Setting Standards for Judging the Rapid Film Reporting Section in Postgraduate Radiology Assessment: a Feasibility Study

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Setting Standards for Judging the Rapid Film Reporting Section in Postgraduate Radiology Assessment: a Feasibility Study

AF Abdul Rahim1, NS Roslan1, IL Shuaib2, MS Abdullah3, KA Sayuti3, H Abu Hassan4

1 Department of Medical Education, School of Medical Sciences, Universiti Sains Malaysia, Malaysia

2 Department of Radiology, Advanced Medical and Dental Institute, Universiti Sains Malaysia, Malaysia

3 Department of Radiology, School of Medical Sciences, Universiti Sains Malaysia, Malaysia

4 Department of Radiology, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Universiti Putra Malaysia, Malaysia

Correspondence: Dr AF Abdul Rahim, Department of Medical Education, School of Medical Sciences, Universiti Sains Malaysia,

Malaysia. Email: fuad@usm.my

Submitted: 8 Mar 2020; Accepted: 4 Jun 2020.

Contributors: AFAR and NSR designed the study. ILS, MSA, KAS, and HAH acquired the data. AFAR, NSR analysed the data. AFAR, NSR,

ILS, and HAH drafted the manuscript. All authors critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors had full access

to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Funding/Support: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics Approval: The study was granted an exemption from ethical approval from the Human Research Ethics Committee USM. The participants

were treated in accordance with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. The participants provided written informed consent for all data

collection.

Abstract

Objective

We investigated the feasibility of applying a standard-setting procedure for the rapid film reporting

examination of the Malaysian National Conjoint Board of Radiology.

Methods

We selected the modified Angoff standard-setting process. Judges were nominated and trained, performance

categories were discussed, and judges’ ratings on films were collected after an iterative procedure. The process was

then evaluated for evidence of validity.

Results

A cut-off score of 92% resulted, compared with the 80% usually used. Judges were satisfied with the training

and understood the procedure and their roles. In all, 27.3% felt that time given for the task was not sufficient. A

total of 54.5% of judges thought the final passing cut-off score of 92% was too high, and 27.3% were not confident

regarding its appropriateness. The inter-rater reliability was 0.928. External comparison with a ‘gold standard’ of

supervisor ratings revealed a sensitivity of 0.25 and specificity of 1.00 compared with the traditional cut-off score

having a sensitivity of 0.92 and specificity of 0.33. In this kind of situation, high specificity is considered to be more

important than high sensitivity.

Conclusion

Standard setting for the rapid film reporting examination using the modified Angoff method was feasible

with robust procedural, internal, and external validity evidence. Areas for improvement were identified to address

the perceived high cut-off score obtained and improve the overall process.

Key Words: Education, medical; Preceptorship; Psychometrics; Radiology; Teacher training

中文摘要

於放射科培訓醫生的快速放射影像報告考核中使用標準設定:可行性研究

AF Abdul Rahim、NS Roslan、IL Shuaib、MS Abdullah、KA Sayuti、H Abu Hassan

目的

檢視馬來西亞國家放射學聯合委員會以設定快速放射影像報告考核標準的可行性。

方法

採用改良版Angoff標準設定法,獲提名考官須經過培訓、討論考核表現類別,並以迭代程序收集考官對放射影像片子的評級,然後對該程序進行有效性評估。

結果

跟一般使用的劃割分數80%相比,本研究的劃割分數為92%。考官對培訓感到滿意,並且

理解過程和他們的角色。當中,27.3%認為完成任務時間不足,54.5%認為最終合格分數過高(即

92%),27.3%對這個合格分數的適當性存疑。評分者間一致度信度為0.928。與主管級醫師評級的

「黃金標準」進行外部比較時,使用劃割分數92%的靈敏度為0.25,特異性為1.00;使用傳統劃割分

數(即80%)的靈敏度則為0.92,特異性為0.33。在這種情況下,高特異性比高靈敏度更為重要。

結論

基於過程上、內部和外部的可靠效度,快速放射影像報告考核中使用改良版Angoff標準設定

法是可行的。研究也就劃割分數過高提出改進之處,以改善整個程序。

INTRODUCTION

Assessment in medical education is an important

undertaking; one of its goals is protecting the public by

upholding high professional standards.[1] Over the past

two decades, medical schools and postgraduate training

bodies have put in rigorous efforts to provide valid

assessment in certifying physicians. This is guided by

the current view of validity as a hypothesis that must be

supported by evidence.[2]

