Prostatic Arterial Embolisation in Men with Benign Prostatic Enlargement and Refractory Retention Considered High-risk Surgical Candidates

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Prostatic Arterial Embolisation in Men with Benign Prostatic Enlargement and Refractory Retention Considered High-risk Surgical Candidates

KC Cheng1, WY Wong2, HC Chan1, KK Leung1, SM Yu1, CS Chan1, HS So1

1 Department of Surgery, United Christian Hospital, Kwun Tong, Hong Kong

2 Department of Radiology, Hong Kong Adventist Hospital, Tsuen Wan, Hong Kong

Correspondence: Dr KC Cheng, Department of Surgery, United Christian Hospital, Kwun Tong, Hong Kong. Email: bryan.ckc@gmail.com

Submitted: 29 Apr 2018; Accepted: 25 Jul 2018.

Contributors: KCC, WYW and SMY designed the study. KCC, HCC and KKL acquired the data. KCC analysed the data and drafted the

manuscript. KCC, WYW, HSS and CSC critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors had full access to the

data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding/Support: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics Approval: This study was approved by the Kowloon Central/Kowloon East Research Ethics Committee (Ref REC (KC/KE)-18-0142/FR-

3).

Abstract

Introduction

Prostatic arterial embolisation (PAE) is increasingly used for treatment of benign prostatic enlargement.

We investigated the use of PAE for patients with refractory urinary retention resistant to alpha blockers, who were

high-risk for conventional transurethral surgery.

Methods

This was a prospective cohort study of American Society of Anesthesiology (ASA) Class 3/4 patients.

Computed tomographic angiography of the pelvis was used to screen for feasibility of PAE. PAE was performed

using a standardised technique with tris-acryl microspheres. The primary outcome was the ability to void within

12 weeks after PAE. Secondary outcomes included complications, change in prostate size, and change in serum

prostate-specific antigen (PSA).

Results

Twenty one men were recruited. Mean (±standard deviation) age was 83±5 years, prostate size was

124± 63.4 mL, and serum PSA level was 18.4±10.5 ng/mL. Fourteen patients (66.7%) were judged to be candidates

for PAE; PAE was performed in 13 patients. Median follow-up was 10 weeks (range, 4-30 weeks). Nine (69.2%)

patients had successful voiding trials with seven of them able to void within 2 weeks after PAE. At 6 months after

PAE, PSA was decreased by 46.7%±20.9% and prostate size was reduced by 58.6%±22.5%. Larger prostate size

was significantly correlated with larger percentage reduction of prostate volume (p = 0.036). One patient developed

haematuria requiring readmission on day 5 after PAE; it resolved spontaneously.

Conclusion

PAE was effective and safe for high-risk patients with benign prostate enlargement and refractory urinary retention.

Key Words: Angiography; Embolization, therapeutic; Haematuria; Prostate-specific antigen; Prostatic hyperplasia;

Tomography, X-ray computed

中文摘要

前列腺栓塞術治療高手術風險尿瀦溜患者

鄭冠中、黃慧妍、陳開澤、梁國堅、余燊明、陳志生、蘇慶成

引言

利用前列腺栓塞術(PAE)治療良性前列腺肥大愈發普及。我們研究使用PAE,治療高手術風險而不適合傳統經尿道手術的尿瀦溜患者。

方法

這是一個前贍性研究,對象是美國麻醉學會分級為3或4病人。經過盆腔電腦斷層血管掃瞄證實PAE技術可行後,病人會接受以微球進行的血管栓塞術。首要結果是量度術後十二週內自行排尿的成功率。次要結果是量度術後的併發症,前列腺體積及血清前列腺抗原(PSA)的改變。

結果

共有21位病人參與研究。平均年齡(標準差)為83 ± 5歲,前列腺體積為124 ± 63.4 mL,PSA為18.4 ± 10.5 ng/mL。14位病人(66.7%)經掃描評估後確認為PAE技術上可行。最終13位病人接受PAE治療。隨訪中位數為10周(範圍,4-30周)。9位病人(69.2%)術後成功排尿,其中 7位術後2周已能排尿。術後6個月,PSA下降46.7% ± 20.9%,前列腺體積縮減了58.6% ± 22.5%。體積較

大的腺體術後縮減較多(p = 0.036)。一位病人術後5天出現血尿須住院觀察,其後血尿自行消退。

結論

PAE為高手術風險的前列腺肥大併發尿瀦留患者提供有效及安全的治療。

INTRODUCTION

Acute urinary retention is a well-known complication in

the development of benign prostatic enlargement (BPE).[1]

In patients that have failed voiding trials or presented

with obstructive uropathy, transurethral prostate surgery

is the standard treatment. Transurethral prostate surgery,

despite its minimally invasive nature, has associated

morbidities.[2] These are of great concern in patients with

poor general health that puts them at high surgical risk.

