Prophylactic Caesarean Iliac Artery Balloon Insertion in Patients with Abnormal Placental Implantation

ORIGINAL ARTICLE CME

Prophylactic Caesarean Iliac Artery Balloon Insertion in Patients with Abnormal Placental Implantation

CSC Tsai1, SSM Wong1, CMY Chung2, SCH Yu1

1 Department of Imaging and Interventional Radiology, Prince of Wales Hospital, Hong Kong

2 Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Prince of Wales Hospital, Hong Kong

Correspondence: Prof SCH Yu, Department of Imaging & Interventional Radiology, Prince of Wales Hospital, Hong Kong. Email: simonyu@cuhk.edu.hk

Submitted: 6 Aug 2019; Accepted: 10 Dec 2019.

Contributors: All authors designed the study. CSCT, SSMW and CMYC acquired the data. CSCT and SSMW analysed the data and drafted the

manuscript. All authors critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors had full access to the data, contributed to

the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Funding/Support: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data Availability: All data generated or analysed during the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: This study was approved by the Joint Chinese University of Hong Kong–New Territories East Cluster Clinical Research Ethics Committee (Ref 2019.577). The requirement for patient consent was waived for this retrospective study.

Abstract

Introduction

We evaluated the safety and obstetric outcomes of patients with abnormal placental implantation who underwent prophylactic Caesarean iliac balloon insertion.

Methods

Clinical and procedural records of patients with abnormal placental implantation (i.e., high-grade

placenta praevia and/or placenta accreta) undergoing prophylactic Caesarean iliac artery balloon insertion in a

tertiary referral hospital from September 2009 to April 2016 were reviewed. Patients’ demographics, procedural

complications (e.g., dissection and thromboembolism) and outcomes (estimated blood loss, transfusion requirements,

immediate/delayed hysterectomy rate, postoperative sepsis, and immediate maternal/fetal mortality) were analysed.

Results

Twenty-three cases were included in the study. The median age of the patients was 36 years (range,

28-47 years). A total of 91.3% (21/23) were high-grade placenta praevia (34.8% grade III and 56.5% grade IV)

with 69.6% (16/23) co-existing placenta accreta. All prophylactic iliac balloon insertion procedures were uneventful

without major complications such as dissection or thromboembolic events. The median blood loss was 1700 mL

(100-8000 mL). The mean units of packed cells, platelets, and fresh frozen plasma transfused were 2.5, 2.2, and

2.0, respectively. The immediate and delayed hysterectomy rates were 34.8% (8/23) and 13.0% (3/23), respectively.

Postoperative sepsis incidence was 8.7% (2/23). No immediate maternal or fetal mortality was recorded. Overall,

the obstetric outcomes were comparable to data published in the literature.

Conclusion

Prophylactic Caesarean iliac artery balloon insertion for patients with abnormal placental implantation

is feasible and safe. The obstetric outcomes were comparable to data published in the literature.

Key Words: Balloon occlusion; Iliac artery; Placenta accreta; Placenta previa; Radiology, interventional

中文摘要

異常胎盤植入患者預防性剖宮產髂動脈球囊置入術

蔡紹俊、王先民、鍾汶欣、余俊豪

引言

評估接受預防性剖宮產髂骨球囊置入術的異常胎盤植入患者的安全性和產科結果。

方法

回顧2009 年 9 月至 2016 年 4 月期間在三級轉介醫院接受預防性剖宮產髂動脈球囊置入術的異常胎盤植入患者(即第三級或第四級前置胎盤以及/或者植入性胎盤)的臨床和手術記錄。分析患者的基本資料訊息、手術併發症(如撕裂和血栓栓塞)和結果(估計失血量、輸血需求、即時/延遲子宮切除率、術後敗血症和產婦/胎兒即時死亡率)。

