Local and Regional Staging of Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma Using Magnetic Resonance Imaging

PICTORIAL ESSAY

Local and Regional Staging of Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma Using Magnetic Resonance Imaging

KY Chan, JCW Siu

Department of Radiology, Tuen Mun Hospital, Tuen Mun, Hong Kong

Correspondence: Dr KY Chan, Department of Radiology, Tuen Mun Hospital, Tuen Mun, Hong Kong. Email: andrew_yuk@msn.com

Submitted: 15 Jan 2019; Accepted: 21 Mar 2019.

Contributors: KYC designed the study, acquired the data, and drafted the manuscript. All authors analysed and interpreted the data and critically

revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors had full access to the data, approved the final version for publication, and

take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding/Support: This pictorial essay received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics Approval: This study was approved by the New Territories West Cluster Research Ethics Committee (Ref NTWC/REC/19113).

BACKGROUND

Nasopharyngeal carcinoma is the most common cancer

originating from the nasopharynx. The tumour accounts

for up to 70% of all primary malignant lesions arising

from the nasopharynx.[1] [2] Most cases are seen in adults

with the disease rare in the paediatric population. The

peak incidence occurs between age 40 and 60 years. The

disease is prevalent in southern China, with most cases

located in Guangdong, Guangxi, and Fujian provinces.[3]

The disease is relatively rare in Western populations.

The disease is more prevalent among men than women,

with the incidence in men up to 3 times that of women,[4]

regardless of geographic location.

Multiple aetiologies have been postulated in the

development of nasopharyngeal carcinoma. The first is

viral: the Epstein-Barr virus shows a strong association

in some cases of nasopharyngeal carcinoma.[5] A positive

correlation for level of antibodies to Epstein-Barr virus

(EBV) with size of tumour has been demonstrated, with

the former used to monitor disease status and response

to therapy. Recently, human papilloma virus has been

shown to have an association with non-endemic EBV

negative cases of nasopharyngeal carcinoma. These

cases demonstrate a worse outcome than EBV positive

cases.[6] A second aetiology is related to environmental factors. Chinese-style salted fish and other preserved

foods contain high levels of volatile nitrosamine, a

carcinogen that contributes to the development of many

cases of nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Other environmental

factors include smoking and cooking. Genetics also play

a role in the development of nasopharyngeal carcinoma:

multiple human leukocyte antigens have been shown to

have a causative effect.[7]

Similar to many other squamous cell carcinomas in the

head and neck region, the TNM staging system is applied

in nasopharyngeal carcinoma.[8] [9] This pictorial essay

focuses on different stages of nasopharyngeal carcinoma

according to the latest guideline from the American Joint

Committee on Cancer (AJCC) 8th edition, that has been

recommended and implemented since 1 January 2018.[8] [9]

Comment is made about revisions made since the 7th

edition. A series of nasopharyngeal carcinoma cases of

various stages was retrieved from the reporting system

of the Department of Radiology at Tuen Mun Hospital.

IMAGING FINDINGS

The typical appearance of nasopharyngeal carcinoma

is that of a T1 isointense and T2 isointense/mildly

hyperintense lesion with reference to the adjacent

muscles. It usually shows heterogeneous contrast enhancement following injection of gadolinium contrast,

particularly useful when evaluating perineural spread of

the disease. For both T1 post-contrast and T2-weighted

sequences, a fat saturation technique is usually employed

to improve visualisation of the tumour.[10]

T STAGE

Detailed descriptions of the local staging of tumours can

be found in the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual.[9]

TX or T0

TX indicates that the primary tumour is too small or

inconspicuous to be visualised on imaging. T0 is a

new addition to the AJCC 8th edition, and describes no

conspicuous primary tumour detected despite positive

EBV involvement of cervical lymph nodes.[11] It is

relatively uncommon among different T stages owing to

the high sensitivity of magnetic resonance imaging.[12]

T1 Disease

T1 disease indicates that the tumour is confined to the

nasopharynx, or has extended to the oropharynx and/or

nasal cavity without parapharyngeal involvement.[9] The

nasopharynx is defined as the most superior part of the

pharynx. Inferiorly, it continues as the oropharynx and

anteriorly as the nasal cavity through the choana. On

its superior aspect, it is bound by the basisphenoid and

basiocciput that form the roof of the nasopharynx. On the

bilateral lateral aspects of the nasopharynx, there is focal

insinuation of mucosa to form an indentation called the

fossa of Rosenmüller, a.k.a. lateral recess. It is the most

common site of origin for nasopharyngeal carcinoma.[13]

The fossa of Rosenmüller lies posterior to the opening of the eustachian tube, and torus tubarius, an elevation

at the base of the cartilaginous portion of the eustachian

tube. There is no involvement of adjacent prevertebral

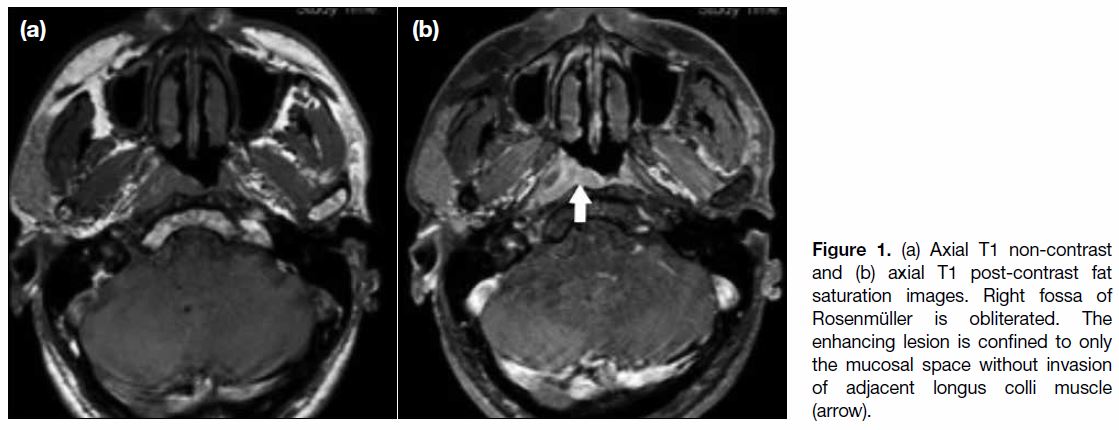

muscle or parapharyngeal space in T1 disease (Figure 1).

Figure 1. (a) Axial T1 non-contrast and (b) axial T1 post-contrast fat saturation images. Right fossa of Rosenmüller is obliterated. The enhancing lesion is confined to only the mucosal space without invasion of adjacent longus colli muscle (arrow).