Prostatic arterial embolisation (PAE) is an alternative

treatment for BPE, which can result in a significant

reduction in prostate volume, improvement in flow rate

and residual urine volume, and reduction in symptom

score.[3] However, there have been limited publications

on the use of PAE in patients with refractory retention.

We investigated the use of PAE for patients who were

at high surgical risks and had refractory retention, and

studied the post-PAE voiding outcomes.

METHODS

We conducted a prospective single-arm cohort study from

April 2017 to March 2018. All emergency admissions

to urology wards were screened by urologists for study

eligibility. Principles outlined in the Declaration of

Helsinki were followed. Informed consent was obtained,

and factsheets were given to patients. Inclusion and exclusion criteria are shown in Table 1. Refractory

retention was defined as emergency admissions for

acute urinary retention, and failed voiding trials within 2

weeks after given daily doses of alpha blockers. Medical

history was evaluated and an American Society of

Anesthesiologists (ASA) score was assigned to patients.

Prostate size was measured by transrectal ultrasound by

urologists using the ellipsoid formula. Prostate size was

divided into moderate enlargement (≤80 mL) and severe

enlargement (>80 mL) to assess the effect of PAE on

these two groups.

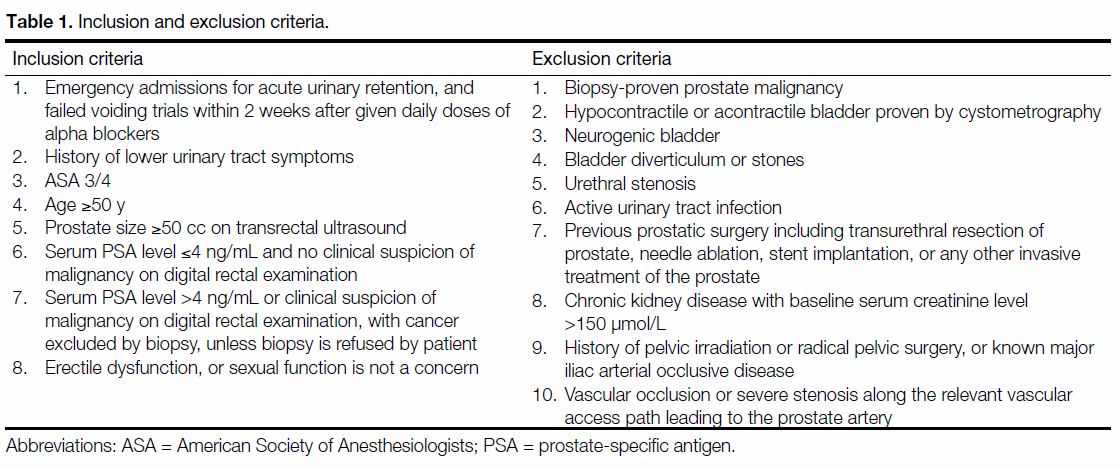

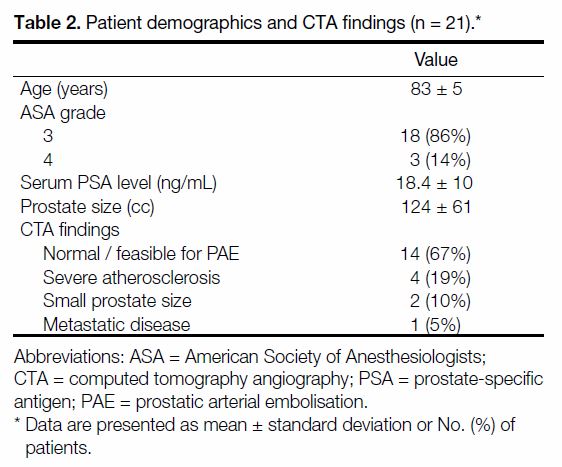

Table 1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Once patients were recruited, alpha-adrenergic blockers

were discontinued. Pre-PAE uroflowmetry was not

possible as patients had indwelling catheters. Computed

tomography angiography (CTA) of the pelvis was

performed with a 64-slice multidetector CT (General

Electric Healthcare, Milwaukee [WI], US) to screen

for vascular abnormalities that might preclude PAE

and to look for any potential variant origins of the

prostatic arteries. An injection of 120 mL of iodinated

contrast (Omnipaque 350; GE Healthcare [Shanghai]