結果

共納入23例。患者年齡中位數為36歲(介乎28-47歲)。23名患者中,21名(91.3%)出現嚴重前置胎盤(第三級佔34.8%,第四級佔56.5%),16名(69.6%)併有胎盤植入。所有預防性髂骨球囊置入術均成功,沒有出現撕裂或血栓栓塞事件等重大併發症。失血量中位數為1700 毫升(介乎100-8000毫升)。 紅血球濃厚液、血小板和新鮮冷凍血漿的平均用量分別為2.5、2.2和2.0。即時和延遲子宮切除率分別為34.8%(8例)和13.0%(3例)。術後敗血症發生率為 8.7%(2例)。沒有錄得產婦/胎兒即時死亡。總體而言,產科結果與文獻數據相若。

結論

胎盤植入異常患者進行預防性剖宮產髂動脈球囊置入術是可行且安全的。 產科結果與文獻數據相若。

INTRODUCTION

Abnormal placental implantation represents a major

challenge to obstetricians in terms of its high risks

of massive haemorrhage, disseminated intravascular

coagulopathy, sepsis, and the resulting maternal and/or

fetal mortality. Risk factors for placenta accreta include

placenta praevia, previous Caesarean section, uterine

surgery, multiparity, and advanced maternal age.[1] With

a rising incidence of abnormal placental implantation

in recent years due to increasing surgical delivery rates

worldwide,[2] multidisciplinary input from obstetricians,

obstetric anaesthetists, and interventional radiologists

are recognised as pivotal to improve obstetric outcomes.

An interventional radiology approach for management

of patients with placenta accreta and its variants was

first described by Dubois et al in 1997.[3] It involved

prophylactic balloon occlusion of the anterior division

of the internal iliac arteries followed by uterine artery

embolisation. Since then, investigations have been carried

out by various groups looking into its clinical efficacy. In

a retrospective study by Tan et al,[4] preoperative internal

iliac artery balloon occlusion reduced intraoperative

blood loss and transfusion requirements in patients with

placenta accreta and its variants undergoing Caesarean

delivery. Other studies by Shrivastava et al[5], Bodner et al,[6] and Salim et al[7] failed to show benefit of prophylactic

balloon occlusion in terms of blood loss reduction

or transfusion requirements. Therefore, its role in

management of abnormal placental implantation remains

controversial. Our study aimed to further evaluate the

safety and obstetric outcomes of patients who received

prophylactic Caesarean iliac artery balloon insertion.

METHODS

Study Design and Patients

This was a retrospective case series study, reported in

accordance with the Strengthening the Reporting of

Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE)

guidelines.[8] The clinical records and procedural details of

23 consecutive patients with a high suspicion of abnormal

placental implantation, based on clinical risk factors

and ultrasonographic and magnetic resonance imaging

findings, that underwent prophylactic Caesarean iliac

artery balloon insertion in the period from September

2009 to April 2016 were retrospectively reviewed.

Procedure

The internal iliac balloon insertions were performed

on an elective basis in the angiography suite of the

radiology department. Balloon insertion procedures were

performed by a senior interventional radiologist with 18 years of experience (SCHY). Bilateral femoral

punctures were performed and 7-Fr femoral sheaths

(Radifocus; Terumo Corporation, Tokyo, Japan)

introduced. Both internal iliac arteries were sequentially

cannulated with 5-Fr catheters (RIM; Cook Medical,

Bloomington [IN], US) over a guidewire (Terumo)

using the contralateral approach (i.e., cannulation of the

left internal iliac artery via right femoral access and vice

versa). A 6-Fr compliance balloon catheter (Berenstein

Occlusion Balloon, Boston Scientific, Natick [MA], US)

was placed in the main trunk or anterior division of each

internal iliac artery (Figure 1). The balloon catheters

were connected to a container with 0.4 to 0.7 mL contrast

(Omnipaque, GE Healthcare). The catheters were then

carefully anchored to the inguinal region with sutures and

semipermeable polyurethane membranes (Tegaderm,

3M Healthcare, St. Paul [MN], US) and taped to the lower

limbs (Figure 2). In order to reduce procedural radiation

dose, a low pulse rate (≤6.25 frames/s), coning/shielding,

and avoidance of digital subtraction angiography (with

roadmap only) were adopted.

