At-home Chemotherapy Infusion for Patients with Advanced Cancer in Hong Kong

PERSPECTIVE

At-home Chemotherapy Infusion for Patients with Advanced Cancer in Hong Kong

SSS Mak1, PE Hui1, WMR Wan1, CLP Yih2

1 Department of Clinical Oncology, Prince of Wales Hospital, New Territories East Cluster, Shatin, Hong Kong

2 Department of Surgery, Prince of Wales Hospital, New Territories East Cluster, Shatin, Hong Kong

Correspondence: Dr Ms SSS Mak, Department of Clinical Oncology, Prince of Wales Hospital, New Territories East Cluster, Shatin, Hong Kong. Email: mss692@ha.org.hk

Submitted: 14 Dec 2019; Accepted: 25 Mar 2020.

Contributors: All authors designed the study. SSSM acquired the data. All authors analysed the data analysis, drafted the manuscript, and

critically revised the manuscript for intellectual content. All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final

version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Acjknowledgement: This article is based on a presentation given at the 8th Joint Scientific Meeting of The Royal College of Radiologists & Hong Kong College of Radiologists and 27th Annual Scientific Meeting of Hong Kong College of Radiologists 2019, held in Hong Kong, China.

Funding/Support: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Abstract

This article reviews the development of home-based chemotherapy for patients with advanced cancer in Hong Kong,

highlighting the evolution of chemotherapy infusion devices, practice, and service provision over the past decades.

Further, we provide directions regarding service provision, practice, and training. At-home delivery of chemotherapy

infusions has been used in the treatment of advanced colorectal and pancreatic cancers. It received positive feedback

from patients and had a positive impact on the healthcare system. The model for at-home chemotherapy infusion

could be further promoted and developed in patients with advanced cancer through several means. These could

include exploring the feasibility of more ambulatory home chemotherapy treatment; developing protocols and

selection criteria to guide who should be treated where, how to manage drug toxicity and the expected side-effects,

and assessment of the self-care capabilities of patient and family; and establishing logistics through multidisciplinary

collaboration, chemotherapy nursing clinics, and development of expertise to more efficiently provide resources and

staffing to support at-home chemotherapy infusion. Recognising these challenges, in the future, it would be helpful

to identify new and more advanced practice foci and training initiatives to meet the increased needs of the rising

service load and the population’s need for ongoing access to chemotherapy service.

Key Words: Catheterization, central venous; Chemotherapy, adjuvant / methods; Home infusion therapy; Infusion

pumps; Nurses

中文摘要

香港晚期癌症患者居家化療輸注

麥素珊、許斌、溫偉文、葉春菱

本文回顧在香港為晚期癌症患者提供以居家為基礎的化學治療之發展,強調過去數十年在化療藥物輸注儀器、技術實踐及提供服務的發展。此外,本文描述有關服務、實踐和培訓的發展方向。居家輸注化療的方式已用於治療晚期結直腸癌和胰腺癌,並得到了患者正面的反饋,同時對醫療保健系統產生正面的影響。可通過多種途徑進一步推廣及發展晚期癌症患者居家化療輸注模式。這些途徑包括探究更多流動性居家化學治療的可行性;制定規程及選擇標準以指導誰應該在哪裡進行治療,如何處理藥物毒性及預期副作用,以及評估患者及家庭的自我護理能力;並通過多學科合作、化療護士診所及專門技術構建後勤保障,以更有效地提供資源和人員配備以支援居家化療輸注。認識到這些挑戰將有助於今後確定新的和更先進的實踐目標以及培訓舉措,以滿足正在上升的服務負荷及民眾對持續獲得化療服務不斷增加之需求。

INTRODUCTION

Historically, infusional chemotherapy for patients

with cancer has been delivered in hospitals. Over

the past two decades, chemotherapy practice in

Hong Kong has undergone a shift from inpatient to

outpatient chemotherapy, including delivery of home

chemotherapy. This shift has been partly driven by the

increasing incidence of cancer, with new cases hitting

a record high of 33 075 in 2017[1] and is projected to

increase by around 35% to more than 42 000 new cases

per annum by 2030.[2] Inpatient chemotherapy treatment

may be required for intensive, complex chemotherapy

regimens that can induce severe complications. Such

complications can include bone marrow failure,

prolonged neutropenia, renal toxicity, and tumour lysis

syndrome in bulky tumours. Inpatient treatment may also

be required for unstable disease that imminently requires

chemotherapy or in situations that require hospitalisation

for rigorous monitoring and intervention. However,

most other chemotherapy treatments are implemented

on an outpatient basis, and the proportion of outpatient

treatment is increasing rapidly over time. This has

resulted in an overwhelming demand for oncology

services and hospital beds.