Co., Ltd. Shanghai, China) at 3.5 to 4 mL/s, depending

on the size of the angiocatheter, was administered. A

pre-contrast scan of the pelvis preceded the contrast-enhanced

acquisition. A sublingual vasodilator (0.5 mg

nitroglycerine) was given before imaging of the arterial phase to help identify small arteries. Arterial phase

imaging was then performed with bolus triggering in the

abdominal aorta plus a 10 s delay. Afterwards, the venous

phase was acquired with a mean time of 70 to 80 s from

the time of injection. A designated radiologist with 5

years of endovascular intervention experience reviewed

the CTA images and decided upon the feasibility of

PAE. If there was any doubt about the feasibility, the

first radiologist would seek a second opinion from a

radiologist with 30 years’ experience. Catheterised urine

was saved for culture and indwelling urinary catheters

were not removed until PAE.

PAE was performed as an inpatient procedure with

patients admitted one day prior to the procedure. Baseline

pre-PAE blood tests included serum prostate-specific

antigen (PSA). All antiplatelet and anticoagulation

medications were withheld perioperatively according

to physicians’ advice. Patients fasted for 6 hours before

PAE. Premedication including oral diclofenac extended-release

tablet 100 mg, oral pantoprazole 40 mg, and a

bisacodyl 10 mg suppository, administered on the day

before embolisation. Intravenous levofloxacin 500 mg

was used for antibiotic prophylaxis on-call to the

radiology suite.

PAE was performed with a standardised technique for

all recruited patients. All procedures were performed

by the two interventional radiologists. A Siemens Artis

Zee ceiling-mounted fluoroscopy unit (Siemens Medical

Solutions, Forchheim, Germany) was used for all

procedures. The procedures were performed under local

anaesthesia using 5 mL 1% lidocaine. The right femoral artery was cannulated with a 5-Fr vascular sheath.

Bilateral internal iliac angiograms were performed

using tube rotation at ipsilateral 35° and craniocaudal

angulation at 10°. The choice of angiographic

catheters for internal iliac artery angiograms (4-Fr

Cobra 1, Cordis, Bridgewater [NJ], US; 4-Fr Simmons

Sidewinder 1 Terumo, Inc., Tokyo, Japan; 5-Fr RIM,

Cook, Bloomington [IN], US) depended on the CTA

findings and operators’ preference. In case of difficult

anatomy making cannulation of the right prostatic artery

impossible via a right femoral approach, a left femoral

approach was used.

Using the CTA for reference, the arterial supply to the

prostate was identified and one or both prostatic arteries

were cannulated using a microcatheter (Merit Maestro

2.4 Fr; Merit Medical Systems Inc. South Jordan [UT],

US) with or without the use of a microguidewire. Either

a Tenor steerable guidewire 0.014 in (Merit Medical)

or a Transcend 0.014 in steerable guidewire (Boston

Scientific, Inc., Natick [MA], US) were used. When the

position of a catheter was in doubt, cone beam CT was

used for further delineation.

After successful cannulation of one or both prostatic

arteries, selective angiograms were performed before

embolisation to ensure the position of microcatheter

inside the prostatic artery, to confirm the arterial supply

to that side of the prostate, and to exclude other arterial

supply from the prostatic artery to areas other than the

prostate. Embolisation was performed using tris-acryl

microspheres (Embosphere microspheres, Merit

Medical) of diameter 300 to 500 μm. Nitroglycerine 100 μg was injected intra-arterially before embolisation

to prevent vasospasm, facilitate delivery of particles,

and minimise reflux of particles and non-target

embolisation. In order to avoid non-target embolisation,

the Embosphere particles (2 mL) were suspended in a

22-mL solution (a mixture of 8 mL normal saline and

14 mL Omnipaque 350), which was slowly injected

using a 2-mL syringe under fluoroscopic guidance

until there was contrast stasis in the prostatic artery.

Angiograms were performed after PAE to confirm

obliteration of the prostatic arteries. Technical success

was defined as successful embolisation of one or both

prostatic arteries.