Figure 1. Digital subtraction angiographic image showing balloon in situ within the internal iliac artery.

Figure 2. Balloon catheters carefully affixed to the inguinal regions

and lower limbs with sutures and semipermeable polyurethane

membranes.

Patients were then transferred to the obstetric theatre for

Caesarean delivery. Inflation of the balloon catheters was performed by the attending obstetricians after

the fetus was fully delivered and the umbilical cord

clamped. The need for balloon inflation would be

assessed by the obstetrician depending on the degree

of postpartum haemorrhage, which also determined

subsequent management with options including primary

hysterectomy, a conservative approach with uterus

and placenta in situ or uterine artery embolisation

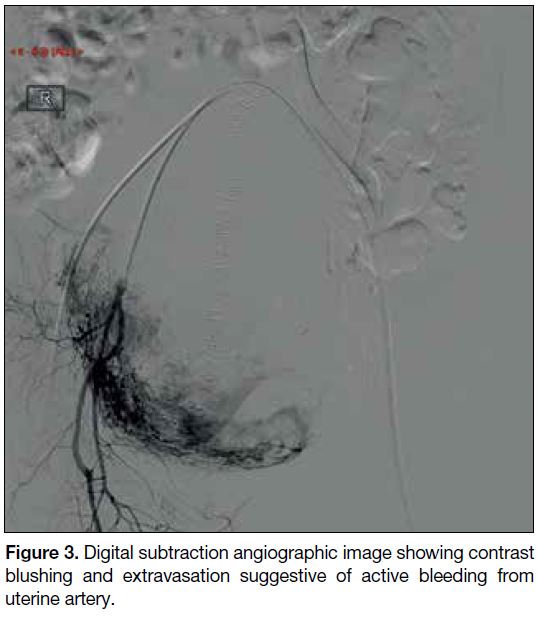

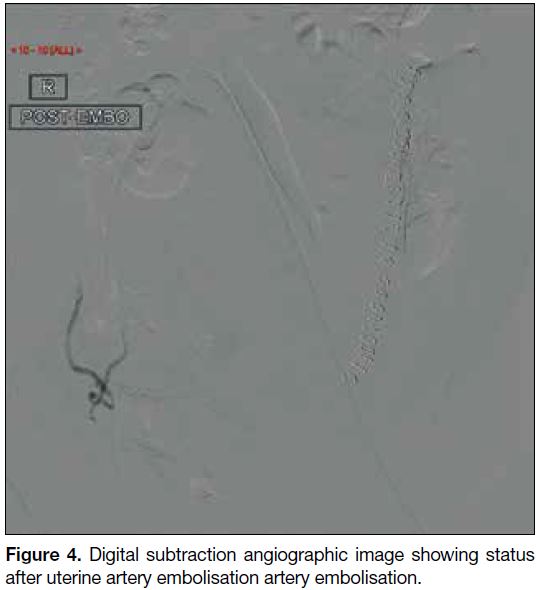

(Figures 3 and 4) using an absorbable gelatine sponge

slurry (Gelfoam; Upjohn, Kalamazoo [MI], US). The

obstetricians had the option of checking the balloon

catheters’ position intraoperatively using a C-arm if

necessary. Intravenous antibiotics were not routinely

administered unless there were signs of endometritis.

Figure 3. Digital subtraction angiographic image showing contrast

blushing and extravasation suggestive of active bleeding from

uterine artery.

Figure 4. Digital subtraction angiographic image showing status

after uterine artery embolisation artery embolisation.

The diagnosis of placenta accreta was confirmed either

intraoperatively when the placenta failed to be detached

with gentle controlled cord traction or pathologically

when the uterus and placenta were removed. For patients

with the placenta left in situ, serial ultrasound was

performed to monitor involution of the placenta in the

postoperative period.

Statistical Analysis

Basic patient demographics including the patients’ age,

gestational age, gravidity and parity, history of Caesarean

section, and other uterine surgery were recorded.

