratosis,

lipoatrophy or even ulceration can be evident.[5] Diffuse

breast enlargement and palpable axillary lymph nodes

are less common.[7] The clinical course of lupus mastitis

is often chronic with flares and remissions.[6]

For histopathological diagnosis, the major criteria are fat

hyaline necrosis, lymphocytic infiltration with lymphoid

nodules surrounding the necrosis, periseptal or lobular

panniculitis, and microcalcifications. Minor criteria are

changes of discoid lupus erythematosus in the overlying

skin, lymphocytic vasculitis, mucin deposition, and

hyalinisation of subepidermal papillary zones. The

combination of four major and four minor criteria is

virtually diagnostic and permits differentiation from

other forms of panniculitis.[8]

In our two cases of confirmed lupus mastitis, one patient had extensive macrocalcifications in both breasts on

imaging, while the other had an infiltrative irregular

breast mass. Mammography, ultrasonography, and

MRI scans are used as imaging investigations for lupus

mastitis, as for other breast diseases. Various imaging

findings of lupus mastitis have been described,[4] [7] [9] [10] [11] [12] [13] [14]

depending on the stages of fat necrosis.

On mammography, large, dystrophic calcifications are

the most commonly encountered findings, as in one of

our cases.[7] Early mammographic findings include thin

curvilinear calcifications that, on subsequent images,

progressively enlarge and coarsen, mirroring the

pathologic evolution of focal panniculitis to maturing

subcutaneous fat necrosis.[9] Early calcifications frequently

simulate malignancy and present in a ductal distribution

or appear fine linear-branching in morphology. As

fat necrosis progresses, the calcifications increase in

size and become coarse and benign in appearance and

also can often be seen on ultrasound and MRI scans.[10]

Lupus mastitis can also present as a mass (often illdefined)

or asymmetry (focal or global) and may mimic

carcinoma.[7] Interval increase in mammographic density

and decreasing breast size over time can be present due

to underlying fibrosis.[11]

Sonographic findings of lupus mastitis also depend on

and reflect stages of fat necrosis. The most commonly

seen findings on ultrasonography are a hypoechoic ill-defined

mass, areas of architectural distortion, or changes

in echotexture of the breast that are more hyperechoic

due to infiltration of the subcutaneous fat and/or breast

parenchyma.[7] In patients who present with a discrete mass, non-specific features such as solid, irregular,

echogenic lesions with ill-defined margins have been

described.[5] [6] [13] Cutaneous involvement has also been

described and it is postulated to result from increased

vascularity in the subcutaneous plane, which may also

affect deeper planes than in the dermis.[4] [7] These findings

may mimic those of advanced breast carcinoma with

skin involvement. Calcifications with marked posterior

acoustic shadowing can be seen on ultrasonography when

dystrophic calcifications due to fat necrosis are present.

MRI is infrequently used for the evaluation of lupus

mastitis. The MRI features of lupus mastitis are

nonspecific and MRI can be helpful for showing

the extent of the disease and in demonstrating skin

involvement as in our case.[4] [7] [10] Some of the reported

MRI findings of lupus mastitis include skin thickening

with marked fat stranding, large coarse calcifications

seen as low-signal lesions, irregular masses (which

can demonstrate fat content) with rim enhancement

and a variable enhancement curve. The morphological

and kinetic features can be indistinguishable from

malignancy.[12] [13] [14] High signal intensity within the lesion

on pre-contrast scan with fat suppression may be hints

for underlying fat necrosis,[12] [13] [14] which was also seen in

our case of biopsy-proven lupus mastitis. A type 1 kinetic

curve was observed in our case, a finding that is usually

associated with benignity. As the enhancement pattern

for lupus mastitis can be variable, the morphology of

lesions on MRI scans is often more informative than

the kinetic curve alone. Overall MRI findings were

indistinguishable from malignancy, which emphasises

that MRI should not be performed to differentiate

between lupus mastitis and malignancy, but rather to

delineate the extent of known lupus mastitis.

The second case of lupus mastitis displayed

extensive coarse calcifications in both breasts on both

ultrasonography and mammography. Freehand FNA of

both breasts was performed by surgeons before imaging

with results showing no malignancy, thus further biopsy

was not performed after imaging after discussion with the

patient. Therefore, in cases of suspected lupus mastitis

where extensive calcifications are present, we suggest

core biopsy to allow histological analysis rather than

FNA. In addition, the history of SLE should be clearly

stated in the request form as this is important to allow

pathologists to accurately identify lupus mastitis.