After PAE, patients were kept on complete bed rest for

24 h. Any complications were managed and recorded

according to the Society of Interventional Radiology

Classification System. Diclofenac extended-release

tablets, pantoprazole, and levofloxacin were continued

for 1 week following the procedure. Patients were

discharged with an indwelling urinary catheter.

Outpatient voiding trials were scheduled for 1, 2, 4, and

12 weeks after PAE. Clinical follow-up was arranged

3 months after PAE. Clinical assessment of lower urinary

tract symptoms, uroflowmetry, post-void residual urine

volume, serum PSA, transrectal ultrasound scans, and

validated questionnaires with International Prostate

Symptoms Score and Quality of Life (IPSS/Qol) was

conducted.

Primary outcome measure was successful voiding within

12 weeks after PAE. Successful voiding was defined as

a residual <350 mL and no evidence of painful retention.

Other outcomes included complications of PAE, reduction

in prostate size, and changes in serum PSA level.

Statistical calculations were conducted using SPSS

(Windows version 22.0; IBM Corp, Armonk [NY], US).

Descriptive statistics was used to calculate the primary

and secondary outcomes. Serum PSA levels and prostate

volumes before and after PAE were compared with the

Wilcoxon signed rank test. Correlation between prostate

size and prostate size percentage reduction were tested

with Spearman’s correlation. The Mann-Whitney U

test was performed to test any difference in percentage

reduction in prostate volume between moderately and

severely enlarged glands. Statistical significance was

taken as p < 0.05.

The STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of

Observational Studies in Epidemiology) guidelines were used in reporting of the study results.[4]

RESULTS

Twenty-one men were recruited into the study. The mean

(±standard deviation) age was 83±5 years. Eighteen

patients belonged to ASA class 3 (attributable to chronic

obstructive pulmonary disease [n = 5], congestive heart

failure [n = 3], coronary artery disease [n = 5], and poorly

controlled hypertension [n = 5]). Four patients belonged

to ASA class 4 (attributable to chronic obstructive

pulmonary disease [n = 2] and congestive heart failure

[n = 2]). The mean PSA was 18.4±10.5 ng/mL and

the mean prostate size was 124±63.4 mL. Fourteen

(66.7%) patients were deemed feasible for PAE after

CTA assessment and seven patients were excluded after

CTA (severe atherosclerosis [n = 4], small prostate size

[n = 2], metastatic prostate cancer [n = 1]) [Table 2].

Table 2. Patient demographics and CTA findings (n = 21)

One patient died of pneumonia before PAE. Thirteen

patients proceeded to PAE with 16 total embolisations.