Obstetric outcomes, including estimated blood loss

during Caesarean section (as documented in the surgical record), requirements for blood product transfusion

(packed red blood cells [PRBCs], platelets, and fresh

frozen plasma [FFP]), hysterectomy rate (including

whether it was immediate or delayed), and complications

related to hysterectomy and balloon insertion were also

recorded.

Parametric variables are presented as mean and standard

deviation while non-parametric variables are presented

as median and range. Categorical variables are presented

as percentages. Statistical analysis was performed using

commercial software (SPSS Windows version 19.0;

IBM Corp, Armonk [NY], US).

RESULTS

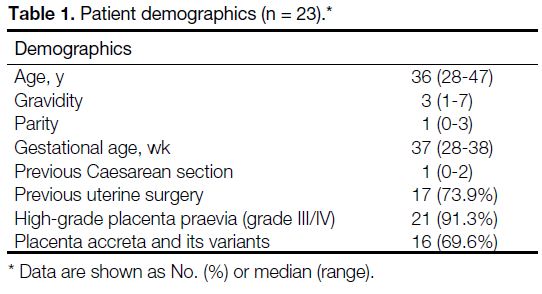

Patient Cohort

From September 2009 to April 2016, 24 prophylactic

iliac artery balloon insertions were performed. One case

performed for uterine arteriovenous malformations was

excluded, leaving a total of 23 cases for analysis. The

basic demographics of our patients are described in

Table 1. This group of patients demonstrated known

risk factors for abnormal placental implantation, such as

relatively advanced maternal age (median age=36 years)

and a history of Caesarean section or uterine surgery/curettage (74% of current patient cohort). Median

gravidity was 3 (range, 1-7) and parity was 1 (range,

0-3).

Table 1. Patient demographics (n = 23).

In these 23 cases, 69.6% (16/23) had the diagnosis

of placenta accreta or its variants confirmed either

intraoperatively or pathologically. A high percentage of

the cases had co-existing high-grade placenta praevia of

grade III (34.8%; 8/23) or IV (56.5%; 13/23) [Table 1].

Among the 23 cases, bleeding in two cases was deemed

not excessive and thus the obstetricians decided inflation

of the balloon catheters was not necessary. One of these

two cases had no accreta, as cord traction resulted in

complete separation of the placenta from the uterine wall

and the placenta was found to be complete. Inflation

of the balloons was not clearly documented in another

case, for a total percentage of confirmed actual balloon

inflation of 87% (20/23).

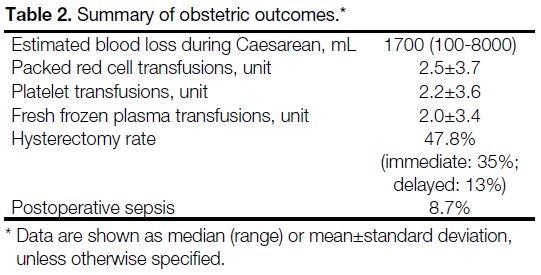

Obstetric Outcome

The estimated median blood loss during Caesarean

section was 1700 mL (range, 100-8000 mL). Blood

product transfusions thus were required by most patients,

with a mean of 2.5 (±3.7) units of PRBCs, 2.2 (±3.6) units

of platelet, and 2.0 (±3.4) units of FFP.

Immediate hysterectomy, primarily in order to control

blood loss, was performed in eight cases (35%)

while delayed hysterectomy was performed in three

cases, due to endometritis, placental infection, and

haemoperitoneum post-Caesarean section. Four cases

had retained placenta due to morbid adhesion and did not

require hysterectomy. Two of the four cases subsequently

developed infection of the retained placenta and one

required a delayed hysterectomy. No major structural

complications were reported. One case of loss of bladder

sensation was documented. There were no reported

injuries to the ureters or bowel during hysterectomy

or Caesarean section. Immediate postoperative uterine

artery embolisation was carried out in five patients

(21.7%; 5/23). Only one patient required repeated

uterine artery embolisation, which was performed to

control bleeding from a retained placenta 2 months after

the delivery. Postoperative sepsis was documented in

8.7% (2/23) of patients (Table 2).