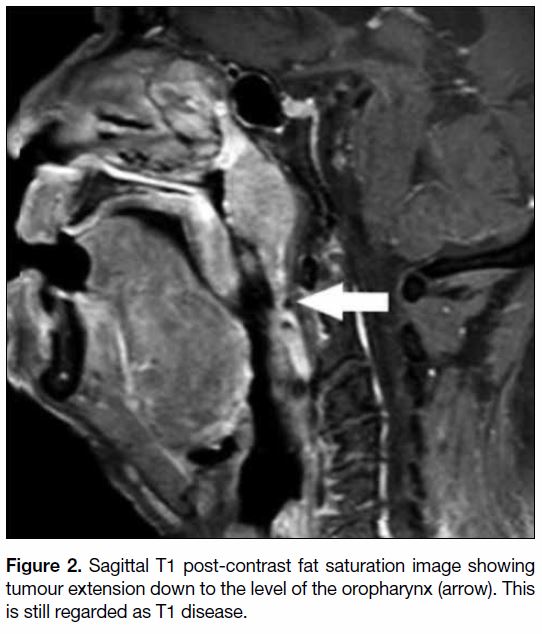

Nasopharyngeal carcinoma tends to spread upwards

rather than inferiorly to the oropharynx,[12] [14] although

involvement of the oropharynx is still denoted as T1

disease (Figure 2). The boundary of the nasopharynx and oropharynx is defined according to the level of the

soft palate. Solitary involvement of the oropharynx is

uncommon as the tumour tends to spread upwards and

laterally to the parapharyngeal space.[12] [14] Nasopharyngeal

tumour extending to the nasal cavity or oropharynx but

not the parapharyngeal space has no significantly worse

outcome than tumours confined to the nasopharynx. As

such they are both categorised as T1 disease.

Figure 2. Sagittal T1 post-contrast fat saturation image showing tumour extension down to the level of the oropharynx (arrow). This

is still regarded as T1 disease.

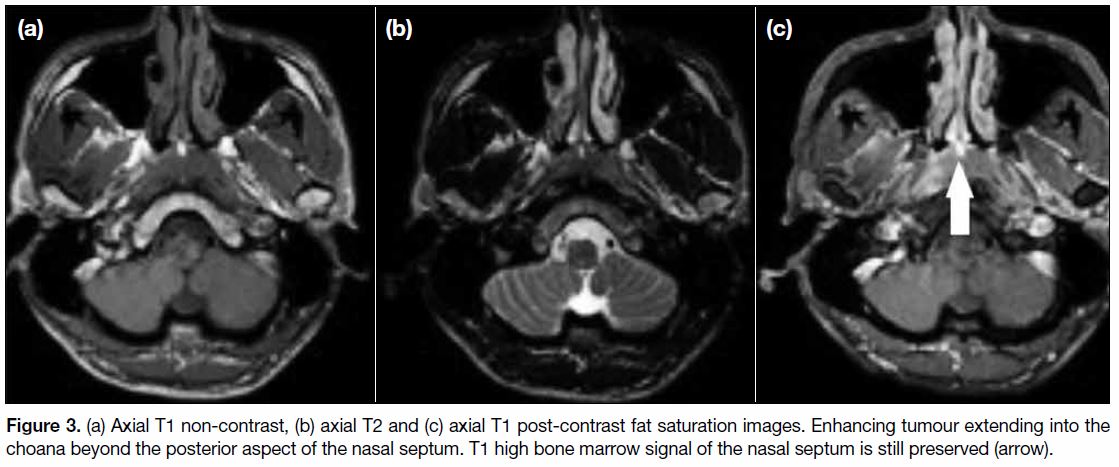

If the tumour extends beyond the choana, it enters the

nasal cavity. Usually there is only minimal extension

through the choana (Figure 3) and bulky tumour growth

within the nasal cavity is relatively uncommon.[12]

Expansion of the nasal cavity may be noted without definite invasion of underlying osseous structure as

evidenced by the preserved T1 fatty signal.[10]

Figure 3. (a) Axial T1 non-contrast, (b) axial T2 and (c) axial T1 post-contrast fat saturation images. Enhancing tumour extending into the

choana beyond the posterior aspect of the nasal septum. T1 high bone marrow signal of the nasal septum is still preserved (arrow).

The criteria for T1 disease in the AJCC 8th edition are

unchanged from the 7th edition.