Breast carcinoma, in particular inflammatory breast

carcinoma, can show clinical and radiological features similar to those of lupus mastitis, especially in patients

who present with a rapidly enlarging breast mass with

skin involvement.[7] Owing to the small number of cases

of lupus mastitis and breast malignancy in our cases,

we did not observe any specific imaging features to

distinguish between these two entities in our review.

The concept of lupus panniculitis being exacerbated by

localised trauma, such as biopsy, has been described.[8]

However, due to the similarities of clinical presentation

and imaging findings between lupus mastitis and breast

malignancy, we advocate biopsy for histopathological

correlation when suspicious imaging features are present.

The differential diagnosis of the findings seen in

lupus mastitis include diabetic mastopathy, idiopathic

granulomatous mastitis, and lymphoma. Clinical history

is crucial in distinguishing diabetic mastopathy from

lupus mastitis, while histopathological correlation

to rule out idiopathic granulomatous mastitis (which

lacks lymphocytic vasculitis), and immunohistological

chemical staining for lymphoma may be needed to

distinguish among these entities.

The clinical course of lupus mastitis is often chronic with

flares and remissions.[6] Both patients with lupus mastitis

had subjective breast mass during the follow-up periods

while they also had mild flares of other clinical aspects

of SLE. This suggests that the course of lupus mastitis

may be associated with the overall disease course and

process, though more research is needed to establish the

potential association.

Breast Mass

Apart from lupus mastitis, breast masses that affect

patients without lupus can also be present in patients with

SLE. Probably benign (BI-RADS 3) oval circumscribed

hypoechoic masses were the most frequently encountered

imaging findings in our patient cohort, as these are also

commonly seen in women without SLE. In our review,

all of the cases either showed benign pathological results

or were stable on imaging follow-up over the period of

3.5 to 7 years. These breast masses can be managed as

per those in patients who are unaffected by SLE.

Previous literature has shown that SLE is associated

with an increased risk of cancers overall, but is not more

significantly associated with breast cancer.[15] [16] Since the

radiological features of lupus mastitis, tumour and other

benign entities can overlap, as for patients unaffected

by SLE, histological correlation is warranted when

suspicious clinical and imaging features are present.

Calcifications

SLE causing lupus panniculitis is one of a few systemic

diseases that can cause stromal calcifications of the

breasts. Other systemic diseases which can cause diffuse

dystrophic calcifications of the subcutaneous fat include

scleroderma and dermatomyositis.[17] In lupus mastitis,

thin curvilinear calcifications seen in the early phase of

the disease progressively enlarge and coarsen to form

dystrophic calcifications due to the evolution of fat

necrosis as described earlier.

Other breast calcifications that are not lupus-related

can also be present in patients in SLE, for example a

suspicious group of fine pleomorphic microcalcifications

in the case of invasive ductal carcinoma. Biopsy is

warranted when suspicious microcalcifications are

present, as for patients without SLE.

Vascular Manifestations

Arterial calcifications observed as tram-track

calcifications on mammogram were present in three

of our patients (Figure 8). Patients with SLE have

been shown to have significantly higher prevalence

and extent of systemic arterial calcifications compared

with age- and sex-matched controls.[18] This is probably

multifactorial in nature, as lupus-related renal disease,

corticosteroid-induced dyslipoproteinaemia, and

secondary hypertension from renal disease all contribute

to accelerated atherosclerosis.[19] In our three cases with

arterial calcifications, two of them did not have history

of traditional risk factors for atherosclerosis, thus the arterial calcifications may be secondary consequence of

SLE, given their known history of lupus nephritis. On

mammography, arterial calcifications are regarded as

incidental findings with no specific treatment indicated.

Figure 8. Mammogram showing tram-track calcifications

compatible with arterial calcifications in a patient with systemic

lupus erythematosus.

