Post-irradiation Changes and Complications of Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma: A Review of Imaging Features

PICTORIAL ESSAY

Post-irradiation Changes and Complications of Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma: A Review of Imaging Features

JCY Lau, JHM Cheng, SY Luk, JLS Khoo

Department of Radiology, Pamela Youde Nethersole Eastern Hospital, Chai Wan, Hong Kong

Correspondence: Dr JCY Lau, Department of Radiology, Pamela Youde Nethersole Eastern Hospital, Chai Wan, Hong Kong. Email: jackylcy135@yahoo.com.hk

Submitted: 26 Mar 2019; Accepted: 3 Jun 2019.

Contributors: JHMC, SYL and JLSK designed the study; JCYL and JHMC acquired and analysed the data; JCYL drafted the manuscript;

JHMC, SYL and JLSK critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors had full access to the data, contributed to

the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Funding/Support: This pictorial essay received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics Approval: This study was approved by the Hospital Authority Hong Kong East Cluster Research Ethics Committee (Ref

HKECREC-2019-037).

INTRODUCTION

Nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) is a relatively

common malignancy in Hong Kong. Radiotherapy

(RT) plays a major role in the treatment of early and

intermediate stage disease. Despite advancement from

conventional two-dimensional RT to three-dimensional

or intensity-modulated RT, post-irradiation changes and

complications are still commonly encountered. These

changes may evolve over time and may manifest early

or years after completion of RT. Differentiating these

expected post-irradiation changes from residual tumour

and disease recurrence can be challenging.

This article aims to review the imaging features of

common post-irradiation changes at different stages of

treatment and a broad spectrum of irradiation-related

complications in patients with NPC.

COMMON POST-IRRADIATION CHANGES

Mucocutaneous Changes

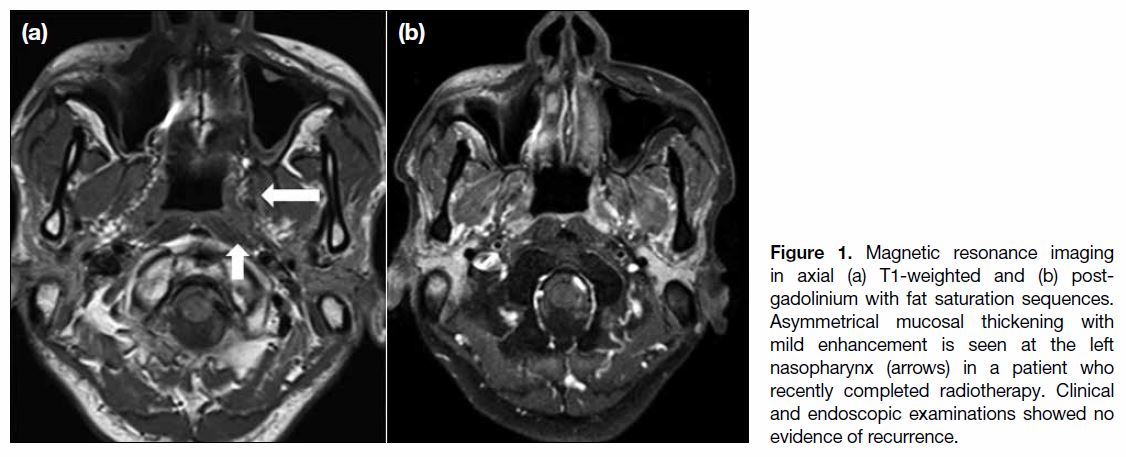

Mucocutaneous tissue is commonly affected by radiation

due to its high radiosensitivity, causing mucositis.

Inflammation can be due to direct irradiation and/or

increased epithelial susceptibility to infection. Diagnosis

is based mainly on clinical findings, although pharyngeal mucosal hyperenhancement and thickening can be

encountered radiologically at the early stage (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Magnetic resonance imaging in axial (a) T1-weighted and (b) post-gadolinium with fat saturation sequences. Asymmetrical mucosal thickening with mild enhancement is seen at the left nasopharynx (arrows) in a patient who recently completed radiotherapy. Clinical and endoscopic examinations showed no evidence of recurrence.

Chronic mucositis can appear as mucosal atrophy,

necrosis and/or ulcerative changes, posing difficulty in

distinguishing them from malignant changes.[1] Other chronic changes including choanal atresia, paranasal sinus mucocele, and polyp formation have also been

reported.[2]