Table 2. Summary of obstetric outcomes.

Technical Outcome

All the iliac balloon insertions were technically

successful. No balloon-related complications such as

vascular dissection or thromboembolism were reported

in these 23 cases. There was one case of balloon self-deflation

where reinflation was needed due to a loosened

3-way stopcock.

The mean radiation dose to the mother incurred in

the prophylactic Caesarean catheter insertion was

177 000±244 251 mGycm2, while mean fluoroscopic

screening time was 373±228 s. Estimated effective

dose was 46 mSv (conversion factor 0.26, adopted

from The National Council on Radiation Protection and

Measurements 2009).[9] Mean fetal dose was 11.2 mGy.

DISCUSSION

The basic demographics of our current cohort of

patients with relatively advanced maternal age, and

a high prevalence of previous Caesarean section/uterine surgery, show similarity to data published in the

literature.[4] [5] [6] The high percentage of intraoperatively/pathologically diagnosed placenta accreta or its variants

and co-existing high praevia are consistent with the

findings of Shrivastava et al[5] and Salim et al.[7]

In the assessed obstetric outcomes, the estimated amount

of blood loss was comparable to published data on

patients undergoing balloon occlusion. The requirement

for blood product transfusion (PRBCs, platelets, and

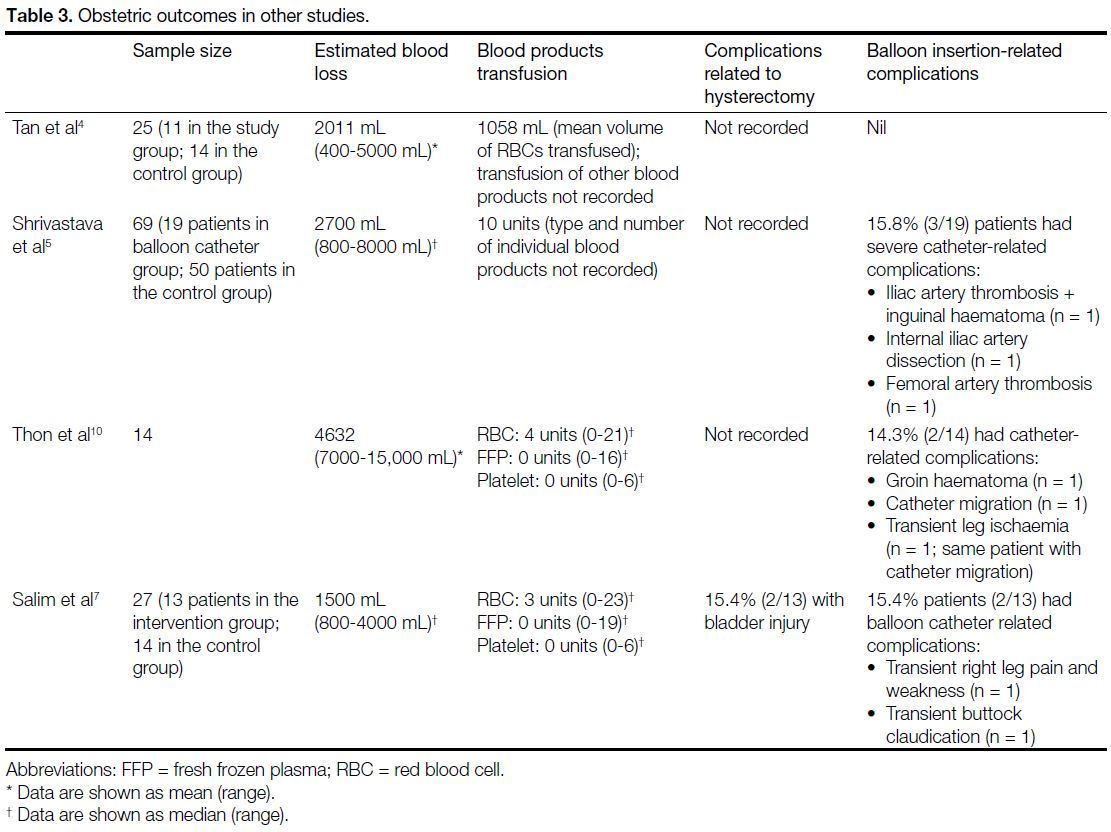

FFP) varies significantly in the literature (Table 3[4] [5] [7] [10]),

with total units of blood product transfusion up to 10 in

a balloon catheter intervention group.[5] In contrast to this,

estimated blood loss and the need for blood products

was comparable/comparatively moderate in this cohort

of patients.

Table 3. Obstetric outcomes in other studies.

Conflicting evidence is observed in the literature

regarding the efficacy of the placement of internal iliac

artery balloons. In 2012, Dilauro et al[11] analysed 20 case

reports, including three case-control studies, seven

multiple-case series, and 10 single-case reports involving

a total of 132 patients who underwent this procedure,

and found that the reduction in postpartum haemorrhage

or transfusion requirements were inconsistent among

different investigators. Tan et al[4] reported a significant

decrease in intraoperative blood loss in patients with

occlusion balloon versus Caesarean section alone

(2011 mL vs. 3316 mL; p = 0.042) and reduction

in required blood transfusion volume (1058 mL vs.

2211 mL; p = 0.005). Angstmann et al[12] demonstrated

a significant decrease in intraoperative blood loss