As oncology centres across some clusters are already

delivering chemotherapy services at full capacity, the

increasing demand for services is straining the Hospital

Authority’s service capacity. Future demand for

services is likely to increase further; improving access

to anticancer drugs, improving cancer survival, and an

ageing population are likely to be the key factors causing

this increase. For hospitals without the resources to

appropriately expand their capacity in terms of either

staffing levels or physical space, it is likely that future

patients will face longer waiting lists or reduced service.

Reducing the use of both inpatient beds and ambulatory

day beds for long infusions may help to create capacity

and enhance the cost-effectiveness of the health system.[3] [4]

Home infusion of certain medications such as chemotherapy,[5] opioids,[6] and antibiotics[7] [8] is becoming

a widely used alternative to in-hospital treatment.

Especially in patients with advanced cancer who tend

to be physically fit but receive prolonged chemotherapy,

home chemotherapy provides an opportunity to receive

treatment in the comfort of their homes and the feasibility

to interact much more freely with relatives.

Despite its early use in a few local settings, the development of home chemotherapy infusion is still limited. The 27th

Annual Scientific Meeting of Hong Kong College of

Radiologists 2019 warranted a review of home-based

chemotherapy for patients with advanced cancer in

Hong Kong. The focus of this article is the evolution

of chemotherapy infusion devices, practice, and service

provision in Hong Kong. We aim to present a picture of

the developments in the field and provide directions for

future service provision, practice, and training.

CHEMOTHERAPY INFUSION AT HOME MODEL

There are two commonly cited definitions of

‘chemotherapy at home’. One refers to any type of

administration of chemotherapeutic agents at home (eg,

intravenous, subcutaneous, oral), with or without on-site

supervision by a nurse.[9] The other definition refers to a

service package of chemotherapy-related care provided

by specialist healthcare professionals (usually nurses) at

the patient’s home.[10]

Home chemotherapy can be further categorised as totally

at-home or partially at-home service. For totally at-home

service, the entire process is carried out in the home

setting, for example, short-term infusions delivered at

home by a nurse or injections delivered by parents to

a child with cancer. For partially at-home service, the

first chemotherapy infusion is given in the hospital or

clinic, and later courses or cycles are completed at home

and/or when some hospital or clinic visits are still

required to initiate chemotherapy and disconnect the

infusion pump.

The partially at-home service model is more applicable

for home chemotherapy infusion in Hong Kong because

of the city’s geographical size and the fact that no nurses

currently administer chemotherapy at patients’ homes.

An example of partially at-home service is multi-day

continuous infusion started by a nurse at the hospital,

continued without the nurse’s presence at home, and

finished with disconnection of the pump at the hospital,

which is the common practice of oncology centres in

Hong Kong.

The partially at-home service model is more applicable

for home chemotherapy infusion in Hong Kong because

of the city’s geographical size and the fact that no nurses

currently administer chemotherapy at patients’ homes.

An example of partially at-home service is multi-day

continuous infusion started by a nurse at the hospital,

continued without the nurse’s presence at home, and

finished with disconnection of the pump at the hospital,

which is the common practice of oncology centres in

Hong Kong.

A recent review[5] supported the provision of home-based

chemotherapy as a safe and patient-centred alternative

to hospital and outpatient-based service. Even though

home-based chemotherapy has been proven feasible,

and is facilitated by means of policies in a few countries,

consensus on the best and most cost effective way of

its administration is still lacking.[11] [12] [13] [14] [5] Administration of

chemotherapy in the home setting varies across different

regions of the country, and there is no standard model

that suits all situations. Successful services are tailored to

match local requirements and available resources.

DEVELOPMENT OF HOME

CHEMOTHERAPY INFUSION

SERVICE IN HONG KONG

Early Experience

Implantable long-term venous, epidural, or intrathecal

catheters and electronic ambulatory pumps with

injection ports either totally implanted or tunnelled under

the skin to convenient sites, are commercially available.

Thus, at-home infusion of various medications such as

chemotherapy agents or spinal morphine[6] for patients

with cancer has become feasible. In the 1990s, individual

oncology centres used these devices for continuous

infusion of chemotherapeutic agents via the portal vein

for treatment of colorectal cancer with liver metastases

and for intravenous infusion of the VAD combination

chemotherapy regimen (vincristine, doxorubicin,

dexamethasone) in the treatment of multiple myeloma.