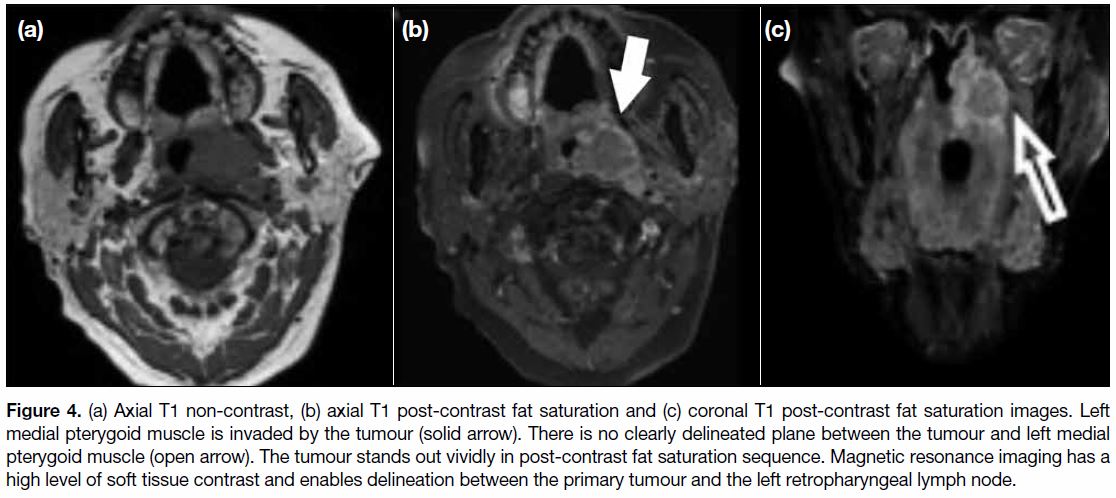

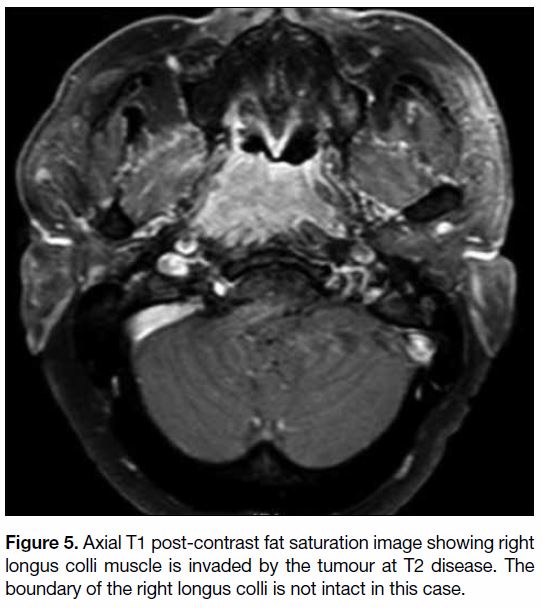

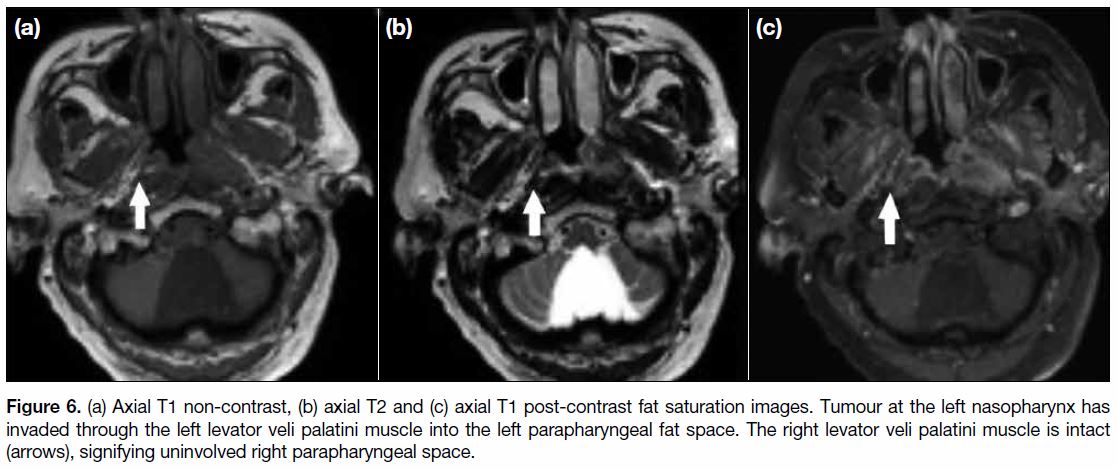

T2 Disease

T2 disease is defined as tumour with extension into

the parapharyngeal space, and/or adjacent soft tissue

involvement including medial pterygoid (Figure 4),

lateral pterygoid and prevertebral muscle (Figure 5).[9]

In the AJCC 7th edition, involvement of the pterygoid

muscles was denoted as T4 disease.[11] The medial aspect

of the parapharyngeal space is bound by the levator veli palatini muscle that is an elevator muscle of the soft

palate. When the tumour invades through this muscle

laterally and the pharyngobasilar fascia (the submucosal

layer between mucosa and muscular layer) into the fatty

parapharyngeal space, it is categorised as T2 disease

(Figure 6). When the tumour invades the parapharyngeal

space, structures such as the ascending pharyngeal

artery, lymph nodes, part of pterygoid venous plexus and

branches of the trigeminal nerve may be affected.[15]

Figure 4. (a) Axial T1 non-contrast, (b) axial T1 post-contrast fat saturation and (c) coronal T1 post-contrast fat saturation images. Left

medial pterygoid muscle is invaded by the tumour (solid arrow). There is no clearly delineated plane between the tumour and left medial

pterygoid muscle (open arrow). The tumour stands out vividly in post-contrast fat saturation sequence. Magnetic resonance imaging has a

high level of soft tissue contrast and enables delineation between the primary tumour and the left retropharyngeal lymph node.

Figure 5. Axial T1 post-contrast fat saturation image showing right

longus colli muscle is invaded by the tumour at T2 disease. The

boundary of the right longus colli is not intact in this case.

Figure 6. (a) Axial T1 non-contrast, (b) axial T2 and (c) axial T1 post-contrast fat saturation images. Tumour at the left nasopharynx has

invaded through the left levator veli palatini muscle into the left parapharyngeal fat space. The right levator veli palatini muscle is intact

(arrows), signifying uninvolved right parapharyngeal space.

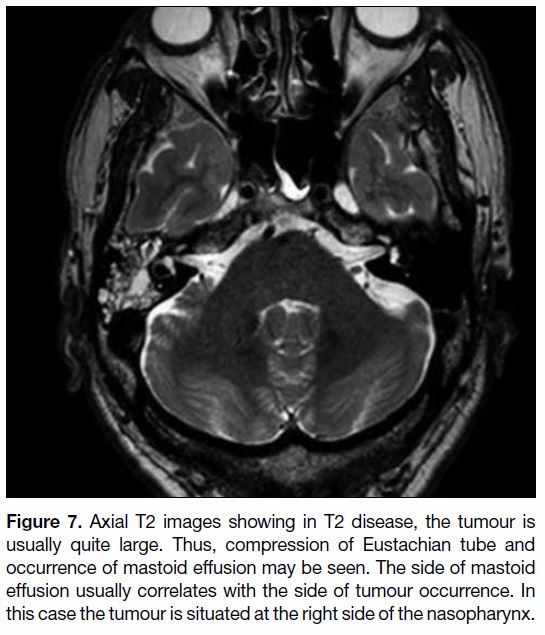

With T2 disease, the tumour is usually quite sizable and often compresses the Eustachian tube with consequent

complications such as mastoid effusion (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Axial T2 images showing in T2 disease, the tumour is

usually quite large. Thus, compression of Eustachian tube and

occurrence of mastoid effusion may be seen. The side of mastoid

effusion usually correlates with the side of tumour occurrence. In

this case the tumour is situated at the right side of the nasopharynx.

Adjacent soft tissue involvement including the medial

pterygoid, lateral pterygoid or prevertebral muscles

have been added to T2 classification in addition to

parapharyngeal involvement in the AJCC 8th edition.

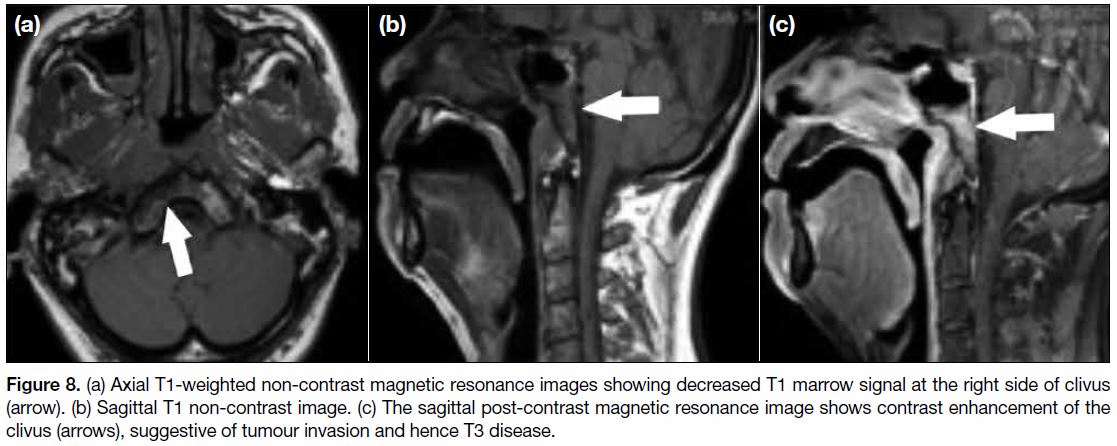

T3 Disease

T3 disease is defined as tumour with infiltration of bony

structures at the skull base, cervical vertebra, pterygoid

structures, and/or paranasal sinuses.[9] The most common

bony structures involved include the clivus (Figure 8), the pterygoid bones, petrous apices and body of

sphenoid. Bony invasion can be readily confirmed

through evaluation of any loss of T1 fatty marrow signal

and comparison of bilateral bony structures.[9]

Figure 8. (a) Axial T1-weighted non-contrast magnetic resonance images showing decreased T1 marrow signal at the right side of clivus

(arrow). (b) Sagittal T1 non-contrast image. (c) The sagittal post-contrast magnetic resonance image shows contrast enhancement of the

clivus (arrows), suggestive of tumour invasion and hence T3 disease.