The Malaysian National Conjoint Board of Radiology,

responsible for the training of radiologists in Malaysia,

has recently embarked on gradually improving the

assessment of its graduates. The establishment of

standard setting of the assessment procedure is a priority

area.

The 4-year training programme is currently divided into

three phases. Phase I is the first year, phase II covers

the second and third years, and the fourth year is phase

III. Assessment is divided into continuous and end-of-phase professional examinations. Examinations in

Phase I include a multiple true-false (Type X) question

examination, an objective structured clinical examination,

an objective structured practical examination, and an oral

examination. In Phase II the professional examinations

include multiple-choice tests, film reporting, and an oral

examination. The final Phase III examinations include a

rapid film reporting examination, a dissertation, and an oral examination based on the dissertation project.

The rapid film reporting examination simulates the

typical day-to-day tasks of a radiologist, who has to

review numerous radiographs in a short time, particularly

in emergency medicine and general practice situations.[3]

The examination requires candidates to view several

radiographs within a specified amount of time and report

on the findings. In the Malaysian setting, candidates

need to report on 25 radiographs within 30 minutes.

For each film, they have to state whether it is normal or

abnormal; and if abnormal, then they have to describe the

abnormalities seen. The Royal College of Radiologists in

the United Kingdom has reported using rapid reporting

sessions as part of their examinations.[3]

The Board feels that, as part of the final-year high-stakes

exit examination, the rapid film reporting

examination also requires standard setting of its cut-off

score.

This article reports on a pilot study of standard setting

of the rapid film reporting examination of the Malaysian

National Conjoint Board of Radiology. To our

knowledge, there is no literature reporting on standard

setting of this particular method of assessment. We hope

this report will be useful for radiology postgraduate

training institutions employing similar assessment

modalities.

METHODS

A workshop to introduce members of the board to

standard-setting principles and practice was held in

April 2019. The workshop was organised with the help

of the Medical Education Department from one of the

participating universities.

A standard-setting meeting was organised before the

rapid film reporting examination in the exit examination

for Year 4 candidates in May 2019. It was chaired by one

of the authors, ILS.

An eight-step standard-setting planning process was

followed.[4]

Selection of a Standard-Setting Method

Modified Angoff is one of the standard-setting methods

that offers a systematic procedure in estimating

performance standard at the pass-fail level.[5] It has been

used in various high-stakes examinations as it offers the

best balance between technical adequacy and feasibility.[6]

The Modified Angoff method was selected for this

examination as it is an absolute standard-setting method — the candidates are judged against defined standards

rather than cohort performance. This is achieved by

asking qualified and trained judges to review test items

or prompts before the examination is administered.

Although the process can be time-consuming and labour-intensive,

it is relatively easier and more flexible than

other test-based methods. It is supported by a strong body

of evidence in the literature and has wide applicability to

many formats.[7]

In the modified Angoff method, judges review items

(questions) used in the assessment, discuss and agree on

the characteristics of a borderline candidate, and assess

the likely performance of borderline candidates for each

item. The mean of the judges’ estimates for all items is

taken as the cut-off score for that particular assessment.[4]

Selection of Judges

The selection of qualified judges is critical for an

absolute standard-setting method.[4] The following criteria

are recommended: content expertise, familiarity with the

target population, understanding of the task of judging

as well as the content materials, being fair and open-minded,

willingness to follow directions, lack of bias,

and willingness to devote their full attention to the task.