(553 mL vs. 4517 mL; p < 0.001) and the need for

transfusion (p = 0.001). However, other studies such as

Levine et al,[13] Shrivastava et al,[5] and Salim et al[7] showed

no significant differences in estimated intraoperative

blood loss, need for transfused blood products, or length

of hospital stay. The available literature is mostly small-scale

retrospective studies and very few randomised controlled studies.[7] We believe that non-standardisation

of procedure techniques, operator experience, and

factors such as patient referral pattern and selection bias

are causing such inconclusive evidence and thus the

ambiguity about its efficacy. Also, there are potential

ethical limitations in performing randomised controlled

studies in this group of patients with high obstetric risks

leading to only very few randomised prospective studies

in this topic.

Reasons for failure to reduce intraoperative risks of

bleeding or obstetric outcomes may be due to the

presence of extensive vascular anastomoses in the gravid

uterus. The collateral arterial supply from the cervical,

ovarian, rectal, and even lumbar arteries can contribute

to overall blood loss[19] even the uterine arteries have been

occluded by balloon catheters. Kidney et al[14] have argued

that the presence of distended balloons reduces arterial

pressure to that of venous pressure, and by this means,

haemostasis and blood clot formation can be facilitated.

Therefore, investigators have also been trying to modify

the balloon occlusion technique by placing the balloon

at more proximal sites, such as at the common iliac

arteries or the infrarenal abdominal aorta. This was

performed with an aim to arrest the extensive collateral

flow arising proximal to the internal iliac arteries.

Omar et al[15] reviewed 19 studies, including 57 cases

of prophylactic arterial balloon occlusion performed at

multiple sites, including the abdominal aorta, common

iliac arteries, internal iliac arteries, the anterior division

of the internal iliac arteries and the uterine arteries. The

authors observed there is more conflicting evidence when

balloons were placed in the internal iliac arteries or the

uterine arteries, with one positive controlled study4 and

three negative controlled studies.[5] [6] [13] Angstmann et al[12]

placed balloon occlusion catheters in the common

iliac arteries and yielded positive result with reduction

in maternal morbidity. Authors of three case reports

using balloon occlusion in the abdominal aorta reported

favourable outcome as well.[16] [17] [18] A more recent study performing temporary occlusion of the infrarenal aorta