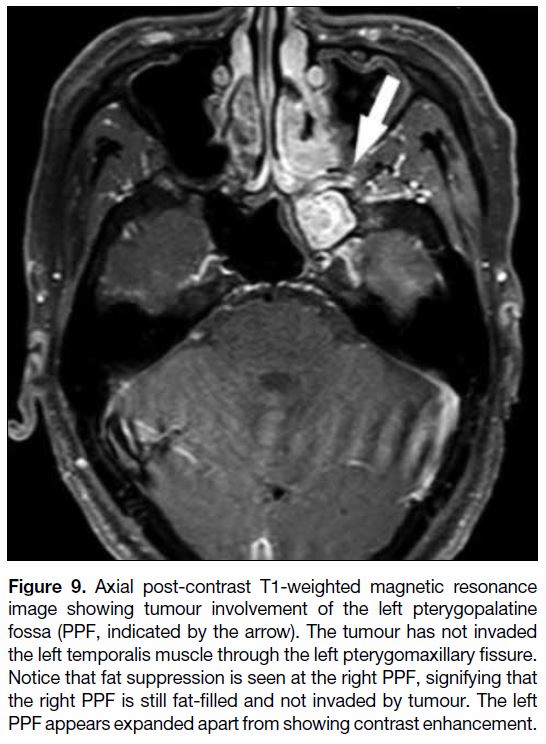

A couple of skull base foramina and canal are also

evaluated, including the foramen lacerum, foramen ovale,

foramen spinosum, foramen rotundum, carotid canal,

jugular foramen, and hypoglossal canal. As most of these

skull base foramina enable passage of neurovascular

structures craniocaudally, optimal evaluation uses the

coronal plane that has the added benefit of enabling

bilateral structural comparison. Involvement of the

pterygopalatine fossa is commonly denoted as T3 and

evaluation of this structure is of utmost importance in

staging nasopharyngeal carcinoma as this structure

is cross-roads in head and neck imaging (Figure 9).

Medially it communicates with the nasal cavity via the

sphenopalatine foramen. Laterally it communicates with

the masticator space via the pterygomaxillary fissure.

Figure 9. Axial post-contrast T1-weighted magnetic resonance

image showing tumour involvement of the left pterygopalatine

fossa (PPF, indicated by the arrow). The tumour has not invaded

the left temporalis muscle through the left pterygomaxillary fissure.

Notice that fat suppression is seen at the right PPF, signifying that

the right PPF is still fat-filled and not invaded by tumour. The left

PPF appears expanded apart from showing contrast enhancement.

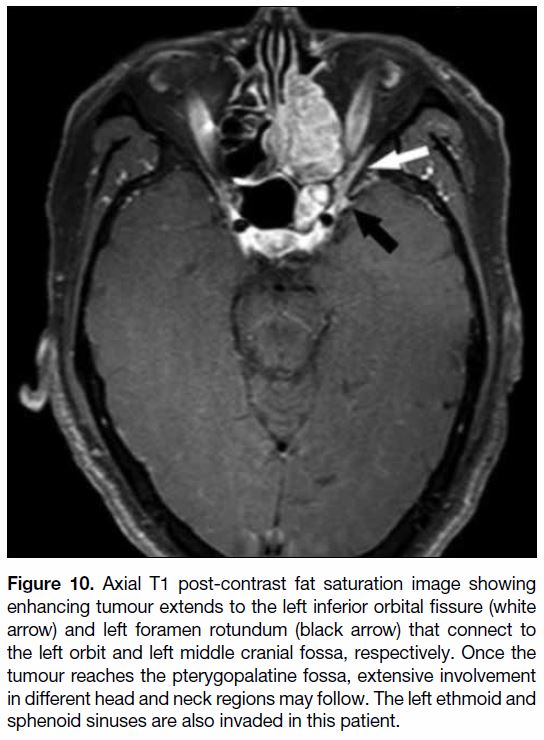

Anteriorly it continues into the orbit through the inferior

orbital fissure (Figure 10). Posteriorly and superiorly, it

communicates with the cavernous sinuses of the middle

cranial fossa through the foramen rotundum (Figure 10).

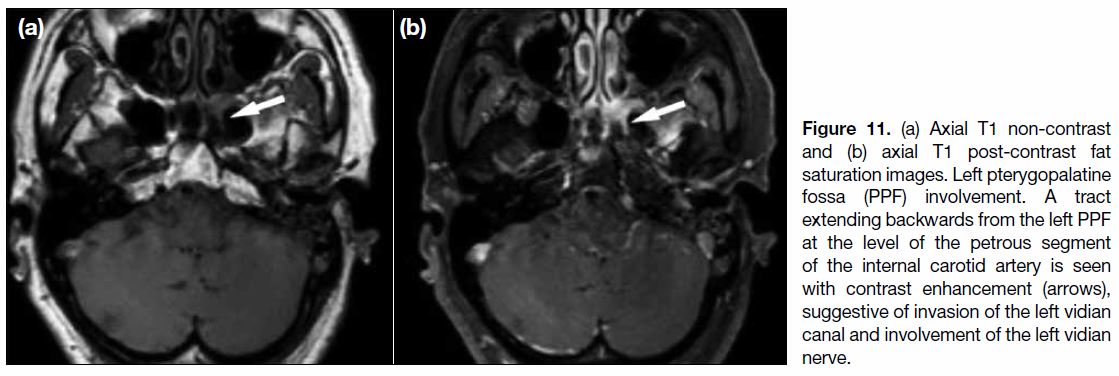

Posteriorly and inferiorly, another passage into the middle

cranial fossa is through the vidian canal (Figure 11).

Posteriorly and medially, it communicates with the

nasal cavity via the palatovaginal canal. Inferiorly,

it continues into the palate via the greater and lesser

palatine canals.

Figure 10. Axial T1 post-contrast fat saturation image showing

enhancing tumour extends to the left inferior orbital fissure (white

arrow) and left foramen rotundum (black arrow) that connect to

the left orbit and left middle cranial fossa, respectively. Once the

tumour reaches the pterygopalatine fossa, extensive involvement

in different head and neck regions may follow. The left ethmoid and

sphenoid sinuses are also invaded in this patient.