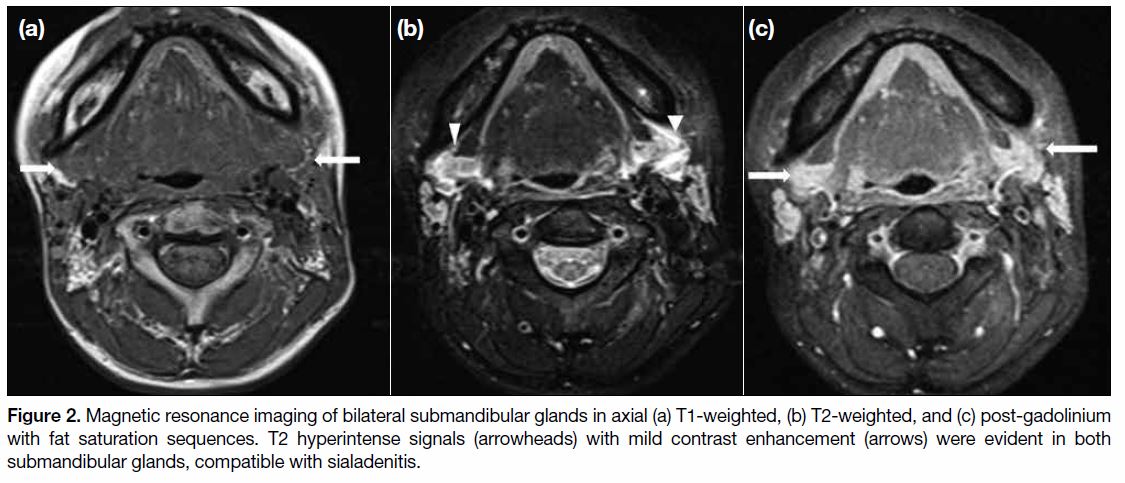

Glandular Changes

One of the most common potentially highly disabling

side-effects of RT in the head and neck region is

xerostomia.[2] The salivary glands are frequently affected

by radiation, transiently or permanently. Glandular tissue

may appear oedematous (Figure 2) with heterogeneous

signal and enhancement on magnetic resonance imaging

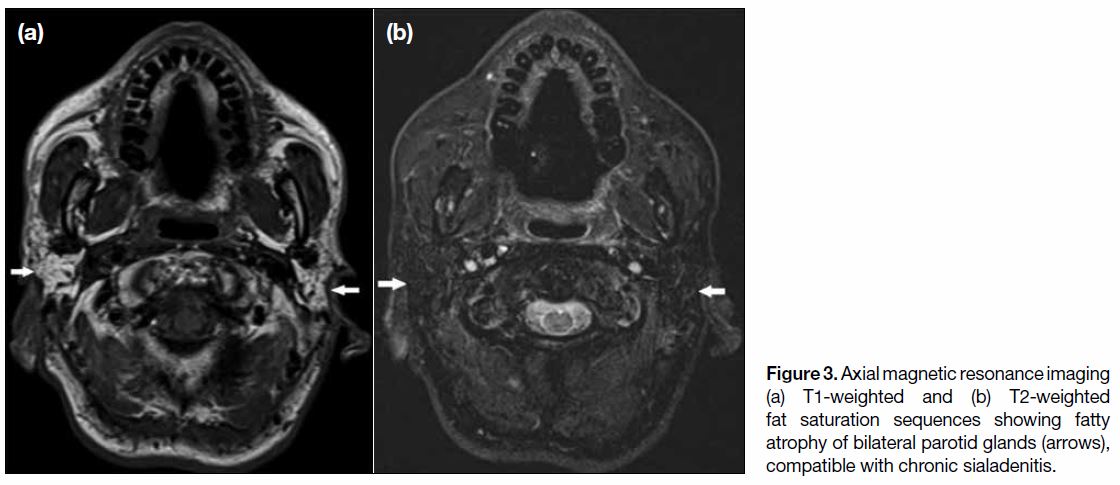

(MRI) at the early treatment stage. Atrophy and/or

fatty infiltration may be encountered at a later stage of

treatment (Figure 3).[3]

Figure 2. Magnetic resonance imaging of bilateral submandibular glands in axial (a) T1-weighted, (b) T2-weighted, and (c) post-gadolinium

with fat saturation sequences. T2 hyperintense signals (arrowheads) with mild contrast enhancement (arrows) were evident in both

submandibular glands, compatible with sialadenitis.

Figure 3. Axial magnetic resonance imaging

(a) T1-weighted and (b) T2-weighted

fat saturation sequences showing fatty

atrophy of bilateral parotid glands (arrows),

compatible with chronic sialadenitis.

The pituitary gland may also be damaged by irradiation,

impairing the hypothalamic-pituitary hormonal axis with

consequent hormonal deficiencies. Nonetheless MRI

findings are usually unremarkable despite the presence

of symptomatic neuroendocrine deficiency.[2]

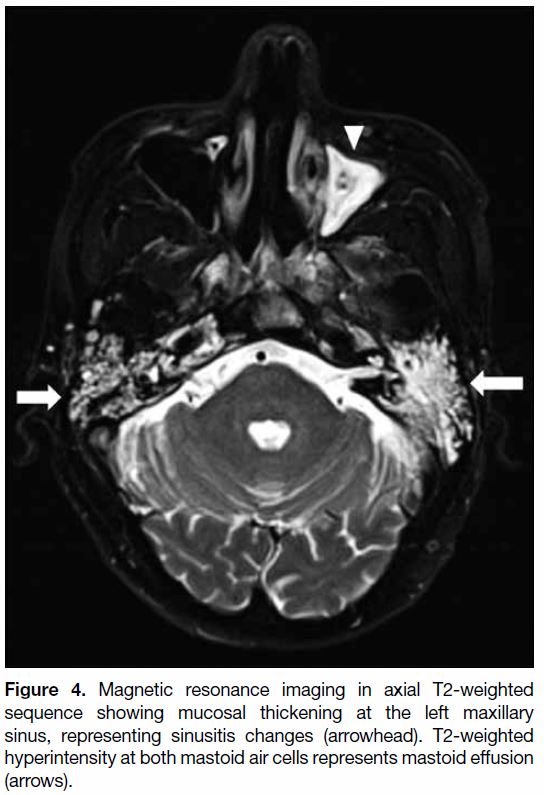

Sinusitis and Otomastoiditis

Post-irradiation and at the early stage of treatment,

patients commonly experience a certain degree of

sinusitis and/or otomastoiditis (Figure 4), mainly due to

reactive oedema of the mucosa and blockage of meatal

openings. The incidence of mastoiditis usually increases

during the first few months of treatment. Imaging features

include T2-weighted (TW2) hyperintense effusion, with

or without contrast enhancement and restricted diffusion.

In severe cases, subperiosteal abscess may develop.[4]

Figure 4. Magnetic resonance imaging in axial T2-weighted

sequence showing mucosal thickening at the left maxillary

sinus, representing sinusitis changes (arrowhead). T2-weighted

hyperintensity at both mastoid air cells represents mastoid effusion

(arrows).

Over time, chronic sinusitis and/or otomastoiditis are

observed in some irradiated patients, although the

incidence is lower than during early treatment.[4] The

acute inflammation may become crusted with adhesions

months to years after completion of RT.