As experience accumulated, the technique was piloted in

Prince of Wales Hospital in 2005 for adjuvant treatment

with a 5-fluorouracil (5FU)–based long-infusion

regimen. A cohort study[16] in 102 patients with colorectal

cancer demonstrated considerable quality-of-life benefits

with ambulatory home infusion via an electronic pump as

compared with inpatient infusion of chemotherapy. That

study also observed reduced treatment delays due to the

lack of inpatient beds, giving cancer patients the option

of receiving chemotherapy at home in Hong Kong.

Promising Benefits and Impact of Current

Service

The use of implantable venous ports and portable infusion

devices in home chemotherapy has become part of the

standard treatment with 5FU-based regimens for various

types of cancer, including colorectal and pancreatic cancer.

These include combination chemotherapy regimens,

such as FOLFOX (folinic acid, 5FU, oxaliplatin) or

FOLFIRI (folinic acid, 5FU, irinotecan), with or without

anti–epidermal growth factor receptor antibodies such

as cetuximab, or panitumumab, or vascular endothelial

growth factor A inhibitor such as bevacizumab.

Both inpatient and outpatient bed days can be saved by

modifying the drug delivery of FOLFOX/FOLFIRI to

occur in the outpatient setting. The 3-hour infusion of

oxaliplatin/irinotecan±cetuximab and 5FU+folinic acid

can be administered in a day centre, followed by a 46-to-

48-hour infusion of 5FU at home using an ambulatory

pump. This obviates the need for hospitalisation and

reducing bed occupancy in day centres, which could

help to reduce hospital workload and related costs.[3] The

number of saved inpatient bed days is at least 2 days per

cycle of FOLFOX/FOLFIRI. This could make a large

impact given the accumulating numbers of patients

requiring this treatment. Increasing day chemotherapy

attendance for home chemotherapy infusion has been

demonstrated with the implementation of the ambulatory

home chemotherapy programme at an oncology centre.[17]

Reduced inpatient and outpatient bed occupancy

enables hospital beds to be reallocated to patients with

a greater need for inpatient care, such as those requiring

more intensive care, palliative care, or chemotherapy

treatments not indicated for home infusion.

Home chemotherapy has been increasingly employed

in oncology centres that have been able to establish

adequate logistics and technical support, and staff

training. A study conducted between 2017 and 2019

involving 24 cancer patients at Pamela Youde Nethersole

Eastern Hospital[18] described the authors’ experience

with home ambulatory chemotherapy using elastomeric

infusion pumps. They concluded that home ambulatory

chemotherapy is safe and effective, that patients enjoy

high levels of satisfaction during treatment, and that such

a valuable service should be promoted more liberally in

hospitals to improve the quality of patient service.

Home Chemotherapy Infusion for Advanced

Cancers

Chemotherapy remains the mainstay treatment for patients with advanced malignancy in developed

countries. Patients with advanced cancer survive longer,

have more treatment options, and adhere to treatment

much longer on new generations of chemotherapy,

targeted therapy, and immunotherapy than they did

before. Home-based oncological care is generally

reserved for end-of-life patients in Hong Kong. Because

management of chemotherapy-related side-effects

has improved and new, safe treatment schedules and

administration tools have been introduced, home-based

chemotherapy is becoming a valid alternative to hospital-based

treatment for patients with advanced cancers.

Additionally, with hospitalisation, patients tend to

participate less in their own care and are less ambulant

because of the lack of spacing, thus disrupting the patients’

normal daily hygiene and exercise routine. Patients with

advanced cancer, who are at particularly high risk for

nosocomial infections[19] and thromboembolism,[20] tend to

benefit tremendously from home-based chemotherapy,

as those conditions are likely to be exacerbated by

hospitalisation. In addition, many patients prefer to

spend time with their families rather than in hospitals.

In 2018, a survey of 22 patients with metastatic

colorectal or pancreatic cancers receiving 5FU-based

home infusion revealed a high level of satisfaction in

the patient group.[17] Two of the patients encountered

minor equipment troubles during one treatment cycle,

which were solved before they left the hospital. None

experienced adverse events during chemotherapy

infusion at home. Moreover, advantages expressed by

the patients and their caregivers included the ability to

continue many daily activities and to participate in their

own care, giving them a greater sense of control over

their treatment.