The technical success rate was 100%. Bilateral

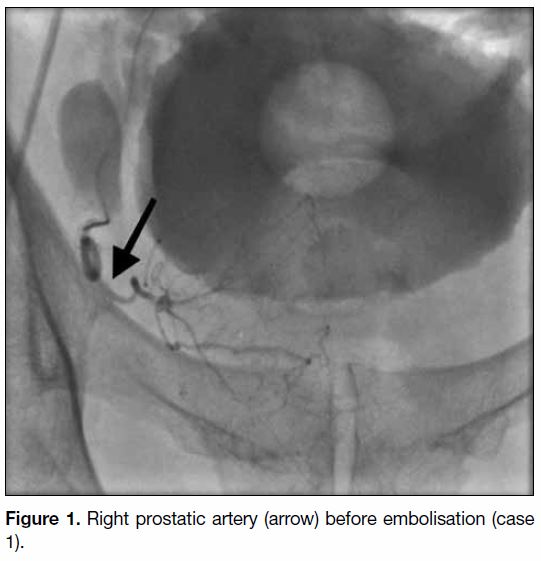

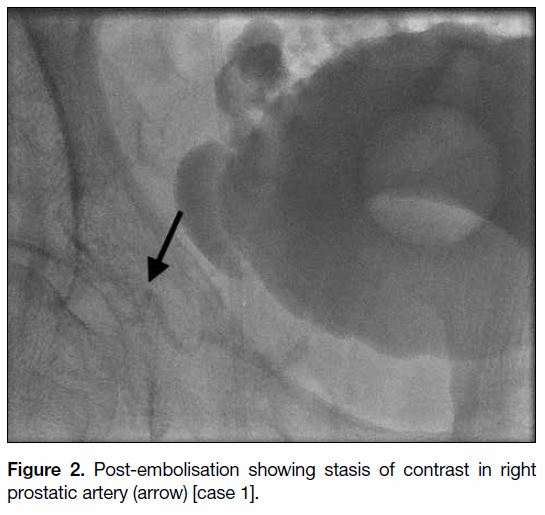

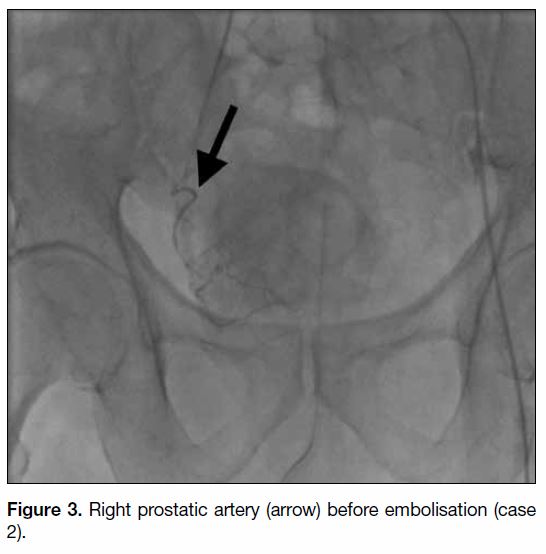

embolisations were successful in nine patients (Figures 1 2 3 4). Three patients had only unilateral embolisation

