Imaging Findings and Clinical Perspectives of Acute Necrotising Encephalopathy: Report of Two Cases

CASE REPORT

Imaging Findings and Clinical Perspectives of Acute Necrotising Encephalopathy: Report of Two Cases

HL Wong, HY Lau, JCW Siu

Department of Radiology, Tuen Mun Hospital, Tuen Mun, Hong Kong

Correspondence: Dr HL Wong, Department of Radiology, Tuen Mun Hospital, Tuen Mun, Hong Kong. Email: holimw@gmail.com

Submitted: 2 Dec 2019; Accepted: 10 Dec 2019.

Contributors: JCWS designed the study. HLW acquired and analysed the data, and drafted the manuscript. JCWS and HYL critically revised the

manuscript for important intellectual content.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Funding/Support: This case report received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics Approval: The patients were treated in accordance with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. The patients provided written informed

consent for all treatments and procedures.

INTRODUCTION

First coined by Mizuguchi[1] in 1997, acute necrotising

encephalopathy (ANE) is a severe, uncommon type of

encephalopathy with distinctive imaging and clinical

features and a global distribution. Despite ongoing

studies, the exact pathogenesis of ANE is yet to be

determined and is still classified as an idiopathic disorder.

It is hypothesised that the disease is an immune response

to a prior, mostly viral, infection. With two illustrative

cases, we showcase the current understanding of the

pathogenesis, clinical and radiological presentation of

the disease as well as the latest treatment strategies.

CASE 1

A 2-year-old boy with good past health developed fever

and upper respiratory symptoms for 1 day. His symptoms

deteriorated overnight and he developed generalised

seizure. He was then urgently admitted to the Accident

and Emergency Department where the seizure was

aborted with anticonvulsant therapy. He was transferred

to the paediatric intensive care unit for further care.

A nasopharyngeal swab for rapid antigen test was

positive for influenza A. Despite empirical treatment

with vancomycin, rocephin, acyclovir, and oseltamivir,

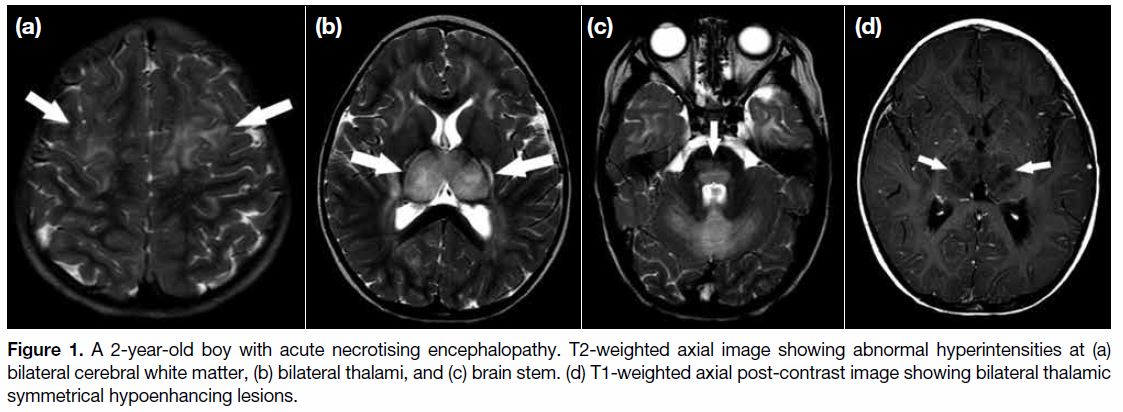

the patient developed breakthrough seizure. An urgent contrast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed

symmetrical T2 and fluid attenuated inversion recovery

hyperintensities with restricted diffusion over bilateral

thalami, white matter, and brain stem (Figure 1a-c).

Bilateral thalami were markedly swollen with central

hypo-enhancement (Figure 1d). Features were suggestive

of ANE.

Figure 1. A 2-year-old boy with acute necrotising encephalopathy. T2-weighted axial image showing abnormal hyperintensities at (a)

bilateral cerebral white matter, (b) bilateral thalami, and (c) brain stem. (d) T1-weighted axial post-contrast image showing bilateral thalamic

symmetrical hypoenhancing lesions.