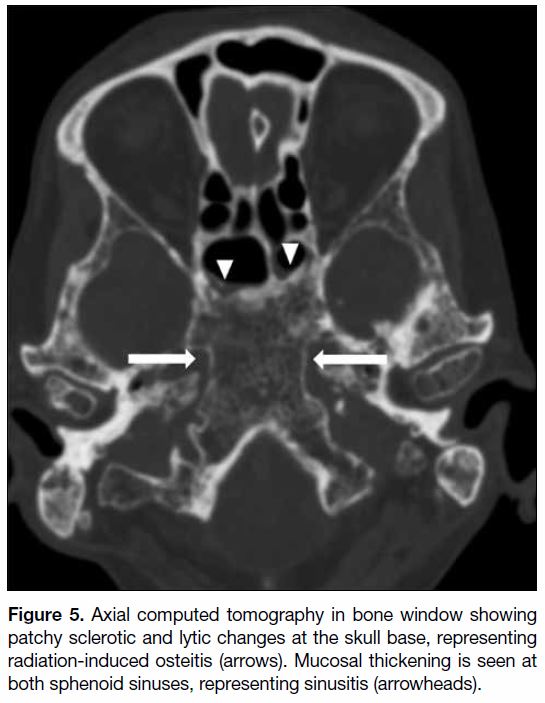

Radiation-induced osteitis

Radiation-induced osteitis is commonly asymptomatic

and involves the sphenoid bone at the skull base and upper

cervical spine. Radiation-induced fatty replacement of marrow is the most common osseous imaging

abnormality in post-irradiation patients, although initial

imaging may be normal. On computed tomography,

a mottled appearance of the skull base with mixed

patchy sclerosis and lucency and coarsened trabeculum

can be observed (Figure 5).[1] Further progression to

osteoradionecrosis with osseous changes can be seen in

some cases and will be further discussed later on.

Figure 5. Axial computed tomography in bone window showing

patchy sclerotic and lytic changes at the skull base, representing

radiation-induced osteitis (arrows). Mucosal thickening is seen at

both sphenoid sinuses, representing sinusitis (arrowheads).

Others

Other common changes including trismus, skin and neck

fibrosis are beyond the scope of this review.

POST-RADIATION COMPLICATIONS

Radiation Injury to the Nervous System

Temporal Lobe Necrosis

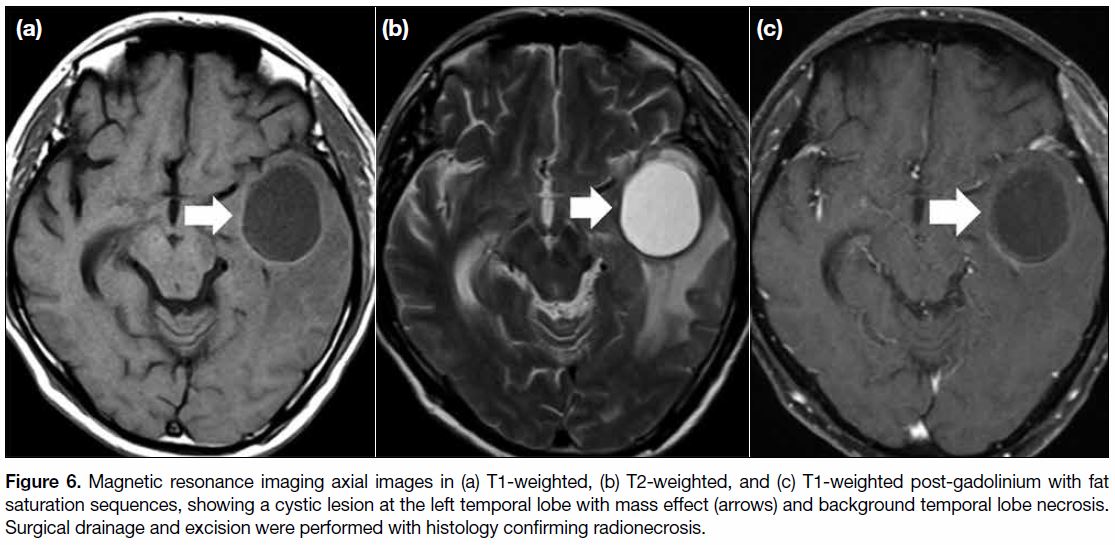

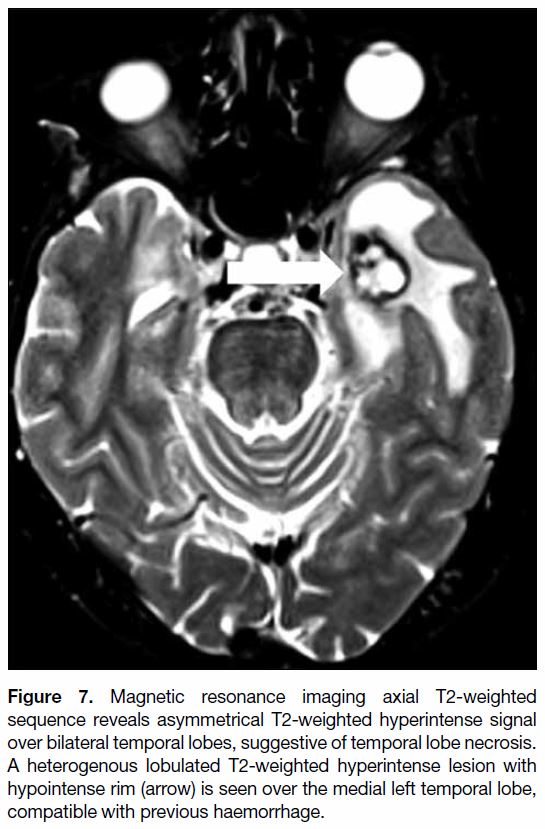

One of the most debilitating and serious neurological

complications is temporal lobe necrosis (TLN). It has a

latent period of 1.5 to 13 years.[5] The inferomedial aspects

of the temporal lobes are most commonly involved due

to their close proximity to the radiation field at the skull

base, with bilateral involvement in up to approximately

two-thirds of patients.[6] Histological examination shows

oedema, reactive gliosis and demyelination, followed by cavitation and necrosis. Imaging findings include focal or

extensive homogenous T2W hyperintensity in the white

matter, representing white matter rarefaction of myelin

or oedema. Associated mass effect may be present,

especially when there is extensive white matter injury.