performed on the first attempt due to prolonged procedure

time reaching the peak dose of contrast. Embolisations of

the contralateral prostatic artery were performed in these

cases 2 months after the first embolisations. One patient

had one-sided PAE performed only, as the preprocedural

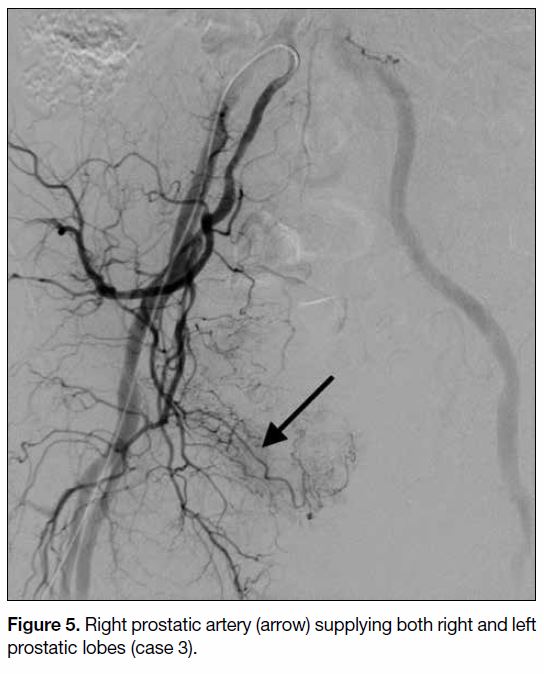

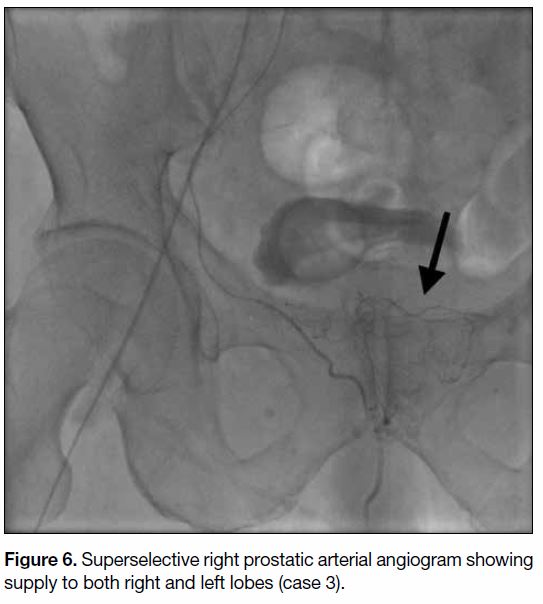

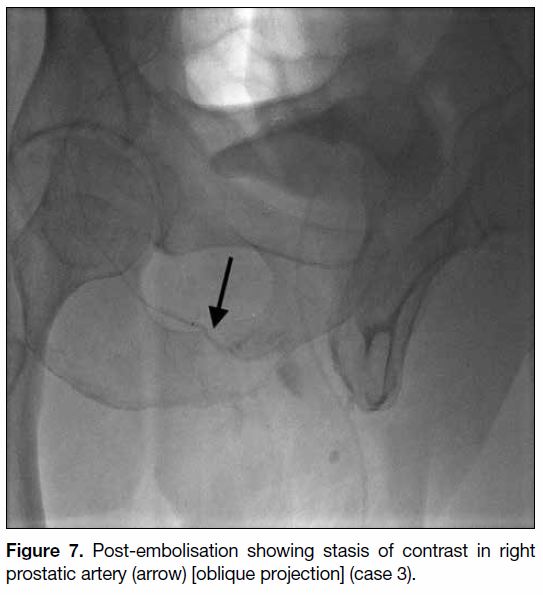

angiogram showed the entire prostate to be supplied

by the right prostatic artery (Figures 5 6 7). The mean

dose area product was 14,489.5 μGy·m2 (range, 5230.2-

24 212.3 μGy·m2). All 13 patients attended follow-up

and were analysed.

Figure 1. Right prostatic artery (arrow) before embolisation (case 1).

Figure 2. Post-embolisation showing stasis of contrast in right prostatic artery (arrow) [case 1].

Figure 3. Right prostatic artery (arrow) before embolisation (case 2).

Figure 4. Post-embolisation showing stasis of contrast in right prostatic artery (arrow) [case 2].

Figure 5. Right prostatic artery (arrow) supplying both right and left prostatic lobes (case 3).

Figure 6. Superselective right prostatic arterial angiogram showing supply to both right and left lobes (case 3).

Figure 7. Post-embolisation showing stasis of contrast in right prostatic artery (arrow) [oblique projection] (case 3).

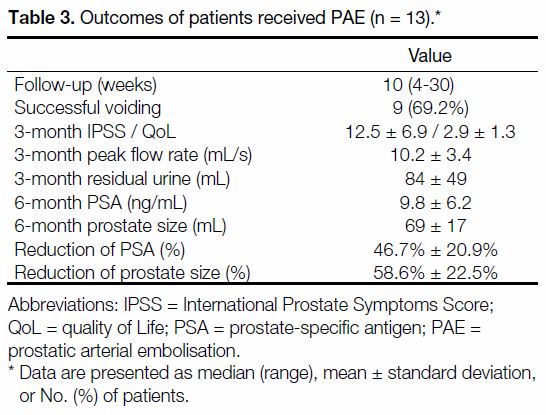

Nine patients (69.2%) had successful voiding trials with

seven of them able to void within 2 weeks after PAE

(Table 3). Despite the poor results of voiding trials, there

were reductions in PSA and prostate size. Serum PSA

levels were decreased by 46.7%±20.9% (p = 0.041) and

prostate size was reduced by 58.6%±22.5% (p = 0.028).

Larger prostate size was significantly correlated with

larger percentage reduction of prostate volume after

PAE (p = 0.036). Prostate volume percentage reduction

was 19.4% for moderately enlarged prostates and 43.6%

for severely enlarged prostates.

Table 3. Outcomes of patients received PAE (n = 13).

One patient developed haematuria requiring readmission

on day 5 after PAE. The haematuria subsided

spontaneously on observation (Society of Interventional

Radiology Classification Class B). No other adverse

events were recorded.

DISCUSSION

Refractory retention in men with evidence of BPE is

one of the indications for transurethral prostate surgery.

When successful, the surgery provides patients with the opportunity to live without an indwelling urinary

catheter. However, some men of advanced age have

co-morbidities, especially cardiorespiratory diseases,

which might preclude surgery. In these cases, long-term

indwelling urinary catheters, intermittent catheterisation,

or prostate stent insertion under local anaesthesia are

possible considerations. Prostate stent insertion is a

self-financed item in our district; thus, men with co-morbidities

and financial constraints would have to deal

with urinary catheters for the rest of their lives.

PAE is increasingly used for treatment of BPE. In the study by Pisco et al,[3] PAE was successful in 97% of

cases with a significant reduction in IPSS/QoL score and

improvement in peak flow rate. Recent meta-analyses[5] [6]

also showed a significant improvement in peak flow

rate and IPSS/QoL scores at 12 months after PAE. The

majority of published studies, however, are small and

single-site studies. The indications were heterogeneous

and few had reported the clinical success of PAE

in patients with co-morbidities.[7] [8] [9] A local study had

reported successful PAE outcomes in weaning catheters

in patients with retention of urine due to BPE.[10] In our

study we utilised PAE for high-surgical-risk patients

with indwelling catheters due to refractory retention.