CORE ELEMENTS OF

IMPLEMENTING AMBULATORY

HOME CHEMOTHERAPY

Multidisciplinary Collaboration

The outpatient and home settings are not necessarily

panaceas for cost savings and efficiency because of

the growing number of toxic treatments and complex

interventions. The emphasis must be on high-quality

multidisciplinary collaboration, especially in high-volume

centres.

Multidisciplinary collaboration is crucial for the provision

of ambulatory home chemotherapy to patients. Smooth

service delivery requires the establishment of protocols and guidelines that provide a well-structured mechanism

with clearly defined workflow involving oncologists,

vascular surgeons, nurses and pharmacists, together with

good communication among team members.

The most common problems during chemotherapy

delivered via peripheral cannulation are thrombophlebitis

and pain. Reliable central venous access is crucial for

patients who need continuous infusion of chemotherapy at

home. To facilitate home chemotherapy, implantation of

a central venous catheter is needed to allow concentrated

drugs to directly enter a central vein and become rapidly

diluted by blood. This protects the peripheral blood

vessel walls from drug irritation, solving the problems of

drug extravasation and pain. Support from other teams

such as vascular surgery or interventional radiology for

placement of central venous access devices (CVADs) is

crucial for this service.

Portable Infusion Devices

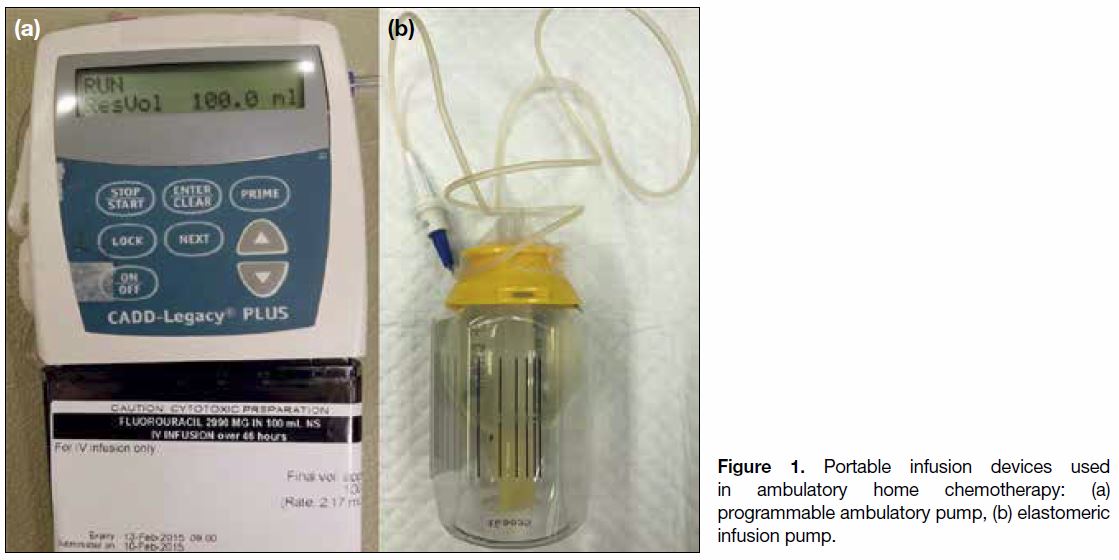

There are two types of portable infusion devices:

programmable infusion pumps (electronic) and

elastomeric infusion pumps (non-electronic) [Figure 1].

Figure 1. Portable infusion devices used in ambulatory home chemotherapy: (a) programmable ambulatory pump, (b) elastomeric infusion pump.

Electronic pumps usually operate via peristaltic

mechanisms that propel the infusion forward via

appendages that move in waves. Decimal rate values are

programmed into the pump to provide either intermittent

or continuous infusions, imparting additional flexibility

to the delivery of various medications and chemotherapy

regimens to treat many diseases and conditions, from

haematological malignancy to chronic pain. These pumps

usually contain audible and visual alarms to alert users

about errors such as occlusion, low battery status, and

pump malfunction. The programming of these pumps

is considered to be one of the procedure’s risks because

of the potential for user error. In addition, electronic

pumps are often sensitive to radiation exposure and can

result in pump malfunction for patients on concurrent

chemoirradiation therapy.[21]

Elastomeric pumps have no buttons for programming

and rely on an elastomeric membrane to generate

pressure that moves the fluid out of the membrane. The

single rate of infusion is controlled by an inline orifice

or flow restrictor. These pumps have benefits over the

electronic ones, such as minimised risks related to pump

programming, lack of noise, lightweight design, and

simplified use. However, the lack of an alarm system can

be risky. Besides, the accuracy of the infusion time can

fluctuate greatly because of factors like temperature and viscosity: one study[22] showed that 40% of elastomeric

pumps had excess solution left upon disconnection.