Grey matter lesions occur in up to 90% of patients but

are usually less extensive,[7] with the inferior aspects of the

temporal lobes being most susceptible since they receive

a higher radiation dosage. MRI shows necrotic foci and

contrast enhancing lesions that may progress or resolve

over time.[2] In some cases, TLN may be complicated by

cystic formation (Figure 6) or haemorrhage at later stages

(Figure 7).[8] Steroid is thought to be useful to reduce the oedema of TLN.[7]

Figure 6. Magnetic resonance imaging axial images in (a) T1-weighted, (b) T2-weighted, and (c) T1-weighted post-gadolinium with fat

saturation sequences, showing a cystic lesion at the left temporal lobe with mass effect (arrows) and background temporal lobe necrosis.

Surgical drainage and excision were performed with histology confirming radionecrosis.

Figure 7. Magnetic resonance imaging axial T2-weighted

sequence reveals asymmetrical T2-weighted hyperintense signal

over bilateral temporal lobes, suggestive of temporal lobe necrosis.

A heterogenous lobulated T2-weighted hyperintense lesion with

hypointense rim (arrow) is seen over the medial left temporal lobe,

compatible with previous haemorrhage.

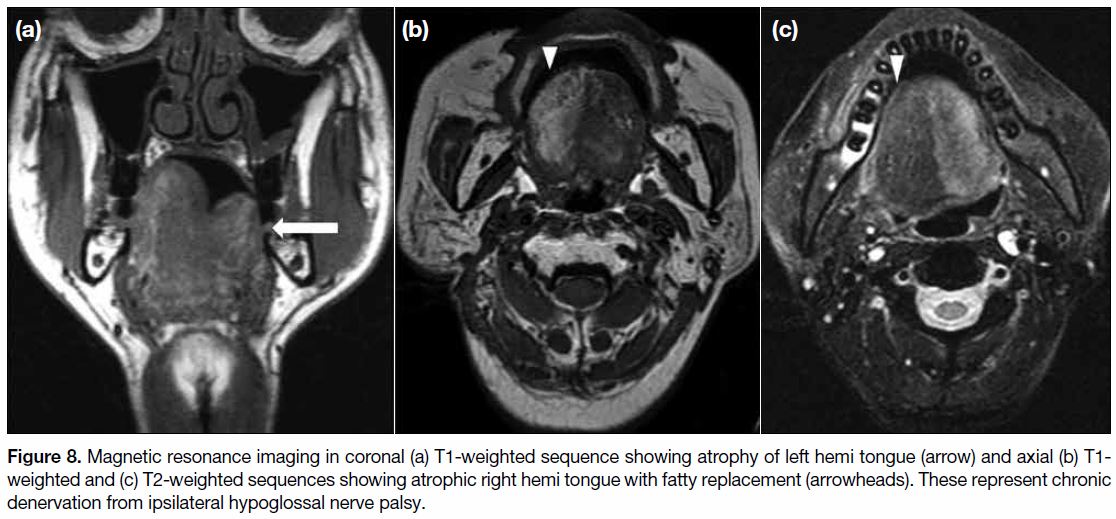

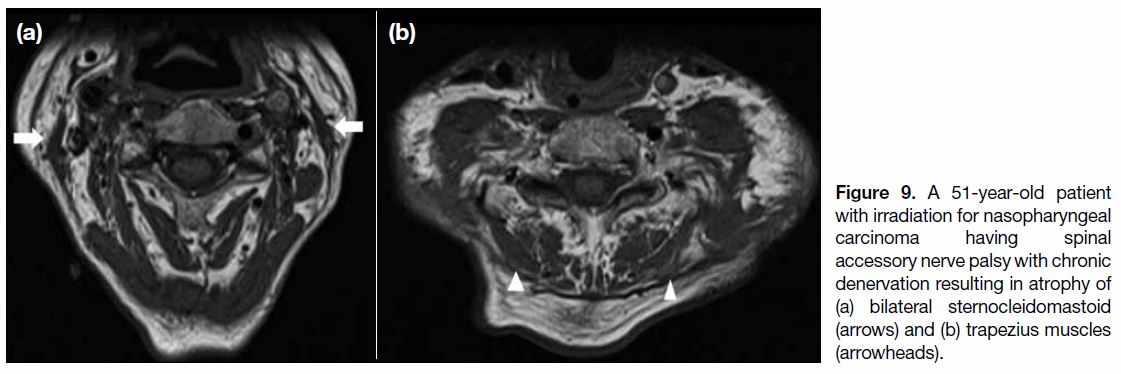

Cranial Nerve Palsy

The second most common site of neurological injury

is the cranial nerves, especially the hypoglossal nerve,

followed by the vagus nerve and recurrent laryngeal

nerve.[9] MRI may demonstrate secondary signs of cranial

nerve palsy that include oedema, fatty infiltration and

atrophy of the respective muscles supplied by the affected

cranial nerve, namely the ipsilateral hemitongue in

hypoglossal nerve palsy (Figure 8), sternocleidomastoid

and trapezius muscles in spinal accessory nerve palsy

(Figure 9).

Figure 8. Magnetic resonance imaging in coronal (a) T1-weighted sequence showing atrophy of left hemi tongue (arrow) and axial (b) T1-weighted and (c) T2-weighted sequences showing atrophic right hemi tongue with fatty replacement (arrowheads). These represent chronic

denervation from ipsilateral hypoglossal nerve palsy.

Figure 9. A 51-year-old patient

with irradiation for nasopharyngeal carcinoma having spinal accessory nerve palsy with chronic denervation resulting in atrophy of (a) bilateral sternocleidomastoid (arrows) and (b) trapezius muscles (arrowheads).

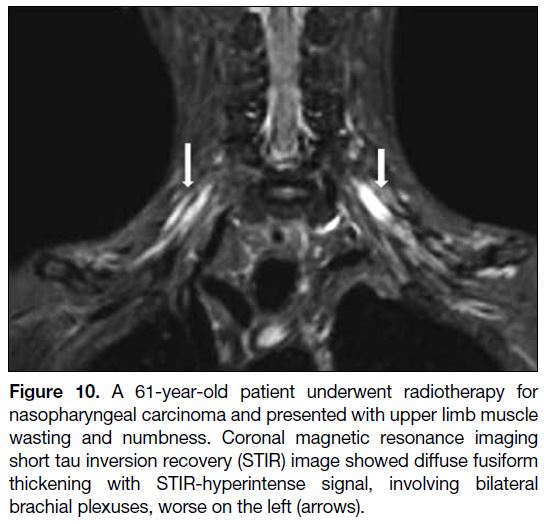

Brachial Plexopathy

Although injury to the nervous system at the lower neck

is less commonly seen nowadays, brachial plexopathy

may be encountered occasionally. On MRI, the brachial

plexus may appear thickened with T2W hyperintensity

and contrast enhancement (Figure 10).[10] Atrophy of the

serratus anterior, rotator cuff muscles can be seen in

chronic denervation. It has a peak incidence 10 to 20

months post-radiation.