The patient was started on intravenous pulse steroid

but his neurological condition deteriorated rapidly. A

follow-up computed tomography (CT) scan of the brain

showed diffuse cerebral oedema with effacement of

bilateral cerebral sulci and cisterns. Evidence of coning

was also observed. An urgent bilateral craniotomy and

decompression were performed. Despite the surgical

management, the patient’s condition remained poor.

Neurologically, the patient showed minimal brain

stem response and scored 4 (E1V1M2) in the Glasgow

Coma Scale. On day 5 after admission, the patient

succumbed.

CASE 2

A 6-year-old boy with good past health presented with

high fever, upper respiratory symptoms and transient

episodes of confusion. An urgent CT scan of the brain

performed on admission revealed no abnormality. A rapid antigen test on nasopharyngeal swab was positive

for influenza A.

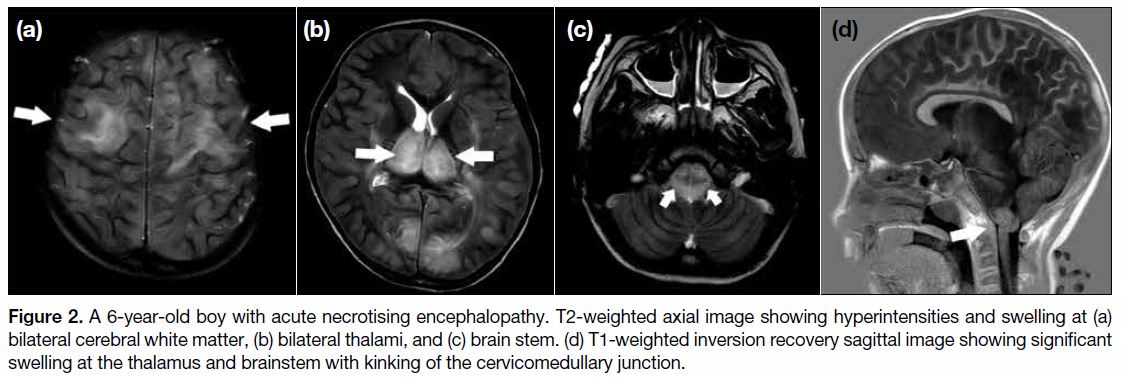

The patient’s level of consciousness deteriorated rapidly:

Glasgow Coma Scale score dropped from 15 to 4 over 7

hours. MRI performed 12 hours after admission revealed

bilateral symmetrical T2 hyperintensities in the thalamus

and brain stem (Figure 2a and b). Associated bilateral

cerebral and cerebellar white matter hyperintensities

were also observed (Figure 2c). Features were suggestive

of ANE. There was significant swelling at the thalamus

and brain stem with kinking of the cervicomedullary

junction (Figure 2d). Crowding of the foramen magnum

was evident.

Figure 2. A 6-year-old boy with acute necrotising encephalopathy. T2-weighted axial image showing hyperintensities and swelling at (a)

bilateral cerebral white matter, (b) bilateral thalami, and (c) brain stem. (d) T1-weighted inversion recovery sagittal image showing significant

swelling at the thalamus and brainstem with kinking of the cervicomedullary junction.

A neurosurgical opinion was sought and the boy was

deemed too ill to benefit from surgery. He remained

comatose with no obvious return of any brainstem

function despite all medical support. The patient was

certified dead on day 12 after admission.

DISCUSSION

Pathogenesis and Aetiology of Acute

Necrotising Encephalopathy

The most widely accepted cause of ANE is

hypercytokinaemia.[2] Patients with ANE mount

an exaggerated immune response to infection by

releasing a high level of cytokines. There is evidence

that the level of various inflammatory mediators,

including different interleukins (IL-6, IL-15, IL-1β,

IL-10), tumour necrosis factor-α as well as interferon-γ,[2] [3] [4]

is raised in the serum as well as the cerebrospinal fluid.

This causes multiple system failure.[1]

Both environmental and host factors seem to play a role

in a predisposition to ANE.

A number of different infections are associated with

ANE and different pathogens have been reported,

including viruses and bacteria.[2] [5] Influenza virus is the

most common culprit.

There have been some recurrent cases reported within

certain families, suggesting a genetic predisposition.[5]

In recurrent cases, missense mutations in Ran-binding

protein 2 were identified as the susceptibility alleles.[5]

Clinical Presentation of Acute Necrotising

Encephalopathy

In general, the clinical presentation of ANE can be

classified into three stages: the prodromal stage, the

acute encephalopathy stage, and the recovery stage.