The ultimate goal was to achieve spontaneous voiding

without exposure to the risk of anaesthesia and surgery.

Our pilot study showed a promising result in these

high-risk patients. The technical success rate was 100%,

although in some cases only unilateral embolisations

were possible in the first session. Conventional

angiograms had already confirmed the position of the

microcatheter and of the prostate arterial supply; thus,

cone beam CT was avoided in most cases. Nearly 70%

of patients in our cohort had successful voiding trials

after PAE, with the majority of them able to void within

2 weeks after PAE. This fast-acting clinical success of

PAE was accompanied by substantial early reduction

in prostate volume at 1 month after PAE and sustained

reduction 6 months after PAE (Figure 1). Serum PSA

levels also reduced substantially.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first local

study to report PAE outcomes in men with refractory

retention and high surgical or anaesthetic risks. Yu et al[10]

had reported the excellent local results of PAE in

patients with complete urinary outflow obstruction.

Their group reported a higher success rate of voiding

trials (87.5% vs. 69.2%) than ours. The difference

could be explained by the younger mean age (66 vs.

83 years) and smaller prostate size (77 [study group]/

65.6 [control group] vs. 124 mL) in their cohort. The

chance of underactive bladder increased when patients

are older or when there is prolonged bladder outlet

obstruction.[11] Our lower rate of clinical success could be

related to the poorer bladder function in our older group

of patients with larger prostates. To address this issue, we

could investigate all cases with cystometrography before

and after PAE in future. Their study, however, did not

show any data on the anaesthetic risks and co-morbidities.

Our early results could potentially broaden the utilisation

of PAE in patients with high cardiorespiratory risks. More studies are needed to establish the role of PAE in

these high-risk patients and to validate our results.

The 80 mL was used in our study as a cut-off to

differentiate moderately and severely enlarged prostate

glands. This is based on the European Association

of Urology guidelines, which recommend different

treatment options for glands using the 80 mL cut-off.[12]

Conventional transurethral prostatectomy was not

recommended for prostates >80 mL, as it was considered

ineffective to resect such a large gland and possessed high

surgical risk. Instead, techniques such as holmium laser

enucleation of prostate or more invasive techniques, such

as open enucleation, were recommended.[12] However, the

clinical success of PAE had been shown to be independent

of the prostate size and even had better result in larger

prostate glands. Kurbatov et al[13] reported the efficacy

and safety of PAE for prostate volumes >80 mL. Wang

et al[14] had compared the PAE results of different prostate

sizes with cut-off of 80 mL. They found the improvement

in IPSS/QoL, peak flow rate, post-void residual, and

prostate volume reduction were all significantly better in

prostate sizes >80 mL.[14] These agree with our findings,

which showed the prostate volume reduction was much

greater in larger prostates. The reason is still uncertain.

It was hypothesised that the hypervascularity and larger

prostate size in large glands might facilitate embolisation

and result in a larger volume of infarction.[14] It makes

PAE even more appealing to those high-surgical-risk

patients with large prostates, as they could avoid more

invasive procedures such as open enucleation.

PAE was in general well tolerated and the majority

of studies reported few minor complications.[3] [5]] [10]

Commonly reported complications were urinary tract

infections (2%-19%), transient haematuria (10%),

transient haemospermia (7%), inguinal haematoma

(7%), urinary retention (8%-26%), and pelvic pain

(2%-9%).[3] [5] [15] In our cohort, only one patient had

haematuria requiring readmission, which resolved

spontaneously.

Our results were limited by the single-centre design with

small sample size. Moreover, approximately one-third

of patients were excluded owing to unfavourable

vascular anatomy or diffuse atherosclerotic disease.

These exclusions were higher than previously reported

(inclusion rate, 89.9%-100%).[3] [10] [15] Compared with other

studies, our patients were much older, with multiple

co-morbidities. After considering technical factors and

anatomical difficulties, more patients were inevitably excluded due to poor vascular status. Three patients had

unilateral PAE performed only in the first embolisation

attempt. These could be explained by the learning

curve of radiologists, as all these cases were done in

the early phase of the study. With more experiences in

catheterisation of the prostatic artery and in interpreting

the CTA, bilateral embolisations were achievable in

single session in later cases. Due to limited resources,

magnetic resonance imaging was not performed to assess

the percentage of prostate infarction. We were also unable

to show the changes in urodynamics and IPSS/QoL

results as all patients were on indwelling catheters before

PAE.