Figure 10. A 61-year-old patient underwent radiotherapy for

nasopharyngeal carcinoma and presented with upper limb muscle

wasting and numbness. Coronal magnetic resonance imaging

short tau inversion recovery (STIR) image showed diffuse fusiform

thickening with STIR-hyperintense signal, involving bilateral

brachial plexuses, worse on the left (arrows).

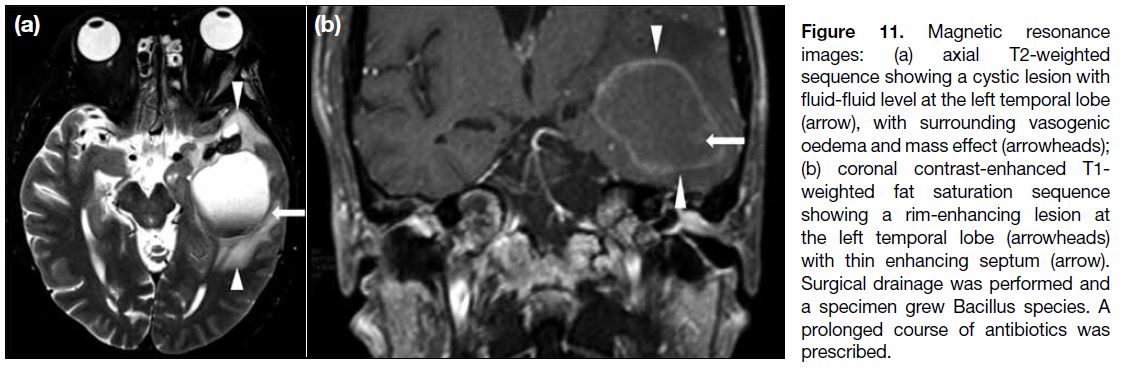

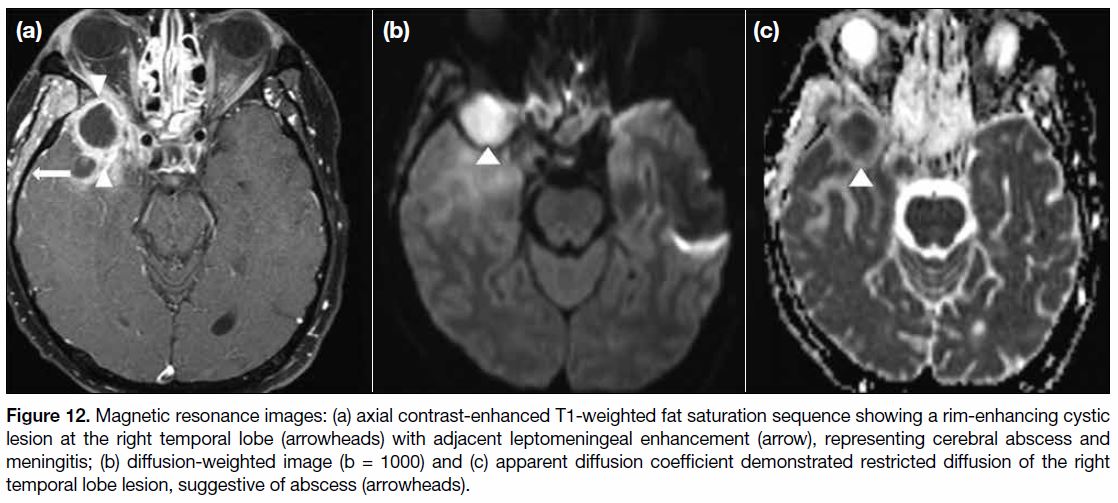

Cerebral Abscess

Cerebral abscess formation may also be encountered,

with postulated ascending infection through bony defects

from radiation-induced osteitis, sinusitis or mastoiditis. Irregular rim enhancement can be seen on MRI (Figure 11). It usually demonstrates less restricted diffusion

(Figure 12).[2]

Figure 11. Magnetic resonance

images: (a) axial T2-weighted sequence showing a cystic lesion with fluid-fluid level at the left temporal lobe (arrow), with surrounding vasogenic oedema and mass effect (arrowheads); (b) coronal contrast-enhanced T1-weighted fat saturation sequence showing a rim-enhancing lesion at the left temporal lobe (arrowheads) with thin enhancing septum (arrow). Surgical drainage was performed and a specimen grew Bacillus species. A prolonged course of antibiotics was prescribed.

Figure 12. Magnetic resonance images: (a) axial contrast-enhanced T1-weighted fat saturation sequence showing a rim-enhancing cystic

lesion at the right temporal lobe (arrowheads) with adjacent leptomeningeal enhancement (arrow), representing cerebral abscess and

meningitis; (b) diffusion-weighted image (b = 1000) and (c) apparent diffusion coefficient demonstrated restricted diffusion of the right

temporal lobe lesion, suggestive of abscess (arrowheads).