A total of 11 judges were chosen after considering the

above criteria.

Preparation of Descriptions of Performance

Categories

Judges need to have a clear understanding of the

performance categories, which are ‘narrative descriptions

of the minimally acceptable behaviours required in order

to be included in a given category’[4] to enable them to

distinguish between different levels of performance.

In licensing and certification situations, the focus is often

on discussion and description of a ‘borderline candidate’.[8]

Candidates who equal or exceed the performance of

these borderline candidates are then deemed ‘pass’ while

those who perform worse are deemed ‘fail’.

The group discussed the characteristics of a borderline

candidate in the setting of the Radiology Master of

Medicine course and agreed that: ‘A borderline candidate

of the exit examination should demonstrate basic

knowledge for safe clinical decision and management,

is able to work under minimal supervision, is equipped

with basic radiological skills and conducts himself/

herself professionally.’

Training of Judges

The definition of the borderline candidate appears

straightforward, but judges often find it difficult to

come up with an actual mark after reading a question

while thinking like a borderline student.[4] Judges need

familiarisation with the procedure and in generating

ratings. Training judges, therefore, is given priority and

can take more than one day.[9]

In our situation, apart from attending the introductory

workshop mentioned above, judges were also briefed by

the department chairperson at the beginning of the exercise.

The objectives, procedures for standard setting, and the

definition of a borderline candidate were discussed.

Collection of Ratings or Judgements

All 25 films used in the rapid film reporting examination,

together with the answers, were shown in the standard-setting

session. Each film was shown for 10 seconds

and judges were asked to individually decide, “Will a

borderline candidate be able to decide whether this film

is normal or abnormal? If abnormal, will they be able to

describe the abnormality in full?” Based on the answers

to these questions the judges calculated the scores

obtained by their hypothetical borderline candidates.

Judges then announced the scores verbally in turn and

their judgements were recorded immediately in a pre-prepared

Excel file by an assistant.

The rating of one film by judges and the collection

of their judgements was considered as one round of

standard setting.

Provision of Feedback and Facilitation of

Discussion

We included a discussion session after each round of

judgement. The completed spreadsheet was projected to

a screen where judges could see their standing relative

to the other judges. This ‘normative information’ helps

judges generate relevant and realistic cut-off scores.[8]

Ratings at the extreme ends were then discussed. A

second round of standard setting followed, where judges

were then allowed to revise their ratings. This step of

feedback and discussion followed by a second round of

ratings is known as an ‘iterative procedure’.[4]

Evaluation of the Standard-Setting

Procedure

There are three main sources of evidence to support

the validity of a standard-setting procedure: procedural

evidence, internal evidence, and external evidence.[4]

For procedural evidence, we reviewed the practicality

and implementation of the exercise and obtained

feedback from the judges involved. To this end, an

online questionnaire, taken from Yudkowsky et al[4] was

administered. It looked at judges’ perceptions of their

orientation, training, and implementation as well as their

confidence in the resulting cut-off scores.

Internal evidence was evaluated by calculating the inter-rater

reliability, the standard deviation of judge scores

(judgement SD), and the standard deviation of examinee

test scores (test SD). The judgement SD should be no

more than 25% of the test SD.[10]

Provision of Results, Consequences and

Validity Evidence to Decision-Makers

For the external evidence, we looked at the aspect of

reasonableness which is ‘…the degree to which cut-off

scores derived from the standard-setting process

classify examinees into groups in a manner consistent

with other information about the examinees’.[11] We

adapted the ‘diagnostic performance’ approach used

by Schoonheim-Klein et al[12] whereby two clinical

supervisors in each participating university were asked

to independently rate their candidates’ ability in rapid

reporting on a four-point scale: excellent, borderline

pass, borderline fail, and poor. The supervisors, who

observe their supervisees over a prolonged time period,

were guided by a rubric for each decision. To ensure

credible ratings, they were informed that their ratings were not a measure of supervision quality and would

not contribute to the candidates’ examination marks.