in 42 cases also gave favourable outcomes (estimated

blood loss 0.58 L).[19] Omar et al[15] postulated the clinical

success could be proportional to the ability of abolishing

the extensive collateral blood supply. To support or

validate this deduction, large-scale randomised and

prospective studies will be required. The safety profile of

more proximal balloon occlusion, such as in the common

iliac arteries or abdominal aorta, will have to be carefully

evaluated because potential complications include lower

limb ischaemia, lower limb embolism, reperfusion

injury, vessel thrombosis, and aortic rupture. Also,

aortic balloons have a much larger profile and are thus

more prone to migration during inflation. Its inflation

process will also likely increase the blood pressure due

to significant obstruction to circulation.

In our review of the procedural records of these 23

prophylactic internal iliac balloon catheter insertions,

it showed that this procedure could be performed

safely and was feasible. No major significant balloon

insertion–related complications were found in this

cohort of patients. However, arterial thrombosis, a major

complication requiring thrombectomy,[20] [21] and minor

complications such as transient leg pain, weakness,

and claudication have been reported.[7] [10] This aspect is

particularly important as major vascular complications

could have significant implications in these patients.

A well-defined safety profile will be essential in

establishing the efficacy of this prophylactic procedure,

assuming it is proven in randomised controlled trials to

be of benefit.

There were no hysterectomy-related complications in

terms of structural damage to the adjacent organs such

as the bowel, ureters or urinary bladder. One case of loss

of urinary bladder sensation was documented, however,

which may have been caused by inadvertent damage to

adjacent pelvic nerves.

It is always important to minimise radiation exposure

to both mothers and especially fetuses, so meticulous

techniques were employed, including low pulse rate

(≤6.25 frame/s), coning/shielding, and avoidance of

digital subtraction angiography (with roadmap only).

The mean fetal dose observed in the present study was

11.2 mGy. This represents a probability of birth without

malformation or childhood cancer of approximately

95.8% compared with 95.9% in children without

radiation exposure. This probability is 0.1% higher

than that in children born without radiation exposure during pregnancy.[22] This needs to be balanced against

the potential benefits of reduction of intraoperative blood

loss and need for transfusion,[4] [12] again necessitating a

randomised controlled multicentre trial.

The strength of current study was the consistency

of the balloon catheter procedures, as it was carried

out/supervised by single experienced interventional

radiologist, and the relatively large number of patients.

However, it is limited by its lack of a control group for

direct comparison and the fact that not all patients were

confirmed to have placenta accreta. Future studies with

standardised procedure protocol in prospective setting

will be helpful to evaluate and establish the clinical

efficacy of prophylactic internal iliac balloon insertion.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated prophylactic

internal iliac balloon insertion for patients with suspected

abnormal placental implantation is safe and feasible. The

obstetric outcomes were comparable to data in the major

literature.

REFERENCES

1. Miller DA, Chollet JA, Goodwin TM. Clinical risk factors for placenta previa-placenta accreta. Am J Obstet Gynecol.

1997;177:210-4. Crossref

2. Matthews TG, Crowley P, Chong A, McKenna P, McGarvey C, O’Regan M. Rising caesarean section rates: a cause for concern?

BJOG. 2003;110:346-9. Crossref

3. Dubois J, Garel L, Grignon A, Lemay M, Leduc L. Placenta percreta: balloon occlusion and embolization of the internal iliac

arteries to reduce intraoperative blood losses. Am J Obstet Gynecol.

1997;176:723-6. Crossref

4. Tan CH, Tay KH, Sheah K, Kwek K, Wong K, Tan HK, et al. Perioperative endovascular internal iliac artery occlusion balloon

placement in management of placenta accreta. AJR Am J

Roentgenol. 2007;189:1158-63. Crossref

5. Shrivastava V, Nageotte M, Major C, Haydon M, Wing D. Case-control comparison of cesarean hysterectomy with and without

prophylactic placement of intravascular balloon catheters for

placenta accreta. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;197:402.e1-5. Crossref

6. Bodner LJ, Nosher JL, Gribbin C, Siegel RL, Beale S, Scorza W.

Balloon-assisted occlusion of the internal iliac arteries in patients

with placenta accreta/percreta. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol.