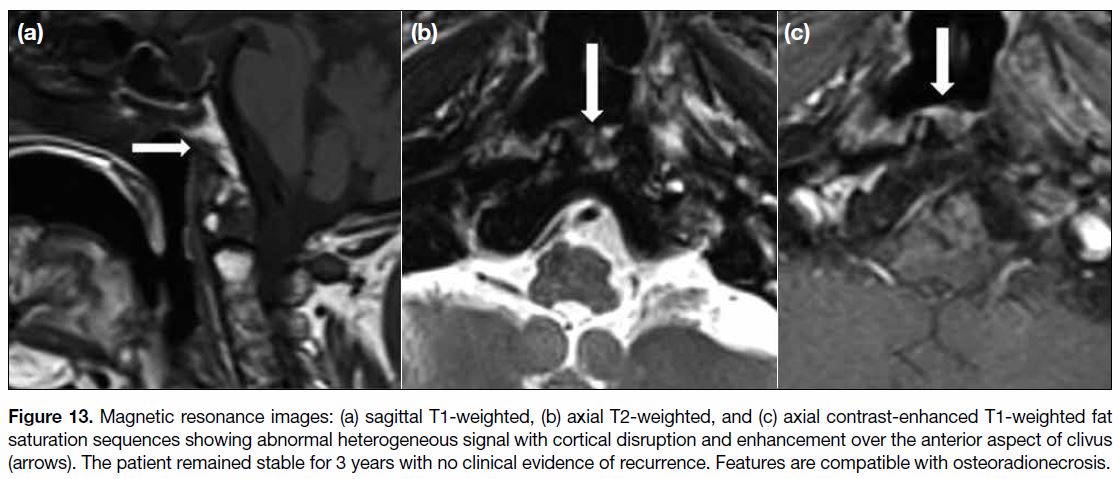

Radiation-induced Osteoradionecrosis

Osteoradionecrosis (ORN) occurs when radiation

fibrosis, bony destruction and vascular injury result in

tissue breakdown, with the risk highest during the first

6 to 12 months following RT.[2] These result in bony

necrosis and sequestration. Computed tomography

detects cortical disruption and loss of marrow

trabeculations while MRI shows heterogeneous T1-weighted low-to-intermediate and T2W intermediate-to-high

marrow signal (Figure 13). Surrounding soft tissue mass may be found and can mimic tumour recurrence

or superimposed osteomyelitis, rendering radiological

diagnosis challenging.[2] A constellation of clinical

findings together with close monitoring and radiological

follow-up are helpful and essential in these cases.

Figure 13. Magnetic resonance images: (a) sagittal T1-weighted, (b) axial T2-weighted, and (c) axial contrast-enhanced T1-weighted fat

saturation sequences showing abnormal heterogeneous signal with cortical disruption and enhancement over the anterior aspect of clivus

(arrows). The patient remained stable for 3 years with no clinical evidence of recurrence. Features are compatible with osteoradionecrosis.

Common sites of ORN include skull base and mandible,

rarely the cervical spine.[11] With disrupted bony cortex

of ORN tissue, microbes can ascend to the cranial fossa

from paranasal sinuses or the otomastoid system with

pneumocephaly. ORN of the mandible can allow spread

of dental infections.

For ORN of the mandible, a staging system based on

the symptoms, clinical and radiographical findings have

been adopted to facilitate patient management. Presence

of bony destruction indicates more advanced disease and need for more aggressive treatment. Dependent on disease

stage, treatment ranges from conservative management

with antibiotics and mouthwashes to hyperbaric oxygen

therapy and ultrasound therapy or surgery.[12]

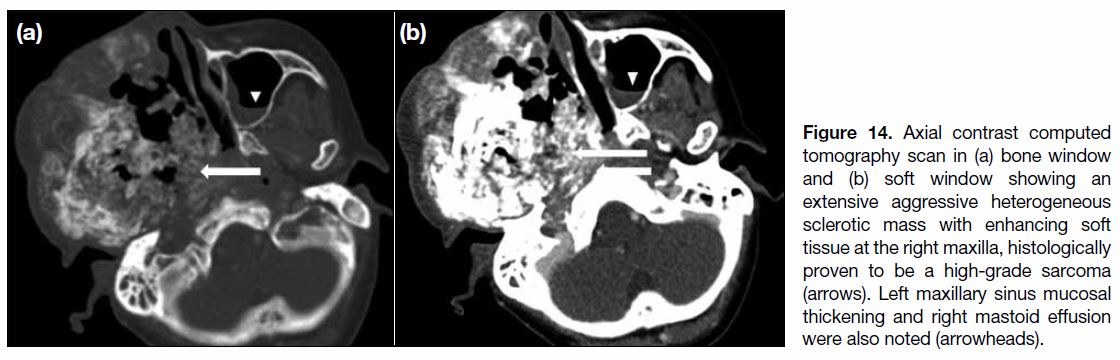

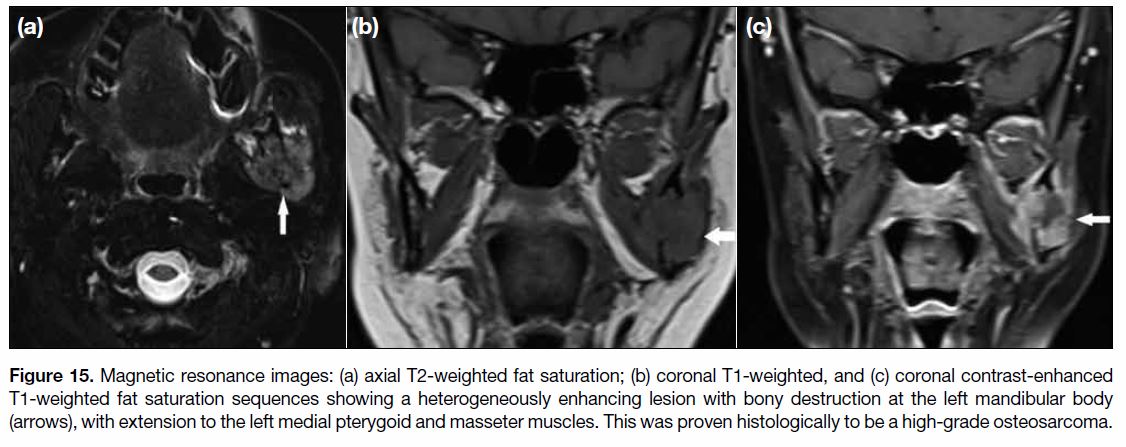

Radiation-induced Neoplasms

To diagnose a radiation-induced neoplasm, one must

occur after a sufficient latency period and histologically

differ to the primary tumour.[1] Radiation-induced

neoplasm is rare. Common histological types are

radiation-induced sarcomas (RIS) and squamous cell

carcinomas (SCC).[13] RIS usually occur 5 to 10 years

after radiation, arising in high-dose field zones such

as the maxilla and skull base.[5] Various histological

subtypes are observed in RIS, including osteosarcoma

and malignant fibrous histiocytoma. Imaging features

can be variable but typically include a rapidly growing

destructive mass with heterogeneous signals, with or

without calcification[2] (Figures 14 and 15).