Neither type of pump is absolutely free of risk nor

universally fit across different regimens. Important factors

for the decision of pump type include the complexity of

chemotherapy, patients’ pump troubleshooting ability,

and the pump’s weight, availability, and cost.

Chemotherapy Nurse Training and Practice

Review

Chemotherapy nurses[23] are usually the staff members

who assess and ensure venous access and deliver

chemotherapy to patients. Appropriate pretreatment

assessment, patient education, and infusion monitoring

are critical to patients on chemotherapy. Their

duties include handling the portable infusion device,

manipulating the CVAD, troubleshooting, emergency

management, and the removal of chemotherapy

materials. Although chemotherapy nurses handle the

bulk of patient care, they also need to ensure that patients

always adhere to care and safety policies. To ensure the

smooth operation of the ambulatory home chemotherapy

service, the relevant extra training, audits, practice

review, and updates on related issues are indispensable.

Patient and Caregiver Counselling and

Education

Chemotherapy nurses are not typically present at the patient’s home throughout the infusion. To enable

patients and their caregivers to better cope with

home chemotherapy administration, assessment and

counselling are provided at the chemotherapy nurse

clinic. Topics include management of treatment-induced

side-effects and symptoms, at-home care of

the implanted CVAD and ambulatory infusion device,

simple troubleshooting, and management of emergencies

such as drug spillage or disconnection of the tubes. The

nurses also provide patients with a list of ‘do’s and don’ts’

to follow while on home chemotherapy.

The major concern raised by patients and their caregivers

has been the availability of support and consultation to

help them when they encounter problems during at-home

chemotherapy administration. Patients and caregivers

should be educated about when to call, the total dose they

are receiving, how long the infusion should last, the need

to occasionally check the remaining drug volume in the

pump, how to protect their devices while showering, and

where to position the pump and catheter while sleeping.

Importantly, a dedicated number is provided for patients

to call in case of emergencies, and a nurse from a day

centre or ward will respond anytime, even during non-office

hours, to address any enquiries about the pump.

Selection of Patient and Vascular Access

Device

Many patients receiving chemotherapy regimens involving 5FU may be eligible for home infusion

therapy. The patients or their caregivers need to have

sufficient mental and cognitive fitness and demonstrable

self-care capabilities. There is no financial means

assessment. Home chemotherapy is generally not

advisable for patients who have poor cognitive function,

learning problems, poor/unstable living environments,

or no telephone access. Elderly patients living alone are

eligible as long as they meet the aforementioned criteria

and have access to phone calls in case of emergencies.

Several factors can guide the selection of the most

appropriate CVAD for each clinical situation. If frequent

blood taking is required, a double-lumen catheter is

more appropriate. The Hickman catheter is preferred for

haematology-oncology patients. If patients require stem

cell apheresis, catheters with a wider lumen are needed.

The implantable port (Figure 2) is inserted completely

under the skin. Hence, it allows patients to carry out

normal daily activities, such as showering, more

conveniently, although it requires surgical insertion and

stitching of the incision wound. The peripherally inserted

central catheter (PICC) has the advantage that insertion

can be performed at the patient’s bedside, which provides

greater flexibility in scheduling. The PICCS are designed

to be used up to 12 months, and most PICCs may stay in

place and in use for several months.

Figure 2. Implantable port must be accessed with a non-coring needle for infusion therapy.

Patients who are prescribed chemotherapy using the

home infusion model are sent to a chemotherapy nurse

clinic for pre-chemotherapy assessment and counselling.

During pre-chemotherapy assessment at the nurse clinic,

patients are assessed on whether they understand and are

suitable for home chemotherapy.