Candidates rated as ‘poor’ and ‘borderline fail’ were

grouped as ‘incompetent’, and those rated as ‘borderline

pass’ and ‘excellent’ were grouped as ‘competent’. This

clinical rating (considered as the ‘true qualification’)

was then compared with the pass-fail classification

obtained from the standard-setting method under study

to get the rate of ‘false positives’ and ‘false negatives’.

We also calculated the sensitivity and specificity for the

traditional and standard-setting–derived passing mark.

Sensitivity is defined as the ability of the standard-setting–

derived passing mark to correctly identify the

competent candidates or the true-positive rate. On the

other hand, specificity is defined as the ability of the

mark to correctly eliminate the incompetent candidates,

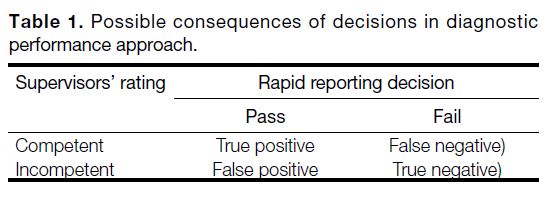

or true-negative rate. Table 1 summarises these concepts

and the formulas used to arrive at the decisions.

Table 1. Possible consequences of decisions in diagnostic

performance approach.

Provision of Results, Consequences and

Validity Evidence to Decision-Makers

Ultimately, policymakers set the standards, not the

judges.[8] As this is a pilot study, the validity data were

presented to the board to help decide on the adoption of

the standard-setting procedure.

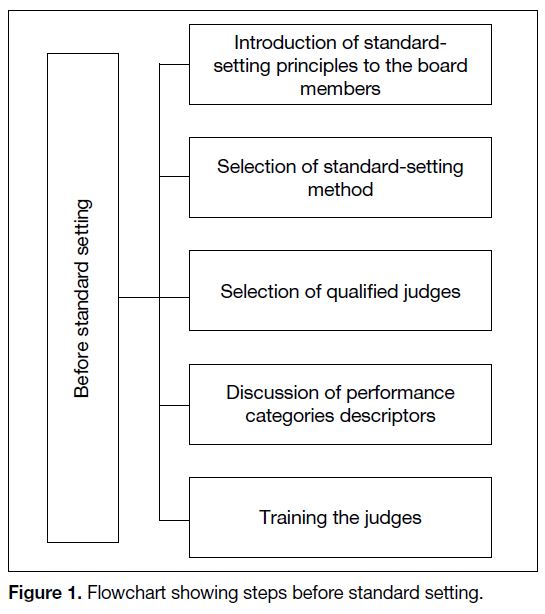

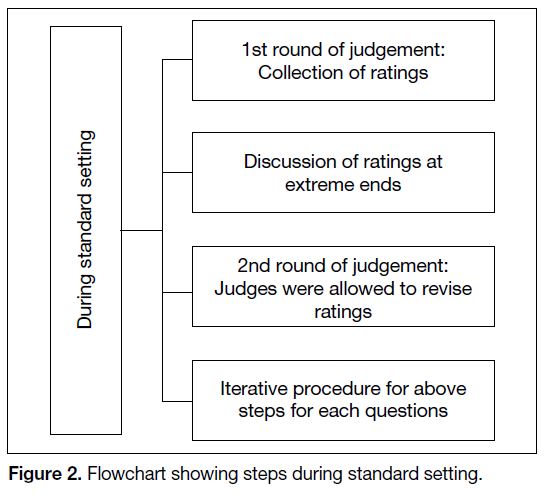

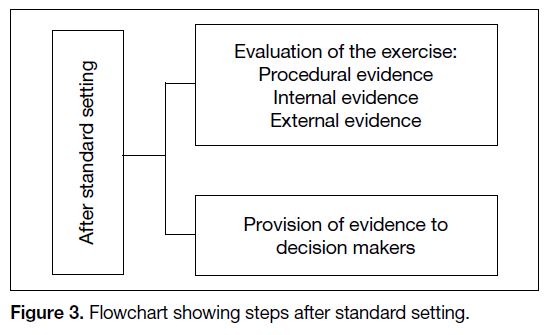

A summary of these procedures is given as steps before

(Figure 1), during (Figure 2) and after (Figure 3) the

standard-setting procedure.