Figure 14. Axial contrast computed tomography scan in (a) bone window and (b) soft window showing an extensive aggressive heterogeneous sclerotic mass with enhancing soft tissue at the right maxilla, histologically proven to be a high-grade sarcoma (arrows). Left maxillary sinus mucosal thickening and right mastoid effusion were also noted (arrowheads).

Figure 15. Magnetic resonance images: (a) axial T2-weighted fat saturation; (b) coronal T1-weighted, and (c) coronal contrast-enhanced

T1-weighted fat saturation sequences showing a heterogeneously enhancing lesion with bony destruction at the left mandibular body

(arrows), with extension to the left medial pterygoid and masseter muscles. This was proven histologically to be a high-grade osteosarcoma.

SCC typically occur at the temporal bone and external

auditory canals and are seen 10 to 15 years after

irradiation.[3] Like RIS, SCC also carry a poor prognosis[14]

and surgery is the only chance of cure, provided the

tumour is detected at an early stage.

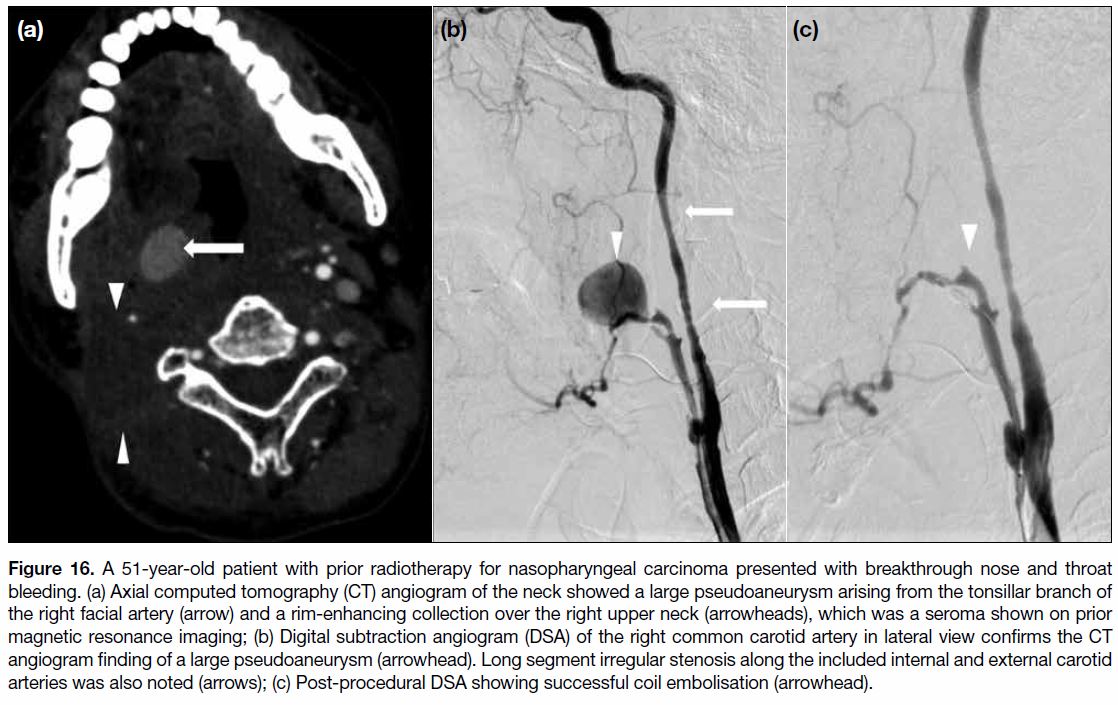

Radiation-induced Vascular Complications

Accelerated atherosclerosis, thrombosis, and intimal

hyperplasia can result in large vessel stenosis and/or

occlusion. Imaging findings may reveal atypically

located, diffuse and less calcified atherosclerosis.[2]

Atherosclerosis can be found at the common carotid

and internal carotid arteries, in addition to the carotid

sinus.