The presentation in the prodromal stage is highly

variable, due to the wide range of antecedent pathogens

possible. Symptoms may include fever, upper respiratory

symptoms, gastroenteritis, or skin rashes. Patients with

ANE may also present with more severe symptoms

including shock, disseminated intravascular coagulation

and even multiple organ failure.[5]

As the disease progresses, the acute encephalopathy

stage ensues during which neurological symptoms

will manifest rapidly. Seizures, an altered level of

consciousness and focal neurological deficits may

occur. The patient usually requires intensive care

support.

Although majority of the cases result in high morbidity

and mortality, milder forms with recovery have also

been reported.[5]

Radiological Findings and Imaging

Differential Diagnoses of Acute Necrotising

Encephalopathy

Contrary to the highly non-specific clinical presentations,

imaging features of ANE can usually help to narrow

down the differential diagnosis.[5] The list of differential

diagnoses is limited when rapid neurological deterioration

is taken into account.

The typical imaging presentation of ANE is multiple

symmetrical lesions with supra- and infra-tentorial brain

involvement. The thalami, brain stem, cerebral white

matter, and cerebellum[1] [2] are typical sites of involvement.

Spinal cord involvement is also occasionally reported.[5]

Among them, bilateral thalami involvement is the most

distinctive feature of ANE.[1]

It is also common for imaging features of ANE to change

over the clinical course.[1] [5] Significant oedema is seen

in the early phase. On CT, the lesions will show up as

symmetrical hypodense foci with mass effect. On MRI, the lesions will have a low T1 signal and high T2 signal.

There will also be fluid restriction on diffusion-weighted

imaging and apparent diffusion coefficient.[5]

As the disease progresses, imaging features change.

Oedema will subside and features of petechial

haemorrhage and necrosis may appear. On CT, this will

appear as new heterogeneous hyperdense foci within the

previously seen hypodensities.[1] [5] On MRI T1-weighted

image, there will be new hyperintensities within the

pre-existing hypointense lesions, while on T2-weighted

image they will show up as a hypointense centre

surrounded by a high signal rim.[5] Susceptibility weight

images and T2* gradient echo imaging are more able

to show the petechial haemorrhage that will appear as

low signal foci with blooming artefact.[5] The classically

described ANE imaging features of concentric structures,

tricolour pattern, or target-like appearance can be seen

on apparent diffusion coefficient images. The centre

of the lesion shows high signal with a hypointense rim

suggesting cytotoxic oedema. A further outer rim of

hyperintensity suggests vasogenic oedema.[5] [6]

With specific imaging features of ANE and a rapid

neurological decline, the imaging differential diagnoses

of ANE are limited. Entities that need to be considered

include acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, Reye’s

syndrome and Leigh’s syndrome. Acute disseminated

encephalomyelitis is associated with multiple bilateral

brain lesions bilaterally. Nonetheless the lesions do

not typically affect the brain symmetrically as in ANE.

Although Reye’s syndrome and Leigh’s syndrome may

present with symmetrical brain lesions, both entities are

characterised by the presence of lactic acidosis.

In both of our cases, the later imaging features were

not well demonstrated due to the rapid clinical course.

Unfortunately both patients succumbed before follow-up

imaging was available. However, the typical early

imaging features of ANE were well demonstrated.