Figure 1. Flowchart showing steps before standard setting.

Figure 2. Flowchart showing steps during standard setting.

Figure 3. Flowchart showing steps after standard setting.

RESULTS

Procedural Evidence

A cut-off score of 0.95 (95%) was obtained for the

first round, and 0.92 (92%) for the second round. The

traditional passing mark of the rapid film reporting was

80%.

Eleven judges provided feedback via the online

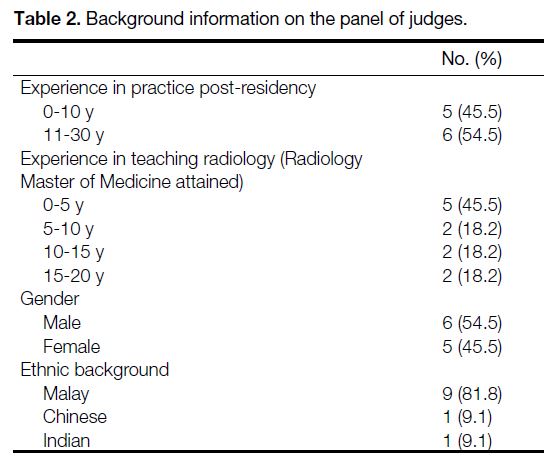

questionnaire. The panel was comprised of an almost

equal number of junior (<10 years of post-residency

practice and <5 years of involvement in teaching the

Radiology Master of Medicine course) and senior members. The same can be said of gender distribution.

The majority of panel members were ethnic Malay

(Table 2).

Table 2. Background information on the panel of judges.

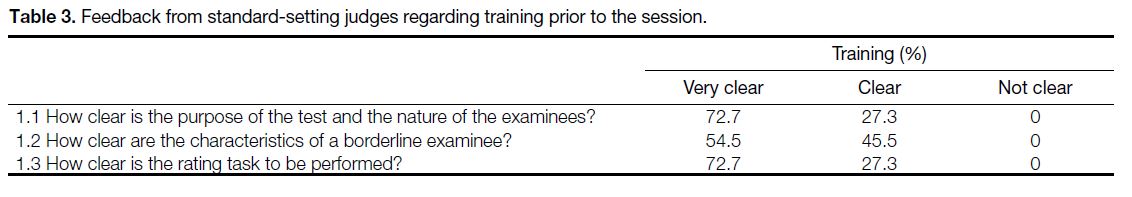

As regards feedback from judges about the training

and orientation that was provided before the session,

judges were generally clear about the purpose of the

test, the nature of the examinees, the characteristics of a

borderline candidate, and the rating task to be performed

(Table 3).

Table 3. Feedback from standard-setting judges regarding training prior to the session.

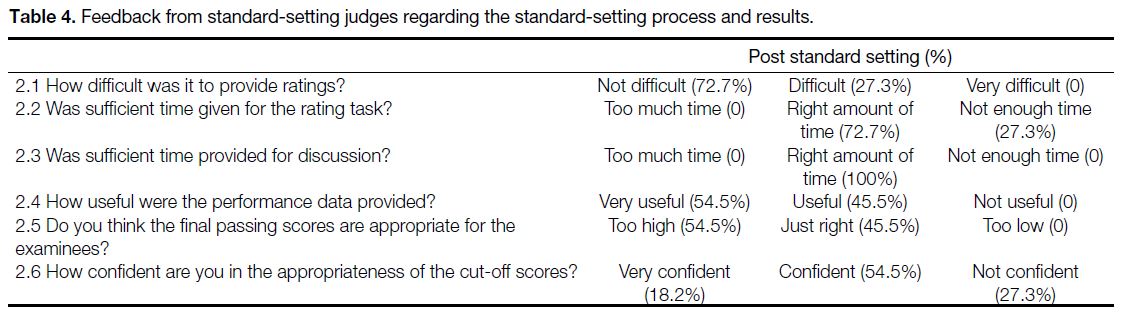

In terms of feedback from judges regarding the process

of standard setting, the majority were positive (Table 4).