CHALLENGES TO OVERCOME AND

MOVING FORWARD

Availability of Additional Chemotherapy

Regimens for Home Infusion Delivery

Because of the positive feedback received from patients

and the positive impact on the healthcare system of the

chemotherapy infusion at home model, the feasibility

of including more drug regimens for ambulatory

home infusion could be explored. There are other

chemotherapy agents currently under investigation for

home infusion.[15] [24]

Under the partially at-home service model, agents that are

administered over one to several days, with long stability[25]

and manageable toxicities are targeted. The most widely

used agent is 5FU, as the typical treatment runs over 46 hours or continuously with the patient’s radiation

therapy. There is room for extending 5FU home infusion

to various other disease groups in addition to colorectal

and pancreatic cancers by modifying the drug delivery

procedures of inpatient infusion regimens. One possible

example is 4-day carboplatin-5FU for gastric cancer with

the 1-hour infusion of carboplatin administered in a day

centre, followed by a 48-hour at-home infusion of 5FU,

after which patients return to the day centre to resupply

the pump for another 48-hour infusion. Another option

is 5-day cisplatin-5FU for head and neck cancer, with

the first-day regimen including 3-hour inpatient cisplatin

infusion and rigorous hydration with mannitol, followed

by a 48-hour at-home infusion of 5FU, and then repetition

of the 48-hour infusion. Trabectedin[26] is an antineoplastic

agent that could potentially be switched from inpatient to

home administration because its administration requires

prolonged infusion over 24 hours. It has relatively low

toxicity despite the fact that it is a vesicant, and the

possibility of extravasation occurring at home has been

largely prevented by CVAD pre-insertion.

Other advances have led to the development of

further generations of multiple-channel and flexibly

programmable pumps that can deliver temporally

precise patterns of chemotherapy.[27] Such pumps could allow complex chemotherapy regimens to be

switched from the inpatient to the outpatient setting.

Certain patients, especially those with support at

home, can take home several doses of chemotherapy

to be delivered by a programmable digital pump via a

central line and then return for refills. In Europe, this

change in the management of complex treatments has

reduced the number of in-hospital days.[28] Examples

of patients who can benefit from this change include

those with acute leukaemia who receive induction, re-induction,

and consolidation chemotherapy infusions

and patients with lymphoma who are conditioned with

the BEAM regimen (carmustine [BCNU], etoposide,

cytarabine and melphalan) prior to haematopoietic

stem cell transplantation. Other initiatives could also be

undertaken to encourage at-home administration of such

treatments as pump-administered antibiotics. These facts

and products have resulted in the rapid growth of a new

home-care industry.

The possibility of chemotherapy infusion at home

could be increased by calling for extra community care.

Options for improvements include provision of at-home

chemotherapy by a chemotherapy homecare nurse or

community nurse after receiving training, at community

centres, or in a mobile bus for chemotherapy care.[29] Once

the appropriate infrastructure is available, the totally at-home

model that is already popular for chemotherapy

delivery in rural areas of some Western countries (eg,

the United Kingdom, Canada) can be more widely

implemented in Hong Kong. More chemotherapy drugs

with relatively few toxicities and manageable sideeffects

could be included for administration at home or

community centres by chemotherapy nurses regardless

of infusion duration.[9]

Availability of Vascular Access Devices

Throughout the management of at-home chemotherapy

infusion, CVADs have a paramount role. The lack

of a dedicated support team to provide reliable and

adequate vascular access may be one of the reasons

why some hospitals do not offer home chemotherapy.

Besides vascular surgeons, other specialties could

also be involved in performing CVAD placement, for

example, interventional radiologists could perform PICC

insertion, and general surgeons could place implantable

ports. However, the specialties of general surgery and

radiology also face increased pressure due to elevated

demand for their services.

In many Western countries, mainland China, and Taiwan, PICC insertion is commonly done by a properly trained

nurse or PICC nurse in the day centre setting, which

can free physicians for other clinical tasks while still

maintaining quality service.[30] Compared with the other

CVAD types, insertion of a PICC is less invasive and

relatively easy to perform, mainly requiring expertise in

handling needles and guide wires and inserting catheters,

which can be imparted through supervised training.[31]

Strengthening Home Backup Support

The centres that have implemented ambulatory

home chemotherapy service in Hong Kong have not

encountered major problems so far, as the centres

continuously review and share their practices and have

taken measures to prevent potential issues. In the future,

to further expand services to more agents or regimens with

wider toxicity coverage, more intensive and structured

telephone follow-up with patients and their families is

required. Accordingly, patients are always encouraged

to get in touch over the phone if they have problems.

Further, telehealth interventions for remote monitoring

and management of chemotherapy side-effects may help

providers to connect with patients at home.[32] Moreover,

such interventions could help primary healthcare

professionals or community/home care nurses with

chemotherapy training to take on additional roles such

as monitoring, supervising therapy, or home care support.