CONCLUSION

PAE was an efficacious and safe option for high-surgical-risk patients with benign prostate enlargement in

refractory retention. With this encouraging preliminary

result, we could further develop and establish the role of

PAE among the different treatment modalities for BPE

in our centre.

REFERENCES

1. Jacobsen SJ, Jacobson DJ, Girman CJ, Roberts RO, Rhodes T,

Guess HA, et al. Treatment for benign prostatic hyperplasia among

community dwelling men: the Olmsted County study of urinary

symptoms and health status. J Urol. 1999;162:1301-6. Crossref

2. Cornu JN, Ahyai S, Bachmann A, de la Rosette J, Giling P, Gratzke C,

et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of functional outcomes

and complications following transurethral procedures for lower

urinary tract symptoms resulting from benign prostatic obstruction:

an update. Eur Urol. 2015;67:1066-96. Crossref

3. Pisco J, Campos Pinheiro L, Bilhim T, Duarte M, Rio Tinto H,

Fernandes L, et al. Prostatic arterial embolization for benign

prostatic hyperplasia: short- and intermediate-term results.

Radiology. 2013;266:668-77. Crossref

4. von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC,

Vandenbroucke JP; STROBE Initiative. The Strengthening the

Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. J Clin

Epidemiol. 2008;61:344-9. Crossref

5. Uflacker A, Haskal ZJ, Bilhim T, Patrie J, Huber T, Pisco JM.

Meta-analysis of prostatic artery embolization for benign prostatic

hyperplasia. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2016;27:1686-97.e8. Crossref

6. Wang XY, Zong HT, Zhang Y. Efficacy and safety of prostate artery

embolization on lower urinary tract symptoms related to benign

prostatic hyperplasia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin

Interv Aging. 2016;11:1609-22. Crossref

7. Bhatia S, Sinha VK, Kava BR, Gomez C, Harward S, Punnen S, et al.

Efficacy of prostatic artery embolization for catheter-dependent

patients with large prostate sizes and high comorbidity scores. J

Vasc Interv Radiol. 2018;29:78-84.e1. Crossref

8. Gabr AH, Gabr MF, Elmohamady BN, Ahmed AF. Prostatic artery

embolization: a promising technique in the treatment of high-risk

patients with benign prostatic hyperplasia. Urol Int. 2016;97:320-4. Crossref

9. Yan WH, Zhang C, Al GP, Shu Y. Prostatic arterial embolization for

benign prostatic hyperplasia in high-risk aged males [in Chinese].

Zhonghua Nan Ke Xue. 2015;21:900-3.

10. Yu SC, Cho CC, Hung EH, Chiu PK, Yee CH, Ng CF. Prostate

artery embolization for complete urinary outflow obstruction due

to benign prostatic hypertrophy. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol.

2017;40:33-40. Crossref

11. Osman NI, Chapple CR, Abrams P, Dmochowski R, Haab F, Nitti V,

et al. Detrusor underactivity and the underactive bladder: a new

clinical entity? A review of current terminology, definitions,

epidemiology, aetiology, and diagnosis. Eur Urol. 2014;65:389-98. Crossref

12. Gratzke C, Bachmann A, Descazeaud A, Drake MJ, Madersbacher

S, Mamoulakis C, et al. EAU guidelines on the assessment of nonneurogenic

male lower urinary tract symptoms including benign

prostatic obstruction. Eur Urol. 2015;67:1099-109. Crossref

13. Kurbatov D, Russo GI, Lepetukhin A, Dubsky S, Sitkin I, Morgia G,

et al. Prostatic artery embolization for prostate volume greater than

80 cm3: results from a single-center prospective study. Urology.

2014;84:400-4. Crossref

14. Wang M, Guo L, Duan F, Yuan K, Zhang G, Li K, et al. Prostatic

arterial embolization for the treatment of lower urinary tract

symptoms caused by benign prostatic hyperplasia: a comparative

study of medium- and large-volume prostates. BJU Int.

2016;117:155-64. Crossref

15. Gao YA, Huang Y, Zhang R, Yang YD, Zhang Q, Hou M, et al.

Benign prostatic hyperplasia: prostatic arterial embolization versus

transurethral resection of the prostate — a prospective, randomized,

and controlled clinical trial. Radiology. 2014;270:920-8. Crossref