Diagnostic Criteria of Acute Necrotising

Encephalopathy

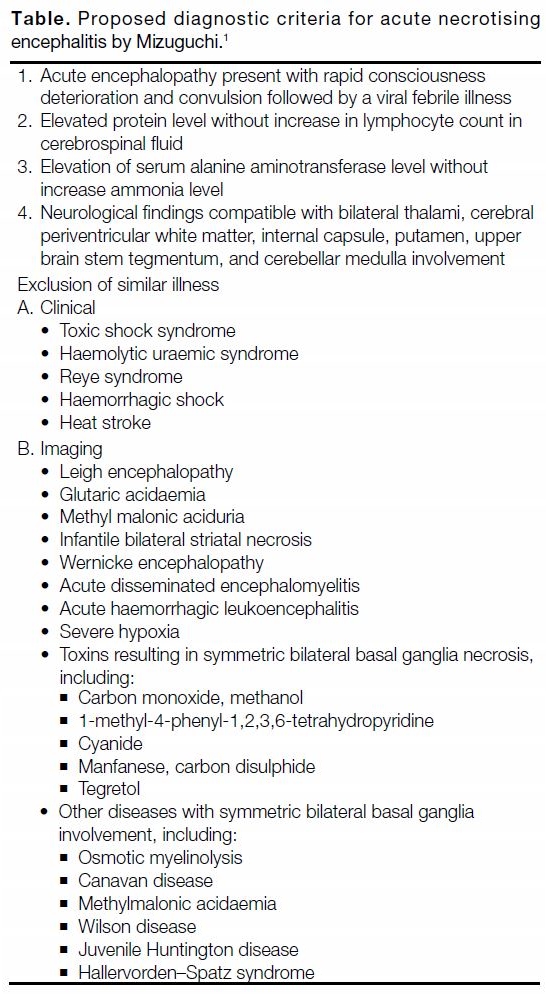

Diagnosis of ANE is made if both clinical and imaging

findings are present and when similar-presenting

diseases have been excluded. Mizuguchi[1] have outlined

the diagnostic criteria (Table).

Table. Proposed diagnostic criteria for acute necrotising

encephalitis by Mizuguchi.[1]

Management and Prognosis of Acute

Necrotising Encephalopathy

There is no definitive recommended treatment for ANE. The mainstay of treatment is intensive care and

symptomatic treatment.

Theoretically, intravenous steroids, immunoglobulin,

and plasmapheresis should be effective in view of the

postulated immunological aetiology.[5] [7] High-dose

steroid is the most widely documented treatment.

Administration of steroids within 24 hours of symptom

onset is proposed to be related to an improved outcome.[5]

Therapeutic hypothermia has also been mentioned as a

supportive treatment.[5]

Despite treatment, ANE has a grave prognosis. The

mortality rate is reported to be about 30%. Complete

neurological recovery is observed in fewer than 10%

of patients and many survivors develop long-term

neurological sequelae.[1] [5]

CONCLUSION

Acute necrotising encephalitis is a severe neurological

complication of a common infection. The exact

pathogenesis is incompletely understood. The prognosis

of ANE is generally poor, although recent studies have

shown that starting treatment early may have a great

impact on the final outcome. Prompt diagnosis is vital to

ensure early treatment. The diagnosis of ANE is mainly

based on clinical and radiological features after exclusion

of other diseases with similar presentation.

The two cases we describe had typical imaging findings

and clinical presentation. One important limitation of our

case sharing is a lack of radio-pathological correlation.

In both patients, the cause of death was stated as ANE

and autopsy was waived in the absence of any other

suspected cause.

REFERENCES

1. Mizuguchi M. Acute necrotizing encephalopathy of childhood: a

novel form of acute encephalopathy prevalent in Japan and Taiwan.

Brain Dev. 1997;19:81-92. Crossref

2. Munakata M, Kato R, Yokoyama H, Haginoya K, Tanaka Y,

Kayaba J, et al. Combined therapy with hypothermia and

anticytokine agents in influenza A encephalopathy. Brain Dev

2000;22:373-7. Crossref

3. Tabarki B, Thabet F, Al Shafi S, Al Adwani N, Chehab M,

Al Shahwan S. Acute necrotizing encephalopathy associated with

enterovirus infection. Brain Dev. 2013;35:454-7. Crossref

4. Vargas WS, Merchant S, Solomon G. Favorable outcomes in acute

necrotizing encephalopathy in a child treated with hypothermia.

Pediatr Neurol. 2012;46:387-9. Crossref

5. Wu X, Wu W, Pan W, Wu L, Liiu K, Zhang HL. Acute necrotizing

encephalopathy: an underrecognized clinicoradiologic disorder.

Mediators Inflam. 2015;2015:792578. Crossref

6. Ohsaka M, Houkin K, Takigami M, Koyanagi I. Acute necrotizing

encephalopathy associated with human herpesvirus-6 infection.

Pediatr Neurol. 2006;34:160-3. Crossref

7. Skelton BW, Hollingshead MC, Sledd AT, Philips CD, Castillo M.

Acute necrotizing encephalopathy of childhood: typical findings in

an atypical disease. Pediatr Radiol. 2008;38:810-3. Crossref

| Attachment | Size |

|---|---|

| v23n4_Imaging.pdf | 242.73 KB |