Figure 11. (a) Axial T1 non-contrast and (b) axial T1 post-contrast fat saturation images. Left pterygopalatine fossa (PPF) involvement. A tract extending backwards from the left PPF at the level of the petrous segment of the internal carotid artery is seen with contrast enhancement (arrows), suggestive of invasion of the left vidian canal and involvement of the left vidian nerve.

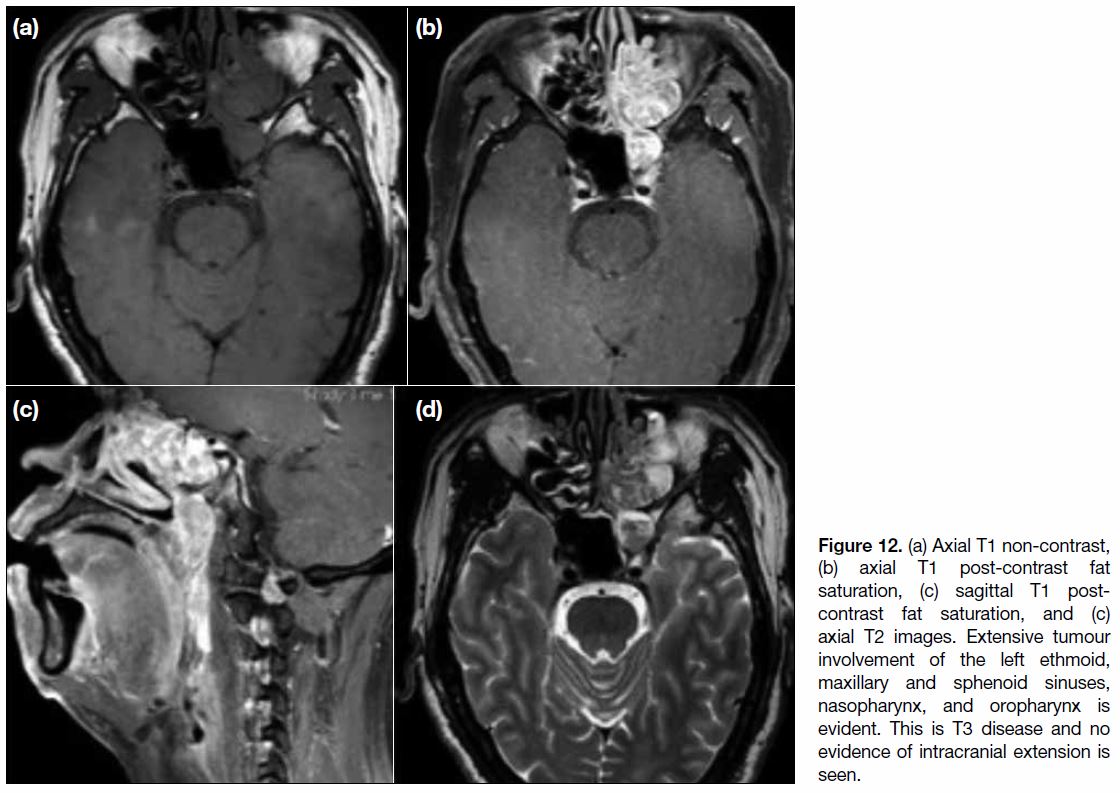

When the tumour invades the paranasal sinuses, the

disease is quite advanced (Figure 12). Continuity

between a mass at the nasopharynx and paranasal sinus

disease involvement is often observed. Absence of

metastasis to the paranasal sinuses is rare.[9] [12] When a

solitary paranasal sinus tumour is seen, another primary

with differential diagnoses including sinonasal squamous

cell carcinoma or sinonasal undifferentiated carcinoma

should be considered.[16]

Figure 12. (a) Axial T1 non-contrast, (b) axial T1 post-contrast fat saturation, (c) sagittal T1 post-contrast fat saturation, and (c) axial T2 images. Extensive tumour involvement of the left ethmoid, maxillary and sphenoid sinuses, nasopharynx, and oropharynx is evident. This is T3 disease and no evidence of intracranial extension is seen.

In T3 disease, further specification of bony structure

involvement including the skull base, cervical vertebra

and pterygoid structures has been added to the AJCC 8th

edition.