Interesting points to note included the time given for

the rating task, where a minority (27.3%) felt that it

was insufficient. Slightly over half (54.5%) of judges

thought that the final passing score of 92% was too high.

A minority (27.3%) were not confident regarding the

appropriateness of the cut-off score.

Table 4. Feedback from standard-setting judges regarding the standard-setting process and results.

Internal Evidence

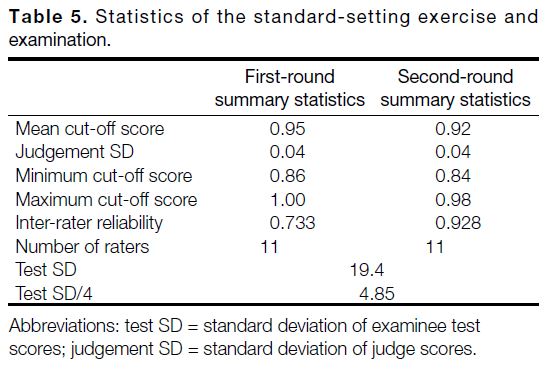

As stated above, cut-off scores of 0.95 and 0.92 were

obtained in the first and second rounds, respectively

(Table 5). The judgement SD was 0.04 on both rounds

while the test SD was 19.4. Inter-rater reliability

was 0.733 and 0.928 for the first and second rounds,

respectively.

Table 5. Statistics of the standard-setting exercise and examination.

External Evidence

As the ‘diagnostic performance approach’ assumes the

supervisors’ rating to be the gold standard, we calculated

the inter-rater reliability of the two supervisors. Cohen’s

kappa revealed a good agreement between the two

supervisors at κ = 0.780, p < 0.001.

The supervisors’ rating classified 24 candidates as

‘competent’ and three candidates as ‘incompetent’. As

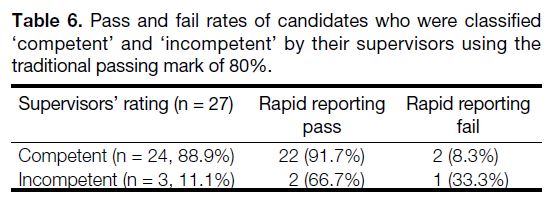

illustrated in Table 6, the traditional passing score of

80% resulted in a passing rate of 91.7% and a failure rate

of 8.3% among competent candidates. It is interesting

to note the occurrence of false-positives, where two

incompetent candidates passed the assessment. Only one

out of three incompetent candidates failed the assessment

using the traditional passing score. The sensitivity and

specificity for this passing score were found to be at 0.92

and 0.33, respectively.

Table 6. Pass and fail rates of candidates who were classified

‘competent’ and ‘incompetent’ by their supervisors using the traditional passing mark of 80%.

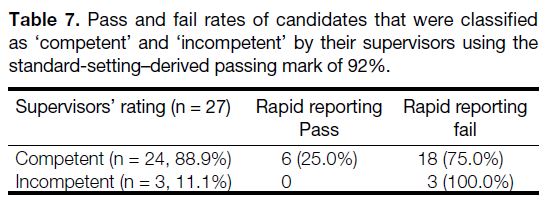

On the other hand, as per Table 7, using the standard-setting–

derived passing score of 92% resulted in a

25% passing rate among competent candidates. No incompetent candidates passed the assessment but there

was a high false-negative occurrence where 75% of

competent candidates failed the assessment. All three

incompetent candidates failed the assessment. This gives

this passing score a sensitivity of 0.25 and specificity of

1.00.