CONCLUSION

Modern chemotherapy using the ambulatory home

infusion model became widely accepted with the

development of CVADs and portable infusion

devices. Providing sustainable service and staffing

for ambulatory home chemotherapy requires several

components. Protocol development, patient counselling,

and emergency support are necessary. Such support

should account for drug toxicity, the treatment’s

expected side-effects, and the self-care capabilities of

the patient and family. Logistics should be established

through multidisciplinary collaboration, chemotherapy

nurse clinics, expertise development, and training. The

chemotherapy infusion at home model for advanced

cancer could be further promoted and developed by

exploring at-home chemotherapy administration of

additional drugs, identifying future opportunities for work

with newer and more advanced practice foci, and training

initiatives. Such training could involve CVAD placement

and usage, telehealth system support, programmable

digital pumps for complex chemotherapy regimens, and

chemotherapy administration by chemotherapy nurses at

the patient’s home or community centre. Our future goal is to meet the needs for increasing service load and on-going

chemotherapy access to populations who need it.

REFERENCES

1. Hong Kong Cancer Registry, Hospital Authority, Hong Kong SAR

Government. Overview of Hong Kong Cancer Statistics of 2017.

Available from: https://www3.ha.org.hk/cancereg/pdf/overview/

Summary%20of%20CanStat%202017.pdf. Accessed 13 Feb 2020.

2. Hospital Authority. Hospital Authority Strategic Service

Framework for Cancer Services 2019. Available from: https://www.

ha.org.hk/haho/ho/ap/HACANCERSSF_Eng.pdf. Accessed 6 Jun

2020.

3. Joo EH, Rha SY, Ahn JB, Kang HY. Economic and patient-reported

outcomes of outpatient home-based versus inpatient hospital-based

chemotherapy for patients with colorectal cancer. Support Care

Cancer. 2011;19:971-8. Crossref

4. Corrie PG, Moody AM, Armstrong G, Nolasco S, Lao-Sirieix SH,

Bavister L, et al. Is community treatment best? A randomized trial

comparing delivery of cancer treatment in the hospital, home and

GP surgery. Br J Cancer. 2013;109:1549-55. Crossref

5. Evans JM, Qiu M, MacKinnon M, Green E, Peterson K, Kaizer L.

A multi-method review of home-based chemotherapy. Eur J Cancer

Care (Engl). 2016;25:883-902. Crossref

6. Tsui SL, Ng KF, Chan WS, Chan TY, Lo JR, Yang JC. Cancer pain

management: experience of 702 consecutive cases in a teaching

hospital in Hong Kong. Hong Kong Med J. 1996;2:405-13.

7. Grayson ML, Silvers J, Turnidge J. Home intravenous antibiotic

therapy: a safe and effective alternative to inpatient care. Med J

Aust. 1995;162:249-53. Crossref

8. Hitchcock J, Jepson AP, Main J, Wickens HJ. Establishment of an

outpatient and home parenteral antimicrobial therapy service at a

London teaching hospital: a case series. J Antimicrob Chemother.

2009;64:630-4. Crossref

9. Boothroyd L, Lehoux P. Home-based chemotherapy for cancer:

issues for patients, caregivers and the health care system.

Montreal QC: Agence d’Evaluation des Technologies et des

Modes d’Intervention en Sante (AETMIS); 2004. Available

from: https://www.inesss.qc.ca/fileadmin/doc/AETMIS/Rapports/

Cancer/2004_02_en.pdf. Accessed 11 Feb 2020.

10. Young AM, Kerr DJ. Home delivery: chemotherapy and pizza?

BMJ. 2001;322:809-10. Crossref

11. Corbett M, Heirs M, Rose M, Smith A, Stirk L, Richardson G, et al.

The delivery of chemotherapy at home: an evidence synthesis.

Southampton (UK): NIHR Journals Library; 2015. Crossref

12. Anderson H, Addington-Hall JM, Peake MD, MKendrik J, Keane K,

Thatcher N. Domiciliary chemotherapy with gemcitabine is safe and

acceptable to advanced non-small-cell lung cancer patients: results

of a feasibility study. Br J Cancer. 2003;89:2190-6. Crossref

13. Polinski JM, Kowal MK, Gagnon M, Brennan TA, Shrank WH.

Home infusion: safe, clinically effective, patient preferred, and cost

saving. Healthc (Amst). 2017;5:68-80. Crossref

14. Haute Autorité de santé. Conditions du développement de la

chimiothérapie en hospitalisation à domicile: analyse économique

et organisationnelle, Haute Autorité de Santé. mise en ligne janvier

2015 [in French]. Available from: https://www.has-sante.fr/upload/

docs/application/pdf/2015-03/conditions_du_developpement_de_

la_chimiotherapie_en_hospitalisation_a_domicile_-_rapport.pdf.