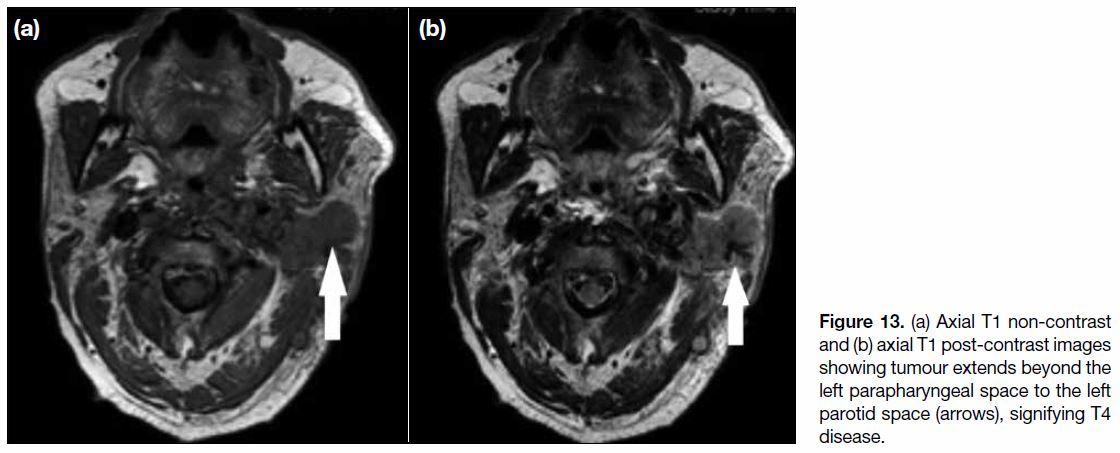

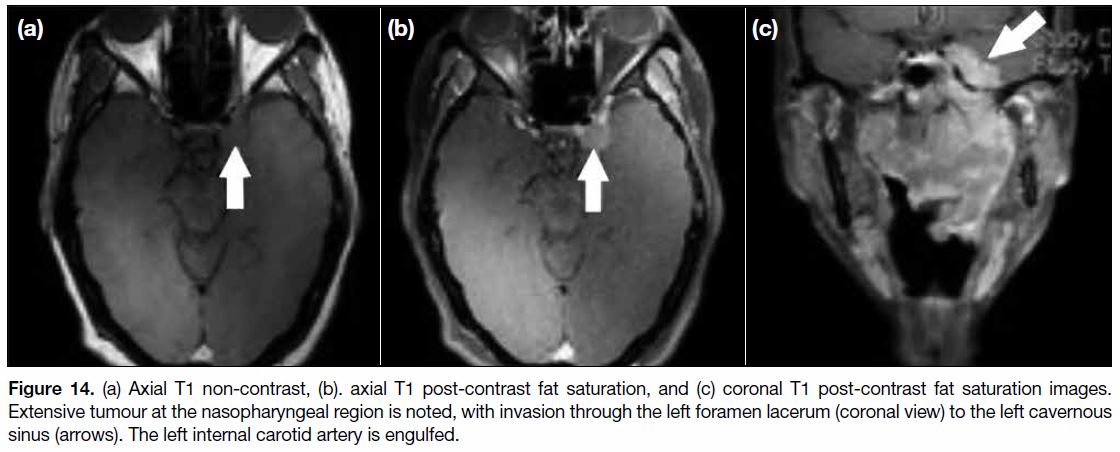

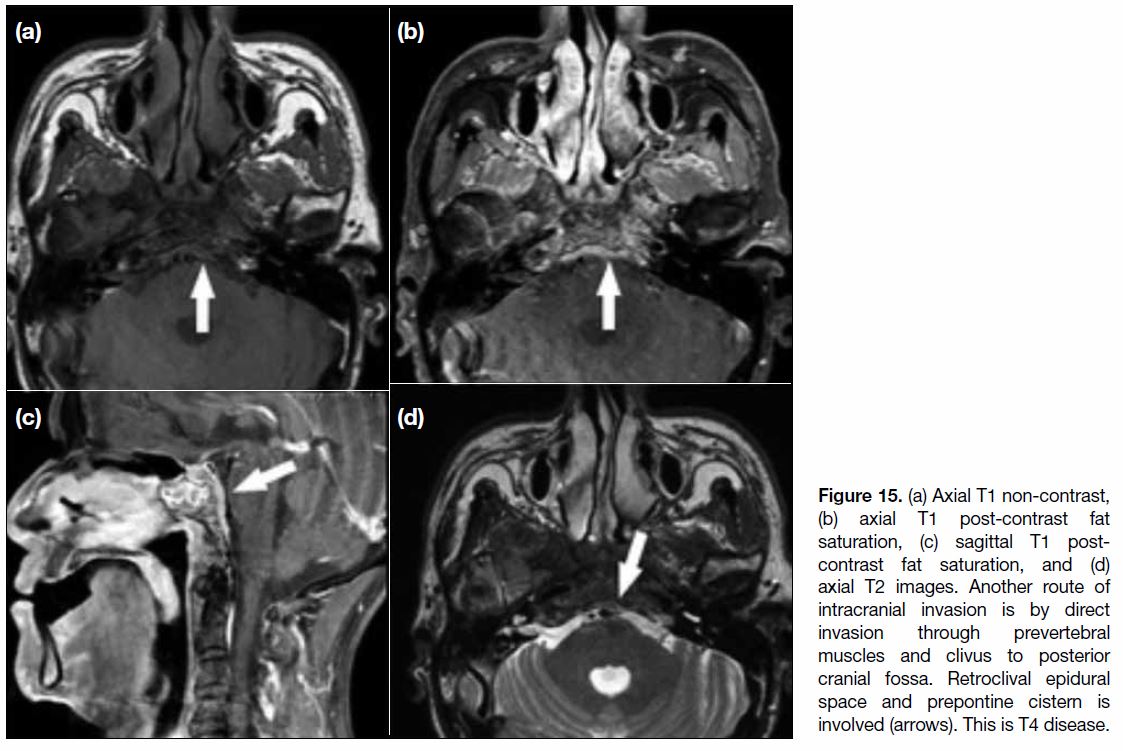

T4 Disease

T4 disease includes tumour with intracranial extension,

involvement of cranial nerves, hypopharynx, orbit,

parotid gland (Figure 13), and/or extensive soft tissue

infiltration beyond the lateral surface of the lateral

pterygoid muscle.[9] Involvement of the hypopharynx

is rare and associated with a much poorer outcome.

The disease is thus upgraded from T1 to T4 when

the tumour extends through the oropharynx to the

hypopharynx. When the cavernous sinus is invaded

(Figure 14), symptoms include those affected by cranial

nerve III, IV, V1, V2 and VI function. It is usually the

site of involvement when disease spread is from the

pterygopalatine fossa through the foramen rotundum

before further disease involvement of the cerebrum.

In involvement of the posterior cranial fossa, the most

common route of invasion is through the longus colli

muscle and clivus, with extension to the prepontine cistern (Figure 15).[12] In severe cases, invasion of tumour from

the pterygopalatine fossa into the orbit through the

inferior orbital fissure can be seen.[14] Proptosis may be

noted due to mass effect of the tumour.

Figure 13. (a) Axial T1 non-contrast and (b) axial T1 post-contrast images showing tumour extends beyond the left parapharyngeal space to the left parotid space (arrows), signifying T4 disease.

NX or

Figure 14. (a) Axial T1 non-contrast, (b). axial T1 post-contrast fat saturation, and (c) coronal T1 post-contrast fat saturation images.

Extensive tumour at the nasopharyngeal region is noted, with invasion through the left foramen lacerum (coronal view) to the left cavernous

sinus (arrows). The left internal carotid artery is engulfed.

Figure 15. (a) Axial T1 non-contrast, (b) axial T1 post-contrast fat saturation, (c) sagittal T1 post-contrast fat saturation, and (d) axial T2 images. Another route of intracranial invasion is by direct invasion through prevertebral muscles and clivus to posterior cranial fossa. Retroclival epidural space and prepontine cistern is involved (arrows). This is T4 disease.

In T4 disease, “extension to parotid gland and/or extensive

soft tissue infiltration beyond the lateral surface of lateral

pterygoid muscle” in the AJCC 8th edition replaces “extension to infratemporal fossa/masticator space” in

the AJCC 7th edition. Other contents such as intracranial

extension, involvement of cranial nerves, hypopharynx,

and/or orbit are unchanged.

N STAGE

Detailed descriptions of staging of regional lymph nodes

can be found in the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual.[9]

NX or N0

NX signifies that regional lymph nodes cannot be

assessed while N0 indicates that no regional lymph node

metastasis is noted.