Table 7. Pass and fail rates of candidates that were classified

as ‘competent’ and ‘incompetent’ by their supervisors using the standard-setting–derived passing mark of 92%.

DISCUSSION

The main aim of this pilot study was to assess the

validity of the standard-setting procedure for the rapid

film reporting examination. The current concept of validity is the accumulation of evidence to support or

refute a particular interpretation or use of examination

data.[13] In the context of standard setting, we looked at

the procedural, internal, and external evidence to support

the validity of our rapid film reporting standard-setting

exercise[8] and generally found the results encouraging.

Procedurally, the process was feasible and practical.

No major hurdles were encountered in the planning

as well as preparation of the standard-setting exercise,

including the physical setting. The positive responses

from judges regarding implementation of points raised

in the questionnaire provided additional evidence of the

credibility of the standard-setting process.[8]

We take note that thorough and meticulous documentation

of the procedure is critical.[9] This includes the summary

of judges’ background information, which includes

speciality and teaching experience, as shown in Table 2.

The background and experiential composition of

the judges’ panel should be determined before their

nomination.[9]

It is interesting to note that slightly more than half of the

judges (54.5%) believed that the cut-off score obtained

was too high. Despite that, only 27.3% of judges were

not confident of the cut-off score obtained. We need to

differentiate between the perception of judges that the

cut-off score is high from actual unrealistically high

cut-off scores. The clarity of the judges regarding their

role and the nature of the candidates, as well as their

confidence in the cut-off score, are more in favour of the

former. The latter is noted to happen in many standardsetting

situations, particularly using the Angoff method

when judges are not given performance data.[4]

Still, the issue of producing a cut-off score that is too high

needs to be addressed, as it may hinder the acceptance of

standard setting in the future. One approach is to increase

the quality and efficiency of all the eight steps of standard

setting described in the methodology, especially the types

of feedback given to the judges during step 6 (Provision

of Feedback and Facilitation of Discussion). In our case,

the judges’ relative standing to each other, known as

normative information, were revealed following the first

round. The literature also describes providing judges

with information about actual candidate performance

on each item (reality information) and the consequences

of the generated cut-off scores (impact information).[8]

To have these kinds of information available, however,

requires the standard-setting procedure to be done after the actual examination. Another approach is to adjust the

cut-off score using the standard error of measurement of

the test. If false-negative decisions (failing competent

candidates) are of concern, then the cut-off score can be

lowered by one standard error of measurement.[4]

The internal evidence of validity includes the high inter-rater

reliability of the judgements, which was 0.733 for

the first round and 0.928 for the second round. Reliability

≥0.9 is needed for very-high-stakes examinations.[14] It is

worth noting that the reliability increased from 0.7 to 0.9

in the second round, supporting the value of the iterative

procedure in standard setting.

The judgement SD was small (0.04), less than the

recommended limit, which is 25% of the standard

deviation of the examinee test scores[10]; in this case,

4.85. Several factors may have contributed to this. One

is that all films to be used for the examination were

standardised in the session, instead of just sampling some

films. Another possible factor is the adequate number of

judges, 11 in this case. The recommended number is 10

to 12 judges.[4]

The sensitivity and specificity testing has shown the

value of standard setting in establishing consequential

validity evidence, discussed as part of ‘reasonableness’

in standard-setting literature.[9] In this exercise, using

the traditional passing mark of 80% resulted in three

incompetent candidates passing the assessment. For

high-stakes assessment such as the exit examination,

high specificity is considered to be more important

than high sensitivity. This is because re-examination

can correct the false-negative occurrences but not the

false-positive candidates who may practise unsafely

below the desired standards.[12] However, as judges have

been shown to naturally produce higher passing scores

in Angoff exercises, future practice could improve with

more training sessions, a more detailed discussion of the

borderline standards, and using performance data during

the judging process as a control measure.[12] [15] [16]

CONCLUSION

In summary, we are encouraged by the findings of

this standard-setting feasibility study of the rapid film

reporting examination. It appears feasible and seems to

have good procedural, internal, and external validity.