Accessed 13 Feb 2020.

15. Lüthi F, Fucina N, Divorne N, Santos-Eggimann B, Currat-Zweifel C,

Rollier P, et al. Home care — a safe and attractive alternative to inpatient administration of intensive chemotherapies. Support Care

Cancer. 2012;20:575-81. Crossref

16. Lee YM, Hung YK, Mo FK, Ho WM. Comparison between

ambulatory infusion mode and inpatient infusion mode from the

perspective of quality of life among colorectal cancer patients

receiving chemotherapy. Int J Nurs Pract. 2010;16:508-16. Crossref

17. Mak S, Yih P. Expert Opinion. Ambulatory home chemotherapy

programme — a success story. MIMS Oncology Hong Kong.

Available from: https://specialty.mims.com/topic/ambulatory-home-chemotherapy-programme-.... Accessed

11 Feb 2020.

18. Lee WM. Safety and acceptance of home ambulatory chemotherapy.

Paper presented at: Hospital Authority Convention 2019; 2019 May

14-15; Hong Kong.

19. Sydnor ER, Perl TM. Hospital epidemiology and infection control

in acute-care settings. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2011;24:141-73. Crossref

20. Eichinger S. Cancer associated thrombosis: Risk factors and

outcomes. Thromb Res. 2016;140 Suppl:S12-7. Crossref

21. Bak K, Gutierrez E, Lockhart E, Sharpe M, Green E, Costa S, et al.

Use of continuous infusion pumps during radiation treatment.

J Oncol Pract. 2013;9:107-11. Crossref

22. Salman D, Biliune J, Kayyali R, Ashton J, Brown P, McCarthy T, et al.

Evaluation of the performance of elastomeric pumps in practice:

are we under-delivering on chemotherapy treatments? Curr Med

Res Opin. 2017;33:2153-9. Crossref

23. Mak SS. Oncology nursing in Hong Kong: milestones over the past

20 years. Asia Pac J Oncol Nurs. 2019;6:10-6. Crossref

24. Lal R, Hillerdal GN, Shah RN, Crosse B, Thompsone J,

Nicolson M, et al. Feasibility of home delivery of pemetrexed in

patients with advanced non-squamous non-small cell lung cancer.

Lung Cancer. 2015;89:154-60. Crossref

25. Benizri F, Bonan B, Ferrio AL, Brandely ML, Castagné V,

Théou-Anton N, et al. Stability of antineoplastic agents in use

for home-based intravenous chemotherapy. Pharm World Sci.

2009;31:1-13. Crossref

26. Schöffski P, Cerbone L, Wolter P, De Wever I, Samson I, Dumez

H, et al. Administration of 24-h intravenous infusions of trabectedin

in ambulatory patients with mesenchymal tumors via disposable

elastomeric pumps: an effective and patient-friendly palliative

treatment option. Onkologie. 2012;35:14-7. Crossref

27. Hrushkesky WJ. Home-based circadian-optimized cancer

chemotherapy. In: Berner B, Dinh SM, editors. Electronically

Controlled Drug Delivery. Florida: CRC Press; 2019. p 9-46. Crossref

28. Fridthjof KS, Kampmann P, Dünweber A, Gørløv JS, Nexø C,

Friis LS, et al. Systematic patient involvement for homebased

outpatient administration of complex chemotherapy in acute

leukemia and lymphoma. Br J Haematol. 2018;181:637-41. Crossref

29. Chu H. Is Hong Kong ready for home chemotherapy? MIMS

Oncology Hong Kong. 13 Dec 2016. Available from: https://today.

mims.com/is-hong-kong-ready-for-home-chemotherapy. Accessed

17 Feb 2020.

30. Walker G, Todd A. Nurse-led PICC insertion: is it cost effective?

Br J Nurs. 2013;22(19 Suppl):S9-15. Crossref

31. Jenkins LC. PICC nurses in practice. Radiology Today Magazine.

2009;10:5.

32. Breen S, Ritchie D, Schofield P, Hsueh YS, Gough K, Santamaria N,

et al. The Patient Remote Intervention and Symptom Management

System (PRISMS) — a Telehealth-mediated intervention enabling

real-time monitoring of chemotherapy side-effects in patients with

haematological malignancies: study protocol for a randomised

controlled trial. Trials. 2015;16:472. Crossref