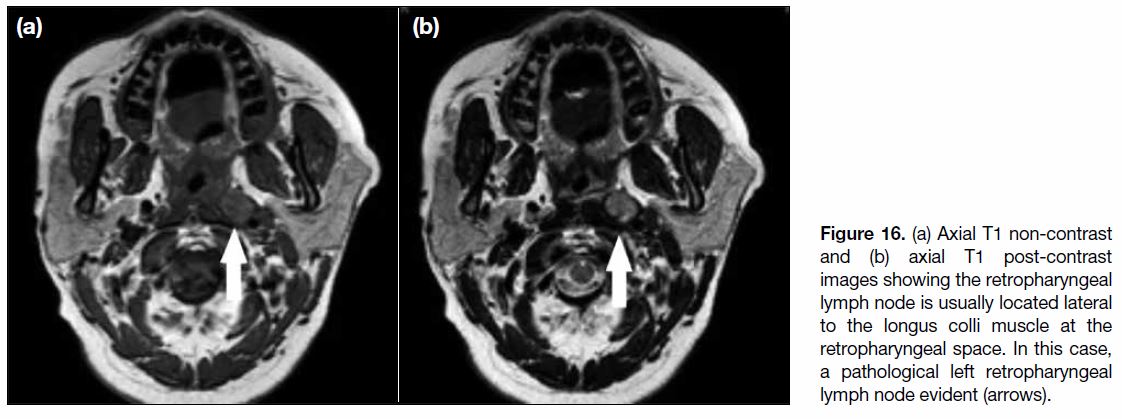

N1 Disease

N1 denotes unilateral metastasis in cervical lymph nodes

and/or unilateral or bilateral metastasis in retropharyngeal

lymph nodes, ≤6 cm at their largest dimension, above the caudal border of the cricoid cartilage.[9] In addition

to T2 and T1 post-contrast images for primary tumour

and nodal metastasis, diffusion-weighted imaging is also

valuable for assessment of nodal metastasis.[17] The most

important lymph node to evaluate is the retropharyngeal

lymph node, a node located at the retropharyngeal space usually lateral to prevertebral muscle (Figure 16). It is

the most common and earliest node to be involved in

nasopharyngeal carcinoma. The lymphatic involvement

of cervical lymph nodes usually follows a specific pattern

with first involvement of the retropharyngeal lymph

nodes, then spreading from upper to lower cervical nodes.[18] Skip metastases are not common but can still

happen with cases that show involvement of cervical

nodes without involvement of the retropharyngeal lymph

node.[9] [18]

Figure 16. (a) Axial T1 non-contrast and (b) axial T1 post-contrast images showing the retropharyngeal lymph node is usually located lateral to the longus colli muscle at the retropharyngeal space. In this case, a pathological left retropharyngeal lymph node evident (arrows).

For N1 disease, “above the caudal border of cricoid

cartilage” has replaced “above supraclavicular fossa” in

the AJCC 8th edition.

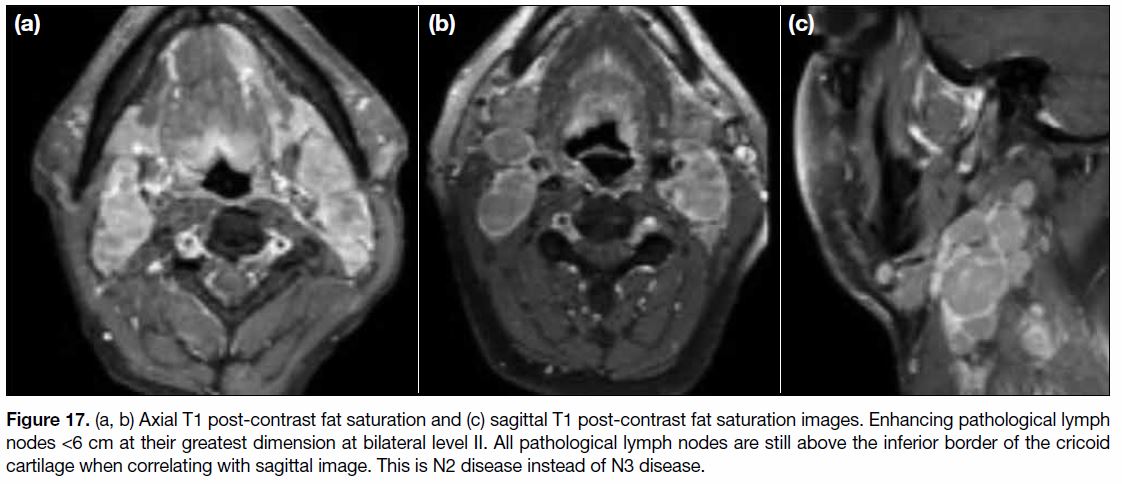

N2 Disease

N2 disease is diagnosed when there are bilateral

metastases in cervical lymph nodes, ≤6 cm at the largest

dimension and above the caudal border of cricoid

cartilage (Figure 17).[9] It denotes bilateral lymph node

involvement at level IIa, IIb, III and Va. Level IIa and IIb lymph nodes are the most commonly involved nonretropharyngeal

lymph nodes. Lymph nodes from level

IIa are the higher internal jugular group, above the

hyoid bone and in contact with the internal jugular vein.

Level IIb lymph nodes are also above the hyoid bone

but posterior to and separated from the internal jugular

vein although still anterior to the posterior border of the

sternocleidomastoid (SCM) muscle. Level III nodes are

between the level of the inferior border of the hyoid bone

and the inferior border of the cricoid cartilage and beneath

the SCM muscle. Level Va are any nodes posterior to

the posterior border of the SCM muscle and above the

inferior border of the cricoid cartilage. Involvement of

submental (level Ia) and submandibular (level Ib) lymph

nodes is uncommon but should be excluded.

Figure 17. (a, b) Axial T1 post-contrast fat saturation and (c) sagittal T1 post-contrast fat saturation images. Enhancing pathological lymph

nodes <6 cm at their greatest dimension at bilateral level II. All pathological lymph nodes are still above the inferior border of the cricoid

cartilage when correlating with sagittal image. This is N2 disease instead of N3 disease.

For N2 disease, “above the caudal border of cricoid

cartilage” has replaced “above supraclavicular fossa” in

the AJCC 8th edition.

N3 Disease

N3 disease is said to be present when any cervical lymph

nodes exceed 6 cm at their largest dimension and/or with

extension below the caudal border of the cricoid cartilage,

regardless of laterality of lymph node involvement.[9] It

refers to any pathological lymph nodes at level IV or Vb.

Involvement of these nodes carries the worst prognosis

as they are the most distant cervical lymph nodes to be

involved.[9]

For N3 disease, “below the caudal border of cricoid

cartilage” has replaced “in supraclavicular fossa” in the

AJCC 8th edition.