Mondor’s disease is a rare entity characterised by

thrombophlebitis of superficial veins, usually of the

chest wall or breast.[20] Many possible aetiologies have

been described, including trauma, local inflammation,

malignancy, rheumatologic diseases including SLE, and

hypercoagulable states, which can be also associated

with SLE.[21] The presentation can be painful or painless,

classically with sudden appearance of a subcutaneous

cord. The course of the disease is benign and self-limiting,

lasting between 4 to 8 weeks.[22] Mammography

should be performed to exclude underlying malignancy,

which is one of the potential causes of Mondor’s

disease.[23] On mammography, the thrombosed, inflamed

vein is seen as a tubular density in the region of pain or

a palpable mass, which may be mistaken for a dilated

duct.[24] Ultrasound correlation is helpful, with findings

including an enlarged superficial vessel with absent

Doppler flow with or without intraluminal thrombus. A

thrombosed vein tends to be longer than a duct and has a

beaded appearance.[24]

Breast Oedema

On imaging, breast oedema is seen as breast enlargement,

increased parenchymal density, trabecular thickening,

increased interstitial markings, and skin thickening.[23] [25]

In patients with SLE, breast oedema can be secondary

to lupus-related chronic renal failure or congestive heart

failure, which usually affects both breasts but can be

unilateral with lateralisation to the dependent breast in

cases where patient is immobile. In patients with an upper

limb arteriovenous fistula for dialysis, unilateral breast

oedema can also occur secondary to complications of

arteriovenous fistula such as thrombosis.[9] Occasionally,

breast oedema can be associated with lupus mastitis, as in

the case in our patient cohort (Figure 3). As with patients

without SLE, breast oedema can also be caused by

venous obstruction, inflammatory breast cancer, mastitis,

post-irradiation changes, or lymphatic obstruction.

Axillary Lymphadenopathy

Many autoimmune diseases are associated with

lymphadenopathy, including rheumatoid arthritis,

Sjögren’s syndrome and SLE. Lymphadenopathy has

been reported to affect 23% to 34% of patients with

SLE. Seven of our 16 patients (43.8%) were reported

to have enlarged axillary lymph nodes, slightly higher than the reported percentage. In general, lymph nodes

related to SLE are soft, non-tender and vary in size and

there may be fluctuation of lymphadenopathy with SLE

disease exacerbations. Lymph node pathology in this

case generally showed diffuse hyperplasia with scarce

follicles.[26] [27]

In patients with SLE, axillary lymphadenopathy can

be due to the disease itself or occasionally related to

lupus mastitis. SLE has been shown to be associated

with an increased risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma

and Hodgkin lymphoma, which can also present

with lymphadenopathy.[15] Other causes of axillary

lymphadenopathy not related to SLE include metastasis

(most commonly from breast cancer), infection,

inflammatory causes, or granulomatous diseases.

On breast imaging, axillary lymph nodes are most

commonly seen on the mediolateral oblique view

mammogram or ultrasound. There can be considerable

overlap in morphological appearances of benign and

pathological lymph nodes on imaging. Features that

are suspicious for pathological lymph nodes include

loss of the normal fatty hilum, loss of the normal oval

or reniform shape, poorly circumscribed margins, and

increased size and opacity compared with findings on

prior images.[9] It is important to not assume that nodal

enlargement is reactive until malignancy has been ruled

out, and pathological correlation is warranted if clinical

suspicion is present.

In conclusion, our review showed a wide spectrum of

breast manifestations and mostly nonspecific imaging

findings that are primary or secondary to SLE. It is

important for clinicians and radiologists to be aware

of these SLE-related breast manifestations as they may

have an impact on the management plan. No recognised

imaging features distinguishing between lupus mastitis

and breast malignancy have been identified, and

pathological correlation is advocated in cases where

suspicious imaging features are demonstrated.

REFERENCES

1. Mok CC, Lau CS. Pathogenesis of systemic lupus erythematosus. J Clin Pathol. 2003;56:481-90. Crossref

2. Murphy G, Isenberg D. Effect of gender on clinical presentation

in systemic lupus erythematosus. Rheumatology (Oxford).

2013;52:2108-15. Crossref

3. Macura KJ, Ouwerkerk R, Jacobs MA, Bluemke DA. Patterns of

enhancement on breast MR images: interpretation and imaging

pitfalls. Radiographics. 2006;26:1719-34. Crossref

4. Cho CC, Chu WC, Tang AP. Lupus Panniculitis of the breast—mammographic and sonographic features of a rare manifestation of systemic lupus. Hong Kong J Radiol. 2008;11:41-3.

5. Rosa M, Mohammadi A. Lupus mastitis: a review. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2013;17:230-3. Crossref

6. Georgian-Smith D, Lawton TJ, Moe RE, Couser WG. Lupus mastitis: radiologic and pathologic features. AJR Am J Roentgenol.