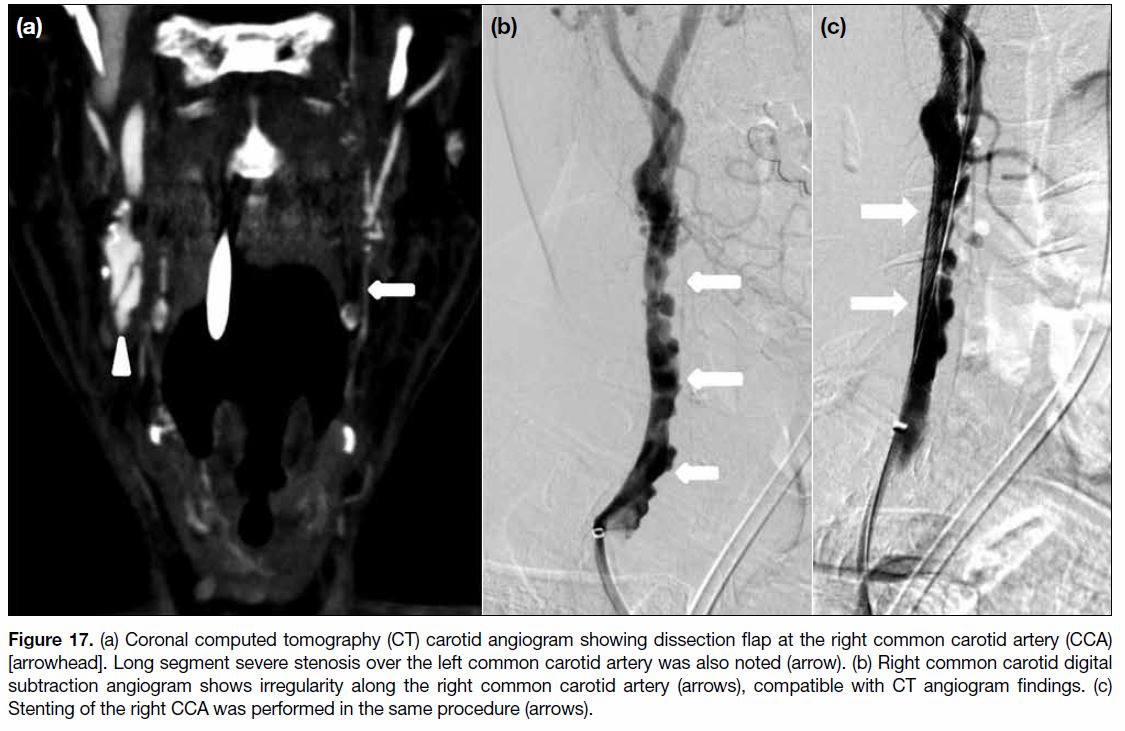

Rare but devastating vascular complications include

pseudoaneurysm formation, (Figure 16) carotid

stenosis or dissection (Figure 17). Therapeutic vascular

intervention may be required and includes stenting for stenosis or dissection and coil embolisation for

pseudoanerysm.[15]

Figure 16. A 51-year-old patient with prior radiotherapy for nasopharyngeal carcinoma presented with breakthrough nose and throat

bleeding. (a) Axial computed tomography (CT) angiogram of the neck showed a large pseudoaneurysm arising from the tonsillar branch of

the right facial artery (arrow) and a rim-enhancing collection over the right upper neck (arrowheads), which was a seroma shown on prior

magnetic resonance imaging; (b) Digital subtraction angiogram (DSA) of the right common carotid artery in lateral view confirms the CT

angiogram finding of a large pseudoaneurysm (arrowhead). Long segment irregular stenosis along the included internal and external carotid

arteries was also noted (arrows); (c) Post-procedural DSA showing successful coil embolisation (arrowhead).

Figure 17. (a) Coronal computed tomography (CT) carotid angiogram showing dissection flap at the right common carotid artery (CCA)

[arrowhead]. Long segment severe stenosis over the left common carotid artery was also noted (arrow). (b) Right common carotid digital

subtraction angiogram shows irregularity along the right common carotid artery (arrows), compatible with CT angiogram findings. (c)

Stenting of the right CCA was performed in the same procedure (arrows).

CONCLUSION

RT, which plays a major role in the treatment of NPC,

can cause a wide spectrum of expected post-procedure changes and complications in the head and neck region.

Familiarisation with the relevant imaging features is

essential in post-irradiation imaging surveillance to

ensure early diagnosis to guide subsequent management.

Imaging features atypical of post-irradiation changes

should raise the suspicion of other pathologies including disease recurrence and radiation-related complications.

REFERENCES

1. Bharatha A, Yu E, Symons SP, Bartlett ES. Early and late-term

effects of radiotherapy in head and neck imaging. Can Assoc radiol

J. 2012;63:119-28. Crossref

2. King AD, Ahuja AT, Yeung DK, Wong JK, Lee YY, Lam WW, et al.

Delayed complications of radiotherapy treatment for nasopharyngeal

carcinoma: imaging findings. Clin Radiol. 2007;62:195-203. Crossref

3. Glastonbury CM, Parker EE, Hoang JK. The postradiation neck:

evaluating response to treatment and recognizing complications.

AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2010;195:W164-71. Crossref

4. Yao JJ, Zhou GQ, Xiao LY, Ling LT, Lei C, Yan PM, et al.

Incidence of and risk factors for mastoiditis after intensity

modulated radiotherapy in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. PLoS ONE.

2015;10:e0131284. Crossref

5. Abdel Razek AA, King A. MRI and CT of nasopharyngeal

carcinoma. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2012;198:11-8. Crossref

6. Chong VF, Fan YF, Mukherji SK. Radiation-induced temporal

lobe changes: CT and MR imaging characteristics. AJR Am J

Roentgenol. 2000;175:431-6. Crossref

7. Chan YL, Leung SF, King AD, Choi PH, Metreweli C. Late

radiation injury to the temporal lobes: morphologic evaluation at

MR imaging. Radiology. 1999;213:800-7. Crossref

8. Cheng KM, Chan CM, Fu YT, Ho LC, Cheung FC, Law CK. Acute

hemorrhage in late radiation necrosis of the temporal lobe: report of

five cases and review of the literature. J Neurooncol. 2001;51:143-

50. Crossref

9. Lin YS, Jen YM, Lin JC. Radiation-related cranial nerve palsy in

patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Cancer. 2002;95:404-9. Crossref

10. Rehman I, Chokshi FH, Khosa F. MR imaging of the brachial

plexus. Clin Neuroradiol. 2014;24:207-16. Crossref

11. King AD, Griffith JF, Abrigo JM, Leung SF, Yau FK, Tse GM,

et al. Osteoradionecrosis of the upper cervical spine: MR imaging

following radiotherapy for nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Eur J Radiol

2010;73:629-35. Crossref

12. Chronopoulos A, Zarra T, Ehrenfeld M, Otto S. Osteoradionecrosis

of the jaws: definition, epidemiology, staging and clinical and

radiological findings. A concise review. Int Dent J. 2018;68:22-30. Crossref

13. Abrigo JM, King AD, Leung SF, Vlantis AC, Wong JK, Tong MC,

et al. MRI of radiation-induced tumors of the head and neck in post-radiation

nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Head Neck. 2009;19:1197. Crossref

14. Chan JY, To VS, Wong ST, Wei WI. Radiation-induced

squamous cell carcinoma of the nasopharynx after radiotherapy

for nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Head Neck. 2014;36:772-5. Crossref

15. Lam JW, Chan JY, Lui WM, Ho WK, Lee R, Tsang RK.

Management of pseudoaneurysms of the internal carotid artery in

postirradiated nasopharyngeal carcinoma patients. Laryngoscope.

2014;124:2292-6. Crossref