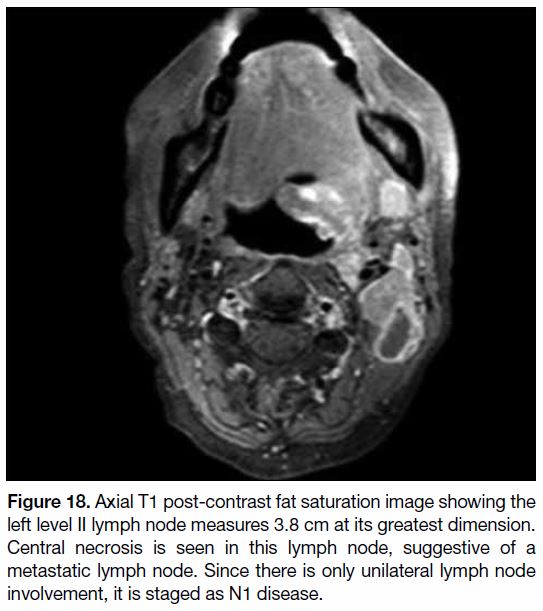

For AJCC criteria, the nodal staging is based on maximum

dimension, laterality, and site of lymph nodes. Any

lymph nodes along the midline are considered ipsilateral

nodes. Nonetheless identification of nodal metastases

relies on a short axis of lymph nodes and morphological

features including central necrosis and extranodal

extension (Figure 18).[19] In general, most cervical lymph

nodes normally should be <10 mm in their short axis. In

particular, normal retropharyngeal lymph nodes should

not exceed 5 mm in the short axis.[20] If positron emission

tomography–computed tomography is performed, any marked hypermetabolism of lymph nodes along the

expected nodal path of disease spread should raise a

suspicion of lymph node metastases, regardless of size

of lymph nodes.[21] One more point to note is that the size

of the primary tumour does not correlate with the extent

of nodal metastases.[12]

Figure 18. Axial T1 post-contrast fat saturation image showing the

left level II lymph node measures 3.8 cm at its greatest dimension.

Central necrosis is seen in this lymph node, suggestive of a

metastatic lymph node. Since there is only unilateral lymph node

involvement, it is staged as N1 disease.

CONCLUSION

Nasopharyngeal carcinoma staging is important to guide

treatment and determine disease prognosis. Head and

neck magnetic resonance imaging adds high value in

achieving this goal. Its multiplanar capability, high soft

tissue contrast, and immense anatomical detail makes

it a powerful imaging modality. The staging method in

this article is based on AJCC 8th edition. Major changes

from the AJCC 7th edition include incorporation of

involvement of medial pterygoid, lateral pterygoid

or prevertebral muscles into T2 disease, further

specification of bony structure involvement including

skull base, cervical vertebra and pterygoid structures in

T3 disease, and discarding of terms such as infratemporal

fossa/masticator space in T4 disease and replacement

with “soft tissue infiltration beyond the lateral surface of

lateral pterygoid muscle”. Nodal staging is now classified

using the anatomical boundary of the caudal border of

the cricoid cartilage instead of supraclavicular fossa.

Continuous update on disease staging will be necessary

in the future with advancement of imaging modality and

treatment options.

REFERENCES

1. Som PM, Curtin HD, editors. Head and Neck Imaging. St. Louis (MO): Mosby-Year Book; 2003.

2. King AD, Vlantis AC, Tsang RK, Gary TM, Au AK, Chan CY, et al.

Magnetic resonance imaging for the detection of nasopharyngeal

carcinoma. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2006;27:1288-91.

3. Cao SM, Simons MJ, Qian CN. The prevalence and prevention of

nasopharyngeal carcinoma in China. Chin J Cancer. 2011;30:114-9. Crossref

4. Xie SH, Yu IT, Tse LA, Mang OW, Yue L. Sex difference in the

incidence of nasopharyngeal carcinoma in Hong Kong 1983-2008:

Suggestion of a potential protective role of oestrogen. Eur J Cancer.

2013;49:150-5. Crossref

5. Tsao SW, Yip YL, Tsang CM, Pang PS, Lau VM, Zhang G, et al.

Etiological factors of nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Oral Oncol.

2014;50:330-8. Crossref

6. Stenmark MH, McHugh JB, Schipper M, Walline HM, Komarck C,

Feng FY, et al. Nonendemic HPV-positive nasopharyngeal

carcinoma: association with poor prognosis. Int J Radiat Oncol

Biol Phys. 2014;88:580-8. Crossref

7. Yu KJ, Gao X, Chen CJ, Yang XR, Diehl SR, Goldstein A, et al.

Association of human leukocyte antigens with nasopharyngeal

carcinoma in high-risk multiplex families in Taiwan. Hum

Immunol. 2009;70:910-4. Crossref

8. Thompson LD. Update on nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Head Neck

Pathol. 2007;1:81-6. Crossref

9. Lee AW, Lydiatt WM, Colevas AD, Glastonbury CM, Le QT, O’Sullivan B, et al. Nasopharynx. In: Amin MB, editor. AJCC

Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. American College of Surgeons;

2018: p 103-11. Crossref

10. Lau KY, Kan WK, Sze WM, Lee AW, Chan JK, Yau TK, et al.

Magnetic resonance for T-staging of nasopharyngeal carcinoma —

the most informative pair of sequences. Jpn J Clin Oncol.

2004;34:171-5. Crossref

11. Lydiatt WM, Patel SG, O’Sullivan B, Brandwein MS, Ridge JA,

Migliacci JC, et al. Head and Neck cancers — major changes in the

American Joint Committee on cancer eighth edition cancer staging

manual. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67:122-37. Crossref

12. King AD, Bhatia KS. Magnetic resonance imaging staging of

nasopharyngeal carcinoma in the head and neck. World J Radiol.

2010;2:159-65. Crossref

13. Carle LN, Ko CC, Castle JT. Nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Head Neck Pathol. 2012;6:364-8. Crossref

14. King AD, Lam WW, Leung SF, Chan YL, Teo P, Metreweli C.

MRI of local disease in nasopharyngeal carcinoma: tumour extent

vs tumour stage. Br J Radiol. 1999;72:734-41. Crossref

15. Harnsberger HR, Osborn AG. Differential diagnosis of head and

neck lesions based on their space of origin. 1. The suprahyoid part

of the neck. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1991;157:147-54. Crossref

16. Wenig BM, Richardson M. Nasal cavity, paranasal sinuses, and

nasopharynx. In: Weidner N, Cote R, Suster S, Weiss L, editors.

Modern Surgical Pathology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2009:

p 141-207. Crossref

17. Li H, Liu XW, Geng ZJ, Wang DL, Xie CM. Diffusion-weighted

imaging to differentiate metastatic from non-metastatic

retropharyngeal lymph nodes in nasopharyngeal carcinoma.

Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2015;44:20140126. Crossref

18. Ho FC, Tham IW, Earnest A, Lee KM, Lu JJ. Patterns of regional

lymph node metastasis of nasopharyngeal carcinoma: a meta-analysis

of clinical evidence. BMC Cancer. 2012;12:98. Crossref

19. Lu L, Wei X, Li YH, Li WB. Sentinel node necrosis is a negative

prognostic factor in patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma: a

magnetic resonance imaging study of 252 patients. Curr Oncol.

2017;24:e220-5. Crossref

20. Zhang GY, Liu LZ, Wei WH, Deng YM, Li YZ, Liu XW.

Radiologic criteria of retropharyngeal lymph node metastasis

in nasopharyngeal carcinoma treated with radiation therapy.

Radiology. 2010;255:605-12. Crossref

21. Lin XP, Zhao C, Chen MY, Fan W, Zhang X, Zhi SF, et al. Role

of 18F-FDG PET/CT in diagnosis and staging of nasopharyngeal

carcinoma [in Chinese]. Ai Zheng. 2008;27:974-8.