2002;178:1233-5. Crossref

7. Voizard B, Lalonde L, Sanchez LM, Richard-Chesnay J, David J, Labelle M, et al. Lupus mastitis as a first manifestation of systemic disease: about two cases with a review of the literature. Eur J Radiol. 2017;92:124-31. Crossref

8. De Bandt M, Meyer O, Grossin M, Kahn MF. Lupus mastitis

heralding systemic lupus erythematosus with antiphospholipid

syndrome. J Rheumatol. 1993;20:1217-20.

9. Cao MM, Hoyt AC, Bassett LW. Mammographic signs of systemic

disease. Radiographics. 2011;31:1085-100. Crossref

10. Mosier AD, Boldt B, Keylock J, Smith DV, Graham J. Serial MR

findings and comprehensive review of bilateral lupus mastitis with

an additional case report. J Radiol Case Rep. 2013;7:48-58. Crossref

11. Lee SJ, Saidian L, Wahab RA, Khan S, Mahoney MC. The evolving

imaging features of lupus mastitis. Breast J. 2019;25:753-4. Crossref

12. Thapa A, Parakh A, Arora J, Goel RK. Lupus mastitis of the male

breast. BJR Case Rep. 2015;2:20150290. Crossref

13. Sabaté JM, Gómez A, Torrubia S, Salinas T, Clotet M, Lerma E.

Lupus panniculitis involving the breast. Eur Radiol. 2006;16:53-6. Crossref

14. Pinho MC, Souza F, Endo E, Chala LF, Carvalho FM, de Barros N.

Nonnecrotizing systemic granulomatous panniculitis involving the

breast: imaging correlation of a breast cancer mimicker. AJR Am

J Roentgenol. 2007;188:1573-6. Crossref

15. Song L, Wang Y, Zhang J, Song N, Xu X, Lu Y. The risks of

cancer development in systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE)

patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arthritis Res Ther.

2018;20:270. Crossref

16. Rezaieyazdi Z, Tabaei S, Ravanshad Y, Akhtari J, Mehrad-Majd H.

No association between the risk of breast cancer and systemic lupus

erythematosus: evidence from a meta-analysis. Clin Rheumatol.

2018;37:1511-9. Crossref

17. Łukasiewicz E, Ziemiecka A, Jakubowski W, Vojinovic J,

Bogucevska M, Dobruch-Sobczak K. Fine-needle versus core-needle

biopsy—which one to choose in preoperative assessment

of focal lesions in the breasts? Literature review. J Ultrason.

2017;17:267-74. Crossref

18. Yiu KH, Wang S, Mok MY, Ooi GC, Khong PL, Mak KF, et al.

Pattern of arterial calcification in patients with systemic lupus

erythematosus. J Rheumatol. 2009;36:2212-7. Crossref

19. Lalani TA, Kanne JP, Hatfield GA, Chen P. Imaging findings in

systemic lupus erythematosus. Radiographics. 2004;24:1069-86. Crossref

20. Amano M, Shimizu T. Mondor’s disease: a review of the literature. Intern Med. 2018;57:2607-12. Crossref

21. Raviv B, Israelit SH. Mondor’s disease of the chest wall—a forgotten

cause of chest pain: clinical approach and treatment. J Gen Pract.

2014;2:3. Available from: https://www.hilarispublisher.com/open-access/

mondors-disease-of-the-chest-wall-a-forgotten-cause-of-chest-pain-clinical-approach-and-treatment-2329-9126.1000157.pdf. Accessed 29 Oct 2019.

22. Crisan D, Badea R, Crisan M. Thrombophlebitis of the lateral

chest wall (Mondor’s disease). Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol.

2014;80:96. Crossref

23. Dilaveri C, Mac Bride MB, Sandhu NP, Neal L, Ghosh K,

Wahner-Roedler DL. Breast manifestations of systemic diseases.

Int J Womens Health. 2012;4:35-43. Crossref

24. Shetty MK, Watson AB. Mondor’s disease of the breast:

sonographic and mammographic findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2001;177:893-6. Crossref

25. Kwak JY, Kim EK, Chung SY, You JK, Oh KK, Lee YH, et al.

Unilateral breast edema: spectrum of etiologies and imaging

appearances. Yonsei Med J. 2005;46:1-7. Crossref

26. Shapira Y, Weinberger A, Wysenbeek AJ. Lymphadenopathy in systemic lupus erythematosus. Prevalence and relation to disease

manifestations. Clin Rheumatol. 1996;15:335-8. Crossref

27. Melikoglu MA, Melikoglu M. The clinical importance of lymphadenopathy in systemic lupus erythematosus. Acta Reumatol

Port. 2008;33:402-6. Crossref