2006;29:354-61. Crossref

7. Salim R, Chulski A, Romano S, Garmi G, Rudin M, Shalev E.

Precesarean prophylactic balloon catheters for suspected

placenta accreta: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol.

2015;126:1022-8. Crossref

8. von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC,

Vandenbroucke JP, et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of

Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement:

guidelines for reporting observational studies. Epidemiology.

2007;18:800-4. Crossref

9. National Council on Radiation Protection and Measurements.

Report 160 — Ionizing Radiation Exposure of the Population of the

United States. Available from: https://ncrponline.org/publications/reports/ncrp-report-160-2/. Accessed 11 Jun 2019.

10. Thon S, McLintic A, Wagner Y. Prophylactic endovascular

placement of internal iliac occlusion balloon catheters in parturients

with placenta accreta: a retrospective case series. Int J Obstet

Anesth. 2011;20:64-70. Crossref

11. Dilauro MD, Dason S, Athreya S. Prophylactic balloon occlusion

of internal iliac arteries in women with placenta accreta: literature

review and analysis. Clin Radiol. 2012;67:515-20. Crossref

12. Angstmann T, Gard G, Harrington T, Ward E, Thomson A,

Giles W. Surgical management of placenta accreta: a cohort series

and suggested approach. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;202:38.e1-9. Crossref

13. Levine AB, Kuhlman K, Bonn J. Placenta accreta: comparison of

cases managed with and without pelvic artery balloon catheters. J

Matern Fetal Med. 1999;8:173-6. Crossref

14. Kidney DD, Nguyen AM, Ahdoot D, Bickmore D, Deutsch LS,

Majors C. Prophylactic perioperative hypogastric artery balloon

occlusion in abnormal placentation. AJR Am J Roentgenol.

2001;176:1521-4. Crossref

15. Omar HR, Karlnoski R, Mangar D, Mangar D, Patel R, Hoffman M,

Camporesi E. Staged endovascular balloon occlusion versus

conventional approach for patients with abnormal placentation: a

literature review. J Gynecol Surg. 2012;28:247-54. Crossref

16. Paull JD, Smith J, William L, Davison G, Devine T, Holt M. Balloon

occlusion of the abdominal aorta during caesarean hysterectomy for placenta percreta. Anaesth Intensive Care. 1995;23:731-4. Crossref

17. Bell-Thomas SM, Penketh RJ, Lord RH, Davies NJ, Collis R.

Emergency use of a transfemoral aortic occlusion catheter to

control massive haemorrhage at caesarean hysterectomy. BJOG.

2003;110:1120-2. Crossref

18. Masamoto H, Uehara H, Gibo M, Okubo E, Sakumoto K, Aoki Y.

Elective use of aortic balloon occlusion in caesarean hysterectomy

for placenta previa percreta. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2009;67:92-5. Crossref

19. Duan XH, Wang YL, Han HW, Chen ZM, Chu QI, Wang L, et al.

Caesarean section combined with temporary aortic balloon

occlusion followed by uterine artery embolisation for the

management of placenta accreta. Clin Radiol. 2015;70:932-7. Crossref

20. Sewell MF, Rosenblum D, Ehrenberg H. Arterial embolus during common iliac balloon catheterization at cesarean hysterectomy. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108:746-8. Crossref

21. Royal College of Obstetricians & Gynaecologists. Placenta

praevia, placenta praevia accreta and vasa praevia: diagnosis

and management (Green-top Guideline No. 27). 2011. Available

from: https://www.rcog.org.uk/en/guidelines-research-services/

guidelines/gtg27/. Accessed 17 Jun 2019.

22. McCollough CH, Schueler BA, Atwell TD, Braun NN, Regner DM, Brown DL, et al. Radiation exposure and pregnancy: when should

we be concerned? Radiographics. 2007;27:909-17. Crossref