Areas of potential improvement include more judge

training and providing more feedback data to judges. We

look forward to its official implementation in the near

future.

REFERENCES

1. Epstein RM. Assessment in medical education. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:387-96. Crossref

2. Beckman TJ, Cook DA, Mandrekar JN. What is the validity

evidence for assessments of clinical teaching? J Gen Intern Med.

2005;20:1159-64. Crossref

3. Booth TC, Martins RD, McKnight L, Courtney K, Malliwal R.

The Fellowship of the Royal College of Radiologists (FRCR)

examination: a review of the evidence. Clin Radiol. 2018;73:992-8. Crossref

4. Yudkowsky R, Downing SM, Tekian A. Standard Setting. In:

Yudkowsky R, Park YS, Downing SM, editors. Assessment in

Health Professions Education. 2nd ed. New York: Routledge; 2020:

p 86-105. Crossref

5. Shulruf B, Wilkinson T, Weller J, Jones P, Poole P. Insights into

the Angoff method: results from a simulation study. BMC Med

Educ. 2016;16:134. Crossref

6. Cizek GJ, Bunch MB. The Angoff method and Angoff variations.

In: Cizek GJ, Bunch MB, editors. Standard Setting. California:

Sage Publications; 2011: p 81-95.

7. Plake BS, Cizek GJ. Variations on a theme. ¬The modified Angoff,

extended Angoff and Yes/No standard setting methods. In: Cizek

GJ, editor. Setting Performance Standards: Foundations, Methods,

and Innovations. 2nd ed. New York: Routledge; 2012: p 181-99.

8. Cizek GJ, Earnest DS. Setting performance standards on tests. In:

Lane S, Raymond MR, Haladyna TM, editors. Handbook of Test

Development. 2nd ed. New York: Routledge; 2016; p 212-37.

9. Hambleton RK, Pitoniak MJ, Coppella JM. Essential steps in

setting performance standards on educational tests and strategies

for assessing the reliability of results. In: Cizek GJ, editor. Setting

Performance Standards: Foundations, Methods, and Innovations.

2nd ed. New York: Routledge; 2012: p 47-76.

10. Meskauskas JA. Setting standards for credentialing examinations:

an update. Eval Health Prof. 1986;9:187-203. Crossref

11. Cizek GJ. The forms and functions of evaluations in the standard

setting process. In: Cizek GJ, editor. Setting Performance

Standards: Foundations, Methods, and Innovations. 2nd ed. New

York: Routledge; 2012; p 165-78. Crossref

12. Schoonheim-Klein M, Muijtjens A, Habets L, Manogue M, van

der Vleuten C, van der Velden U. Who will pass the dental OSCE?

Comparison of the Angoff and the borderline regression standard

setting methods. Eur J Dent Educ. 2009;13:162-71. Crossref

13. Downing SM. Validity: on the meaningful interpretation of

assessment data. Med Educ. 2003;37:830-7. Crossref

14. Axelson RD, Kreiter CD. Rater and occasion impacts on the

reliability of pre-admission assessments. Med Educ. 2009;43:1198-202. Crossref

15. Kane MT, Crooks TJ, Cohen AS. Designing and evaluating

standard-setting procedures for licensure and certification tests.

Adv Heal Sci Educ Theory Pract. 1999;4:195-207. Crossref

16. Kramer A, Muijtjens A, Jansen K, Düsman H, Tan L, van der Vleuten C. Comparison of a rational and an empirical standard

setting procedure for an OSCE. Objective structured clinical

examinations. Med Educ. 2003;37:132-9. Crossref

| Attachment | Size |

|---|---|

| v24n1_Setting.pdf | 486.74 KB |